Tartuffe

| Tartuffe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Written by | Molière |

| Date premiered | 1664 |

| Original language | French |

| Genre | Comedy |

| Setting | Orgon's house in Paris, 1660s |

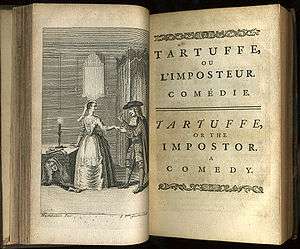

Tartuffe, or The Impostor, or The Hypocrite (/tɑːrˈtʊf, -ˈtuːf/;[1] French: Tartuffe, ou l'Imposteur, pronounced: [taʁtyf u lɛ̃pɔstœʁ]), first performed in 1664, is one of the most famous theatrical comedies by Molière. The characters of Tartuffe, Elmire, and Orgon are considered among the greatest classical theatre roles.

History

Molière wrote Tartuffe in 1664. Almost immediately following its first performance that same year at the Versailles fêtes, it was censored by King Louis XIV, probably due to the influence of the archbishop of Paris, Paul Philippe Hardouin de Beaumont de Péréfixe, who was the King's confessor and had been his tutor.[2] While the king had little personal interest in suppressing the play, he did so because, as stated in the official account of the fête:

"...although it was found to be extremely diverting, the king recognized so much conformity between those that a true devotion leads on the path to heaven and those that a vain ostentation of some good works does not prevent from committing some bad ones, that his extreme delicacy to religious matters can not suffer this resemblance of vice to virtue, which could be mistaken for each other; although one does not doubt the good intentions of the author, even so he forbids it in public, and deprived himself of this pleasure, in order not to allow it to be abused by others, less capable of making a just discernment of it."[3]

As a result of Molière's play, contemporary French and English both use the word "tartuffe" to designate a hypocrite who ostensibly and exaggeratedly feigns virtue, especially religious virtue. The play is written entirely in 1,962 twelve-syllable lines (alexandrines) of rhyming couplets.[4]

Characters

| Character | Description |

|---|---|

| Orgon | Head of the house and husband of Elmire, he is blinded by admiration for Tartuffe. |

| Tartuffe | Houseguest of Orgon, hypocritical religious devotee who attempts to seduce Elmire and foil Valère's romantic quest. |

| Valère | The young romantic lead, who struggles to win the hand of his true love, Orgon's daughter Mariane. |

| Madame Pernelle | Mother of Orgon; grandmother of Damis and Mariane |

| Elmire | Wife of Orgon, step-mother of Damis and Mariane |

| Dorine | Family housemaid, who tries to help expose Tartuffe and help Valère. |

| Cléante | Brother of Elmire, brother-in-law of Orgon |

| Mariane | Daughter of Orgon, the fiancée of Valère and sister of Damis |

| Damis | Son of Orgon; and brother of Mariane |

| Laurent | Servant of Tartuffe (non-speaking character) |

| Argas | Friend of Orgon who was anti-Louis XIV during the Fronde (mentioned but not seen). |

| Flipote | Servant of Madame Pernelle (non-speaking character) |

| Monsieur Loyal | A bailiff |

| A King's Officer/The Exempt | An officer of the king |

Plot

Orgon's family is up in arms because Orgon and his mother have fallen under the influence of Tartuffe, a pious fraud (and a vagrant prior to Orgon's help). Tartuffe pretends to be pious and to speak with divine authority, and Orgon and his mother no longer take any action without first consulting him.

Tartuffe's antics do not fool the rest of the family or their friends; they detest him. Orgon raises the stakes when he announces that he will marry Tartuffe to his daughter Mariane (already engaged to Valère). Mariane, of course, feels very upset at this news, and the rest of the family realizes how deeply Tartuffe has embedded himself into the family.

In an effort to show Orgon how awful Tartuffe really is, the family devises a scheme to trap Tartuffe into confessing to Elmire his desire for her. As a pious man and a guest, he should have no such feelings for the lady of the house, and the family hopes that after such a confession, Orgon will throw Tartuffe out of the house. Indeed, Tartuffe does try to seduce Elmire, but their interview is interrupted when Orgon's son Damis, who has been eavesdropping, is no longer able to control his boiling indignation and jumps out of his hiding place to denounce Tartuffe.

Tartuffe is at first shocked but recovers very well. When Orgon enters the room and Damis triumphantly tells him what happened, Tartuffe uses reverse psychology and accuses himself of being the worst sinner:

- Oui, mon frère, je suis un méchant, un coupable.

- Un malheureux pécheur tout plein d'iniquité

- (Yes, my brother, I am a sinner, a guilty man,

- An unhappy sinner full of iniquity) (III.vi).

Orgon is convinced that Damis was lying and banishes him from the house. Tartuffe even gets Orgon to order that, to teach Damis a lesson, Tartuffe should be around Elmire more than ever. As a gift to Tartuffe and further punishment to Damis and the rest of his family, Orgon signs over all his worldly possessions to Tartuffe.

In a later scene, Elmire takes up the charge again and challenges Orgon to be witness to a meeting between herself and Tartuffe. Orgon, ever easily convinced, decides to hide under a table in the same room, confident that Elmire is wrong. He overhears, of course, Elmire resisting Tartuffe's very forward advances. When Tartuffe has incriminated himself beyond all help and is dangerously close to violating Elmire, Orgon comes out from under the table and orders Tartuffe out of his house.

But this wily guest means to stay, and Tartuffe finally shows his hand. It turns out that earlier, before the events of the play, Orgon had admitted to Tartuffe that he had possession of a box of incriminating letters (written by a friend, not by him). Tartuffe had taken charge and possession of this box, and now tells Orgon that he (Orgon) will be the one to leave. Tartuffe takes his temporary leave and Orgon's family tries to figure out what to do. Very soon, Monsieur Loyal shows up with a message from Tartuffe and the court itself – they must move out from the house because it now belongs to Tartuffe. Dorine makes fun of Monsieur Loyal's name, mocking his fake loyalty. Even Madame Pernelle, who had refused to believe any ill about Tartuffe even in the face of her son's actually seeing it, has become convinced by this time of Tartuffe's duplicity.

No sooner does Monsieur Loyal leave than Valère rushes in with the news that Tartuffe has denounced Orgon for aiding and assisting a traitor by keeping the incriminating letters and that Orgon is about to be arrested. Before Orgon can flee, Tartuffe arrives with an officer, but to his surprise the officer arrests him instead. The officer explains that the enlightened King Louis XIV—who is not mentioned by name—has heard of the injustices happening in the house and, appalled by Tartuffe's treachery towards Orgon, has ordered Tartuffe's arrest instead; it turns out that Tartuffe has a long criminal history and has often changed his name to avoid being caught. As a reward for Orgon's previous good services, the King not only forgives him for keeping the letters but also invalidates the deed that gave Tartuffe possession of the house and all Orgon's possessions. The entire family thanks its lucky stars that it has escaped the mortification of both Orgon's potential disgrace and their dispossession. The drama ends well, and Orgon announces the upcoming wedding of Valère and Mariane. The surprise twist ending, in which everything is set right by the unexpected benevolent intervention of the heretofore unseen King, is considered a notable modern-day example of the classical theatrical plot device Deus ex machina.

Controversy

Though Tartuffe was received well by the public and even by Louis XIV, it immediately sparked conflict amongst many different groups who were offended by the play. The factions opposed to Molière's work included part of the hierarchy of the French Roman Catholic Church, members of upper-class French society, and the illegal underground organization called the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement. Tartuffe's popularity was cut short when the Archbishop of Paris issued an edict threatening excommunication for anyone who watched, performed in, or read the play. Molière attempted to assuage church officials by re-writing his play to seem more secular and less critical of religion, but the church could not be budged. The revised version of the play was called L'Imposteur and had a main character titled Panulphe instead of Tartuffe. Even throughout Molière's conflict with the church, Louis XIV continued to support the playwright; it is possible that without the King's support, Molière might have been excommunicated. Although public performances of the play were banned, private performances for the French aristocracy were permitted.[5] In 1669, after Molière's detractors lost much of their influence, he was finally allowed to perform the final version of his play. However, due to all the controversy surrounding Tartuffe, Molière mostly refrained from writing such incisive plays as this one again.[6]

Molière responded to criticism of Tartuffe in 1667 with his Lettre sur la comédie de l'Imposteur. He sought to justify his play and his approach to comedy in general by underlining the comedic value of the juxtaposition of good and bad, right and wrong, and wisdom and folly. These humorous elements in turn were intended to highlight what is actually rational. In his Lettre he wrote:

| “ | The comic is the outward and visible form that nature's bounty has attached to everything unreasonable, so that we should see, and avoid, it. To know the comic we must know the rational, of which it denotes the absence and we must see wherein the rational consists . . . incongruity is the heart of the comic . . . it follows that all lying, disguise, cheating, dissimulation, all outward show different from the reality, all contradiction in fact between actions that proceed from a single source, all this is in essence comic.[7] | ” |

Production history

The original version of the play was in three acts and was first staged on 12 May 1664 as part of festivities known as Les Plaisirs de l'île enchantée held at the Palace of Versailles. Because of the attacks on the play and the ban that was placed on it, this version was never published, and no text has survived, giving rise to much speculation as to whether it was a work in progress or a finished piece. Many writers believe it consisted of the first three acts of the final version, while John Cairncross has proposed that acts 1, 3, and 4 were performed.[8] Although the original version could not be played publicly, it could be given privately,[8] and it was seen on 25 September 1664 in Villers-Cotterêts and 29 November 1664 at the Château du Raincy.[9]

The first revised version, L'Imposteur, was in five acts and was performed only once, on 5 August 1667 in the Théâtre du Palais-Royal. On 11 August, before any additional performances, this version was also banned. The final revised version in five acts, under the title Le Tartuffe, began on 5 February 1669 at the Palais-Royal theatre and was highly successful.[8] This version was published[10] and is the one that is generally performed today.[8]

Modern productions

The seminal Russian theatre practitioner Constantin Stanislavski was working on a production of Tartuffe when he died in 1938. It was completed by Mikhail Kedrov and opened on 4 December 1939.[11]

The first Broadway production took place at the ANTA Washington Square Theatre in New York and ran from 14 January 1965 to 22 May 1965. The cast included Hal Holbrook as "M. Loyal", John Phillip Law as "King's Officer", Laurence Luckinbill as "Damis" and Tony Lo Bianco as "Sergeant".

The National Theatre Company performed a production in 1967 using the Richard Wilbur translation and featuring Sir John Gielgud as Orgon, Robert Stephens as Tartuffe, Jeremy Brett as Valere, Derek Jacobi as The Officer and Joan Plowright as Dorine.[12]

A production of Richard Wilbur's translation of the play opened at the Circle in the Square Theatre in 1977 and was re-staged for television the following year on PBS, with Donald Moffat replacing John Wood as Tartuffe, and co-starring Tammy Grimes and Patricia Elliott.

Tartuffe has been performed a number of times at the Stratford Festival in Ontario, Canada first in 1968 with a production by the Stratford National Theatre of Canada using the Richard Wilbur translation and directed by Jean Gascon; the cast included Douglas Rain as Orgon and William Hutt as Tartuffe. The play has since been revived at the Festival in 1969, 1983, 1984 and 2000.

Simon Gray's adaptation was first performed at The Kennedy Center, Washington D.C., in May 1982, starring Barnard Hughes, Carole Shelley, Fritz Weaver and Brian Bedford.

In 1983, a Royal Shakespeare Company production directed by Bill Alexander used the translation by Christopher Hampton. Staged at The Pit in the Barbican Centre, London, the cast included Antony Sher as Tartuffe, Alison Steadman as Elmire, Mark Rylance as Damis and Nigel Hawthorne as Orgon. This production was later videotaped for television.

Another production at the Circle in the Square Theatre, entitled Tartuffe: Born Again, ran from 7 May to 23 June 1996 (a total of 25 previews and 29 performances). This was set in a religious television studio in Baton Rouge where the characters cavort to either prevent or aid Tartuffe in his machinations. Written in modern verse, Tartuffe: Born Again adhered closely to the structure and form of the original. The cast included John Glover as "Tartuffe" (described in the credits as "a deposed televangelist"), Alison Fraser as "Dorine" (described in the credits as "the Floor Manager") and David Schramm as "Orgon" (described in the credits as "the owner of the TV studio").

The most recent Broadway production took place at the American Airlines Theatre and ran from 6 December 2002 until 23 February 2003 (a total of 40 previews and 53 performances). The cast included Brian Bedford as "Orgon", Henry Goodman as "Tartuffe" and Bryce Dallas Howard as "Mariane".

The Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh staged a Scots version by Liz Lochhead in 1987, which it revived on 7 January 2006.

The Tara Arts theatre company performed a version at the National Theatre in London in 1990. Performed in English, the play was treated in the manner of Indian theatre; it was set in the court of Aurangazeb and began with a salam in Urdu.

A translation by Ranjit Bolt was staged at London's Playhouse Theatre in 1991 with Abigail Cruttenden, Paul Eddington, Jamie Glover, Felicity Kendal, Nicholas Le Prevost, John Sessions and Toby Stephens.[13]

Ranjit Bolt's translation was also staged at the National in 2002 with Margaret Tyzack as Madame Pernelle, Martin Clunes as Tartuffe, Clare Holman as Elmire, Julian Wadham as Cleante and David Threlfall as Orgon.[14]

David Ball adapted Tartuffe for the Theatre de la Jeune Lune in 2006. Dominique Serrand revived this production in 2015 in a coproduction with Berkeley Repertory Theatre, South Coast Repertory and the Shakespeare Theatre Company.[15]

Liverpudlian poet Roger McGough's translation premièred at the Liverpool Playhouse in May 2008 and transferred subsequently to the Rose Theatre, Kingston.[16]

Gordon C. Bennett and Dana Priest published a new adaptation, Tartuffe--and all that Jazz! in 2013 with www.HeartlandPlays.com set in 1927 St. Louis, the era of jazz and Prohibition, both of which figure into the plot. The play contains the original Tartuffe characters plus a few new ones in keeping with the altered scenario and a surprise ending to the hypocrite's machinations. The authors have created their own rhymed verse in the Molière tradition.

In October 2013, The National Arts Centre of Canada puts on a performance of Tartuffe set in 1939 Newfoundland.

In May 2014, the play was performed at the Ateliers Berthier theater in Paris, France.

In July/August 2014, Tartuffe was performed by Bell Shakespeare Company with a modern Australian twist, translated from original French by Justin Fleming, at the Sydney Opera House Drama Theatre and earlier at the Melbourne Theatre Company in 2008, with uniquely varied rhyming verse forms.

Adaptations

Film

- The film Herr Tartüff was produced by Ufa in 1926. It was directed by F. W. Murnau and starred Emil Jannings as Tartuffe, Lil Dagover as Elmire and Werner Krauss as Orgon.

- Gérard Depardieu directed and starred in the title role of a 1984 French film version.

- The 2007 French film Molière contains many references, both direct and indirect, to Tartuffe, the most notable of which is that the character of Molière masquerades as a priest and calls himself "Tartuffe". The end of the film implies that Molière went on to write Tartuffe based on his experiences in the film.

Stage

- Eldridge Publishing published Tartuffe in Texas, with a Dallas setting, in 2012. http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=2212

- Bell Shakespeare Company, Tartuffe - The Hypocrite translated from original French by Justin Fleming in 2014 and earlier for Melbourne Theatre Company in 2008, with uniquely varied rhyming verse forms.

- American Stage Theatre Company (http://americanstage.org/) in St. Petersburg, Fla.) adapted Tartuffe in 2016, staged in modern day as a political satire, with Orgon, as a wealthy American businessman who entrusts his reputation and his fortune to up-and-coming politician, Tartuffe.

http://americanstage.org/tartuffe/

Television

- Productions for French television were filmed in 1971, 1975, 1980, 1983 and 1998.

- On 28 November 1971, the BBC broadcast as part of their Play of the Month series a production directed by Basil Coleman using the Richard Wilbur translation and featuring Michael Hordern as Tartuffe, Mary Morris as Madame Pernelle and Patricia Routledge as Dorine.[17]

- Donald Moffat starred in a 1978 videotaped PBS television production with Stefan Gierasch as Orgon, Tammy Grimes as Elmire, Ray Wise as Damis, Victor Garber as Valère and Geraldine Fitzgerald as Madame Pernelle. The translation was by Richard Wilbur and the production was directed by Kirk Browning. Taped in a television studio without an audience, it originated at the Circle in the Square Theatre in New York in 1977, but with a slightly different cast – John Wood played Tartuffe in the Broadway version, and Madame Pernelle was played by Mildred Dunnock in that same production.

- The BBC adapted the Bill Alexander production for the Royal Shakespeare Company. This television version was first screened in the UK during November 1985 in the Theatre Night series with Antony Sher, Nigel Hawthorne and Alison Steadman reprising their stage roles (see "Modern Productions" above).[18]

Opera

- The composer Kirke Mechem based his opera Tartuffe on the play.

Audio

- In 1968, Caedmon Records recorded and released on LP (TRS 332) a production performed that same year by the Stratford National Theatre of Canada as part of the Stratford Festival (see "Stratford Shakespeare Festival production history") using the Richard Wilbur translation and directed by Jean Gascon. The cast included Douglas Rain as Orgon and William Hutt as Tartuffe.

- In 2009, BBC Radio 3 broadcast an adaptation directed by Gemma Bodinetz and translated by Roger McGough, based on the 2008 Liverpool Playhouse production (see "Modern Productions" above), with John Ramm as Tartuffe, Joseph Alessi as Orgon, Simon Coates as Cleante, Annabelle Dowler as Dorine, Rebecca Lacey as Elmire, Robert Hastie as Damis and Emily Pithon as Marianne.[19]

- L.A. Theatre Works performed and recorded a production in 2010 (ISBN 1-58081-777-7) with the Richard Wilbur translation and featuring Brian Bedford as Tartuffe, Martin Jarvis as Orgon. Alex Kingston as Elmire and John de Lancie as Cleante.

References

- ↑ "Tartuffe". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ Molière et le roi, François Rey & Jean Lacouture, éditions du seuil, 2007

- ↑ Molière et le roi, François Rey & Jean Lacouture, éditions du seuil, 2007, p76

- ↑ Molière, Tartuffe trans. Martin Sorrel, Nick Hern Books, London, 2002,

- ↑ Pitts, Vincent J. (2000). La Grande Mademoiselle at the Court of France: 1627—1693. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 250. ISBN 0-8018-6466-6.

- ↑ "Molière: Introduction." Drama Criticism. Ed. Linda Pavlovski, Editor. Vol. 13. Gale Group, Inc., 2001. eNotes.com. 2006. accessed 26 November 2007

- ↑ "Molière." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. accessed 4 December 2007

- 1 2 3 4 Koppisch 2002.

- ↑ Garreau 1984, vol. 3, p. 417.

- ↑ Molière 1669.

- ↑ Benedetti (1999, 389).

- ↑ http://theatricalia.com/play/3sz/tartuffe/production/a74

- ↑ http://theatricalia.com/play/3sz/tartuffe/production/ctx

- ↑ http://theatricalia.com/play/3sz/tartuffe/production/skh

- ↑ http://www.berkeleyrep.org/press/pr/1415/Berkeley_Rep_Tartuffe.pdf

- ↑ Philip Key Tartuffe, Roger McGough, Liverpool Playhouse Liverpool Daily Post (15 May 2008)

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0067826/?ref_=fn_tt_tt_13

- ↑ While this television version does derive from the RSC's 1983 stage production, IMDb is inaccurate in dating this videotaped version from that year. The BFI Film & TV Database indicates the start date for this programme's production was in 1984, while the copyright date is for 1985. See the BFI Film & TV Database outline page and the linked pages.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00lfp66

Sources

- Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-52520-1.

- Garreau, Joseph E. (1984). "Molière", vol. 3, pp. 397–418, in McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama, Stanley Hochman, editor in chief. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070791695.

- Koppisch, Michael S. (2002). "Tartuffe, Le, ou l'Imposteur", pp. 450–456, in The Molière Encyclopedia, edited by James F. Gaines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313312557.

- Molière (1669). Le Tartuffe ou l'Imposteur. Paris: Jean Ribov. Copy at Gallica.

- Brockett, Oscar. 1964. "THE THEATER, an Introduction" published Holt, Rhinehart,and Winston. Inclusive of University of Iowa production, "Tartuffe", includes "The Set Designer", set design and Thesis, a three hundred year commemoration, "A Project In Scene Design and Stage Lighting for Moliere's Tartuffe", by Charles M. Watson, State University of Iowa, 1964.

- "The Misanthrope and Tartuffe" by Molière, and Richard Wilbur 1965, 1993. A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York, NY.

- "The Misanthrope, Tartuffe, and other Plays", by Molière, and Maya Slater 2001, Oxfords World Classics, Oxford University Press, Clays Ltd. 2008

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tartuffe. |

- Free Project Gutenberg etext of Tartuffe (in modern English verse)

- Tartuffe (original version) with approx. 1000 English annotations at Tailored Texts