Strez

| Strez | |

|---|---|

| sebastokrator | |

| Noble family | Asen dynasty |

| Born | 12th century |

| Died |

1214 Polog Valley |

Strez (Bulgarian: Стрез; original spelling: СТРѢЗЪ[1]) (fl. 1207–1214) was a Bulgarian sebastokrator and a member of the Asen dynasty. A major contender for the Bulgarian throne, Strez initially opposed the ascension of his close relative Tsar Boril. He fled to Serbia, where he accepted the vassalage of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanjić, and Serbian support helped him establish himself as a largely independent ruler in a large part of the region of Macedonia. However, Strez turned against his suzerains to become a Bulgarian vassal and joined forces with his former enemy Boril against the Latins and then the Serbs. Strez was murdered amidst a major anti-Serbian campaign under unclear circumstances in a plot that likely involved Saint Sava.

Throne contender and Serbian vassal

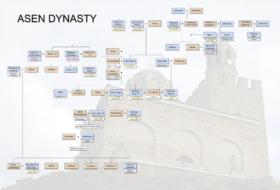

Nothing is mentioned of Strez until the events in the wake of the sudden death of Tsar Kaloyan (1197–1207) during his siege of the Crusader-held Thessaloniki.[2] Just like Alexius Slav, another noble who would later emerge as a separatist, Strez was a nephew of the Asen brothers Peter, Ivan Asen and Kaloyan, who were the first three emperors of the Second Bulgarian Empire.[3] However, it is unclear whether through his relation to the early Asens he was a first cousin or a brother of Boril (1207–1218).[4][5][6]

At the time of Kaloyan's death, Strez was in the capital Tarnovo, perhaps seeking to capitalize on his ancestral rights to the Bulgarian crown. However, Boril proved to be the more ambitious candidate. Boril persecuted the other candidates for the throne, and Alexius Slav, along with Ivan Asen's sons Ivan Asen II had to leave Bulgaria.[7]

As happened to other members of the royal family, Boril's ascension forced Strez and his closest supporters to flee, in that case to neighbouring Serbia, where he was welcomed by the reigning Stefan Nemanjić (1196–1228) in 1207 or early 1208.[3][8] Even though Boril requested the extradition of Strez to Bulgaria,[9] the Serbian ruler hoped to use Strez as a puppet in gaining Bulgarian-held territory. Stefan believed that Strez's royal ancestry and imperial aspirations would make it much easier to impose Serbian rule over Macedonia, Kosovo and Braničevo, as well as Belgrade, all captured by Bulgaria under Kaloyan.[10] At the same time, Boril was unable to take military action against Strez and his Serbian patron, as he had suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Latins at Plovdiv.[8][11][12] Stefan went as far as to become a blood brother of Strez in a ceremony which Stefan was hoping would secure Strez's loyalty.[2][7]

In 1208, Strez headed a Serbian force which seized much of the Vardar valley from Bulgaria. He established himself as a Serbian vassal at the Prosek fortress (near modern Demir Kapija), formerly the capital of another Bulgarian separatist, Dobromir Chrysos. By 1209, Strez's realm spread over much of Macedonia,[3][5][8] from the Struma valley in the east, where he bordered the lands controlled by Boril, to Bitola and perhaps Ohrid in the west, and from Skopje in the north to Veria in the south. While Strez quickly gained the support of the local Bulgarian population and possibly inherited the remaining administration from Boril's rule, Serbian units nevertheless remained in his domains, either to guarantee his loyalty or with the intent to oust him and annex his lands.[13]

Bulgarian vassal

Alexius Slav's marriage to the daughter of Latin Emperor Henry of Flanders in 1209 was potentially a great danger to Boril, who could be facing their joint forces. Fearing such a coalition, Boril approached Strez, who was at the time gaining more power and was close to complete independence from Serbia.[12] Strez agreed to a union with his former enemy, though only after Boril reconfirmed his complete autonomy.[14][15] Strez eliminated the remaining Serbian troops in his lands in an act that the Serbs saw as devil-inspired treason. It is not impossible that Boril persuaded Strez through military action, though it is more likely that the union was achieved through negotiations.[16]

In the same year, Strez and Boril had come to peace with Michael I Komnenos Doukas, the ruler of Epirus. In late 1209, Strez and Michael may have attempted a joint campaign against Thessaloniki,[17] as they both lost lands to the Latins in what was likely a retaliation raid in late 1209 or early 1210. The failure of this attack prompted Michael to break away from his Bulgarian allies and support the Latins. In early 1211, Strez clashed with the Latins and Epirotes at Thessaloniki and required Boril's assistance after Michael and Henry invaded the western reaches of Strez's realm. In the early summer, the allied Bulgarian army suffered a heavy defeat at Bitola[3][15] at the hands of Michael, Henry's brother Eustace and Bernard of Katzenellenbogen.[18] Even though it resulted in no territorial losses,[17] it prevented Strez from an expansion to the south. In relation to an anti-Bogomil council in 1211, Strez is referred to as a sebastokrator. The title was either conferred to him by Boril as part of their agreement in 1209, or was awarded to Strez by Kaloyan during his rule. In any case, Boril certainly recognized Strez's right to that appellation. There are signs that Strez divided his possessions into administrative units, each headed by a sebastos.[19] In 1212, Strez was powerful enough to be considered one of the Latin Empire's chief adversaries, along with Boril, Michael and Nicaean emperor Theodore I Laskaris, by Henry himself.[15][17]

Anti-Serbian campaign and death

After a series of military failures against the Latins, Boril made peace with Henry in 1213, cemented through two royal marriages.[20][21] As Boril's vassal, Strez joined the Bulgarian–Latin union, the short-term goal of which was a double invasion of Serbia.[22][23] In 1214, the forces of Boril and Henry attacked Serbia from the east, while Strez's army, deemed in contemporary sources to be "countless",[17] penetrated Serbian territory from the south and reached the Polog. Facing a major invasion on two fronts, the Serbs were quick to ask for peace. After Stefan's envoys to Strez failed, he sent his brother, archbishop Sava (canonized as Saint Sava) to Strez's camp.[24][25]

Even though Sava's diplomacy was of no effect either,[3] Strez died the night after Sava's departure. Serbian sources present the death of Strez as a miracle, Strez being stabbed by an angel,[26] though in reality he was very likely murdered in a plot orchestrated by Sava.[24] Historian John V. A. Fine theorizes that Sava may have found supporters among Strez's nobles, some of whom had turned against him and organized his murder, only to defect to Serbia immediately afterwards. According to the hagiography of Saint Sava, in his dying words Strez claimed he was stabbed by a young soldier on the order of Sava.[27][28]

While Strez's murder meant an end to the Latin–Bulgarian campaign, Stefan did not undertake a campaign into Macedonia due to the proximity of the coalition troops, which had halted at Niš. In 1217, all of Strez's territory was under the Epirote rule of Theodore Komnenos Doukas,[3][22][24] though Boril may have controlled some or all of it in the meantime.[29] The Serbs failed to take advantage of Strez's death as far as they did not manage to acquire any of his former domains.[26]

Assessment and legacy

Contemporary Serbian sources, such as the hagiography of Saint Sava, are highly critical of Strez's actions. The Serbs accused Strez of recklessness, drunkenness, ungodliness, treason and cruelty. The hagiography of Saint Sava tells of Strez's alleged tendency to have captives thrown from a high cliff into the Vardar River for his and his guests' entertainment. As the prisoners were falling to their death, Strez would sarcastically shout at them not to get their coats wet.[30][31] Bulgarian historian Ivan Lazarov dismisses these allegations as slanderous. In his biography of Strez, he hails the medieval ruler as a "true member of the Asen dynasty" and defends his actions due to him being a "child of his time". Lazarov assesses Strez as a characteristic, vivid personality who put his independence above all.[26]

The name of Strez has become a part of Bulgarian folklore,[26] including a legendary account of his life written down as the Biography of Prince Stregan in the 18th century or later.[15][32] At least one location throughout Macedonia was tied by the locals with Strez, whom the folk interpreted as a voivode or hajduk who defended the people against the Ottomans. Some ruins by the Vardar River near Jegunovce west of Skopje were known to the locals as "Strez's Fortress" (Стрезово кале, Strezovo kale).[33] Even though in reality his capital, Prosek, lay far to the south, the castle at Jegunovce may have formed part of Strez's border fortifications, or it may have been the site of his negotiations with Sava and his murder.[34]

References and notes

- ↑ Rendered as Στρέαζος, Streazos in Byzantine Greek and as Straces or Stratius in Latin sources. Златарски, p. 270

- 1 2 Божилов, p. 98

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Бакалов (2003)

- ↑ Fine, p. 94

- 1 2 Павлов

- ↑ Андреев (1999), p. 353

- 1 2 Андреев (1999), p. 354

- 1 2 3 Curta, p. 385

- ↑ Андреев (2004), p. 179

- ↑ Fine, pp. 94–95

- ↑ Velimirović, p. 61

- 1 2 Андреев (2004), p. 180

- ↑ Fine, pp. 95–96

- ↑ Андреев (2004), p. 181

- 1 2 3 4 Божилов, p. 99

- ↑ Fine, pp. 97–98

- 1 2 3 4 Андреев (1999), p. 355

- ↑ Housley, p. 73

- ↑ Fine, p. 98

- ↑ Fine, pp. 100–101

- ↑ Андреев (2004), p. 182

- 1 2 Бакалов (2007), p. 154

- ↑ Fine, p. 101

- 1 2 3 Андреев (2004), p. 183

- ↑ Fine, p. 103

- 1 2 3 4 Андреев (1999), p. 356

- ↑ Fine, pp. 103–104

- ↑ Velimirović, p. 62

- ↑ Fine, p. 104

- ↑ Velimirović, pp. 60–62

- ↑ Андреев (1999), pp. 355–356

- ↑ Мутафчиев, p. 110

- ↑ Мутафчиев, p. 276

- ↑ Мутафчиев, p. 280

Sources

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. pp. 175–184. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- Housley, Norman (2007). Knighthoods of Christ: essays on the history of the Crusades and the Knights Templar, presented to Malcolm Barber. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5527-5.

- Velimirović, Nikolaj (1989). The life of St. Sava. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-065-5.

- Андреев, Йордан; Лазаров, Иван; Павлов, Пламен (1999). Кой кой е в средновековна България [Who is Who in Medieval Bulgaria] (in Bulgarian). Петър Берон. ISBN 978-954-402-047-7.

- Андреев, Йордан; Пантев, Андрей (2004). Българските ханове и царе [Bulgarian Khans and Tsars] (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново: Абагар. ISBN 978-954-427-216-6.

- Бакалов, Георги; Куманов, Милен (2003). "СТРЕЗ (неизв.-ок. 1214)" [STREZ (unknown — c. 1214)]. Електронно издание "История на България" [Electronic edition "History of Bulgaria"] (CD) (in Bulgarian). София: Труд, Сирма. ISBN 954528613X.

- Бакалов, Георги (2007). История на българите: Военна история на българите от древността до наши дни [History of the Bulgarians: Military History of the Bulgarians from Antiquity to Modern Times] (in Bulgarian). София: Труд. ISBN 978-954-621-235-1.

- Божилов, Иван (1994). Фамилията на Асеневци (1186–1460). Генеалогия и просопография [The Family of the Asens (1186–1460). Genealogy and prosopography] (in Bulgarian). София: Издателство на Българската академия на науките. ISBN 954-430-264-6.

- Златарски, Васил (1972) [1940]. Димитър Ангелов, ed. История на българската държава през средните векове. Второ българско царство. България при Асеневци (1187–1280) [History of the Bulgarian State in the Middle Ages. Second Bulgarian Empire. Bulgaria Under the Asens (1187–1280)] (in Bulgarian). Том III (2nd ed.). София: Наука и изкуство. OCLC 611774943.

- Мутафчиев, Петър (1993) [1911]. "Владетелите на Просек. Страници из историята на българите в края на XII и началото на XIII век" [The rulers of Prosek. Pages from the history of the Bulgarians in the late 12th and early 13th century]. Изток и Запад в европейското Средновековие. Избрано [East and West in the European Middle Ages. Selected Works] (in Bulgarian). София: Христо Ботев. ISBN 978-954-445-079-3.

- Павлов, Пламен (2005). "Съперничества и кървави борби за престола на Асеневци" [Rivalries and bloody struggles for the throne of the Asens]. Бунтари и авантюристи в средновековна България [Rebels and Venturers in Medieval Bulgaria] (in Bulgarian). Варна: LiterNet. ISBN 954-304-152-0. Retrieved 11 November 2010.