Manchán of Lemanaghan

Saint Manchán mac Silláin (died 664), Manchianus in Latin sources, is the name of an early Irish saint, patron of Liath Mancháin, now Lemanaghan, in County Offaly.[1][2] He is not to be confused with the scholar Manchán or Manchéne, abbot of Min Droichit (Co. Offaly).[2] There are variant traditions concerning the saint's pedigree, possibly owing to confusion with one of several churchmen named Manchán or Mainchín.[2] The most reliable genealogy makes him a son of Sillán son of Conall, who is said be a descendant of Rudraige Mór of Ulster, and names his mother Mella.[2]

Foundation of the monastery

| Dúthracar, a Maic Dé bí, | "I wish, O son of the living God, |

| a Rí suthain sen, | eternal ancient King, |

| bothán deirrit díthraba | for a hidden little hut in the wilderness |

| command sí mo threb, | that it might be my dwelling," |

| (First stanza of an anonymous | poem ascribed to St Manchán)[3] |

Manchán's church, Liath Mancháin, was located in the kingdom of Delbnae Bethra[1] and its remains now lie approximately two kilometres from Pollagh. The foundation was never able to compete with that of St Ciarán at Clonmacnoise, to the west of Lemanaghan.[1]

Manchán is said to have founded his monastery in c. 645 AD after being provided land by Ciarán. In 644, Diarmuid, high king of Ireland, stopped at Clonmacnoise while on his way to battle Guaire, the king of Connacht. There he asked for the monk's prayer and when he emerged from battle victorious Diarmuid granted St. Ciarán the land of "the island in the bog," now known as Leamonaghan. The only condition was that St. Ciarán was to send one of his monks to Christianize the land, that being St. Manchán. St. Manchán went forward in converting the people and established a monastery.

About 500 meters from the monastery is a small stone house built by Manchán for his mother Mella. The structure is known locally as Kell and the ruins of the house can still be visited today. Legend says that one day the saint was thirsty and the monastery was absent of water. Upon striking a rock a spring well bubbled up, and the area is now known as St. Manahan's well. It's been visited by people from all over the world, commonly on 24 January every year. It is said that many people have been cured of diseases after visiting the well. The saint is also credited with writing a poem in Gaelic, that describes the desire of Ireland's martyrs. He died from the yellow plague in 664. He was known for his generous nature, wisdom and his knowledge of sacred scripture.

An Old or Middle Irish nature poem described as a comad and beginning "I wish, O Son of the living God ... a hidden little hut in the wilderness" is attributed to him. The language has been variously dated to the late 8th or early 9th century,[2] or even the tenth.[4]

Death and veneration

Several sources, notably Irish annals, relate that Manchán was one of the churchmen to meet in 664 for a communal prayer and fast to God, in which they insisted that God would send a plague on Ireland. The purpose was to bring death to a large segment of the lower classes of the Irish population (see also Féchín of Fore). Manchán was one of the saints to die in the event.[2] According to the Irish martyrologies, his feast day is commemorated on 20 January.[1][2] What remains of Manchán's foundation at Lemanaghan are monastic ruins and a graveyard.[1]

St. Manchán's shrine

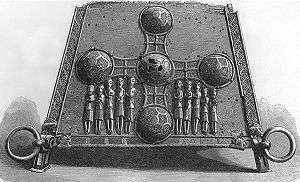

Perhaps St. Manchán is best known for the shrine containing his relics, now preserved in the Catholic Church at Boher, County Offaly. The shrine was created in 1130 at Clonmacnoise and still contains some of the saint's remains. It is considered a masterpiece of Romanesque metalwork.[5]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stalmans and Charles-Edwards, "Meath, saints of (act. c.400–c.900)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Breen, "Manchán, Manchianus, Manchíne". Dictionary of Irish Biography.

- ↑ Edited and translated by Gerard Murphy

- ↑ Murphy, "Manchán's Wish", pp. 184–5.

- ↑ Harbison, Potterton, Sheehy. Irish Art and Architecture, p. 55.

References

Primary sources

- Irish annals:

- Irish martyrologies:

- Félire Óengusso

- Martyrology of Tallaght

- Martyrology of Gorman

- Martyrology of Donegal

- Anonymous poem beginning Duthracar, a Maic Dé bí ("I wish, O Son of the living God"), preserved in a 16th-century MS, RIA MS 23 N 10, p. 95.

- Murphy, Gerard (ed. and tr.) (1998) [1956]. "Manchán's Wish". Early Irish Lyrics. pp. 29–31.

- Jackson, Kenneth Hurlstone. Early Celtic Nature Poetry. pp. 4–5.

- Meyer, Kuno (ed. and tr.) (1904). "Comad Manchín Léith". Ériu. 1.

Secondary sources

- Breen, Aidan (2010). "Manchán, Manchianus, Manchíne". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Graves, James (1874). "The Church and Shrine of St. Manchán". The Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland. 3: 134–50.

- Harbison, Peter, H. Potterton, J. Sheehy, eds. (1978). Irish Art and Architecture: From Prehistory to the Present. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Stalmans, Nathalie and T.M. Charles-Edwards (September 2004). "Meath, saints of (act. c.400–c.900)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition, May 2007 ed.). Oxford University Press. Accessed: 14 December 2008

Further reading

- Corkery, John (1970). Saint Manchan and his Shrine. Longford.

- De Paor, Liam (1998). "The Monastic ideal; a poem attributed to St. Manchán". In Liam de Paor. Ireland and Early Europe: Essays and occasional writings on art and culture. Dublin. pp. 163–9. ISBN 1-85182-298-4.

- Meyer, Kuno (1904). "Comad Manchín Léith". Ériu. 1.