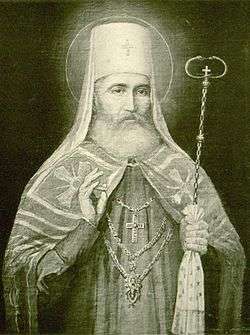

Petar I Petrović Njegoš

| Petar I Petrović Njegoš | |

|---|---|

| Prince-Bishop of Montenegro | |

| |

| Native name | Петар I |

| Installed | 1784 |

| Term ended | 1830 |

| Predecessor | Arsenije Plamenac |

| Successor | Peter II |

| Orders | |

| Ordination |

1784 by Mojsije Putnik |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1748 Njeguši, Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro, Ottoman Empire |

| Died |

October 31, 1830 (aged 82) Cetinje, Montenegro |

| Denomination | Serbian Orthodox Christian |

| Residence | Cetinje |

| Parents | Marko Petrović and Anđelija Martinović |

| Coat of arms |

|

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | October 31 (Gregorian calendar), October 18 (Julian calendar) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Title as Saint | Saint Peter of Cetinje |

| Canonized | by Serbian Orthodox Church |

Petar I Petrović Njegoš (Serbian Cyrillic: Петар I Петровић Његош; 1748 – 31 October 1830) was the ruler of the Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro as the Metropolitan (vladika) of Cetinje, and Exarch (legate) of the Serbian Orthodox Church throne. He was the most popular spiritual and military leader from the Petrović dynasty. During his long rule, Petar strengthened the state by uniting the often quarreling tribes, consolidating his control over Montenegrin lands, introducing the first laws in Montenegro (Zakonik Petra I) and a program of liberation and unification of Serbs. His rule prepared Montenegro for the subsequent introduction of modern institutions of the state: taxes, schools and larger commercial enterprises. He was canonized by the Serbian Orthodox Church as "St. Peter of Cetinje" (Свети Петар Цетињски).

He was described as "a man of uncommon size, handsome features, considerable talent, and a highly respected character" by Therese Albertine Luise Robinson.[1]

Early life

The son of Marko and Anđelija (née Martinović), Petar followed the footsteps of his relatives, becoming a monk and a deacon. He spent four years in Imperial Russia, finishing the Military School (1765–69). Chosen ahead as a future metropolitan by Vasilije Petrović, he had strong support among the tribal chieftains. Sava Petrović (s. 1735–1781) appointed his nephew and co-adjutor Arsenije Plamenac[2] the successor, which was met with opposition from the Montenegrin tribes at the beginning, later switching in favour after Sava gained the support of Šćepan Mali.[3] Plamenac served between 1781 and 1784.[3]

Office

1784–99

He was made a bishop (ordained) by Mojsije Putnik of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci at Sremski Karlovci on 13 October 1784. During his long trip to Russia that year and the following (1785), Montenegro was attacked by Ottoman forces. When the large army of Kara Mahmud Pasha, the Pasha of Scutari, advanced towards Montenegro, the Montenegrin army of 8,000 was reduced by 3,000 Crmničani, and they were followed by many more surrenders.[4] Mahmud Pasha crossed Bjelice, and burnt down Njeguši, and received help from Nikšići, then crossed Paštrovići to return to Scutari.[5] When Petar I returned from Russia, he planned for counter-attack and expansion.

The Metropolitan Petar I and guvernadur Jovan Radonjić were the two head chiefs of Montenegro, one by title, the other according to actual position.[6] Jovan sought to rule Montenegro by himself; he appropriated secular rights for himself, and wanted the Metropolitan to exerice only his spiritual leadership;[7] that the guvernadur was the master of the people and the Metropolitan the master of the church.[8] The two clashed in international politics: the Metropolitan held to Russia, while Jovan relied on Austria.[7][9] Hence, there were two parties in the land, one "Russophile" and the other "Austrophile", led by the Metropolitan and Jovan, respectively.[7] On the question whether to support Austria or not, the two sides conflicted during the Austro-Turkish War (1787–91) and Russo-Turkish War (1787–92).[10] During this period, Montenegro was divided into the following districts: Katunska nahija, Riječka nahija, Crmnička nahija, Lješanska nahija and Pješivačka nahija. These were governed by the officials, Jovan Radonjić and the Metropolitan, with the help of 5 serdars, 9 vojvodas and 34 knezes (a synthesis of secular and theocratic government which will cause strife and struggle for supremacy until 1832–33).[11]

In July 1788, Jovan Radonjić asked Queen Catherine II to send Sofronije Jugović,[12] whom he promised the throne of Montenegro; Jovan sought to bring him to the land and replace Petrović, then get rid of him too, securing the rule for himself.[13] He sent another letter in 1789,[12] then made a trip to Austria[14] seeking to retrieve his reputation with the help of the Austrian court.[14] Radonjić requested that the Austrian army be sent into Montenegro, which was declined.[14] On Radonjić's re-request, the Austrian Emperor decided to send munition to Montenegro in February 1790, provided that the Montenegrins "come under the wings of the Emperor in war-time, as much as in peace-time, with the Ottoman Empire".[14] Austrian support looked unpromising.[14]

In 1794, the Kuči and Rovčani (tribes outside Montenegro) were devastated by the Ottomans.[15] In 1796, Kara Mahmud Pasha was defeated at the Battle of Martinići. Mahmud Pasha later returned and was defeated and killed at the Battle of Krusi on 22 September. Half of the Montenegrin army was led by Metropolitan Petar I, the other by Jovan.[16] Petar I's army was assisted by the Piperi.[15] Mahmud Pasha's army, allegedly made up of 30,000, including seven French officers, fought a Montenegrin force of 6,000, and had heavy casualties. The Montenegrin victory resulted in territorial expansion, with the tribes of Bjelopavlići and Piperi being joined into the Montenegrin state.[17] The Rovčani, as other highlander tribes, subsequently turned more and more towards Montenegro.[18] Metropolitan Petar I sent letters in 1799 to the Moračani and Rovčani, advising them to live peacefully and in solidarity.[18] In 1799, Montenegro was guaranteed a subsidy by Russia, which assured that it would defend its interest.[19]

1800–09

During the First Serbian Uprising Petar I began cooperating with Karađorđe, the Serbian rebel leader. Petar I had by that time distinguished himself in international relations, as the bishop and ruler of Montenegro. It was known that Petar was ready to revolt as soon as a favourable opportunity came along. Russian ambassador in Vienna, Razumovski, informed Interior Minister Czartoryski of a secret message received on 13 December 1803 that Petar I had 2,000 armed men, and that he "had taken off his bishop clothes and dressed in military clothing, a general uniform" and that he planned to raise his army to 12,000 men. Knowing that his army would not be able to fight the stronger Ottomans, he sought to unite with the "rebels of Šumadija", and together, with the help of the Russian, turn on the Turks. He messaged Visoki Dečani of his intentions.[20] Petar I was a pen pal of Dositej Obradović.[21]

In 1806, the troops of Napoleonic France advanced toward the Bay of Kotor in Montenegro. The Montenegrin army led by Petar I, aided by several Russian battalions and the fleet of Admiral Dmitry Senyavin pushed them back to Dubrovnik. But soon after, Russian Tsar Alexander I asked Montenegrins to relinquish control of Boka to Austria. However, after Montenegrins retreated to Herceg Novi, Alexander changed his mind again, and with a help of Montenegrins conquered Brač and Korčula. In the meantime, France encouraged Turkey to attack Russia, which withdrew its fleet from the Adriatic to defend the Ionian islands. The Treaty of Tilsit (1807) between Russia and France granted the control of the Bay of Kotor to France. In early 1807, Petar had plans to unite several Serb-inhabited regions into a renewed Serbian Empire. In February 1807, Petar I planned an invasion of Herzegovina and asked for Karađorđe's aid.[19] After the Battle of Suvodol and Serbian rebel advance, Karađorđe managed connecting the rebel forces to Montenegro (1809).[22] However, Karađorđe was unable to hold lasting ties with the Serbs of Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as after 1809 the uprising waned.[23]

1810–20

Petar I waged a successful campaign against the Bosnia Eyalet in 1819. In 1820, in the north of Montenegro, the highlanders from Morača led by serdar Mrkoje Mijušković won a major battle against the Ottoman Bosnian forces. The repulse of an Ottoman invasion from Albania during the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29) led to the recognition of Montenegrin sovereignty over Piperi.[24] Petar I had managed to unite the Piperi and Bjelopavlići with Montenegro,[24] and when Bjelopavlići and the rest of the Hills (Seven hills) were joined into the Montenegrin state, the polity was officially called "Black Mountain (Montenegro) and the Hills".[25]

Pan-Serbism

Petar I conceived a plan in 1807 to revive a Serbian Empire ("Slaveno–Serb empire"), which he informed the Russian court.[26][27][28][29] Earlier, in June 1804, Habsburg Serb metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović informed the Russian court of the same plan.[30] Petar I's plan was to unite Podgorica, Spuž, Žabljak, the Bay of Kotor, Herzegovina, Dubrovnik and Dalmatia with Montenegro.[26] The title of Serbian emperor would be held by the Russian emperor.[26] The French–Russian peace treaty thwarted the plan.[26] After the French conquered Dalmatia, they offered Petar I the title of "Patriarch of all of the Serb nation or all Illyricum" under the condition that he stop cooperation with Russia and accept a French protectorate, which he declined, fearing eventual Papal jurisdiction.[27] The Metropolitanate of Cetinje began exerting influence towards Brda and Old Herzegovina, which considered Montenegro as the leader for liberation.[27] While his reputation and influence reached the surrounding lands, he increasingly directed himself to Revolutionary Serbia as the backbone for liberation and unification.[27] The project is included in several historiographical works.

Canonisation

He was canonised as Saint Peter of Cetinje by his successor Petar II Petrović Njegoš. The Serbian Orthodox Church celebrates him on October 31, Gregorian calendar, which is October 18 in the Julian calendar.

Works

- The Lore in Verse (Поучење у стиховима)

- The Sons of Ivan-bey (Синови Иванбегови)

- Poem to Karageorge (Пјесма Карађорђу)

- To Serb Christmas Eve (Српско Бадњи вече)

References

- ↑ Talvj. Historical View of the Language and Literature of the Slavic Nations: With a Sketch of Their Popular Poetry. G.P. Putnam. pp. 120–.

- ↑ Kostić 2000, p. 351.

- 1 2 Journal of Central European Affairs. 1959. p. 81.

- ↑ Srbsko Učeno Društvo 1891, p. 262.

- ↑ Rade Turov Plamenac; Jovan R. Bojović (1997). Memoari. CID. p. 537.

- ↑ Red. za istoriju Črne Gore 1975, p. 460

Петровић и гувернадур Јован Радоњић, два прва црногорска главара, један по звању, а други по стварном положају. У почетку сложни, они се ускоро размимоилазе, јер сваки од супарника настоји да обезбиједи првенство у ...

- 1 2 3 Brastvo. 32. Društvo sv. Save. 1941. p. 91.

Гувернадур Јоко је хтео да потпуно завлада земљом; он је себи присвајао право световне, а владику је хтео да ограничи на вршење духовне власти. У спољној политици се такође нису слагали: владика је држао с Русијом, док се гувернадур ослањао на Аустрију. Отуда су у земљи и постојале две странке: русо- филска и аустрофилска; прву је водио владика, а другу гувернадур ...

- ↑ Srbsko Učeno Društvo 1891, p. 227.

- ↑ Red. za istoriju Črne Gore 1975, p. 460.

- ↑ Čubrilović 1983, p. 362

На питању за Аустрију или против Аустрије сукобили су се у руско-аустријском рату против Турске 1787 — 1792. владика Петар I и гувернадур Јоко Радоњић. Организујући отпор против аустријског утицаја у својој земљи за ...

- ↑ Историски записи. 73. с.н. 2000. p. 127.

Њима су управљали гувернадур Иван Радоњић и митрополит помоћу 5 сердара, 9 војвода и 34 кнеза (синтеза световне и теократске власти, што ће изазивати трвења и борбу за примат све до 1832-1833. године)

- 1 2 Vasilije Derić (1900). O srpskom imenu po zapadnijem krajevima našega naroda. Štampano u državnoj štampariji.

1788. год. пише Иван Радоњић, црногорски губернатор, руској царици Катарини II.: „Сада ми сви Срби Црногорци молимо вашу царску милост да пошљете к нама књаза Софронија Југовића“." 1789. год. пише опет Иван Радоњић, црногорски губернатор, руској царици: „Сад ми сви Срби из Црне Горе, Херцеговине, Бањана, Дробњака, Куча, Пипера, Бjeлопавлића, Зете, Климената, Васојевића, Братоножића, Пећи, Косова, Призрена, Арбаније, Маћедоније припадамо вашему величанству и молимо, да као милостива наша мајка пошљете к нама књаза Со- фронија Југовића

- ↑ Srbsko Učeno Društvo 1891, p. 228.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Red. za istoriju Črne Gore 1975, p. 442

- 1 2 Barjaktarović 1984, p. 28

- ↑ Novak 1949, p. 178

... под Мартинићима и 22 септембра исте године у Крусима, недалеко Под- горице, половином црногорске војске командовао владика Петар I, а другом половином гувернадур Јоко. Из овога се јасно види до које висине је доспела ...

- ↑ Ferdo Čulinović (1954). Državnopravna historija jugoslavenskih zemalja XIX i XX vijeka: knj. Srbija, Crna Gora, Makedonija, Jugoslavija, 1918-1945. Školska knjiga.

- 1 2 Barjaktarović 1984, p. 29

- 1 2 Király & Rothenberg 1982, p. 65.

- ↑ Bogunović.

- ↑ Dositej Obradović (1899). Domaća pisma. Srpska književna zadruga. p. 203.

- ↑ Morison, W. A. (1942). The Revolt of the Serbs Against the Turks 1804-1913. Cambridge University Press. GGKEY:BRSF4PUC0LU.

- ↑ David MacKenzie (1967). The Serbs and Russian Pan-Slavism, 1875-1878. Cornell University Press. p. 4.

- 1 2 Miller 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ Etnografski institut (Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti) (1952). Posebna izdanja, Volumes 4-8. Naučno delo. p. 101.

Када, за владе Петра I, црногорсксу држави приступе Б^елопавлиЬи, па после и остала Брда, онда je, званично, „Црна Гора и Брда"

- 1 2 3 4 Јован Милићевић (1994). "Петар I Петровић, Идеја о обнови српске државе". Црна Гора 1797-1851. Историјa српског народа, V-1. Београд. pp. 170–171.

- 1 2 3 4 Ослобођење, независност и уједињење Србије и Црне Горе. Београд: Историјски музеј Србије. 1999. p. 116.

- ↑ Bulletin scientifique. 22-23. Le Conseil. 1986. p. 300.

This was the time when Petar I devised his visionary programme of creation of a Slavonic- -Serbian state

- ↑ Soviet Studies in History. 20. International Arts and Sciences Press. 1982. p. 28.

Montenegro sent to Russia in the spring of 1807 a project for establishing a Slavic-Serbian kingdom in the Balkans

- ↑ Петар И Поповић (1933). Француско-српски односи за време првог устанка: Наполеон и Карађорђе. Издање потпомогнуто је из на Задужбине Луке Ћеловића-Требињца. p. 10.

Sources

- Király, Béla K.; Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1982). War and Society in East Central Europe: The first Serbian uprising 1804-1813. Brooklyn College Press. ISBN 978-0-930888-15-2.

- Miller, William (2012). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors 1801-1927. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-26046-9.

- Milović, Jevto M. (1987). Petar I Petrović Njegoš: pisma i drugi dokumenti. Istorijski institut SR Crne Gore.

- Pavićević, Branko (2007). Petar I Petrović Njegoš. CID.

- Bogunović, Nebojša. Iz srpske istorije. eBook Portal. pp. 71–74. GGKEY:TEEA3BSLU7B.

- Вуксан Душан (1951). Петар I Петровић Његош и његово доба. Цетиње.

- Kostić, Lazo M. (2000). Његош и српство. Српска радикална странка. ISBN 978-86-7402-035-7.

- Stamatović, Aleksandar (1999). "Митрополија црногорска за вријеме митрополита Петровића". Кратка историја Митрополије Црногорско-приморске (1219-1999).

- Dragoslav Srejović; Slavko Gavrilović; Sima M. Ćirković (1981). Istorija srpskog naroda. 5. Srpska književna zadruga.

- Čubrilović, Vasa (1983). Odabrani istorijski radovi. Narodna knjiga.

- Novak, Viktor (1949). Istoriski časopis. 1.

- Red. za istoriju Črne Gore (1975). Istorija Črne Gore: Od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Red. za istoriju Črne Gore.

- Glasnik cetinjskih muzeja (1974). Glasnik cetinjskih muzeja. 7–10.

- Srbsko Učeno Društvo (1891). Glasnik Srbskog učenog društva. 72. u Državnoj štampariji.

External links

- Свети Петар Цетињски: Житије, дјело, молитва

- Speeches to Montenegrins before battles against Turks on Martinici and on Krusi, 1796

- of Petar I

- "Идеја светог Петра Цетињског о обнови српске државе / План цетињског митрополита (владике) Петра I Петровића о формирању славено-сербскога царства 1807.". Njegos.org.

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arsenije Plamenac |

Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Hills 1784–1830 |

Succeeded by Petar II |