Sedentism

In cultural anthropology, sedentism (sometimes called sedentariness) simply refers to the practice of living in one place for a long time. The majority of people belong to sedentary cultures. In evolutionary anthropology and archaeology, it takes on a slightly different sub-meaning and is often applied to the transition from nomadic society to a lifestyle that remains in one place permanently. Essentially, sedentism means living in groups permanently in one place.[1]

Initial requirements for permanent, non-agricultural settlements

For small-scale nomadic societies it can be difficult to adopt a sedentary lifestyle in a landscape without on-site agricultural or livestock-breeding resources, since sedentism often requires sufficient year-round, easily accessible local natural resources.

Non-agricultural sedentism requires good preservation and storage technologies, such as smoking, drying, and fermentation, as well as good containers such as pottery, baskets, or special pits in which to securely store food whilst making it available. It was only in locations where the resources of several major ecosystems overlapped that the earliest non-agricultural sedentism occurred. For example, people settled where a river met the sea, at lagoon environments along the coast, at river confluences, or where flat savanna met hills, and mountains with rivers.

Before agriculture

In the last 30 years archaeological research has shown the earliest sedentism began with on-site agriculture and cattle breeding, and most researchers now believe that sedentism was a prerequisite for the first agriculture to occur. Sedentism usually meant more people, sturdier houses, new stone tools, more jewelry, burials or cemeteries, more long-distance goods and also clear signs of social stratification. At sedentary sites usually more people lived together for a longer time compared to earlier base camp sites or annual gathering sites. This created deeper cultural layers and thus generally richer archaeological materials. There are also indications that the use of rock art is connected to sedentism, both pre-agricultural and agricultural forms.

Criteria for the recognition of sedentism in archaeological studies

In archaeology a number of criteria is necessary for the recognition of either semi or full sedentism.

According to Israeli archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef, they are as follows:

1. Increasing presence of organisms that benefit from human sedentary activities, e.g.

- House mice

- Rats

- Sparrows

2. Cementum increments on mammal teeth

- Indications that hunting took place in both winter and summer

3. Energy expenditure

- Leveling slopes

- Building houses

- Production of plaster

- Transport of undressed stones

- Digging of graves

- Shaping of large mortars[2]

Historical regions of sedentary settlements

A year-round sedentary site, with its larger population, generates a substantial demand on local naturally occurring resources, a demand that may have triggered the development of deliberate agriculture. In the Middle East the Natufian culture was the first to become sedentary at around 12000 BC. The Natufians were sedentary for more than 2000 years before they, at some sites, started to cultivate plants around 10000 BC. However, the first sedentary sites were pre-agricultural, and they appeared during the Upper Paleolithic in Moravia in Europe and on the East European Plain during the interval of c. 25000-17000 BC.[3]

The Jōmon culture in Japan, which was primarily a coastal culture, was sedentary from c. 12000 to 10000 BC until the cultivation of rice at some sites in northern Kyushu.[4][5] In northernmost Scandinavia, there are several early sedentary sites without evidence of agriculture or cattle breeding. They appeared from c. 5300-4500 BC and are all located optimally in the landscape for extraction of major ecosystem resources.[6] In Sweden, the Lillberget Stone Age village site (c. 3900 BC) represents such a site, as do the Nyelv site (c. 5300 BC) in Norway, and the lake Inari site (c. 4500 BC) in Finland.[7] In northern Sweden the earliest indication of agriculture occurs at previously sedentary sites, and one example is the Bjurselet site used during the period c. 2700-1700 BC, famous for its large caches of long distance traded flint axes from Denmark and southernmost Sweden (some 1300 km). The evidence of small-scale agriculture at that site can be seen from c. 2300 BC (burnt cereals of barley).

Historical effects of increased sedentism

Sedentism increased contacts and trade, and the first Middle East cereals and cattle in Europe, could have spread through a stepping stone process, where the productive gift (cereals, cattle, sheep and goats) were exchanged through a network of large pre-agricultural sedentary sites, rather than a wave of advance spread of people with agricultural economy, and where the smaller sites found in between the bigger sedentary ones, did not get any of the new products. Not all contemporary sites during a certain period (after the first sedentism occurred at one site) were sedentary. Evaluation of habitational sites in northern Sweden indicates that less than 10 percent of all the sites around 4000 BC, were sedentary. At the same time, only 0.5-1 percent of these represented villages with more than 3-4 houses. This means that the old nomadic or migratory life style continued in a parallel fashion for several thousand years, until somewhat more sites turned to sedentism, and gradually switched over to agricultural sedentism.

The shift to sedentism is coupled with the adoption of new subsistence strategies, specifically from foraging (hunter-gatherer) to agricultural and animal domestication. The development of sedentism led to the rise of population aggregation and formation of villages, cities, and other community types.

In North America, evidence for sedentism emerges around 4500 BC.

Forced sedentism

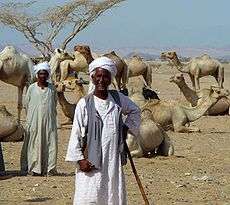

Forced sedentism or sedentarization occurs when a dominant group restricts the movements of a nomadic group. Nomadic populations have undergone such a process since the first cultivation of land; the organization of modern society has imposed demands that have pushed aboriginal populations to adopt a fixed habitat.

At the end of the 19th and throughout the 20th century many previously nomadic tribes turned to permanent settlement. It was a process initiated by local governments, and it was mainly a global trend forced by the changes in the attitude to the land and real property and also due to state policies. Among these nations are Negev Bedouin in Jordan, Israel and Egypt,[8] Bashkirs, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs in Soviet Russia, Tibetan nomads in China,[9] Babongo in Gabon, Baka in Cameroon,[10] Innu in Canada etc.

See also

- Nacirema people

- Western culture

- Indian reservation

- Negev Bedouin

- Nomad

- Seasonal human migration

- Timeline of agriculture and food technology

- Transhumance

References

- ↑ Kris Hirst, Sedentism

- ↑ Ofer Bar-Yosef, The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture Evolutionary Anthropology, taken from the book 'The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture Evolutionary Anthropology', 1998

- ↑ Lieberman D.E., Seasonality and gazelle hunting at Hayonim Cave : new evidence for "sedentism" during the Natufian, Paléorient, 1991, volume 17, issue 17/1, pp.47-57

- ↑ Jomon Fantasy: Resketching Japan's Prehistory. June 22, 1999.

- ↑ "Ancient Jomon of Japan", Habu Junko, Cambridge Press, 2004

- ↑ New Evidence on the Ertebølle Culture on Rugen

- ↑ Lillbergets Stone Age Village

- ↑ The Sedentarization of the Bedouin People

- ↑ Sedentarization of Tibetan Nomads

- ↑ Naoki Matsuura, VISITING PATTERNS OF TWO SEDENTARIZED CENTRAL AFRICAN HUNTER-GATHERERS: COMPARISON OF THE BABONGO IN GABON AND THE BAKA IN CAMEROON, African Study Monographs, 30(3): 137-159, September 2009

External links

| Look up sedentism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Emily A. Schultz, Robert H. Lavenda. The Consequences of Domestication and Sedentism. From a college textbook - Anthropology: A Perspective on the Human Condition Second Edition. pp 196–200

- Keith Weber, Shannon Horst. 2011. Desertification and livestock grazing: The roles of sedentarization, mobility and rest

- David Western, Rosemary Grooma, Jeffrey Worden. 2009. The impact of subdivision and sedentarization of pastoral lands on wildlife in an African savanna ecosystem

- Shuji Sueyoshi, Ryutaro Ohtsuka. 2007. LONG-LASTING EFFECTS OF SEDENTARIZATION-INDUCED INCREASE OF FERTILITY ON LABOR FORCE PROPORTION AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN AN ARAB SOCIEITY: A CASE STUDY IN SOUTH JORDAN

- Fagan, Brian. 2005. Ancient North America. Thames & Hudson, Ltd.: London.

- Halén, Ove. 1994. Sedentariness During the Stone Age of Northern Sweden Almkvist & Wiksell, Stockholm.

- Sofer, Olga. 1981 Sedentism During the Paleolithic

- Habu, Junku. 2004 Ancient Jomon of Japan Cambridge University Press

- Lands of the Negev on YouTube, a short film presented by Israel Land Administration describing the challenges Bedouins face in their sedentarization in Israel's southern Negev region

- Should Pastoralists be sedentarized?, Drylands Coordination Group