Self-perceived quality-of-life scale

The self-perceived quality-of-life scale[1][2] is a psychological assessment instrument which is based on a comprehensive theory of the self-perceived quality of life (SPQL)[3] and provides a multi-faceted measurement of health-related and non-health-related aspects of well-being.[4] The scale has become an instrument of choice for monitoring quality of life in some clinical populations, for example, it was adopted by the Positively Sound network for women living with HIV.[5]

The improvement of mental disorders may have an effect on multiple domains of an individual's life which could be captured only through a comprehensive measurement. For example, the treatment of a phobia may reduce fear (mental health index), which could lead to the improvement of social relations (social relations index) and, in turn, performance at work, resulting in an increase in salary (financial index). Hence, in order to detect all implications of a treatment (e.g., for a phobia), a comprehensive measurement across multiple domains of an individual's life is needed. The SPQL scale can provide such a comprehensive measurement.

The scale is designed in an electronic format. The software calculates scores automatically; this allows for advanced quantification methods. The automatic calculations and quantification methods allowed undertaking a comprehensive approach for assessing SPQL from multiple facets. A multi-facet approach, in turn, provided a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of mental health interventions (through pre- and post tests).

The scale emerged from synthesis of existing theories including: (a) subjective well-being, (b) developmental life-stages, (c) different categories of human needs, (d) quality of life, and (e) subjective evaluation processes. The scale consists of three axes: Subjective well-being, positive and negative affect, and fulfillment of needs. See a model diagram below.

The scale can (a) identify possible side effects of psychiatric or psychological interventions which could occur in multiple domains of an individual’s life, (b) detect the occurrence of relapses, (c) assist in evaluating the progress of recovery, (d) measure the effects of various non-normative positive and negative events (e.g., divorce, promotion at work, becoming a parent) on an individual’s life as a whole and trace the course of their development, (e) evaluate an individual’s SPQL throughout the lifespan, (f) predict depression, anxiety, and mood, and (g) assess the effectiveness of interventions intended to enhance well-being and improve quality of life on an individual level.

This scale could be used by individual mental health professionals to evaluate the progress of treatment. This is useful for clients as well because they themselves are able to compare their initial scores with scores after intervention. Because the scale is available online, clients are able to complete the questionnaire outside of the therapy sessions. The scale also could be used in medical settings to assess how medical treatment affects a patient’s life overall and in specific aspects overtime, as well as allow detecting psychological side effects. The scale could be of use to insurers because it would help in evaluating the effectiveness of mental health interventions.

SPQL model

Theory

It is safe to postulate that all people want to have a good life. Although the meaning of “a good life” may vary from culture to culture and from individual to individual, this meaning revolves around the same aspects of life across cultures. What actually varies between cultures and individuals is the availability of certain aspects of a good life, the subjective significance people assign to these aspects, and the way people evaluate these aspects of a good life.

Everything we do or do not do, wish or do not wish, and have or do not have has an explicit or an implicit relevance to how good or not good we perceive our lives to be. Because the preference for a good life over a bad life underlies all facets of our lives, understanding what constitutes and influences a good life on an individual level has a significant value for all people.

During the past several decades researchers investigated the concept of “the good life” based on three theoretical approaches: (a) focusing on quality of life (QOL) on a population and on individual levels by considering objective and/or subjective factors present or absent in people’s lives (Power, 2004;[6] World Health Organization Quality of Life [WHOQOL] Group, 1995[7]); (b) focusing on subjective well-being (SWB) by considering an individual’s level of overall happiness and life satisfaction (Corey, Keyes, & Magyar-Moe, 2004;[8] Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999;[9] Watson, 2000[10]); and (c) focusing on an individual’s level of functionality across social, psychological, and health factors (Keyes, 1998;[11] Ryff, 1989;[12] Ware & Sherbourne, 1992).

The comprehensive scale of the good life, the Self-Perceived Quality of Life (SPQL) scale, overcame the limitations of prior approaches (Hagerty et al., 2001;[13] Rapley, 2003[14]) by integrating measurements of SWB, QOL, and functionality on an individual level, and by utilizing innovative quantification methods. The scale focused on how individuals evaluate their lives and compare these measurements with the average good life of others. The SPQL scale includes well-being, emotions, and physical and mental health indices. The SPQL scale has implications for evaluating the effectiveness of a wide range of interventions intended to improve mental health and well-being.

Conceptual model

The SPQL construct consists of three axes (see SPQL model diagram): Subjective well-being (SWB), subjective affective experiences (SAE), and fulfillment of needs and preferences. Each axis is compounded from several variables (see SPQL model diagram). SWB consists of its baseline, which is the average of overall happiness/unhappiness, and transient deviations, which are measures of frequency and intensity of nonnormative transient experiences of happiness/unhappiness. Subjective affective experiences (SAE) consist of the average of overall positive and negative affect. Fulfillment of needs consists of a product of strength and fulfillment of a wide range of needs and preferences.

Because fluctuations within SPQL are likely to occur over time, a single-occasion measurement will not provide a comprehensive assessment (Diener, 2000; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005). In order to capture a more comprehensive picture of SPQL, the SWB variable (axis) was measured retrospectively throughout three major life stages of adult human development: Early-adulthood, mid-adulthood, and late-adulthood (see SPQL model diagram).

Transitions between life stages

As people approach a life stage in their development, they face developmental tasks that they need to master in order for the transition to the next life stage to be successful (Erikson, 1968; Harter, 1998, 1999). The cycle of transition from one life stage to another is marked by three phases: (a) Mastering or failing a task; (b) consequential reevaluation of life circumstances, values, and self-concept; and (c) adjustment and adaptation to new values and circumstances. To a lesser degree, cycles of transitions occur continually within major life stages on annual and even on daily bases.

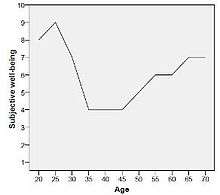

A curve of SWB throughout the lifespan can reflect the experience of an individual’s good life. See Figure 2 for an example of the curve of a 69-year-old person. Ideally, all three SPQL axes should be evaluated for each life stage. However, this would make a questionnaire too long. Although the SPQL scale measures only one SPQL axis (SWB) for each life stage, the developed theoretical framework discusses the evaluation of all three SPQL axes throughout the major life stages. Thus, the framework can support the development of a next version of the scale that would accomplish this goal. Future research could explore possibilities for reducing the number of the evaluated scale items and include questions that will evaluate all three SPQL axes throughout the major life stages.

SPQL axes

Participants’ responses on the inventories for each of the three SPQL axes (see Appendixes) provided the data for the psychometric validation of the scale and for the quantitative analyses that allowed measuring the good life. The theoretical framework for the first two axes was based on the existing theories of SWB, positive affect and negative affect, and mood (Diener et al., 1999; Fredrickson, 1998; Watson, 2000; Watson & Clark, 1994). The theoretical framework for the third axis was based on theories that conceptually differentiate between different categories of needs (Maslow, 1970; Panksepp, 2000). Different categories of needs, in turn, are sorted into four general categories of needs composing the third axis. The measurement of an individual’s level of functionality across social, psychological, and health factors was integrated in the third axis. This integration was accomplished through evaluating the strength and fulfillment of an individual’s needs for optimal functioning across these factors.

Axis I: subjective well-being (SWB)

The SWB baseline is maintained by psychological and biological homeostasis (Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Cummins & Lau, 2004). Measurement of overall happiness determined the SWB baseline. A higher SWB baseline indicates a higher SPQL. People who have experienced more positive and less negative intense experiences during their lives (i.e., transient deviations), have a higher SPQL. Intense experiences were assessed through measuring the frequency and intensity of nonnormative transient subjective experiences of happiness/unhappiness that deviate from the SWB baseline throughout time.

Axis II: subjective affective experiences (SAE)

People who have experienced more positive and less negative subjective affective experiences (SAE) during their lives (i.e., transient deviations), have a higher SPQL. The average of positive and negative SAE was used to measure overall SAE.

Axis III: fulfillment of needs

Individuals with the same score on SWB can differ in their evaluations of standards of living even if their objective life circumstances are alike. Accordingly, their self-perceived QOL may vary. Hence, in order to capture a more accurate measurement of SPQL, the strength and degree of fulfillment of a wide range of human needs and preferences for life circumstances was evaluated. However, felt needs are not the only kind of needs that a person may have (Maslow, 1970). If a need is satisfied it may not be felt as intensely as an unsatisfied need of lesser importance in terms of overall happiness. Thus, the strength with which a need is felt at a certain point in time does not necessarily indicate that it makes a greater contribution to the overall SPQL than other needs, which are felt less intensely or unfelt at all at that point in time because they are satisfied. Hence, the strength of individual preferences and needs was evaluated not only through questions such as “how important is fulfillment of this need to your overall happiness?” but also with questions such as “if this need were unfulfilled, how would it affect your overall happiness?”

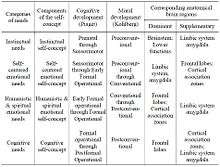

Conceptual model for axis III fulfillment of needs. In order to measure fulfillment of needs, a broad range of human needs was sorted into four conceptually distinct categories (see Table 2) that are (a) contingent on corresponding stages of cognitive and moral development (Kohlberg, Levine, & Hewer, 1983; Piaget, 1952), (b) constitute major components of self-concept (Marcia, 1980), and (c) correspond to the neural activity in different clusters of anatomical brain regions (Berridge, 2004; Lewis, 2000a). Because sometimes the same anatomical brain regions are involved in different ways in neural activity associated with the four categories of needs, implicated brain regions will be distinguished based on their dominance in related processes, and based on the chronological maturation of the dominant regions.

Four categories of needs on axis III

- Instinctual needs include (a) sensory stimulation needs that became linked with positive or negative affect without involvement of cognitive evaluations; (b) physiological needs such as hunger, thirst, and sex; and (c) other physiological needs, such as those related to digestion, fluid balance, body temperature, and blood pressure, which could elicit positive or negative affect depending on whether the needs are met.

- Self-centered emotional needs include (a) needs for safety and security (e.g., financial stability, home), love and belonging (e.g., affectionate relationships, sense of community), esteem (e.g., recognition, confidence); (b) ego-centered self-conscious needs (underpinned by self-conscious emotions, that is, emotions which require self-conscious awareness and evaluations), such as pride and honor (e.g., from personal accomplishments vs. nurturing), and guilt and embarrassment (with a focus on how one’s status has been affected vs. focusing on how others have been affected); and (c) spiritual/religious needs motivated by ego inflation or belonging emotional needs.

- Humanistic and spiritual emotional needs include (a) a higher order of self-conscious altruistic needs that are not self-centered, such as pride and honor (e.g., from nurturing vs. from personal accomplishments), and guilt and embarrassment (with a focus on how others have been affected vs. focusing on how one’s status has been affected); (b) humanistic, self-actualization needs, characterized by a desire to fulfill one’s potential, which are not ego-centered (e.g., desiring truth over dishonesty); and (c) spiritual/religious needs which are not motivated by ego inflation or belonging emotional needs.

- Cognitive needs include needs for harmony, organization, and coherence in (a) aesthetics (e.g., art, architecture, poetry, and music) and (b) intellect (sciences, information, and skills).

Measuring axis III fulfillment of needs

Because according to the SPQL theory an individual’s motivations ensue from the idiosyncratic cluster of the four categories of needs, these four categories are proposed to compound an individual’s motivational framework (MF). In the following discussion, disparate preferences and needs will be referred to as motivational units (MU). Motivational units have two dimensions, importance of MU to the SPQL (strength) and the degree of fulfillment (see Figure 3). The strength of a motivational unit (MU) was determined by evaluating the capacity for the fulfillment or unfulfillment of the MU to skew the SWB baseline.

See also

References

- ↑ Trakhtenberg, E. C. (2008, August). Self-perceived quality of life scale: Theoretical framework and development. Presentation at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, Massachusetts.

- ↑ Trakhtenberg, E. C. (2009). What constitutes happiness? Self-perceived quality of life scale: Theoretical framework and development. Saarbrücken, Germany: VDM. http://www.amazon.com/constitutes-happiness-Self-perceived-quality-scale/dp/3639207165

- ↑ Trakhtenberg, E. C. (2007, August). Enhancing the quality rather than intensity of subjective well-being. Presentation at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, California.

- ↑ Trakhtenberg, E. C. (2008). Self-perceived quality of life scale: Theoretical framework and development (Doctoral dissertation, Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, Palo Alto, CA). Dissertation Abstracts International, 69 (3).

- ↑ http://positivelysound.org/aboutus.htm.

- ↑ Power, M. J. (2004). Quality of life. In S. J. Lopez, & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 427–439). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) Group (1995). World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409.

- ↑ Corey, L. M., Keyes, C. L. M, & Magyar-Moe, J. L. (2004). The measurement and utility of adult subjective well-being. In S. J. Lopez, & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 411–425). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. E. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

- ↑ Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guilford Press.

- ↑ Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(2), 121–140.

- ↑ Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

- ↑ Hagerty, M., Cummins, R., Ferriss, A., Land, K., Michalos, A., Peterson, M., et al. (2001). Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Social Indicators Research, 55, 1–96.

- ↑ Rapley, M. (2003). Quality of life research: A critical introduction. London: Sage.

External links

- To learn more about the Self-Perceived Quality of Life Scale and Theory, go to: www.life-scale.