Sunset Boulevard

Sunset Blvd near Vine Street | |

| |

| West end |

|

|---|---|

| Major junctions |

|

| East end | Figueroa Street in Downtown Los Angeles |

Sunset Boulevard is a boulevard in the central and western part of Los Angeles County, California that stretches from Figueroa Street in Downtown Los Angeles to the Pacific Coast Highway at the Pacific Ocean.

Geography

Approximately 22 miles (35 km) in length,[1] the boulevard roughly traces the arc of mountains that form part of the northern boundary of the Los Angeles Basin, following the path of a 1780s cattle trail from the Pueblo de Los Angeles to the ocean.[2]

From Downtown Los Angeles, it heads northwest, to Hollywood, through which it travels due west for several miles before it bends southwest towards the ocean. It passes through or near Echo Park, Silver Lake, Los Feliz, Hollywood, West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, and Holmby Hills. In Bel-Air, Sunset Boulevard runs along the northern boundary of UCLA's Westwood campus. The boulevard continues through Brentwood to Pacific Palisades where it terminates at the Pacific Coast Highway intersection.

The boulevard has curvaceous winding stretches, and can be treacherous for unaware drivers in some sections. It is at least four lanes wide along its entire route. Sunset is frequently congested with traffic loads beyond its design capacity.

Sunset Boulevard historically extended farther east than it now does, starting at Alameda Street near Union Station and beside Olvera Street in the historic section of Downtown. The portion of Sunset Boulevard east of Figueroa Street was renamed Cesar Chavez Avenue[1] in 1994 along with Macy Street and Brooklyn Avenue in honor of the late Mexican-American union leader and civil rights activist.

History

In 1877, one of the earlier real estate owners from "back East" Horace H. Wilcox, decided to subdivide his more than 20 acres of land (mostly orchards and vineyards) along Sunset Boulevard, including what is today Hollywood and Vine.[3]

In 1890, Belgian diplomat Victor Ponet bought 240 acres of the former Rancho La Brea land grant.[4] His son-in-law, Francis S. Montgomery, inherited this property and created Sunset Plaza.[5]

According to a 1901 article in the Los Angeles Herald, Sunset only extended from Hollywood in the west to Marion Avenue in the Echo Park district in the east.[6] A proposal was introduced by the Board of Public Works to extend Sunset east to Main Street in the Plaza by routing the road over the existing section of Bellevue Avenue,[7] but the plan was delayed for a number of years due to active opposition by affected land owners[8] until approximately 1904.[9][10] According to the 1910[11] Baist Real Estate Survey Atlas, Sunset Boulevard reached the Plaza by that time, but it did so by two short and narrow segments which were not aligned with each other and thus did not provide a proper thoroughfare to it. In late 1912 several properties along the route were condemned so that the boulevard could be changed in both its width and its alignment.[12][13] With these changes completed, Sunset Boulevard now reached North Main Street and continued as Marchessault along the northern end of the Plaza. This section, variously marked and signed as Marchessault Street or East Sunset Boulevard, remained open to traffic until the late 1960s or early 1970s.[14] At that time Sunset was realigned one block north and Marchessault was closed to motor traffic.

In 1921, a westward expansion of Sunset began, extending the road from the then-current terminus at Sullivan Canyon through Santa Monica to the coast. This land, a portion of the original 1838 holdings of Fransisco Marquez, stretched across a mesa and became known as the "Riviera section." Will Rogers, who had bought much of this land as an investment, later donated it to the State of California creating Will Rogers State Historic Park.[15] Circa 1931, Sunset was a paved road from Horn Avenue to Havenhurst Avenue.[16]

Cultural aspects

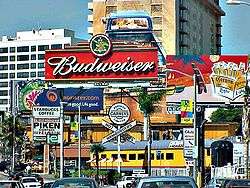

The Sunset Strip portion of Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood has been famous for its active nightlife at least since the 1950s.[17]

In the 1970s, the area between Gardner Street and Western Avenue was a center for street prostitution.[18] Shortly after a well publicized June 1995 incident, police raids drove out the majority of prostitutes on the Boulevard.

Part of Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood is also sometimes called "Guitar Row" due to the large number of guitar stores and music industry-related businesses,[19] including the recording studios Sunset Sound Studios and United Western Recorders.

The portion of Sunset Boulevard that passes through Beverly Hills was once named Beverly Boulevard.

The boulevard is commemorated in Billy Wilder's 1950 film Sunset Boulevard, the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical of the same name, and the 1950s television series 77 Sunset Strip. Jan and Dean's 1960s hit song "Dead Man's Curve" refers to a section of the road near Bel Air estates just north of UCLA's Drake Stadium where Jan Berry almost died in an automobile accident in 1966.[20] The Buffalo Springfield song "For What It's Worth" was written about a riot at Pandora's Box, a Sunset Strip club, in 1966.[21]

Metro Local lines 2, 175 and 302 operate on Sunset Boulevard. The Metro Red Line operates a subway station at Vermont Avenue.

At 4334 W. Sunset Boulevard, lies the wall featured on the cover of the late singer-songwriter Elliott Smith's 2000 album, Figure 8. Since Elliot's death in 2003, the wall has become a mural for the artist where fans have left many personal messages over the years.

Landmarks include (past and present)

- Amoeba Records

- Beverly Hills Hotel

- Blessed Sacrament Church

- Book Soup

- Carney's

- CBS Columbia Square

- Chateau Marmont

- Cinerama Dome

- Comedy Store

- Crossroads of the World

- Directors Guild of America headquarters

- Dudley Do-Right Emporium

- Earl Carroll Theatre

- The Garden of Allah

- Gower Gulch

- Hollywood Athletic Club

- Hollywood High School

- Hollywood Palladium

- Hotel Bel-Air

- House of Blues

- Hyatt West Hollywood

- KCET

- KTLA

- The London Fog

- Los Angeles Film School

- Metromedia Square (the former Fox Television Center and KTTV studios)

- Nickelodeon on Sunset

- Palisades Charter High School

- Psychiatry: An Industry of Death Museum

- Rainbow Bar and Grill

- Rock Walk

- The Roxy Theatre

- Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine

- Spago

- Standard Hotel

- Sunset Junction

- Sunset Gower Studios

- Tiffany Theatre

- Tiki Ti

- UCLA

- Viper Room

- Whisky a Go Go

- Will Rogers State Beach

- Will Rogers State Historic Park

See also

- Sunset Boulevard (film) (1950)

Notes

- 1 2 Feiler, Bruce (21 September 2010). America's Prophet: How the Story of Moses Shaped America. HarperCollins. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-06-172627-9. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Hawthorne, Christopher (July 14, 2012). "For Sunset, a new dawn". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ↑ Kennelley 1981, p. 69.

- ↑ Kennelley 1981, p. 165.

- ↑ McGroarty, John Steven (1921). Los Angeles from the Mountains to the Sea: With Selected Biography of Actors and Witnesses to the Period of Growth and Achievement, Volume 3. American Historical Society. p. 891. OCLC 920607532.

- ↑ "Board Acts With Favor: Sunset Boulevard May Be Extended: Proposed Improvement Will Cost Hundred Thousand Dollars: Estimates Are Presented to Board of Public Works by Fred Eaton and That Body Grants Petition, for Its Extension—Cost of Widening Bellevue Avenue to a Point Near Plaza". Los Angeles Herald. 28 (4). October 5, 1901. p. 9 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Sunset boulevard at present extends from Hollywood, in the beautiful Cahuenga valley, to Marion avenue. It is now proposed to make Bellevue avenue an extension of the system from Marion avenue to Main street. In order to make the driveway a uniform width It will be necessary to widen Bellevue avenue from seventeen to twenty feet in many places between Marion avenue and the plaza.

- ↑ "Sunset Boulevard May Reach Plaza: City Councilmen Encourage The Extensive Project. Committee of Business Men Secures Favorable Action from the Board of Public Works.". Los Angeles Times. October 5, 1901. p. A2. (subscription required (help)). Alternate Link via ProQuest.

- ↑ "Protest Against Improvement". Los Angeles Herald. 29 (315). August 14, 1902. p. 6 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ↑ "New Boulevard Is Completed: Suburban Residents Will Celebrate Saturday". Los Angeles Herald. 31 (227). May 13, 1904. p. 12 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ↑ "Los Angeles And Hollywood Unite In Opening Of Sunset Boulevard". Los Angeles Herald. 31 (229). May 15, 1904. p. 5 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ↑ 1910 Baist Real Estate Survey Atlas, Los Angeles. Plate 003 (Map). Philadelphia: G. W. Baist. 1910. OCLC 19764849.

- ↑ "Old-day Buildings to Go for Street.". Los Angeles Times. September 17, 1912. p. I7. (subscription required (help)). Alternate Link via ProQuest.

- ↑ Baist Real Estate Survey Atlas, Los Angeles. Plate 003 (Map). Philadelphia: G. W. Baist. 1914.

- ↑ More research is needed to pin down the year

- ↑ Kennelley 1981, p. 219-221.

- ↑ Kennelley 1981, p. 182.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (14 February 2006). Coast of Dreams. Random House. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-679-74072-8. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Ditmore, Melissa Hope (30 August 2006). Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-313-32968-5. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Green, Frank W. M. (5 March 2008). D'Angelico, Master Guitar Builder: What's in a Name?. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-57424-217-1. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Warshaw, Matt (1 September 2010). The History of Surfing. Chronicle Books. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8118-5600-3. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Cecilia (August 5, 2007). "Closing of club ignited the 'Sunset Strip riots'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sunset Boulevard. |

- Libman, Gary (December 18, 1988). "Street of Contrasts in a Changing L.A. : Sunset Boulevard: Epitome of L.A. : As It Winds From Plaza to Ocean, Diversity Is Its Name". Los Angeles Times.