Tamborine Mountain Road

| Tamborine Mountain Road | |

|---|---|

|

Road to Tamborine Mountain, 1931 | |

| Location | Geissmann Drive, North Tamborine, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 27°54′53″S 153°10′39″E / 27.9148°S 153.1776°ECoordinates: 27°54′53″S 153°10′39″E / 27.9148°S 153.1776°E |

| Design period | 1919 - 1930s (interwar period) |

| Built | 1922 - 1925 |

| Official name: Tamborine Mountain Road/Geissmann Drive, Tamborine Station-Tamborine Mountain Road | |

| Type | state heritage (landscape, built) |

| Designated | 5 August 2003 |

| Reference no. | 602365 |

| Significant period | 1920s (fabric) |

| Significant components | embankment - road, culvert - storm water, cutting - road |

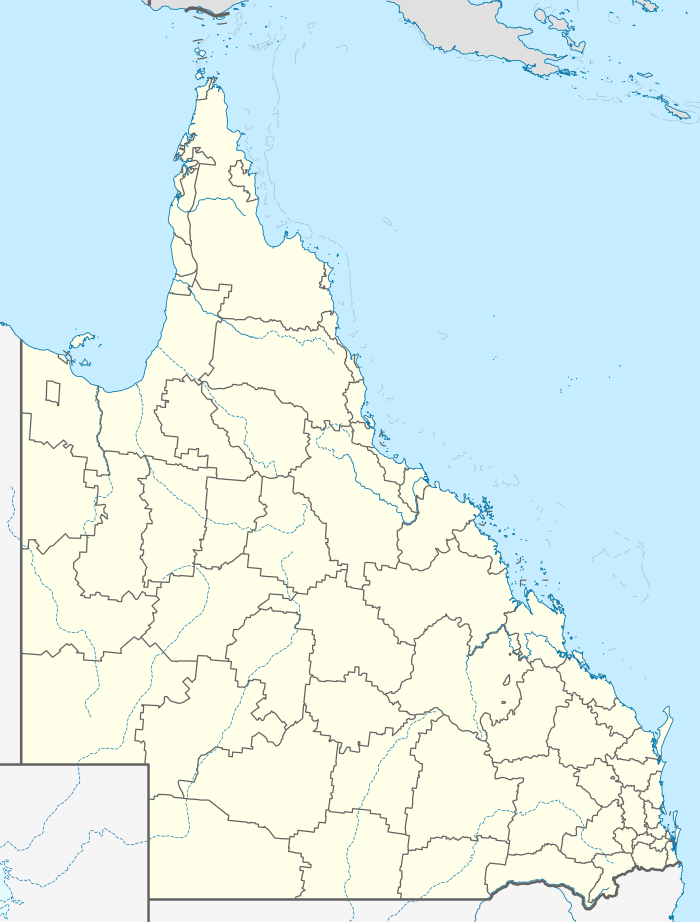

Location of Tamborine Mountain Road in Queensland  Location of Tamborine Mountain Road in Queensland | |

Tamborine Mountain Road is a heritage-listed road at Geissmann Drive, North Tamborine, Queensland, Australia. It was built from 1922 to 1925. It is also known as Tamborine Station-Tamborine Mountain Road and Geissmann Drive. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 5 August 2003.[1]

History

Tamborine Mountain Road was constructed in 1922-1925 to link the small farming community of North Tamborine on the Tamborine Mountain plateau to Tamborine railway station. Linking North Tamborine to the railway system enabled greater tourist access to the mountain, and greater market access for Tamborine Mountain produce. Tamborine Mountain Road was one of the first construction projects undertaken by the newly formed Main Roads Board and was one of the first declared Main Roads and one of the first bitumened roads in Queensland. It remains a main access and tourist road for North Tamborine.[1]

North Tamborine is situated on a plateau 548m in altitude and 10 km by 3.5 km in area, with steep escarpments around most sides with only a few areas where the slope is gentle enough to allow the construction of a road. The first wave of non-indigenous settlers on Tamborine Mountain in the 1870s and 1880s established walking and bridle tracks through the rainforest to reach their selections, where they cleared the land to grow bananas and fruit (and later dairy produce) for the Brisbane markets. Farmers used the same tracks to take their produce down to the valleys. The early track makers had problems with the steep gradients and high rainfall and any track in the area was difficult to make and hard to maintain.[1]

The Tamborine Plateau was recognized early as a tourist and health destination because of its elevation, rain forest vegetation, waterfalls and landscape values. In 1898, the Geissmann family moved to North Tamborine and built a large boarding house, Capo di Monte, and advertised it as a Health Resort. It became very popular and visitors included Lord and Lady Lamington and Sir William MacGregor, Governors of Queensland. Later the house was converted to holiday flats and the family acquired other interests in the area. The Geissmann family was also involved in sawmilling and was very prominent in the area even after Capo di Monte was destroyed by fire in 1932. The upper section of Tamborine Mountain Road was renamed Geissmann Drive about 1982 to honour their contribution to the community.[1]

In July 1918 the Tamborine Mountain Progress Association, anxious to improve access to markets for the increasing number of dairy farmers and fruit growers on the mountain, urged Tamborine Shire Council to construct a good road down the mountain to link North Tamborine with the Tamborine Railway Station. Land was resumed and a route with a reasonable gradient was surveyed in 1920.[1]

The request was timely. By 1920 the need to provide all-weather roads was a priority for all Queenslanders - a response to the increased number of motor vehicles on the roads, and to the need to provide suitable infrastructure for an expanding economy. Queensland roads were in a deplorable condition, the result of haphazard planning by under-funded local authorities. In response, the Queensland Government established the Main Roads Board in 1920 to oversee the construction of connecting roads and bridges and to provide funding to the local authorities involved. The first Board Chairman, JR Kemp, reported that earlier roads failed because they had not been surveyed properly, had too steep gradients, had insufficient drainage for heavy rain areas, had insufficient foundations and carried too heavy loads. These roads often needed expensive maintenance. To reduce the cost of construction and maintenance, Kemp specified standards for the design of road beds, drainage systems, bridge design and other critical areas of road making. In 1925 the Main Roads Board became the Main Roads Commission under JR Kemp as Commissioner and continued the overseeing of road and bridge construction throughout Queensland.[1]

In 1922 a National Main Roads Policy was proclaimed, providing funds for main roads construction on a one for one subsidy basis. Road costs were apportioned as ? Commonwealth funded, 3/8 State and 1/8 local authority. The Commonwealth funding was intended also to provide employment for returned First World War servicemen.[1]

Under the provisions of the Main Roads Act 1920, Tamborine Mountain Road was gazetted on 16 December 1921 as one of Queensland's first seven Main Roads, and the Main Roads Board subsequently made funds available to Tamborine Shire Council for its construction. The Board also specified engineering standards for many aspects of the construction, including road beds, culverts and dry stone rock retaining walls. Some of the retaining walls on the lower side of the road were reputedly 15 feet high. A crushing plant was set up at Sandy Creek in 1923 to provide the road metal, the stone being obtained from a quarry below Curtis Falls.[1]

During 1922-23, its first year of operation, the largest expenditure on permanent road works by the Main Roads Board was on the construction of the Tamborine Mountain Road.[1]

The mountainous upper (southern) part of the road from Sandy Creek to North Tamborine rose to a height of 1800 feet, and was one of the most difficult works undertaken in the period 1922-24. It was completed in 1924 at a cost of £32,158. The road linking Sandy Creek to the Tamborine Railway Station was completed in 1925. Tamborine Shire Council then asked the Main Roads Commission to bitumen the road surface to reduce maintenance costs and this was done. It was one of the first bitumen roads in Queensland. The total cost of the road by 1925 was £42,500.[1]

As funding for the Tamborine Mountain road was partly the responsibility of the local authority, North Tamborine residents in the "benefited area" were levied increased rates. In 1925, the rates increased to 1s 8d in the £, three times that of the surrounding area. This was a hardship for many so in 1930, when changes to the Main Roads Act permitted the levying of tolls on roads with high maintenance costs, Tamborine Shire Council paid £500 to have a toll keeper's house erected at Sandy Creek. Tamborine Mountain Road was one of the first three Queensland main roads/bridges to have a toll imposed under the provisions of the Act. It was anticipated that tolls from tourist vehicles would contribute to the repayments to the local authority but the toll was uneconomic and disliked and was removed in 1945.[1]

Tamborine Mountain Road remained the principal access road to North Tamborine for many years and continues to be a main tourist and access road to the plateau and North Tamborine. The upper (southern) section still winds through subtropical rainforest which for decades has provided an aesthetic portal to the plateau.[1]

The road has had continuous maintenance over its life but still retains many of the original features such as the alignment, culverts and retaining walls.[1]

Description

The Sandy Creek to North Tamborine Mountain section of the Tamborine Mountain Road descends from North Tamborine to the valley to the north west. It is two lanes wide, 7.7 km long, and follows the original alignment. It has been widened in the less steep areas for safety reasons as it is still a major access road, but it retains many of its original features such as culverts, cuttings and rock embankment walls. The alignment includes two large "S" bends, a feature that enabled the road makers to wind up steep pitches while maintaining a gradual gradient. These are not found in modern roads as modern vehicles can climb much steeper gradients. The original bitumen road surface remains, but has been re-surfaced many times.[1]

The Cedar Creek to North Tamborine section traverses very steep hillsides and deep gullies and retains its original alignment with a large "S" bend winding up the hill. As it has a steep gradient, the road has been made by cutting into the hillside and depositing the spoil down hill to make a wider road bed and ease construction problems. Where the cliff has been cut back, some rock walls have been built to stop the bank eroding onto the road and blocking it. Below the road dry stone rock walls, i.e. walls that have no mortar joining the stones, cover the steep embankments to prevent the road surface sliding downhill. To prevent the heavy rainfall washing the road away, culverts under the road direct the water away from the road surface. In some sections these original culverts were not adequate in very heavy rain.[1]

The lower part of the road from Cedar Creek to Sandy Creek traverses more gentle slopes so there are fewer retaining walls, embankments and sharp curves. The road has been widened in several places but it still retains original culverts and walls. It goes through dry sclerophyll forest down to the valley.[1]

Cuttings and embankments are found mainly in the upper section. Many of the embankments are clad in dry stone walling many metres deep and can be seen from the road but many have been covered by the abundant vegetation. Some early dry stone walls can be seen on the upper bank of the road alongside more modern rock walls. One of the original stone embankment walls is found near the Sandy Creek Bridge between the road and the creek. It is about 1.5m high and approximately 16m long and protects the road embankment from erosion from the flooding of Sandy Creek and from road surface run-off.[1]

Twelve culverts were noted and they vary in date and design. They include circular concrete pipes, larger rectangular pipes and modern rectangular section pipes. Some are single, some double depending on the expected water flow. Around each of the inlets is a rock channel and wings to guide the water into the mouth of the pipe and these have been individually designed for the particular site. Many have concrete end walls and loose concrete added to the surface. On the outlet side there is mostly a rock surround around the pipe and, if space, a concrete apron to prevent erosion. As with any functional road, there is evidence of a continuous upgrade of surface and culverts as required for safety but many of the original culverts survive.[1]

The roadside vegetation is dry sclerophyll for much of its length changing to subtropical vine rainforest in the upper areas. This rainforest area with the Bangalow Palms in Cedar Creek Valley has retained its original characteristics and forms an important part of the landscape of this site. Another feature of the road reserve is the Sentinel, a piece of basalt, standing beside the upper S bend. It has stood beside the road since its construction as part of a larger bolder, too heavy to move, and as such has become a local landmark.[1]

Heritage listing

Tamborine Mountain Road/Geissmann Drive was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 5 August 2003 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history.

The road is important historically as it was one of the first Main Roads in Queensland gazetted by the Main Roads Board. The road demonstrates achievement in road building in difficult terrain in the 1920s and the early use of asphaltic concrete as a road surface. It also demonstrates the application of scientific and engineering standardized approaches to road construction as advocated by the first Main Roads Board, to reduce costs and produce better roads. The road is important also in demonstrating the success of the co-operative effort of a small community to improve their means of access, and is significant for its contribution to the development of Tamborine Mountain farming and tourism.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a particular class of cultural places.

Tamborine Mountain Road has survived with a number of original elements, including 1920s culverts and rock walls. These demonstrate the principal characteristics of the Main Roads Board's standardized requirements for the construction of important early Queensland roads. These elements are particularly evident in the upper one third of the road.[1]

The place is important because of its aesthetic significance.

This upper section (Geissmann Drive), which winds through subtropical rainforest and which for decades has provided an aesthetic portal to the plateau, is valued by local residents and tourists alike for its aesthetic qualities. It is from the Tamborine Mountain Road approach that most visitors, since the 1920s, have obtained their first experience of the mountain's subtropical rainforest environment, which is highly valued for its natural heritage qualities.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The place is important to the community for its continuing social and cultural connections. In renaming the upper (southern) part of the road as Geissmann Drive, the local community has honoured the work of the pioneering Geissmann family, early guesthouse owners and sawmillers who did much to promote Tamborine as a health resort and tourist destination and were active in the local community for many years.[1]

References

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).