Stickler syndrome

| Stickler syndrome (hereditary progressive arthro-ophthalmopathy) | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q87.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 759.89 |

| OMIM | 108300 277610 184840 |

| DiseasesDB | 29327 |

Stickler syndrome (hereditary progressive arthro-ophthalmopathy) is a group of genetic disorders affecting connective tissue, specifically collagen.[1] Stickler syndrome is a subtype of collagenopathy, types II and XI. Stickler syndrome is characterized by distinctive facial abnormalities, ocular problems, hearing loss, and joint problems. It was first studied and characterized by Gunnar B. Stickler in 1965.[1]

Types

Genetic changes are related to the following types of Stickler syndrome:[2][3]

- Stickler syndrome, COL2A1 (75% of Stickler cases)

- Stickler syndrome, COL11A1

- Stickler syndrome, COL11A2 (non-ocular)

- Stickler syndrome, COL9A1 (recessive variant)

Whether there are two or three types of Stickler syndrome is controversial. Each type is presented here according to the gene involved. The classification of these conditions is changing as researchers learn more about the genetic causes.

Signs and symptoms

Individuals with Stickler syndrome experience a range of signs and symptoms. Some people have no signs and symptoms; others have some or all of the features described below. In addition, each feature of this syndrome may vary from subtle to severe.[4]

A characteristic feature of Stickler syndrome is a somewhat flattened facial appearance. This is caused by underdeveloped bones in the middle of the face, including the cheekbones and the bridge of the nose. A particular group of physical features, called the Pierre Robin sequence, is common in children with Stickler syndrome. Robin sequence includes a U-shaped or sometimes V-shaped cleft palate (an opening in the roof of the mouth) with a tongue that is too large for the space formed by the small lower jaw. Children with a cleft palate are also prone to ear infections and occasionally swallowing difficulties.

Many people with Stickler syndrome are very nearsighted (described as having high myopia) because of the shape of the eye. People with eye involvement are prone to increased pressure within the eye (ocular hypertension) which could lead to glaucoma and tearing or detachment of the light-sensitive retina of the eye (retinal detachment). Cataract may also present as an ocular complication associated with Stickler's Syndrome. The jelly-like substance within the eye (the vitreous humour) has a distinctive appearance in the types of Stickler syndrome associated with the COL2A1 and COL11A1 genes. As a result, regular appointments to a specialist ophthalmologist are advised. The type of Stickler syndrome associated with the COL11A2 gene does not affect the eye.[2]

People with this syndrome have problems that affect things other than the eyes and ears.[4] Arthritis, abnormality to ends of long bones, vertebrae abnormality, curvature of the spine, scoliosis, joint pain, and double jointedness are all problems that can occur in the bones and joints. Physical characteristics of people with Stickler can include flat cheeks, flat nasal bridge, small upper jaw, pronounced upper lip groove, small lower jaw, and palate abnormalities, these tend to lessen with age and normal growth and palate abnormalities can be treated with routine surgery.

Another sign of Stickler syndrome is mild to severe hearing loss that, for some people, may be progressive (see hearing loss with craniofacial syndromes). The joints of affected children and young adults may be very flexible (hypermobile). Arthritis often appears at an early age and worsens as a person gets older. Learning difficulties, not intelligence, can also occur because of hearing and sight impairments if the school is not informed and the student is not assisted within the learning environment.[5][6]

Stickler syndrome is thought to be associated with an increased incidence of mitral valve prolapse of the heart, although no definitive research supports this.

Causes

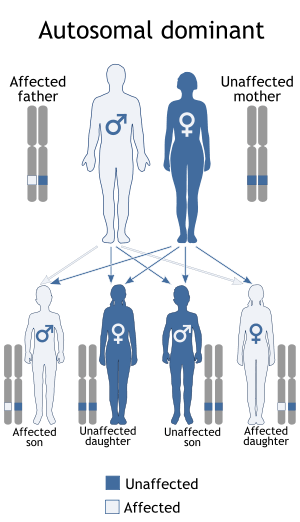

The syndrome is thought to arise from a mutation of several collagen genes during fetal development. It is a sex independent autosomal dominant trait meaning a person with the syndrome has a 50% chance of passing it on to each child. There are three variants of Stickler syndrome identified, each associated with a collagen biosynthesis gene. A metabolic defect concerning the hyaluronic acid and the collagen of the 2-d type is assumed to be the cause of this syndrome.

Genetics

Mutations in the COL11A1, COL11A2 and COL2A1 genes cause Stickler syndrome. These genes are involved in the production of type II and type XI collagen. Collagens are complex molecules that provide structure and strength to connective tissue (the tissue that supports the body's joints and organs). Mutations in any of these genes disrupt the production, processing, or assembly of type II or type XI collagen. Defective collagen molecules or reduced amounts of collagen affect the development of bones and other connective tissues, leading to the characteristic features of Stickler syndrome.[2][3][4][6][7]

Other, as yet unknown, genes may also cause Stickler syndrome because not all individuals with the condition have mutations in one of the three identified genes.[8]

Treatment

Many professionals that are likely to be involved in the treatment of those with Stickler's syndrome, include oral and maxillofacial surgeons; craniofacial surgeons; ear, nose, and throat specialists, ophthalmologists, optometrists, audiologists and rheumatologists.

Epidemiology

Overall, the estimated prevalence of Stickler syndrome is about 1 in 10,000 people. Stickler syndrome affects 1 in 7,500 to 9,000 newborns.

History

Scientists associated with the discovery of this syndrome include:

- B. David (medicine)

- Gunnar B. Stickler

- G. Weissenbacher

- Ernst Zweymüller

See also

- Mandy Haberman, invented the Haberman Feeder when her daughter, born with Stickler syndrome, required special feeding due to cleft palate.

- Marshall syndrome

- Pierre Robin syndrome

References

- 1 2 Stickler G. B.; Belau P. G.; Farrell F. J.; Jones J. F.; Pugh D. G.; Steinberg A. G.; Ward L. E. (1965). "Hereditary Progressive Arthro-Ophthalmopathy". Mayo Clin Proc. 40: 433–55. PMID 14299791.

- 1 2 3 Annunen S, Korkko J, Czarny M, Warman ML, Brunner HG, Kaariainen H, Mulliken JB, Tranebjaerg L, Brooks DG, Cox GF, Cruysberg JR, Curtis MA, Davenport SL, Friedrich CA, Kaitila I, Krawczynski MR, Latos-Bielenska A, Mukai S, Olsen BR, Shinno N, Somer M, Vikkula M, Zlotogora J, Prockop DJ, Ala-Kokko L (1999). "Splicing mutations of 54-bp exons in the COL11A1 gene cause Marshall syndrome, but other mutations cause overlapping Marshall/Stickler phenotypes". Am J Hum Genet. 65 (4): 974–83. doi:10.1086/302585. PMC 1288268

. PMID 10486316.

. PMID 10486316. - 1 2 Liberfarb RM, Levy HP, Rose PS, Wilkin DJ, Davis J, Balog JZ, Griffith AJ, Szymko-Bennett YM, Johnston JJ, Francomano CA, Tsilou E, Rubin BI (2003). "The Stickler syndrome: genotype/phenotype correlation in 10 families with Stickler syndrome resulting from seven mutations in the type II collagen gene locus COL2A1". Genet Med. 5 (1): 21–7. doi:10.1097/00125817-200301000-00004. PMID 12544472.

- 1 2 3 Richards AJ, Baguley DM, Yates JR, Lane C, Nicol M, Harper PS, Scott JD, Snead MP (2000). "Variation in the vitreous phenotype of Stickler syndrome can be caused by different amino acid substitutions in the X position of the type II collagen Gly-X-Y triple helix". Am J Hum Genet. 67 (5): 1083–94. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)62938-3. PMC 1288550

. PMID 11007540.

. PMID 11007540. - ↑ Admiraal RJ, Szymko YM, Griffith AJ, Brunner HG, Huygen PL (2002). "Hearing impairment in Stickler syndrome". Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 61: 216–23. PMID 12408087.

- 1 2 Nowak CB (1998). "Genetics and hearing loss: a review of Stickler syndrome". J Commun Disord. 31 (5): 437–53; 453–4. doi:10.1016/S0021-9924(98)00015-X. PMID 9777489.

- ↑ Snead MP, Yates JR (1999). "Clinical and Molecular genetics of Stickler syndrome". J Med Genet. 36 (5): 353–9. doi:10.1136/jmg.36.5.353. PMC 1734362

. PMID 10353778.

. PMID 10353778. - ↑ Parke DW (2002). "Stickler syndrome: clinical care and molecular genetics". Am J Ophthalmol. 134 (5): 746–8. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01822-6. PMID 12429253.

External links

- Stickler Involved People, the U.S. support group for those with Stickler Syndrome

- Information about Stickler Syndrome from Seattle Children's Craniofacial Center

- UK Stickler Syndrome Support Group

- Vision Support Guide

- US Stickler Syndrome Support Group

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Stickler Syndrome

- Who named it?

- Information sur le Syndrome de Stickler French written website on Stickler Syndrome.

- Cambridge University NHS Foundation Trust UK Vitreoretinal Service (Research and treatment for Stickler syndrome)