Shipibo-Conibo people

| |||

| Total population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (11,000-25,000) | |||

| Languages | |||

| Shipibo | |||

The Shipibo-Conibo are an indigenous people along the Ucayali River in the Amazon rainforest in Perú. Formerly two groups, the Shipibo (apemen) and the Conibo (fishmen), they eventually became one distinct tribe through intermarriage and communal ritual and are currently known as the Shipibo-Conibo people.[1][2]

Lifestyle, tradition and diet

The Shipibo-Conibo live in the 21st century while keeping one foot in the past, spanning millennia in the Amazonian rainforest. Many of their traditions are still practiced, such as ayahuasca shamanism. Shamanistic songs have inspired artistic tradition and decorative designs found in their clothing, pottery, tools and textiles. Some of the urbanized people live around Pucallpa in the Yarina Cocha, an extensive indigenous zone. Most others live in scattered villages over a large area of jungle forest extending from Brazil to Ecuador.

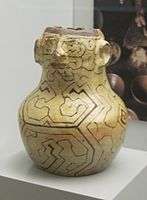

Shipibo-Conibo women make beadwork and textiles, but are probably best known for their pottery, decorated with maze-like red and black geometric patterns. While these ceramics were traditionally made for use in the home, an expanding tourist market has provided many households with extra income through the sale of pots and other craft items. They also prepare chapo, a sweet plantain beverage.

The Shipibo of the village of Pao-Yan used to have a diet of fish, yuca and fruits. Now, however, the situation has deteriorated because of global weather changes and now there is mostly just yuca and fish. Since there has been drought followed by flooding, most of the mature fruit trees have died, and some of the banana trees and plantains are struggling. Global increases in energy and food prices have risen due to deforestation and erosion along the Ucayali River. The basic needs of the people are more important now than ever, affecting their long term planning abilities. There is now a sense that hunger may not be that far off for those in the farther reaches of the Shipibo nation.[2][3]

Contact with western sources – including the governments of Peru and Brazil – has been sporadic over the past three centuries. The Shipibo are noted for a rich and complex cosmology, which is tied directly to the art and artifacts they produce. Christian missionaries have worked to convert them since the late 17th century,[4][5] particularly from the Franciscans.[6]

Population

With an estimated population of over 20,000, the Shipibo-Conibo represent approximately 8% of the indigenous registered population. Census data is unreliable due to the transitory nature of the group. Large amounts of the population have relocated to urban areas – in particular the eastern Peruvian cities of Pucallpa and Yarinacocha – to gain access to better educational and health services, as well as to look for alternative sources of monetary income.

The population numbers for this group have fluctuated in the last decades between approximately 11,000 (Wise and Ribeiro, 1978) to as many as 25,000 individuals (Hern 1994).

Like all other indigenous populations in the Amazon basin, the Shipibo-Conibo are threatened by severe pressure from outside influences such as oil speculation, logging, narco-trafficking, and conservation.[7][8]

Known authorities

- Donald W Lathrap

- Warren de Boer

- James A Lauriault/Loriot

- Earwin H Lauriault

See also

References

- ↑ Eakin, Lucile; Erwin Laurialy; Harry Boonstra (1986). "People of the Ucayali: The Shipibo and Conibo of Peru". International Museum of Cultures Publication: 62.

- 1 2 "The Shipibo-Conibo Amazon Forest People at the Dawn of the 21st Century".

- ↑ Bradfield, R.B; James Lauriault (1961). "Diet and food beliefs of Peruvian jungle tribes: 1. The Shipibo (monkey people)". Journal of the American Dietetic (39): 126–28.

- ↑ Eakin, Lucille; Erwin Lauriault; Harry Boonstra (1980). "Bosquejo etnográfico de los shipibo-conibo del Ucayali". Lima: 101.

- ↑ Kensinger, Kenneth M (1985). "Panoan linguistic, folklorisic and ehtnographic research: retrospect and prospect". South American Indian languages: retrospect and prospect: 224–85.

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sipibo Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sipibo Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Bardales R., César (1979). "Quimisha Incabo ini yoia (Leyendas de los shipibo-conibo sobre los tres Incas)". Comunidades y Culturas Peruanas (12): 53.

- ↑ Eakin, Lucille. "Nuevo destino: The life story of a Shipibo bilingual eduactor". Summer Institute of Linguistics Museum of Anthropology publication (9): 26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shipibo-Conibo. |

- at the Shipibo Conibo Center of New York, NY

- Shipibo art at the National Museum of the American Indian

- Conibo art at the National Museum of the American Indian

Further reading

- Olson, James Stuart (1991). "Shipibo". The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 330–31. ISBN 978-0-313-26387-3. OCLC 22381053.

- Kennedy, Lauren. "La pobreza móvil de los migrantes Shipibo-Conibo: Una investigación de la influencia de la migración en la cosmovisión Shipibo-Conibo de Canta Gallo-Rímac, Lima" (2011)" [An investigation into the influence of migration on the Shipibo-Conibo worldview in Canta Gallo-Rimac]. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection (in Spanish) (Paper 1080).