Startling Stories

Startling Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1955 by publisher Ned Pines' Standard Magazines. It was initially edited by Mort Weisinger, who was also the editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories, Standard's other science fiction title. Startling ran a lead novel in every issue; the first was The Black Flame by Stanley G. Weinbaum. When Standard Magazines acquired Thrilling Wonder in 1936, it also gained the rights to stories published in that magazine's predecessor, Wonder Stories, and selections from this early material were reprinted in Startling as "Hall of Fame" stories. Under Weisinger the magazine focused on younger readers and, when Weisinger was replaced by Oscar J. Friend in 1941, the magazine became even more juvenile in focus, with clichéd cover art and letters answered by a "Sergeant Saturn". Friend was replaced by Sam Merwin, Jr. in 1945, and Merwin was able to improve the quality of the fiction substantially, publishing Arthur C. Clarke's Against the Fall of Night, and several other well-received stories.

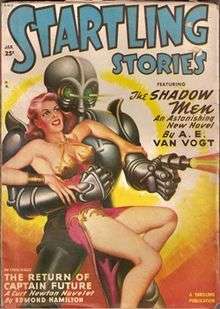

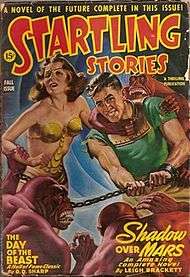

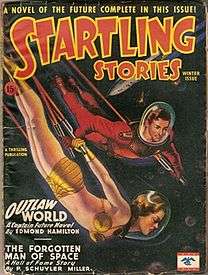

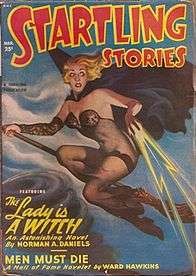

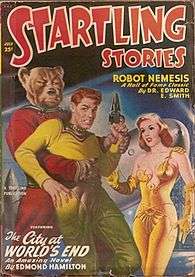

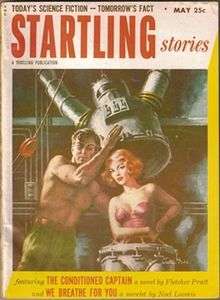

Much of Startling's cover art was painted by Earle K. Bergey, who became strongly associated with the magazine, painting almost every cover between 1940 and 1952. He was known for equipping his heroines with brass bras and implausible costumes, and the public image of science fiction in his day was partly created by his work for Startling and other magazines. Merwin left in 1951, and Samuel Mines took over; the standard remained fairly high but competition from new and better-paying markets such as Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction impaired Mines' ability to acquire quality material. In mid-1952, Standard attempted to change Startling's image by adopting a more sober title typeface and reducing the sensationalism of the covers, but by 1955 the pulp magazine market was collapsing. Startling absorbed its two companion magazines, Thrilling Wonder and Fantastic Story Magazine, in early 1955, but by the end of that year it too ceased publication.

Ron Hanna of Wild Cat Books revived Startling Stories in 2007.[1]

Publication history

Although science fiction had been published before the 1920s, it did not begin to coalesce into a separately marketed genre until the appearance in 1926 of Amazing Stories, a pulp magazine published by Hugo Gernsback. By the end of the 1930s the field was booming.[2] Standard Magazines, a pulp publishing company owned by Ned Pines, acquired its first science fiction magazine, Thrilling Wonder Stories, from Gernsback in 1936.[3] Mort Weisinger, the editor of Thrilling Wonder, printed an editorial in February 1938 asking readers for suggestions for a companion magazine. Response was positive, and the new magazine, titled Startling Stories, was duly launched, with a first issue (pulp-sized, rather than bedsheet-sized, as many readers had requested), dated January 1939.[4] Initial pay rates were half a cent per word, lower than the leading magazines of the day.[5][6]

Startling was launched on a bimonthly schedule, alternating months with Thrilling Wonder Stories, though in 1940 Thrilling moved to a monthly schedule that lasted for over a year.[7][8] The first editor was Mort Weisinger, who had been an active fan in the early 1930s and had joined Standard Magazines in 1935, editing Thrilling Wonder from 1936.[9] Weisinger left in 1941 to take a new post as editor of Superman, and was replaced by Oscar J. Friend, who was an established writer of pulp fiction, though his experience was in western fiction rather than sf.[10][11][12] During Friend's tenure Startling slipped from bimonthly to quarterly publication. Friend lasted for a little over two years, and was replaced by Sam Merwin, Jr., as of the Winter 1945 issue.[13]

Merwin succeeded in making Startling popular and successful, and the bimonthly schedule was resumed in 1947.[13][14] At the start of 1952 Startling switched to a monthly schedule; this was unusual in that Startling was notionally junior to Thrilling Wonder, its sister magazine, which remained bimonthly.[15][note 1] Merwin left shortly before this switch, in order to spend more time on his own writing. He was replaced by Samuel Mines, who had worked with Standard's Western magazines, though he was a science fiction aficionado.[16]

Street & Smith, one of the longest established and most respected publishers, shut down all of their pulp magazines in the summer of 1949. The pulps were dying, partially as a result of the success of paperbacks. Standard continued with Startling and Thrilling, but the end came only a few years later.[17] In 1954, Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a book in which he asserted that comics were inciting children to violence. A subsequent Senate subcommittee hearing led to a backlash against comics, and the publishers dropped titles in response. The financial impact spread to pulp magazines, since often a publisher would publish both. A 1955 strike by American News Corporation, the main distributor in the U.S., meant that magazines remained in warehouses and never made it to the newsstands; the unsold copies represented a significant financial blow and contributed to publishers' decisions to cancel magazines. Startling was one of the casualties. The schedule had already returned from monthly to bimonthly in 1953, and it became a quarterly in early 1954. Thrilling Wonder published its last issue in early 1955, and was then merged with Startling, as was Fantastic Story Magazine, another companion publication, but the combined magazine only lasted three more issues.[7][14][18] Mines left the magazine at the end of 1954; he was succeeded for two issues by Theron Raines, who was followed by Herbert D. Kastle for the last two. The final issue was dated Fall 1955.[14][note 2]

Contents and reception

War years

From the beginning, every issue of Startling contained a complete novel, along with one or two short stories; long stories did not appear since the publisher's policy was to avoid serials.[4][22] When Standard Magazines had bought Wonder Stories in 1936, they had also acquired rights to reprint the stories that had appeared in it and in its predecessor magazines, Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories, and so Startling also included a "Hall of Fame" reprint from one of these magazines in every issue.[7] The first lead novel was The Black Flame, a revised version of "Dawn of Flame", a story by Stanley Weinbaum that had previously appeared only in an edition limited to 250 copies. There was also a tribute to Weinbaum, written by Otto Binder; Weinbaum had died in 1935 and was well regarded, so even though the story was not one of his best, it was excellent publicity for the magazine. Otto and his brother, Earl, also contributed a story, "Science Island", under their joint pseudonym Eando Binder. The "Hall of Fame" reprint was D.D. Sharp's "The Eternal Man", from 1929. Other features included a pictorial article on Albert Einstein, and a set of biographical sketches of scientists, titled "Thrills in Science".[4] The letter column was called "The Ether Vibrates", and there was a regular fanzine review column, providing contact information so that readers could obtain the fanzines directly.[15] Initially the stories for the "Hall of Fame" were chosen by the editor, but soon Weisinger recruited well-known science fiction fans to make the choices.[15]

Startling was popular, and soon "became one of the core science fiction magazines", according to science fiction historian Mike Ashley. The target audience was younger readers, and the lead novels were often space operas by well-known pulp writers such as Edmond Hamilton and Manly Wade Wellman. In addition to space opera, some more fantastical fiction began to appear, contributed by writers such as Henry Kuttner. These early science fantasy stories were popular with the readers, and contrasted with the hard science fiction that John W. Campbell was pioneering at Astounding.[4]

Weisinger set out to please the younger readers, and when Friend became editor in 1941, he went further in this direction, giving the magazine a strongly juvenile flavor. For example, Friend introduced "Sergeant Saturn", a character (originally from Thrilling Wonder Stories) who answered readers' letters and appeared in other features in the magazine. Many subscribers found the approach irritating.[7][15][23]

The interior artwork was initially done by Hans Wessolowski (more usually known as "Wesso"), Mark Marchioni and Alex Schomburg, and occasionally Virgil Finlay.[15] The initial cover art was mostly painted by Howard Brown,[15] but when Earle K. Bergey began to paint covers for Startling in 1940, soon after its launch, Bergey quickly became identified with the magazine; between 1940 and 1952 (the year of Bergey's death) he painted the great majority of covers. Bergey's covers were visually striking: in the words of science fiction editor and critic Malcolm Edwards, they typically featured "a rugged hero, a desperate heroine (in either a metallic bikini or a dangerous state of déshabillé) and a hideous alien menace".[7][12] The brass bra motif came to be associated with Bergey, and his covers did much to create the image of science fiction as it was perceived by the general public.[24]

Merwin and after

When Merwin became editor in 1945 he brought changes, but artist Earle K. Bergey retained the creative freedom he had come to expect given his relationship with Standard. Some argue that Bergey's covers became more realistic,[7][23] and Merwin managed to improve the interiors of Startling to the point of being a serious rival to Astounding, acknowledged leader of the field. Critics' opinions vary on the relative quality of the magazines of this era; Malcolm Edwards regards Startling as second only to Astounding, but Ashley considers Thrilling Wonder to be Astounding's closest challenger in the late 1940s.[7][25] Merwin's discoveries included Jack Vance, whose first story, "The World Thinker", appeared in the Summer 1945 issue.[23] He also regularly published work by Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore, who wrote both under Kuttner's name and as "Keith Hammond": in a four-year period from 1946 to 1949 the writing team of Kuttner and Moore had seven novels published in Startling, mostly science fantasy, a subgenre not common at that time.[15] Notable novels that appeared in the late 1940s include Fredric Brown's What Mad Universe and Charles L. Harness's Flight Into Yesterday, later published in book form as The Paradox Men. Arthur C. Clarke's novel The City and the Stars first saw print in Startling in abbreviated form, in the November 1948 issue, under the title Against the Fall of Night.[7]

One novel that did not appear in Startling was Isaac Asimov's Pebble in the Sky, which Merwin had commissioned from Asimov in the early summer of 1947. After the unusual step of allowing the editor to twice read the work-in-progress and receiving nothing but approval, Asimov delivered a completed draft in September. This time, Merwin asked for revisions: Leo Margulies, Merwin's boss, had decided that Startling needed to focus more on action and adventure in the style of Amazing, and less on cerebral stories in the style of Astounding. Asimov, "for the first and only time of [his] life...openly lost [his] temper with an editor", stalked out of the room with his manuscript and never submitted anything to Merwin again, though he later expressed a softening of feeling and admitted Merwin had been within his rights.[26]

Another title in the Standard Magazines stable was Captain Future, which had been launched a year after Startling, and featured the adventures of the superhero after whom the magazine was named. When it folded with its Spring 1944 issue, the series of novels was continued for some time in the pages of Startling; over the next six years ten more "Captain Future" novels appeared, with the last one, Birthplace of Creation, printed in the May 1951 issue.[15][27][28]

Merwin's successor, Mines, also published some excellent work, though increased competition in the early 1950s from Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction did lead to some dilution of quality,[7] and Startling's rates—one to two cents per word—could not compete with the leading magazines.[29] However, Startling's editorial policy was more eclectic: it did not limit itself to one kind of story, but printed everything from melodramatic space opera to sociological sf,[15] and Mines had a reputation as having "the most catholic tastes and the fewest inhibitions" of any of the science fiction magazine editors.[29] In late 1952, Mines published Philip José Farmer's "The Lovers", a taboo-breaking story about aliens who can only reproduce by mating with humans. Illustrated with an eye-popping cover by Bergey, Farmer's ground-breaking story integrated sex into the plot without being prurient, and was widely praised. Farmer, partly as a consequence, went on to win a Hugo Award as "Most Promising New Writer". New authors first published by Mines include Frank Herbert, who debuted with "Looking for Something?" in April 1952, and Robert F. Young, whose first story, "The Black Deep Thou Wingest", appeared in June 1953.[7][15][16][23] The artwork was also high quality; Virgil Finlay's interior illustrations were "unparalleled", according to science fiction historian Robert Ewald. Other well-known artists who contributed interior work included Alex Schomburg and Kelly Freas.[15]

Startling's instantly recognizable title logo was redolent of the magazine's pulp roots, and in early 1952 Mines decided to replace it with a more staid typeface.[7] The covers became more sober, with spaceships replacing the women in brass bras.[15] With the Spring 1955 issue, at the start of its final year, Startling dropped its long-standing policy of printing a novel in every issue, but only three issues later it ceased publication.[15]

Bibliographic details

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1939 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | ||||||

| 1940 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 4/1 | 4/2 | 4/3 | ||||||

| 1941 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | ||||||

| 1942 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | ||||||

| 1943 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 10/1 | ||||||||

| 1944 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 11/1 | 11/2 | ||||||||

| 1945 | 11/3 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | ||||||||

| 1946 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 14/1 | 14/2 | |||||||

| 1947 | 14/3 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 16/1 | 16/2 | ||||||

| 1948 | 16/3 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 18/1 | 18/2 | ||||||

| 1949 | 18/3 | 19/1 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 20/1 | 20/2 | ||||||

| 1950 | 20/3 | 21/1 | 21/2 | 21/3 | 22/1 | 22/2 | ||||||

| 1951 | 22/3 | 23/1 | 23/2 | 23/3 | 24/1 | 24/2 | ||||||

| 1952 | 24/3 | 25/1 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | 28/1 | 28/2 |

| 1953 | 28/3 | 29/1 | 29/2 | 29/3 | 30/1 | 30/2 | 30/3 | 31/1 | ||||

| 1954 | 31/2 | 31/3 | 32/1 | 32/2 | ||||||||

| 1955 | 32/3 | 33/1 | 33/2 | 33/3 | ||||||||

| Issues of Startling Stories, showing volume/issue number, and color-coded to show who was editor for each issue. The editors, in sequence, were Mort Weisinger, Oscar J. Friend, Sam Merwin, Jr., Samuel Mines, Theron Raines, and Herbert D. Kastle, though different references disagree on who was editor during 1955.[14] Underlining indicates that an issue was titled as a quarterly (e.g. "Fall 1949") rather than as a monthly. | ||||||||||||

The editorial succession at Startling was as follows:[13][14][note 2]

- Mort Weisinger: January 1939 – May 1941.

- Oscar J. Friend: July 1941 – Fall 1944.

- Sam Merwin, Jr.: Winter 1945 – September 1951.

- Samuel Mines: November 1951 – Fall 1954.

- Theron Raines: Winter 1955 – Spring 1955.

- Herbert D. Kastle: Summer 1955 – Fall 1955.

Startling was a pulp-sized magazine for all of its 99 issues. It initially was 132 pages, and was priced at 15 cents. The page count was reduced to 116 pages with the Summer 1944 issue and then increased to 148 pages with the March 1948 issue, at which time the price went up to 20 cents. The price increased again, to 25 cents, in November 1948, and the page count increased again to 180 pages. This higher page count did not last; it was reduced to 164 in March 1949 and then again to 148 pages in July 1951. The October 1953 issue saw the page count drop again, to 132, and a year later the Fall 1954 issue cut the page count to 116. The magazine remained at 116 pages and a price of 25 cents for the rest of its existence.[12]

The original bimonthly schedule continued until the March 1943 issue, which was followed by June 1943 and then Fall 1943. This inaugurated a quarterly schedule that ran until Fall 1946, except that an additional issue, dated March, was inserted between the Winter 1946 and Spring 1946 issues. The next issue, January 1947, began another bimonthly sequence, which ran without interruption until November 1951. With the following issue, January 1952, Startling switched to a monthly schedule, which lasted until the June 1953 issue which was followed by August and October 1953 and then January 1954. The next issue was Spring 1954, and the magazine stayed on a quarterly schedule from then until the last issue, Fall 1955.[12]

There was a British reprint edition from Pembertons between 1949 and 1954. These were heavily cut, with sometimes only one or two stories and usually only 64 pages, though the October and December 1952 issues both had 80 pages. It was published irregularly; initially once or twice a year, and then more or less bimonthly beginning in mid-1952. The issues were numbered from 1 to 18. Three different Canadian reprint editions also appeared for a total of 21 or 22 issues (sources differ on the correct number).[note 3] Six quarterly issues appeared from Summer 1945 through Fall 1946 from Publication Enterprises, Ltd.; then another three bimonthly issues appeared, from May to September 1948, from Pines Publications. Finally 12 more bimonthly issues appeared from March 1949 to January 1951, from Better Publications of Canada. All these issues were almost identical to the American versions, although they are half an inch taller.[7][12][20] A Mexican magazine, Enigmas, ran for 16 issues from August 1955 to May 1958; it included many reprints, primarily from Startling and from Fantastic Story Magazine.[30]

Derivative anthologies

Two anthologies of stories from Startling have been published. In 1949 Merlin Press brought out From Off This World, edited by Leo Margulies and Oscar Friend, which included stories that had appeared in the "Hall of Fame" reprint section of the magazine. Then in 1954 Samuel Mines edited The Best from Startling Stories, published by Henry Holt;[7] despite the title, the stories were reprinted from both Startling and its sister magazine, Thrilling Wonder Stories.[20] The anthology was reprinted twice in the UK under different titles; as Startling Stories in 1954, published by Cassell, and then in 1956 as a Science Fiction Book Club edition titled Moment in Time.[31] P. Schuyler Miller praised it as "an excellent collection by anyone's standards."[32]

Notes

- ↑ According to science fiction historian Robert Ewald, this is the only time the junior science fiction magazine at a publisher has become the more successful publication.[15]

- 1 2 Unusually, science fiction magazine references give multiple versions of the editorship for the last year. The Tymn & Ashley Encyclopedia says that Alexander Samalman and Herbert D. Kastle edited the last four issues together, while Donald Tuck, in his Encyclopedia, gives Samalman as the editor of the last four issues. Both Malcolm Edwards and Mike Ashley (in the latest (online) edition of the Nicholls & Clute Encyclopedia) and Ashley's Transformations agree, however, and as these are the latest sources their version is given here.[15][19][20]

- ↑ Tuck says that there were 22 but then enumerates them and only lists 21. Malcolm Edwards gives the figure as 22 but does not list them.[7][20]

References

- ↑ http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/startling_stories

- ↑ Edwards & Nicholls (1993), pp. 1066–1068.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 Ashley (2000), pp. 136–139.

- ↑ Williamson (1984), p. 116.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Edwards (1993b), p. 1156.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 254.

- ↑ Edwards (1993c), p. 1311.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 123.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), pp. 187–188.

- 1 2 3 4 5 See the individual issues. For convenience, an online index is available at "Magazine:Startling Stories — ISFDB". Al von Ruff (Publisher). Retrieved 4 July 2008. An index to the Canadian and British reprints is at "Visco navigation". Terry Gibbons. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- 1 2 3 Ashley (2000), p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ashley, Transformations, p. 343.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Ewald (1985), pp. 611–617.

- 1 2 Ashley (2005), p. 12–16.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), pp. 220–225.

- ↑ Ashley (2005), pp. 69–73.

- ↑ Edwards, Malcolm & Ashley, Mike. "Culture: Startling Stories: SFE: Science Fiction Encyclopedia". Science Fiction Encyclopedia. Gollancz. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Startling Stories", in Tuck, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Vol. 3, pp. 594–595.

- ↑ di Fate (1997), p. 35.

- ↑ del Rey (1979), p. 120.

- 1 2 3 4 Ashley (2000), pp. 187–190.

- ↑ Ashley (1976), opposite p. 153.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), pp. 188–190.

- ↑ Asimov (1979), pp. 498–499, 507–508.

- ↑ Ashley (2000), p. 253.

- ↑ For convenience, an online index of the Captain Future series is available at "Captain Future - Series Bibliography". Al von Ruff (Publisher). Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- 1 2 de Camp (1953), pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Pessina (1985), p. 887.

- ↑ "Mines, Samuel", in Tuck, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Vol. 2, p. 314.

- ↑ "The Reference Library", Astounding Science Fiction, July 1954, pp.148–49

Sources

- Ashley, Michael (1976) [First edition 1975]. The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 2 1936–1945. Chicago: Henry Regnery. ISBN 0-8092-8002-7.

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-779-4.

- Asimov, Isaac (1979). In Memory Yet Green. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-13679-X.

- de Camp, L. Sprague (1953). Science-Fiction Handbook: The Writing of Imaginative Fiction. New York: Hermitage House.

- del Rey, Lester (1979). The World of Science Fiction: 1926–1976: The History of a Subculture. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25452-X.

- di Fate, Vincent (1997). Infinite Worlds. New York: The Wonderland Press. ISBN 0-670-87252-0.

- Edwards, Malcolm; Nicholls, Peter (1993a). "SF Magazines". In Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 1066–1068. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- Edwards, Malcolm (1993b). "Startling Stories". In Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 1156. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- Edwards, Malcolm (1993c). "Weisinger, Mortimer". In Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 1311. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- Ewald, Robert (1985). "Startling Stories". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike. Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 611–617. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Mines, Samuel (1954). Startling Stories. London: Cassell.

- Mines, Samuel (1956). Moment in Time. London: Science Fiction Book Club.

- Pessina, Hector (1985). "Mexico". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike. Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 887. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1978). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 2. Chicago: Advent: Publishers. ISBN 0-911682-22-8.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent: Publishers. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.

- Williamson, Jack (1984). Wonder's Child. New York: Blue Jay.

External links