Tatamagouche

| Tatamagouche | |

|---|---|

| Village | |

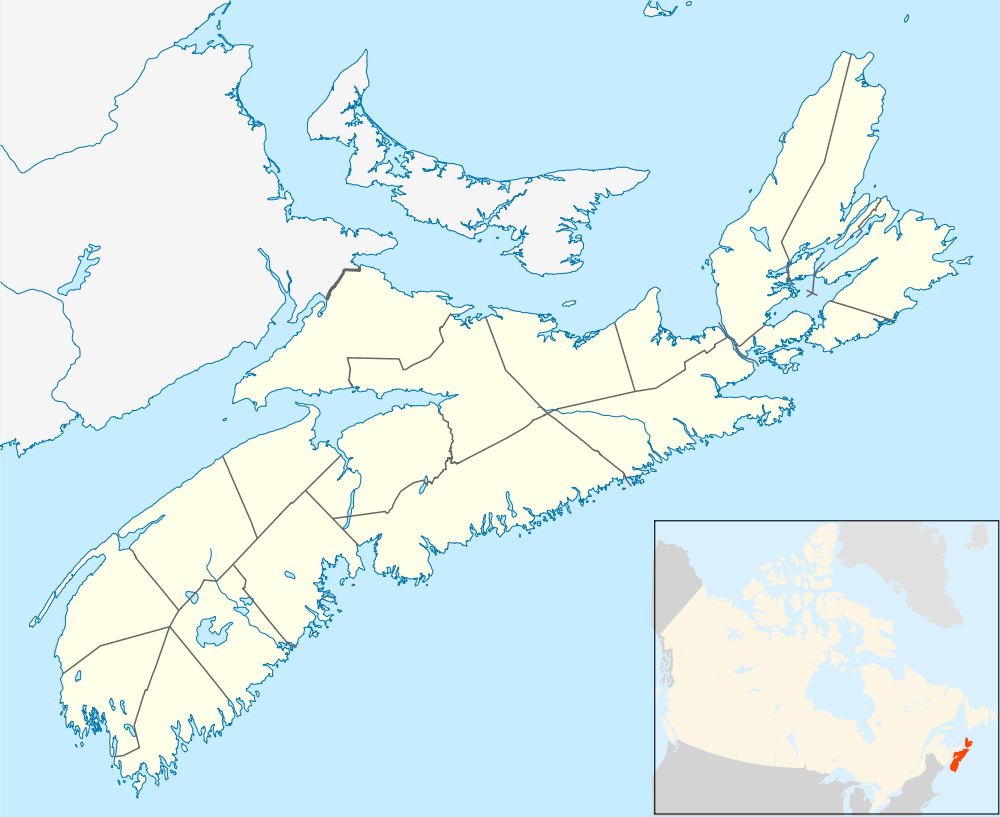

Tatamagouche Location of Tatamagouche in Nova Scotia | |

| Coordinates: 45°42′43″N 63°17′28″W / 45.71194°N 63.29111°W | |

| Country |

|

| Province |

|

| County | Colchester |

| Electoral Districts Federal |

Cumberland—Colchester—Musquodoboit Valley |

| Provincial | Colchester North |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,037 |

| Time zone | AST (UTC-4) |

| • Summer (DST) | ADT (UTC-3) |

Tatamagouche /ˌtætəməˈɡʊʃ/ is a village in Colchester County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Tatamagouche is situated on the Northumberland Strait 50 kilometres north of Truro and 50 kilometres west of Pictou. The village is located along the south side of Tatamagouche Bay at the mouths of the French and Waugh Rivers. Tatamagouche derives its name from the native Mi'kmaq term Takǔmegoochk, roughly translated as "extending across".[2]

Early history

The first European settlers in the Tatamagouche area were the French Acadians, who settled the area in the early18th century, and Tatamagouche became a transshipment point for goods bound for Fortress of Louisbourg.

Battle at Tatamagouche

During King George's War, New England was engaged in the Siege of Louisbourg (1745) in their efforts to defeat the French. On June 15, 1745, Captain Donahew confronted Lieut. Paul Marin de la Malgue's allied force who was en route from Annapolis Royal to Louisbourg.[3] The French convoy of two sloops and two schooners and many natives in a large number of canoes was a relief effort of French and Mi'kmaq on their way to the fortress. Donahew drove the French ashore, preventing supplies and reinforcements from reaching Louisbourg before it fell to the English. The British reported there was a "considerable slaughter" of the French and natives.[4] The battle was significant in the downfall of Louisbourg because Marin's relief envoy was thwarted.[5]

Expulsion of the Acadians

The homes of the Acadians who lived in the village were burned as part of the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755) during the French and Indian War. Tatamagouche and nearby Wallace, Nova Scotia were the first villages in Acadia to be burned because they were the gateway through which Acadians supplied the French Fortress Louisbourg.

All that remains from that period are Acadian dykes and some French place names.

Fort Franklin was built at Tatamagouche in 1768, named after Michael Francklin.[6][7] (The fort was built immediately after the abandonment of both Fort Ellis (Nova Scotia) and Fort Belcher.)

New England Planters

Ten years later, on August 25, 1765, the land that became Tatamagouche was given to British military mapmaker Colonel Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres by the British Crown. DesBarres was awarded 20,000 acres (81 km2) of land in and around Tatamagouche on the condition that he settle it with 100 Protestants within 10 years. Low land prices in other colonies made attracting tenants difficult, but an offer of six years free rent to dissatisfied residents of Lunenburg was a moderate success (1772). Protestant repopulation also grew considerably before the end of the century with a flood of Scottish immigrants following the Highland Clearances.

Ship building and lumbering

In the 19th century, like many other villages in the area, Tatamagouche had a sizable shipbuilding industry. Trees were plentiful and sawmills started appearing on area rivers, producing lumber for settlers. Builders needed the lumber to produce the ships and it was common to send a completed vessel overseas loaded with lumber.

Generally, there were five types of vessels being built at Tatamagouche: the schooner, brig, brigantine, barque, and clipper ship. Of these, schooners were by far the most popular. There is also one barquentine on record as being built at Tatamagouche, the Yolande in 1883.

Many of the larger vessels, such as the brigs, barques and brigantines, were loaded with lumber from the area and sailed to Britain, where first the cargo, and then the ship itself, were sold. Some of the ships sold immediately, while others could take years to find a buyer. Often, the owner would sail the ship over to arrange for its sale personally, other times they would be sold through a firm such as Cannon, Miller, & Co., who sold most of the Campbell brothers ships.

The age of steam ended ship building in Tatamagouche.

The Campbell Brothers

On May 17, 1824, Alexander Campbell and partners William Mortimer and G. Smith launched their first ship on the French river, a 63-foot (19 m) schooner named Elizabeth. They launched several more ships together, until Alexander went into partnership with his brothers, William and James, in 1830. Their partnership ended in 1833 following a disagreement between Alexander and James. The brothers went their separate ways, each building ships for some time afterwards, but the list of ships built in Tatamagouche shows Alexander Campbell to be the most active of the three, with over 70 ships to his name.

William built about a dozen ships after the breakup that varied in quality, size and type. Several of them were loaded with timber bound for the British Isles. His last ship was the Trident and in 1842 she ran aground off Newfoundland on her maiden voyage, leaving him near bankruptcy. He died a poor man in 1878, despite having held several other jobs.

When William stopped building, Alexander took over his yard and attacked the market in full force. At the height of the ship building days he employed about 200 men. In 1850 he turned out eight ships.

Railroad

.jpg)

The Intercolonial Railway constructed its "Short Line" from Oxford Junction to Stellarton through Tatamagouche in 1887. The ICR commissioned the Rhodes Curry Company of Amherst to build a passenger station in the village immediately east of the creamery. The ICR was merged into the Canadian National Railways in 1918 and CN operated this line as part of its "Oxford Subdivision", servicing mainly agricultural communities, as well as the salt mines at Malagash and Pugwash as well as a quarry in Wallace. Passenger service through Tatamagouche was discontinued in the 1960s and the station was used as an office for railway employees handling freight until 1972 when it was closed and sold in 1976. CN discontinued freight service on the line in 1986 when the Oxford Sub was abandoned; the rails were removed in 1989.

Today the passenger station is a bed and breakfast with restored historic rail cars located on the property. The rail line through the village is a recreational trail, designated as part of the Trans Canada Trail and the point where the Nova Scotia portion of the trail branches south to Truro, Halifax and southwestern Nova Scotia, making Tatamagouche a good starting point for a short waterfront walk or a major biking expedition.

Landmarks and attractions

- One of the most famous landmarks in the village is the Tatamagouche Creamery, begun by Alexander Ross in 1925. Over 1000 local farms supplied milk to the Creamery in order to produce its famous Tatamagouche Butter, which it did daily, making almost 2,000 lb (910 kg). In 1930, J. J. Creighton purchased the Creamery. After his death in 1967, Scotsburn Dairy Cooperative acquired it. Scotsburn kept the Creamery operational from 1968 until they closed its doors in 1992. The 1-acre (4,000 m2) lot and two buildings were donated to the village with the stipulation that no structural changes were to be made to the building’s exterior, including the name and colour. However, a community cannot hold a deed, so the Creamery Society, a community-based organization, was formed to take over the building. The Creamery Square Association was formed to develop the Creamery Square project. A new Farmers' Market building opened in May 2006, and the Creamery building is now home to The North Shore Archives and the Giantess Anna Swan Museum. The Sunrise Trail Museum and Brule Fossil Centre will be components of this new heritage development.

- The principal historical museum in the area for many years was the Sunrise Trail Museum, but the building has been sold and exhibits have been moved to the Creamery Square complex.

- The Barrachois Harbour Yacht Club at Sunrise Shore Marina just east of Tatamagouche offers excellent cruising and racing programs as well as online resources for powerboats and sailing vessels. The Earle W. Forshner Memorial regatta takes place on Labour Day weekend subject to tide constraints. The Club maintains several mooring buoys just north of the entrance to Barrachois channel as well as to the east of Malagash Point for cruising vessels. If not occupied by club vessels, transient boaters are more than welcome to use them. Beware however, these are exposed to the northeast. It would be unwise to overnight there in northeasterly winds.

- The Fraser Cultural Centre acts as a visitor information centre, art gallery, and has an exhibition about the "Nova Scotia Giantess" Anna Swan.

- On the last weekend of September each year, the Bavarian Society of Tatamagouche hosts the second largest Oktoberfest in Canada.

- The Sutherland Steam Mill Museum is in the nearby village of Denmark.

- Dorje Denma Ling, a retreat centre in the Shambhala Buddhist tradition in The Falls (10 km south of the village) attracts visitors from around the world.

- The Tatamagouche Centre is an accredited, non-profit education, conference and retreat centre of the United Church of Canada.

Events

In September 2008, Paperny Films of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada selected Tatamagouche as the venue for the second (and last) season of The Week the Women Went. The episodes aired on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, (CBC). The first episode went to air on January 21, 2009.

References

- ↑ "Browse Data by Community Profile, 2011 and 2006 censuses (Nova Scotia)". Government of Nova Scotia. December 18, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ↑ Rand, Silas Tertius (1875-01-01). A First Reading Book in the Micmac Language: Comprising the Micmac Numerals, and the Names of the Different Kinds of Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Trees, &c. of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Also, Some of the Indian Names of Places, and Many Familiar Words and Phrases, Translated Literally Into English. Nova Scotia Printing Company.

- ↑ The Historical magazine, and notes and queries concerning the antiquities, 1870. p. 24; .

- ↑ Ralph M. Eastman. "Captain Noah Stoddard" in Some Famous Privateers of New England. 1928. p. 68

- ↑ Patterson, pp.16-18; Note that Murdock erroneously locates this battle of Cape Sable. Duchambon at Louisbourg distinctly stated that Marin's failure to appear proved disastrous to him at a time when succor would have meant victory (See William Pote's journal, p. xxvii).

- ↑ Frank Patterson. Acadian Tatamagouche and Fort Franklkin, p.75

- ↑ ojs.library.dal.ca/NSM/article/download/4075/3730

- Texts

- Acadians at Tatamagouche by Patterson

- Frank Harris Patterson. History of Tatamagouche. Halifax: Royal Print & Litho., 1917 (also Mika, Belleville: 1973).

- Patterson,Frank. A History of Tatamagouche

External links

Media related to Tatamagouche at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tatamagouche at Wikimedia Commons- Dorje Denma Link Retreat.

- Village of Tatamagouche Link.

|

Wallace, Nova Scotia Via |

| ||

| Wentworth, Nova Scotia Via |

|

River John, Nova Scotia Via | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Truro, Nova Scotia Via |

Coordinates: 45°43′N 63°17′W / 45.717°N 63.283°W