Wampum

Wampum are traditional shell beads of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of the indigenous people of North America. Wampum include the white shell beads fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell; and the white and purple beads made from the quahog, or Western North Atlantic hard-shelled clam.

Wampum were used by the northeastern Native Americans as a form of gift exchange. Early historians and colonists mistook[1] wampum as a form of money.[2] The colonists then adopted wampum as their own currency; however, the Europeans' more efficient production of wampum caused inflation and ultimately the obsolescence of wampum as currency.

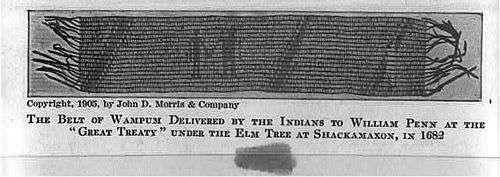

Wampum was often kept on strings like Chinese cash. Before European contact, strings of wampum were used for storytelling, ceremonial gifts, and the recording of important treaties and historical events,[1] such as the Two Row Wampum Treaty.

According to the Onandaga Nation, the wampum is a living record and has many uses. These can include inviting a person to a meeting, showing title, and to show that a speaker holding it is truthful.

See: Onendaga Nation http://www.onondaganation.org/culture/wampum/

Description and manufacture

This term initially referred to only the white beads, which are made of the inner spiral, or columella, of the Channeled whelk shell, Busycotypus canaliculatus or Busycotypus carica.[3] Sewant or suckauhock beads are the black or purple shell beads made from the quahog or poquahock clamshell, Mercenaria mercenaria. Sewant or Zeewant was the term used for this currency by the New Netherland colonists.[4] Common terms for the dark and white beads, often confused, are wampi (white and yellowish) and saki (dark).[5]

In the area of present New York Bay, the clams and whelks used for making wampum are found only along Long Island Sound and Narragansett Bay. The Lenape name for Long Island is Sewanacky, reflecting its connection to the dark wampum.

Typically wampum beads are tubular in shape, often a quarter of an inch long and an eighth inch wide. One 17th-century Seneca wampum belt featured beads almost 2.5 inches (65 mm) long.[3] Women artisans traditionally made wampum beads by rounding small pieces of the shells of whelks, then piercing them with a hole before stringing them.

Wooden pump drills with quartz drill bits and steatite weights were used to drill the shells. The unfinished beads would be strung together and rolled on a grinding stone with water and sand, until they were smooth. The beads would be strung or woven on deer hide thongs, sinew, milkweed bast, or basswood fibers.[6]

Care must be taken while crafting or incising wampum. If one does not keep the shell wet while drilling or scratching, the shell will crack, split, or break. The same trouble occurs if one tries to remove too much material at once.

Origin

The term "wampum" is a shortening of the earlier word "wampumpeag", which is derived from the Massachusett or Narragansett word meaning "white strings [of shell beads]".[6][7] The Proto-Algonquian reconstructed form is *wa·p-a·py-aki, "white-string-plural."[8]

In New York, wampum beads have been discovered from before 1510.[3] The Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace, the founding constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy, was codified in a series of wampum belts, now held by the Onondaga Nation. The oral history of the Haudenosaunee says that Ayenwatha, a cannibal who was reformed by the Great Peacemaker, invented wampum to comfort himself. The Peacemaker used wampum to record and relay messages.[9] The League of the Iroquois was founded, according to some estimates, in 1142.[10] Others place its origin as likely in the 15th or 16th centuries.

The introduction of European metal tools revolutionized the production of wampum; by the mid-seventeenth century production numbered in the tens of millions of beads.[11] Upon discovering the importance of wampum as money for exchange between tribes, Dutch colonists mass-produced wampum in workshops. John Campbell established such a factory in Passaic, New Jersey, which manufactured wampum into the early 20th century.[3]

Uses

Currency

The use of wampum beads has been much debated throughout the years with many claiming that Aboriginal people used the beads as currency. For the Haudenosaunee, wampum held a more sacred use. Wampum served as a person’s credentials or a certificate of authority. It was used for official purposes and religious ceremonies and in the case of the joining of the League of Nations was used as a way to bind peace. Every Chief of the Confederacy and every Clan Mother has a certain string or strings of Wampum that serves as their certificate of office. When they pass on or are removed from their station the string will then pass on to the new leader. Runners carrying messages would not be taken seriously without first presenting the wampum showing that they had the authority to carry the message.[12]

As a method of recording and an aid in narrating, Haudenosaunee warriors with exceptional skills were provided training in interpreting the wampum belts. As the Keepers of the Central Fire the Onondaga Nation was also trusted with the task of keeping all wampum records. To this day wampum is still used in the ceremony of raising up a new chief and in the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving ceremonies. True wampum is scarce today and only wampum strings are used. Many belts have been lost or are in museums to this day.[13]

When Europeans came to the Americas, they adopted wampum as money to trade with the native peoples of New England and New York. Wampum was legal tender in New England from 1637-1661. Meanwhile, it continued as currency in New York at the rate of eight white or four black wampum equalling one stuiver—meaning the white had the same value as the copper duit coin—until 1673. The colonial government issued a proclamation setting the rate at six white or three black to one penny. This proclamation also applied in New Jersey and Delaware.[14] The black shells were rarer than the white shells, and so were worth more, which led people to dye the latter, and diluted the value of black shells.[15]

Writing about tribes in Virginia in 1705, Robert Beverley, Jr. of Virginia Colony describes peak as referring to the white shell bead, valued at 9 pence a yard, and wampom peak as denoting specifically the more expensive dark purple shell bead, at the rate of 1 shilling and 6 pence (18 pence) per yard. He says that these polished shells with drilled holes are made from the cunk (conch), while another currency of lesser value, called roenoke was fashioned from the cockleshell.[16]

With stone tools, the process to make wampum was labor-intensive. Only the coastal nations had sufficient access to the basic shells to make wampum. These factors increased its scarcity and consequent value among the European traders. Dutch colonists began to manufacture wampum and eventually the primary source of wampum was that manufactured by colonists, a market the Dutch glutted.

Wampum briefly became legal tender in North Carolina in 1710, but their use as common currency died out in New York by the early 18th century.

Transcription

The American William James Sidis wrote in his 1935 history;

The weaving of wampum belts is a sort of writing by means of belts of colored beads, in which the various designs of beads denoted different ideas according to a definitely accepted system, which could be read by anyone acquainted with wampum language, irrespective of what the spoken language is. Records and treaties are kept in this manner, and individuals could write letters to one another in this way.[17]

Perhaps because of its origin as a memory aid, loose beads that were within a common size, shape, and color spectrum were usually not considered to be high in value. Conversely, large ornate, storytelling belts were valued much more highly. Belts of wampum were not mass-produced until after European contact. A typically large belt of six feet (2 m) in length might contain 6000 beads or more. Wampum belts were used as a memory aid in oral tradition, where writing could be encoded in wampum strings. Belts were also sometimes used as badges of office or as ceremonial devices of indigenous culture, such as the Iroquois. They were traded widely to tribes in Canada, the Great Lakes region, and the mid-Atlantic.

The mark of authority one had when one carried wampum is an important thing. Carriers often earned wampum for saying hard things, instead of taking the easy path. The 1820 New Monthly Magazine reports on a fiery speech given by the chief Tecumseh, in which he vehemently gesticulated to a belt, pointing out treaties made 20 years earlier and battles fought since then.[18]

It is also important to note that wampum belts are read right-to-left, not the left-to-right direction common to most written European languages used in the early post-Columbian period.

Wampum was also used for storytelling. The symbols used told a story in the oral tradition or spoken word. Since there was no written language, wampum was a very important means of keeping records and passing down stories to the next generation. Wampum was durable and so could be carried over a long distance.

Recent developments

The National Museum of the American Indian repatriated eleven wampum belts to Haudenosaunee chiefs at the Onondaga Longhouse Six Nations Reserve in New York. Sacred to the Longhouse religion, these belts dated to the late 18th century. They had been away from their tribes for over a century.[3]

Cayuga, Shinnecock, Wampanoag, and other Northeastern Woodland tribes still use wampum today. The Seneca Nation commissioned replicas of five historic wampum belts completed in 2008. Artists continue to weave belts of a historical nature as well as designing original belts based on contemporary concepts.[6]

Symbolic use

The flag of the Iroquois Confederacy is a wampum-belt design.

See also

- Great Law of Peace

- The Hiawatha Belt

- Economy of the Iroquois

- Shell money

- Quipu, Quechua recording devices made of knotting and dyed strings

References

- 1 2 http://web.grinnell.edu/courses/edu/f01/edu315-01/liberato/wampum.html

- ↑ http://szabo.best.vwh.net/shell.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dubin, Lois Sherr. North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment: From Prehistory to the Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999: 170-171. ISBN 0-8109-3689-5.

- ↑ Jaap Jacobs. The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-century America. Cornell University Press, 2009. pg. 14

- ↑ Geary, Theresa Flores. The Illustrated Bead Bible. London: Kensington Publications, 2008: 305. ISBN 978-1-4027-2353 -7.

- 1 2 3 Perry, Elizabeth James. About the Art of Wampum. Original Wampum Art: Elizabeth James Perry. 2008 (retrieved 14 March 2009)

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Wampum". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- ↑ "Wampumpeag". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- ↑ Gawyehnehshehgowa: Great Law of Peace. Degiya'göh Resources. (retrieved 14 March 2009)

- ↑ Johansen, Bruce E. "Dating the Iroquois Confederacy", Akwesasne Notes, Fall 1995, Volume 1, 3 & 4, pp. 62-63. (retrieved through Ratical.com, 14 March 2009)

- ↑ Otto, Paul "Henry Hudson, the Munsees, and the Wampum Revolution" (retrieved 5 September 2011)

- ↑ http://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/hiawatha.html

- ↑ http://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/wampum.html

- ↑ Samuel Smith, The History of New Jersey p. 76

- ↑ "Wampum: Introduction" author Louis Jordan

- ↑ Robert Beverley, The History and Present State of Virginia

- ↑ William James Sidis, The Tribes And The States: 100,000-Year History of North America

- ↑ New Monthly Magazine Vol. 14 p.522 https://books.google.com/books?id=uDoaAQAAIAAJ

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wampum. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Wampum. |

- Wampum article, Iroquois Indian Museum

- Wampum History and Background

- "The Tribes And The States: 100,000-Year History of North America"

- X-ray showing inner spiral and entire shell of the Busycotypus Canaliculatus - Channeled Whelk Shell, Europa

- "Money Substitutes in New Netherland and Early New York", Coins, University of North Dakota