Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

| Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A 2D profile drawing of Rainbow Warrior. | |||

| Date | 10 July 1985 | ||

| Location | Port of Auckland, New Zealand | ||

| Causes | Protests by Greenpeace against French nuclear testing | ||

| Goals | To sink Rainbow Warrior | ||

| Methods | Bombing | ||

| Result | Rainbow Warrior sunk, 1 person killed | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

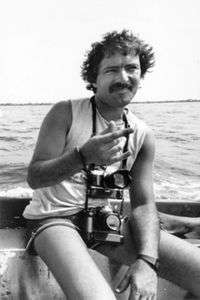

The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior, codenamed Opération Satanique,[1] was a bombing operation by the "action" branch of the French foreign intelligence services, the Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure (DGSE), carried out on 10 July 1985. During the operation, two operatives sank the flagship of the Greenpeace fleet, the Rainbow Warrior in the port of Auckland, New Zealand on its way to a protest against a planned French nuclear test in Moruroa. Fernando Pereira, a photographer, drowned on the sinking ship.

France initially denied responsibility, but two French agents were captured by New Zealand Police and charged with arson, conspiracy to commit arson, willful damage, and murder. As the truth came out, the scandal resulted in the resignation of the French Defence Minister Charles Hernu.

The two agents pleaded guilty to manslaughter and were sentenced to ten years in prison. They spent just over two years confined to the French island of Hao before being freed by the French government.[2]

Sinking of the ship

French agents posing as interested supporters or tourists toured the ship while it was open to public viewing. DGSE agent Christine Cabon, posing as environmentalist Frederique Bonlieu, volunteered to work in the Greenpeace office in Auckland. Cabon "was no ordinary lieutenant...a veteran of many dangerous intelligence missions in the Middle East, particularly in Lebanon."[3] Cabon secretly monitored communications from the Rainbow Warrior, collected maps, and investigated underwater equipment, in order to provide information crucial to the sinking.

After the necessary information had been gathered two DGSE divers, Jacques Camurier and Alain Tonel, attached two limpet mines to the Rainbow Warrior berthed at Marsden Wharf and detonated them 10 minutes apart.[4] The first bomb went off at 11:38 p.m., blasting a hole about the size of an average car. Agents intended the first mine to cripple the ship so that it would be evacuated safely by the time the second mine was detonated. However, the crew did not react to the first explosion as the agents had expected. While the ship was initially evacuated, some of the crew returned to the ship to investigate and film the damage. A Portuguese-Dutch photographer, Fernando Pereira, returned below decks to fetch his camera equipment. At 11:45 p.m., the second bomb went off. Pereira drowned in the rapid flooding that followed, and the other ten crew members either safely abandoned ship on the order of Captain Peter Willcox or were thrown into the water by the second explosion. The Rainbow Warrior sank four minutes later.

France implicated

Operation Satanique was a public relations disaster. France, being an ally of New Zealand, initially denied involvement and joined in condemning what it described as a terrorist act. The French embassy in Wellington denied involvement, stating that "the French Government does not deal with its opponents in such ways".[5]

After the bombing, the New Zealand Police started one of the country's largest police investigations. Most of the agents of the French team escaped from New Zealand but two, Captain Dominique Prieur and Commander Alain Mafart were identified as possible suspects. Posing as the married couple Sophie and Alain Turenge, Prieur and Mafart were identified with the help of a Neighbourhood Watch group, and arrested. Both were questioned and investigated. Because they were carrying Swiss passports, their true identities were discovered, along with the French government's responsibility.

Three other agents, Chief Petty Officer Roland Verge, Petty Officer Bartelo and Petty Officer Gérard Andries, who sailed to New Zealand on the yacht Ouvéa, were arrested by Australian police on Norfolk Island, but released as Australian law did not allow them to be held until the results of forensic tests came back. They were then picked up by the French submarine Rubis, which scuttled the Ouvéa.[6]

A sixth agent, Louis-Pierre Dillais, commander of the operation, was never captured and never faced charges. He acknowledged his involvement in an interview with New Zealand state broadcaster TVNZ in 2005.[7]

Once it was realised that the bombing was the action of the government of a friendly state, the New Zealand government stopped referring to it as a "terrorist act", instead calling it "a criminal attack in breach of the International Law of State Responsibility, committed on New Zealand sovereign territory". The "Breach of International Law" aspect was referred to in all communications with the United Nations in order to dissuade any arguments from the French government that might imply justification for their act.

More than 30 years on, TVNZ's Sunday programme tracked down the French spy who planted the bombs. Jean Cammas, who retired from the DGSE in about 2000, confessed to planting both bombs on the hull of the ship. While using the alias Jacques Camurier, after the bombing on July 10, Cammas and several others posed as tourists, taking the ferry to the South Island and skied at Mt Hutt, then left the country on false documents about 10 days later. Reporter John Hudson, who spent two days with Cammas in France, said "At the end of the day he was a guy who wanted an opportunity to talk about his role in the bombing... It has been on his conscience for 30 years. He said to us, 'secret agents don't talk', but he is talking. I think he wanted to be understood." Cammas considered the mission "a big, big failure".[8]

Prieur and Mafart pleaded guilty to manslaughter and were sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment on 22 November 1985. France threatened an economic embargo of New Zealand's exports to the European Economic Community if the pair were not released.[9] Such an action would have crippled the New Zealand economy, which was dependent on agricultural exports to the United Kingdom.

A commission of enquiry headed by Bernard Tricot cleared the French government of any involvement, claiming that the arrested agents, who had not yet pleaded guilty, had merely been spying on Greenpeace. When The Times and Le Monde claimed that President Mitterrand had approved the bombing, Defence Minister Charles Hernu resigned and the head of the DGSE, Admiral Pierre Lacoste, was fired. Eventually, Prime Minister Laurent Fabius admitted the bombing had been a French plot: On 22 September 1985, he summoned journalists to his office to read a 200-word statement in which he said: "The truth is cruel," and acknowledged there had been a cover-up, he went on to say that "Agents of the French secret service sank this boat. They were acting on orders."[10]

Aftermath

Nuclear testing

In the wake of the bombing, a flotilla of private New Zealand yachts sailed to Moruroa to protest against a French nuclear test.

At that time, French nuclear tests in the Pacific were halted. However, another series of tests was conducted in 1995.[11]

Greenpeace and the Rainbow Warrior

A Greenpeace Rainbow Warrior benefit concert at Mt. Smart Stadium, Auckland, on 5 April 1986 included performances by Herbs, Neil Young, Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Topp Twins, Dave Dobbyn and a Split Enz reunion.[12][13]

The Rainbow Warrior was refloated for forensic examination. She was deemed irreparable and scuttled at 34°58′29″S 173°56′06″E / 34.9748°S 173.9349°E in Matauri Bay, near the Cavalli Islands, on 12 December 1987, to serve as a dive wreck and fish sanctuary.[14] Her masts had been removed and put on display at the Dargaville Maritime Museum.

On 14 October 2011, Greenpeace launched a new sailing vessel called Rainbow Warrior III, which is equipped with an auxiliary electric motor.[15]

Reparations

In 1987, after international pressure, France paid $8.16m to Greenpeace in damages, which helped finance another ship.[16][17] It also paid compensation to the Pereira family, reimbursing his life insurance company for 30,000 guilders and making reparation payments of 650,000 francs to Pereira's wife, 1.5 million francs to his two children, and 75,000 francs to each of his parents.[18]

Foreign relations

The failure of western leaders to condemn this violation of a friendly nation's sovereignty caused a great deal of change in New Zealand's foreign and defence policy.[19] New Zealand distanced itself from its traditional ally, the United States, and built relationships with small South Pacific nations, while retaining excellent relations with Australia and, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom.[20]

.jpg)

In June 1986, in a political deal with Prime Minister of New Zealand David Lange, presided over by United Nations Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, France agreed to pay NZ$13 million (USD$6.5 million) to New Zealand and apologise, in return for which Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieur would be detained at the French military base on Hao Atoll for three years. However, the two agents had both returned to France by May 1988, after less than two years on the atoll. Mafart returned to Paris on 14 December 1987 for medical treatment, and was apparently freed after the treatment. He continued in the French Army and was promoted to colonel in 1993. Prieur returned to France on 6 May 1988, because she was pregnant, her husband having been allowed to join her on the atoll. She, too, was freed and later promoted. The removal of the agents from Hao without subsequent return was ruled to be in violation of the 1986 agreement.[2]

Following the breach of the arrangement, in 1990 the Secretary-General awarded New Zealand another NZ$3.5 million (USD$2 million), to establish the New Zealand / France Friendship Fund.[17] Although France had formally apologised to the New Zealand Government in 1986,[21] during a visit in April 1991 French Prime Minister Michel Rocard delivered a personal apology.[22][23] He said it was "to turn the page in the relationship and to say, if we had known each other better, this thing never would have happened". The Friendship fund has provided contributions to a number of charity and public purposes.[24] During a visit in 2016, French Prime Minister Manuel Valls reiterated that the incident had been "a serious error".[25]

Further investigations

In 2005, French newspaper Le Monde released a report from 1986 which said that Admiral Pierre Lacoste, head of DGSE at the time, had "personally obtained approval to sink the ship from the late president François Mitterrand." Soon after the publication, former Admiral Lacoste came forward and gave newspaper interviews about the situation, admitting that the death weighed on his conscience and saying that the aim of the operation had not been to kill.[26] He acknowledged the existence of three teams: the yacht crew, reconnaissance and logistics (those successfully prosecuted), plus a two-man team that carried out the bombing.[27][4]

A 20th anniversary memorial edition of the 1986 book Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior by New Zealand author David Robie – who was aboard the bombed ship – was published in July 2005.[28]

The French agents

Twenty years after the bombing, Television New Zealand (TVNZ) sought access to a video record made at the preliminary hearing in which the two French agents pleaded guilty. The footage had remained sealed since shortly after the conclusion of the criminal proceedings. The two agents opposed release of the footage—despite having both written books on the incident—and unsuccessfully took the case to the New Zealand Court of Appeal and, subsequently, the Supreme Court of New Zealand. On 7 August 2006, judges Hammond, O'Regan and Arnold dismissed the former French agents' appeal and TVNZ broadcast their guilty pleas the same day.[29]

In 2006, Antoine Royal revealed that his brother, Gérard Royal, had claimed to be involved in planting the bomb. Their sister is French Socialist Party politician Ségolène Royal who was contesting the French presidential election.[30][31] Other sources identified Royal as merely a Zodiac pilot,[32] and the New Zealand government announced there would be no extradition request since the case was closed.[33]

In 1993, Louis-Pierre Dillais was appointed to an elite espionage position in the office of Defence Minister Francois Leotard.[34] He later became an executive in the U.S. subsidiary of Belgian arms manufacturer FN Herstal and as of May 2007 lived in the Virginia in the United States.[7] In 2007 the New Zealand Green Party criticized the government over its purchase of arms from FN Herstal.[35] At that time, Greenpeace was still pursuing the extradition of Dillais for his involvement in the act.[36]

Jean-Luc Kister, leader of the French operation, spoke to TVNZ in 2015 admitting his lead role and feelings of responsibility for the lethal attack. He also pointed to the French President, as commander of the armed forces and intelligence services assigned the operation.[37][38]

See also

- Rainbow Warrior (1955)

- Rainbow Warrior Case (international law)

- The Rainbow Warrior Conspiracy (1988)

- The Rainbow Warrior (film)

- Legend of the Rainbow Warriors

- New Zealand's nuclear-free zone

- Xavier Maniguet

References

- ↑ Bremner, Charles (11 July 2005). "Mitterrand ordered bombing of Rainbow Warrior, spy chief says". The Times. London. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- 1 2 "Case concerning the difference between New Zealand and France concerning the interpretation or application of two agreements, concluded on 9 July 1986 between the two states and which related to the problems arising from the Rainbow Warrior Affair" (PDF). Reports of International Arbitral Awards. XX: 215–284, especially p 275. 30 April 1990.

- ↑ The French Government and Greenpeace Agents back in court on Friday The Canberra Times, 20 November 1985, at Trove

- 1 2 "At the end of the Rainbow". New Zealand Herald. Jul 8, 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ Diary Compiled by Mike Andrews (Secretary of the Dargaville Maritime Museum)

- ↑ "The Bombing of the Warrior". Rainbow Warrior home page. Greenpeace. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- 1 2 Goldenberg, Suzanne (25 May 2007) "Rainbow Warrior ringleader heads firm selling arms to US government". guardian.co.uk, Retrieved 26 May 2007

- ↑ Taylor, Phil (September 6, 2015). "Rainbow Warrior bomber finally unmasked". NZ Herald. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ↑ Shabecoff, Philip (3 October 1987). "France Must Pay Greenpeace $8 Million in Sinking of Ship". New York Times. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ↑ Evening Mail – Monday 23 September 1985

- ↑ "Fifth French nuclear test sparks international outrage". CNN. 28 December 1995. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ "Rainbow Warrior music festival". NZHistory. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Rainbow Warrior concert 1986". Frenz Forum. 14 July 2006. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Wreck to reef-the transfiguration of the Rainbow Warrior". New Zealand Geographic (023). Jul–Sep 1994. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Rainbow Warrior Greenpeace International, October 2011. Accessed 10 February 2015

- ↑ Willsher, Kim (6 September 2015). "French Spy who sank Greenpeace ship apologises for lethal bombing". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- 1 2 Boczek, Boleslaw Adam (2005). International Law: A Dictionary. Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 97. ISBN 0-8108-5078-8. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS : Case concerning the differences between New Zealand and France arising from the Rainbow Warrior affair (PDF). United Nations. 6 July 1986. pp. 199–221. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Keith Sinclair, A History of New Zealand Penguin Books, New Zealand, 1991

- ↑ Nuclear Free: The New Zealand Way, The Right Honourable David Lange, Penguin Books, New Zealand, 1990

- ↑ "French send PM letters of apology". Auckland: Auckland Star. 23 July 1986.

- ↑ Armstrong, John (2 July 2005). "Reality behind the Rainbow Warrior outrage". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov (2004). From Conflict Resolution to Reconciliation. Oxford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-19-516643-4. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "Kokako Chick thrives thanks to Rainbow Warrior bombers". NZME Publishing Limited. New Zealand Herald. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ Young, Audrey (2 May 2016). "France reaches out for Kiwi friendship". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Simons, Marlise. "Report Says Mitterrand Approved Sinking of Greenpeace Ship". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Field, Catherine (30 June 2005). "'Third team' in Rainbow Warrior plot". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ "Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior". Auckland University Press. 15 July 2005. ISBN 9781877314469. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ Transcript Mafart Prieur v TVNZ, PDF document, 195Kb, 22 November 2005, Retrieved 22 September 2010

- ↑ NZH Staff (30 September 2006). "Presidential hopeful's brother linked to Rainbow Warrior bomb". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ↑ "NZ rules out new Rainbow Warrior probe". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 October 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ↑ Guerres secrètes à l'Élysée, by Paul Barril, ed Albin Michel, Paris (1996)

- ↑ Kay, Martin (2 October 2006). "French frogman slips the net; Paper identifies bomber, but PM says the case will remain closed". The Dominion Post. pp. A1.

- ↑ In Brief: Once a spy... The Canberra Times, 24 June 1993, at Trove

- ↑ NZ trades with Arms Company whose US chief executive was a lead agent in the Rainbow Warrior bombing NZ Green Party Just Peace newsletter No 110, 18 May 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2015

- ↑ Greenpeace gunning for the leader of Warrior bombers Stuff.co.nz, Retrieved 26 May 2007

- ↑ "New Zealand Greenpeace Rainbow Warrior bomber apologises - BBC News". Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ↑ Neuman, Susan (6 September 2015). "French Agent Apologizes For Blowing Up Greenpeace Ship In 1985". NPR. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

Further reading

- Michael King, Death of the Rainbow Warrior (Penguin Books, 1986). ISBN 0-14-009738-4

- David Robie, Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior (Philadelphia: New Society Press, 1987). ISBN 0-86571-114-3

- The Sunday Times Insight Team, Rainbow Warrior: The French Attempt to Sink Greenpeace (London: Century Hutchinson Ltd, 1986). ISBN 0-09-164360-0

External links

- The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior – impact on New Zealand's international relations.

- greenpeace.org.au

- New Zealand police history

- "French Connections" Transcript of the 1985 investigation by the Australian program Four Corners.

- 2010 documentary by Journeyman Pictures for TVNZ

- Detail text and letter from NZ PM D. Lange regarding incident in 'Sailing The Dream' at Google Books

Films (all are productions for television):

- The Rainbow Warrior Conspiracy at the Internet Movie Database (Australia 1989)

- The Rainbow Warrior at the Internet Movie Database (New Zealand 1992)

- The Boat and the Bomb at the Internet Movie Database (United Kingdom and Netherlands 2005)

- L' Affaire du Rainbow Warrior at the Internet Movie Database (France 2006, concentrating on the experience of French journalists)

- Blowing Up Paradise 2006 BBC Documentary movie by Ben Lewis about French Atomic Testing in Pacific and associated murder of Rainbow Warrior Greenpeace activist by French Secret Service.

Coordinates: 36°50′33″S 174°46′18″E / 36.842405°S 174.771579°E

.jpg)