Soteriology

| Part of a series on |

| Salvation |

|---|

|

| General concepts |

| Particular concepts |

| Punishment |

| Reward |

Soteriology (/səˌtɪəriˈɒlədʒi/; Greek: σωτηρία sōtēria "salvation" from σωτήρ sōtēr "savior, preserver" and λόγος logos "study" or "word"[1]) is the study of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special significance in many religions.

In the academic field of religious studies, soteriology is understood by scholars as representing a key theme in a number of different religions and is often studied in a comparative context; that is, comparing various ideas about what salvation is and how it is obtained.

Buddhism

Buddhism is devoted primarily to liberation from suffering, ignorance, and rebirth. The purpose of one's life is to break free from samsara, the cycle of birth-and-pain-and-death, to achieve moksha and nirvana. All types of Buddhism, Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana (or Tantric), tend to emphasize an individual's meditation and liberation, which is to become enlightened.

Theravada Buddhism focuses on the spiritual path outlined in the Pali Canon, with its goal being nibbana, the blowing out of greed, hatred and ignorance. Along this journey, one discovers in experience that they are empty of an unchanging self (anatta). Mahayana Buddhism is the spiritual journey focused on helping others. People who make the pledge to help others before they help themselves are called Bodhisattva. Vajrayana Buddhism is the spiritual journey of transformation, where awareness is transformed into a deity. In all of the three forms of Buddhism, one gradually moves towards liberation, and away from dukkha, and as a result the natural state of Enlightenment becomes the dominant experience in that individual's life.

Buddhist philosophies vary on the subject of the afterlife, but they tend to emphasize an individual's meditation and appeal to the Buddha's teachings, often through an intermediary monk, priest, or teacher who is seen as a "link" (through the direct contacting of an enlightened being) or "helper" in their attaining of 'nirvana'. Amongst other things, nirvana is an ultimate realization that the afterlife is not important, and because of this all fear ends.

All schools of Buddhism teach dependent origination, which points out that the individual is not a separate and isolated entity. This can be directly found using a process of meditation which is the focusing of one's awareness on an object of concentration (samma samadhi). All forms of Buddhism have different ways to realize that the individual is part of a false set of truth-clouding constructs, obscuring 'what is'. The truth of 'what is' is beyond language and must therefore be experienced directly.

Thus, the fundamental reason that the precise identification of these two kinds of clinging to an identity – personal and phenomenal – is considered so important is again soteriological. Through first uncovering our clinging and then working on it, we become able to finally let go of this sole cause for all our afflictions and suffering.[2][3]

In Buddhist thinking, individuals should seek to spread truth and knowledge among all of humanity and strive for the creation of a collective salvation of goodness for all. This is shown in the vow of the bodhisattvas, human beings who have become enlightened through the experience of understanding deep truths:

Never will I seek nor receive private individual salvation– never enter into final peace alone; but forever and everywhere will I live and strive for the universal redemption of every creature throughout all worlds. Until all are delivered, never will I leave the world of sin, sorrow and struggle, but will remain where I am. [4]

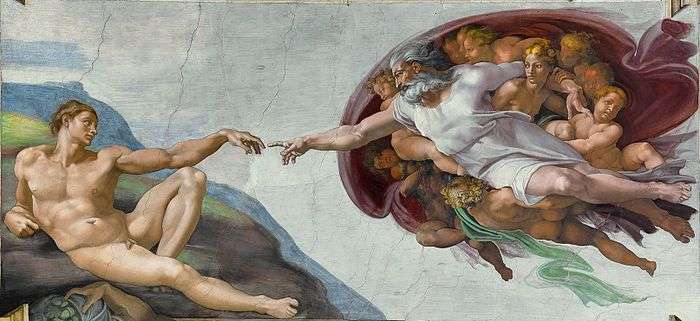

Christianity

In Christianity salvation is the saving of the soul from sin and its consequences.[5] It may also be called "deliverance" or "redemption" from sin and its effects.[6]

Variant views on salvation are among the main fault lines dividing the various Christian denominations, both between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism and within Protestantism, notably in the Calvinist–Arminian debate, and the fault lines include conflicting definitions of depravity, predestination, atonement, and most pointedly, justification.

According to Christian belief, salvation is made possible by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, which in the context of salvation is referred to as the "atonement".[7] Christian soteriology ranges from exclusive salvation[8]:p.123 to universal reconciliation[9] concepts. While some of the differences are as widespread as Christianity itself, the overwhelming majority agrees that salvation is made possible only by the work of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, dying on the cross and being resurrected from death.

Hinduism

In Vedic religion (Hinduism), individual salvation is not, as is often incorrectly alleged, pursued to the neglect of collective well-being. "The principle on which the Vedic religion is founded," observes the Sage of Kanchi, "is that a man must not live for himself alone but serve all mankind." Varna dharma in its true form is a system according to which the collective welfare of society is ensured. Hinduism, which teaches that we are caught in a cycle of death and rebirth called saṃsāra, contains a slightly different sort of soteriology, as noted above, devoted to the attainment of transcendent moksha (liberation). For some, this liberation is also seen as a state of closeness to Brahman.

Westerners coined the name "Hinduism" itself as a convenience to encompass a constellation of different paths to moksha, based upon the Vedas, India's original religious texts.[10] “In India,” wrote Mircea Eliade, “metaphysical knowledge always has a soteriological purpose.” [11]

Islam

Islamic soteriology focuses on how humans can repent of and atone for their sins so as not to occupy a state of loss. Muslims believe that everyone is responsible for his own action. So even though Muslims believe that Adam and Hawwa, the parents of humanity, committed a sin by eating from the forbidden tree and thus disobeying God, they believe that humankind is not responsible for such an action. They believe that God is fair and just and requested forgiveness from him to avoid being punished for not doing what God asked of them and listening to Satan.[12]

Muslims believe that they, as well as everyone else, are vulnerable to making mistakes and thus they need to seek repentance repeatedly at all times. Muhammad said "By Allah (God), I seek the forgiveness of Allah and I turn to Him in repentance more than seventy times each day." (Narrated by al-Bukhaari, no. 6307)

Not only that God wants his servants to repent and forgives them, he rejoices over it, as Muhammad said "When a person repents, Allaah rejoices more than one of you who found his camel after he lost it in the desert." (Agreed upon. Narrated by al-Bukhaari, no. 6309)

Islamic tradition has generally held that the vast majority of humanity shall receive punishment in hell upon death and that only a small few will enter paradise. For example, the Hadith, as recounted in the Sahih al-Bukhari, decrees that out of every one thousand people entering into the afterlife that nine hundred and ninety-nine of them will end up in the fire of despair.[13]

Jainism

Mokṣa in Jainism means liberation, salvation, or emancipation of soul. It is a blissful state of existence of a soul, completely free from the karmic bondage, free from saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death. A liberated soul is said to have attained its true and pristine nature of infinite bliss, infinite knowledge, and infinite perception. Such a soul is called siddha or paramatman and considered as supreme soul or God. In Jainism, it is the highest and the noblest objective that a soul should strive to achieve. In fact, it is the only objective that a person should have; other objectives are contrary to the true nature of soul.

Judaism

In contemporary Judaism, redemption (Hebrew ge'ulah), refers to God redeeming the people of Israel from their various exiles.[14] This includes the final redemption from the present exile.[15]

Judaism holds that adherents do not need personal salvation as Christians believe. Jews do not subscribe to the doctrine of Original sin.[16] Instead, they place a high value on individual morality as defined in the law of God — embodied in what Jews know as the Torah or The Law, given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai, the summary of which is comprised in the Ten Commandments. The Jewish sage Hillel the Elder states that The Law can be further compressed in just one line, popularly known as the Golden Rule: "That which is hateful to you, do not do unto your fellow".[17]

In Judaism, salvation is closely related to the idea of redemption, a saving from the states or circumstances that destroy the value of human existence. God as the universal spirit and Creator of the World, is the source of all salvation for humanity, provided an individual honours God by observing his precepts. So redemption or salvation depends on the individual. Judaism stresses that salvation cannot be obtained through anyone else or by just invoking a deity or believing in any outside power or influence.[17]

Some sections of Jewish religious texts appear to argue that no afterlife exists even for the good and just, with the Book of Ecclesiastes telling the faithful: "The dead know nothing. They have no reward and even the memory of them are lost."[18] Rabbis and Jewish laypeople have often wrestled with such passages for many centuries.

Mystery religions

In the mystery religions, salvation was less worldly and communal, and more a mystical belief concerned with the continued survival of the individual soul after death.[19] Some savior gods associated with this theme are dying-and-rising gods, often associated with the seasonal cycle, such as Osiris, Tammus, Adonis, and Dionysus. A complex of soteriological beliefs was also a feature of the cult of Cybele and Attis.[20]

The similarity of themes and archetypes to religions found in antiquity to later Christianity has been pointed out by many authors, including the Fathers of the early Christian church. One view is that early Christianity borrowed these myths and motifs from contemporary Hellenistic mystery religions, which possessed ideas such as life-death-rebirth deities and sexual relations between gods and human beings. While Christ myth theory is not accepted by mainstream historians, proponents attempt to establish causal connections to the cults of Mithras, Dionysus, and Osiris among others.[21]

Sikhism

Sikhism advocates the pursuit of salvation through disciplined, personal meditation on the name and message of God, meant to bring one into union with God. But a person's state of mind has to be detached from this world, with the understanding that this world is a temporary abode and their soul has to remain untouched by pain, pleasure, greed, emotional attachment, praise, slander and above all, egotistical pride. Thus their thoughts and deeds become "Nirmal" or pure and they merge with God or attain "Union with God", just as a drop of water falling from the skies merges with the ocean.

Other religions

Shinto and Tenrikyo similarly emphasize working for a good life by cultivating virtue or virtuous behavior.

See also

References

- ↑ "soteriology", definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary which erroneously gives neuter nominative of the corresponding adjective, σωτήριον, as the base.

- ↑ Karl Brunnholzl page 131 of his book "The Center of the Sunlet Sky, Madhyamaka in the Kagyu Tradition"

- ↑ http://www.vipassana.com/resources/8fp7.php

- ↑ "The Great Divorce by C.S. Lewis". Patheos.com - Daylight Atheism. Retrieved July 2, 2014. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "The saving of the soul; the deliverance from sin and its consequences" OED 2nd ed. 1989.

- ↑ Wilfred Graves, Jr., In Pursuit of Wholeness: Experiencing God's Salvation for the Total Person (Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image, 2011), 9, 22, 74-5.

- ↑ "Christian Doctrines of Salvation." Religion facts. June 20, 2009. http://www.religionfacts.com/christianity/beliefs/salvation.htm

- ↑ Newman, Jay. Foundations of religious tolerance. University of Toronto Press, 1982. ISBN 0-8020-5591-5

- ↑ Parry, Robin A. Universal salvation? The Current Debate. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-8028-2764-0

- ↑ David S. Noss. A History of the World's Religions.

- ↑ Mircea Eliade. Yoga: Immortality and Freedom.

- ↑ In Az-Zumar (The Groups) chapter, in verse 7, in the Qur'an, God said "No bearer of Burdens shall bear the burden of another" [39:7]. So repentance in Islam is to be forgiven from the poor decisions sent forth by one's own hand. In Islam, for one to repent, s/he has to admit to their Lord that they were disobedient, feel regret for their behavior, be willing not to do the same again and finally to ask for repentance through prayer. S/he does not need to go to speak to someone to deserve the repentance, simply during the prayer, s/he speaks to her/his God (prays) asking His forgiveness. God said in the Qur'an "O you who believe! Turn to Allah (God) with sincere repentance! It may be that your Lord will expiate from you your misdeeds, and admit you into Gardens under which rivers flow (Paradise)". al-Tahreem 66:8 Muslims believe that God is merciful and thus believers are expected to continuously seek forgiveness so that their misdeeds may be forgiven. "Say: O my servants who have transgressed against themselves (by committing evil deeds) Despair not of the Mercy of Allah (God), verily, Allah forgives all. Truly, He is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful” al-Zumar 39:53 and also "And whoever does evil or wrongs himself but afterwards seeks Allaah’s forgiveness, he will find Allaah Oft Forgiving, Most Merciful" al-Nisaa 4:110.

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari Volume 4, Book 55, Hadith number 567.

- ↑ "Reb on the Web". Kolel: The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Salvation, Judaism. Accessed 4 May 2013

- ↑ "How Does a Jew Attain Salvation?" Accessed: 4 May 2013

- 1 2 Malekar, Ezekiel Isaac. "THE SPEAKING TREE: Concept of Salvation In Judaism". The Times of India. Accessed: 4 May 2013

- ↑ Ecclesiastes 9:5

- ↑ Pagan Theologies: Soteriology

- ↑ Giulia Sfameni Gasparro. Soteriology and mystic aspects in the cult of Cybele and Attis.

- ↑ Pagan Origins of the Christ Myth

Further reading

- John McIntyre, Shape of Soteriology: Studies in the Doctrine of the Death of Christ (T&T Clark, 1992)