Society of Friends (Upper Canada)

| Part of a series on the |

| Quakers in Canada |

|---|

| Timeline |

| Meetings |

|

|

The Quakers (Society of Friends) immigrated from New York, the New England States and Pennsylvania. They are a pacifist religion, and during this period were also a "plain folk" rejecting all ornamentation in clothing, speech and meeting houses (churches). The Children of Peace were founded during the War of 1812 after a schism in York County. A further schism occurred in 1828, leaving two branches, "Orthodox" Quakers and "Hicksite" Quakers.

Settlement

Preparative meetings and chain migration

The basic unit of Quaker organization is the Monthly Meeting, in reference to its monthly business meeting. The Monthly Meeting admitted members, disciplined them, and created committees of oversight. The Monthly Meeting had oversight of its constituent meetings for worship, which, when meeting for business, were called Preparative Meetings. The Monthly Meeting, in turn, reported to a Quarterly or Half Yearly regional meeting, which in turn joined other regional meetings in a Yearly Meeting.

Quaker settlers who planned on moving were to request a "minute of membership" to bring to the Quaker meeting in their new neighbourhood. This was to ensure that Quakers remained in touch even in frontier regions. As Quakers moved westward, into unsettled regions like Upper Canada, their home meeting might authorize a new Preparative Meeting in that locale. Nine Partners Monthly Meeting in the lower Hudson River Valley of New York state thus authorized a Preparative Meeting for its emigrating members to West Lake in the Bay of Quinte region of Upper Canada in 1798. These new Canadian meetings thus remained in touch with their home meetings (and relatives left behind) and their Yearly Meeting. They also served as a receiving station, easing the flow of settlers from east to west and ensuring they had an established network of Friends to turn to. This is a classic example of the process known as chain migration.

Testimonies

Peace testimony

Friends' peace testimony is largely derived from beliefs arising from the teachings of Jesus to love one's enemies and Friends' belief in the inner light. Quakers believe that nonviolent confrontation of evil and peaceful reconciliation are always superior to violent measures. Peace testimony does not mean that Quakers engage only in passive resignation; in fact, they often practice passionate activism. The Peace Testimony is probably the best known testimony of Friends. Because of their peace testimony, Friends are considered as one of the historic peace churches.

Consensus

Governance and decision making is conducted at a special meeting for worship—often called a meeting for worship with a concern for business or meeting for worship for church affairs at which all members can attend. As in a meeting for worship, each member is expected to listen to God and, if led by Him, stand up and contribute. In some business meetings, Friends wait for the clerk to acknowledge them before speaking. Direct replies to someone's contribution are not permitted, with an aim of seeking truth rather than of debating. A decision is reached when the meeting, as a whole, feels that the "way forward" has been discerned (also called "coming to unity"). There is no voting. On some occasions a single Friend delays a decision because they feel the meeting is not following God's will. Because of this, many non-Friends describe this as consensus decision-making; however Friends are instead determined to continue seeking God's will. It is assumed that if everyone is listening to God's spirit, the way forward will become clear.

Gender and racial equality

Friends believe that all people are created equal in the eyes of God. Since all people embody the same divine spark all people deserve equal treatment. Friends were some of the first to value women as important ministers and to campaign for women's rights; they became leaders in the anti-slavery movement, and were among the first to pioneer humane treatment for individuals with mental disorders, and for prisoners.

Quakers hold a strong sense of spiritual egalitarianism, including a belief in the spiritual equality of the sexes, who were held "separate but equal." Each gender had separate Meetings for Business. This practice was considered to give the women more power and was not meant to demean them. During the 18th century, some Quakers felt that women were not participating fully in Meetings for Business as most women would not "nay-say" their husbands. The solution was to form the two separate Meetings for Business. Many Quaker meeting houses were built with a movable divider down the middle. During Meetings for Worship, the divider was raised, although men and women remained in their separate sections. During Business meetings the divider was lowered, creating two rooms. Each gender ran their own separate business meetings. Any issue which required the consent of the whole meeting—building repairs for example—would involve sending an emissary to the other meeting.

Quakers were also prominently involved with the Underground Railroad. For example, Levi Coffin started helping runaway slaves as a child in North Carolina. Later in his life, Coffin moved to the Ohio-Indiana area, where he became known as the President of the Underground Railroad. Elias Hicks penned the 'Observations on the Slavery of the Africans' in 1811 (2nd ed. 1814), urging the boycott of the products of slave labor. Many families assisted slaves in their travels through the Underground Railroad, to ultimately settle in Upper Canada.

Spontaneous ministry

In this period, Friends adhered to the practice of spontaneous ministry. They would gather together in "expectant waiting upon God" to experience his voice leading them from within. There is no plan on how the meeting will proceed. Friends believe that God plans what will happen, with his spirit leading people to speak. When an individual Quaker feels led to speak, he or she will rise to their feet and share a spoken message ("vocal ministry") in front of others. When this happens, Quakers believe that the spirit of God is speaking through the speaker. After someone has spoken, more than a few minutes pass in silence before further vocal ministry is given. Sometimes a meeting is entirely silent, sometimes many speak. Those who worship in this style hold each person to be equal before God and capable of knowing the light directly. Both men and women could minister. Anyone present may speak if they feel led to do so. Traditionally, Recorded Ministers were recognised for their particular gift in vocal ministry.

Plain style

Friends believed that it was important to avoid fanciness in dress, speech, and material possessions, because those things tend to distract one from waiting on God’s personal guidance. They also tend to cause a person to focus on himself more than on his fellow human beings, in violation of Jesus’ teaching to “love thy neighbor as thyself.” This emphasis on plainness, as it was called, made the Friends in certain times and places easily recognizable to the society around them, particularly by their plain dress in the 18th and 19th Centuries.[1]

Friends tradition of simplicity in dress, more properly called Plain dress generally meant wearing clothes that were very similar to Amish or conservative Mennonite dress: often in dark colors and lacking adornments such as fancy (or any) pockets, buttons, buckles, lace, or embroidery.[2][3]

Friends practiced plainness in speech by not referring to people in the "fancy" ways that were customary. Often Friends would address high-ranking persons using the familiar forms of "thee" and "thou", instead of the respectful "you". Later, as "thee" and "thou" disappeared from everyday English usage, many Quakers continued to use these words as a form of "plain speech", though the original reason for this usage disappeared, along with "hath". In the twentieth century, "thou hath" disappeared, along with the associated second-person verb forms, so that "thee is" is normal.[4]

Plainness in speech also included affirming rather than making an oath or shaking hands to agree upon a deal, and setting fixed prices for goods rather than bargaining. Early Friends also objected to the names of the days and months in the English language, because many of them referred to Roman or Norse gods, such as Mars (March) and Thor (Thursday), and Roman emperors, such as Julius (July). As a result, the days of the week were known as "First Day" for Sunday, "Second Day" for Monday, and so forth. Similarly, the months of the year were "First Month" for January, "Second Month" for February, and so forth.

Canada Half Year Meeting

Pelham Quarter

Norwich Preparative (later Monthly) Meeting

In 1809 Peter Lossing, a member of the Society of Friends from Dutchess County, New York, visited Norwich Township, and in June, 1810, with his brother-in-law, Peter De Long, purchased 15,000 acres (61 km2) of land in this area. That autumn Lossing brought his family to Upper Canada and early in 1811 settled in Norwich Township. The De Long family and nine others, principally from Dutchess County, joined Lossing the same year and by 1820 an additional group of about fifty had settled within the tract. Many were Quakers and a frame meeting house, planned in 1812, was erected in 1817. These resourceful pioneers founded one of the most successful Quaker communities in Upper Canada.

West Lake Quarter

Adolphustown

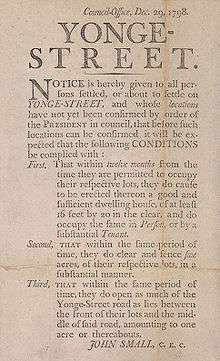

Yonge Street Quarter

In 1801, Timothy Rogers, from Danby Monthly Meeting in Vermont, had travelled up Yonge Street and found a fertile area where he thought he could create a new community that would unite Friends in Canada - until then split between two Yearly Meetings. He applied for and received a grant for land totalling 40 farms, each of 200 acres (0.8 km2), and subsequently returned to Vermont to recruit families to operate those farms. By February 1802, he had set out for King Township with the first group of settlers for those forty farms. A second group followed later that month settling in neighbouring Whitchurch township.

Schisms

The Children of Peace 1812

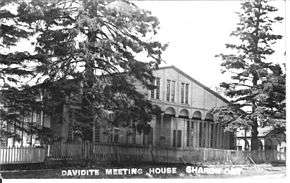

The Children of Peace (1812–1889) were a utopian Quaker sect that separated from the Yonge Street Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends (in what is now Newmarket, Ontario, Canada) during the War of 1812 under the leadership of David Willson. Today, they are primarily remembered for the Sharon Temple, an architectural symbol of their vision of a society based on the values of peace, equality and social justice. Willson said that he was called in a vision to "ornament the Christian Church with the glory of Israel," which he interpreted to mean as abandoning plainness in meeting houses, and in worship.

The group founded the community of Hope (now Sharon) in East Gwillimbury, York Region, Ontario, where they built their Meeting Houses (places of worship) and the Temple. The Temple was constructed between 1825 and 1831. It was constructed in imitation of Solomon's Temple and the New Jerusalem described in Revelation 21, and used once a month to collect alms for the poor; two other meeting houses in the village of "Hope" were used for regular Sunday worship. The Children of Peace, having fled a cruel and uncaring English pharaoh, viewed themselves as the new Israelites lost in the wilderness of Upper Canada; here they would rebuild God’s kingdom on the principle of charity. The village of “Hope” was their new Jerusalem, the focal point of God’s kingdom on earth.

The consolidation of the Children of Peace in Hope was accompanied by their adoption of a cooperative economy. Through cooperative marketing, the establishment of a credit union, and a land-sharing system, the Children of Peace all became prosperous farmers in an era when new farmers frequently failed. The Children of Peace were never communal like many of the other new religious movements then sprouting up in the United States (like the Shakers, the early Mormons or the Oneida Perfectionists).[5] Members of the Children of Peace took a lead role in a similar joint stock company, the Farmers’ Storehouse, Canada’s first farmers’ co-operative.[6]

The Children of Peace played a critical role in the development of democracy in Canada through their support of William Lyon Mackenzie; and by ensuring the elections of both "fathers of responsible government," Robert Baldwin and Louis LaFontaine, despite persistent political violence by the Orange Order.[7]

Hicksite-Orthodox schism 1828

| Divisions of the Religious Society of Friends | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Showing the divisions of Quakers occurring in the 19th and 20h centuries. |

Elias Hicks' religious views, like those of David Willson, were claimed to be universalist and to contradict Quakers' historical orthodox Christian beliefs and practices. His preaching and teaching precipitated the Great Separation of 1827, which resulted in a parallel system of Yearly Meetings in America and Upper Canada. The followers of Hicks were referred to by their opponents as Hicksites. Quakers in Great Britain only recognized the orthodox Quakers and refused to correspond with the Hicksites.

The Hicksite-Orthodox split arose out of both ideologic and socieconomic tension. Hicksites tended to be agrarian and poorer than the more urban, wealthier, Orthodox Quakers. With increasing financial success, Orthodox Quakers wanted to “make the society a more respectable body—to transform their sect into a church—by adopting mainstream Protestant orthodoxy”.[8] Hicksites, though they held a variety of views, generally saw the market economy as corrupting and believed Orthodox Quakers had sacrificed spirituality for material success. Hicksites viewed the Bible as secondary to the individual cultivation of God’s light within.[9] Hicksite beliefs were similar to those of the Children of Peace in their liberalism.

Quakers and the Rebellion of 1837

References

- ↑ Thomas D Hamm on Plainness in The Quakers in America on Google Books.

- ↑ "Quaker Jane" on Plain dress

- ↑ Farnworth One-Name study - article comparing Quakers and Puritans.

- ↑ George Fox, Prescriptivist

- ↑ Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 41–49,115–8.

- ↑ Schrauwers, Albert (2009). Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 97–124.

- ↑ Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 125–149, 211–243.

- ↑ Crothers, Glenn (2012). Quakers Living in the Lion's Mouth: The Society of Friends in Northern Virginia, 1730-1865. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 145.

- ↑ Crothers, Glenn. Quakers Living in the Lion's Mouth. p. 145.