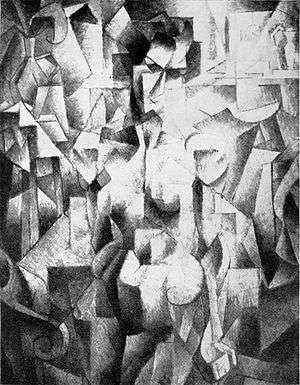

The Accordionist

| Artist | Pablo Picasso |

|---|---|

| Year | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 130.2 cm × 89.5 cm ( 51 1⁄4 in × 35 1⁄4 in) |

| Location | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, United States |

| Accession | 37.537 |

The Accordionist is a 1911 painting by Pablo Picasso. As stated by the title, the painting is meant to portray a man playing an accordion. The division of three-dimensional forms into a two-dimensional plane indicate that the painting is in the style of analytic cubism,[1] which was developed by Picasso and Georges Braque between 1907 and 1914. The onset of cubism is possibly due to Picasso and Braque rebelling against centuries of traditional, realistic art that imitates the natural world.

In earlier stages of analytic cubism, such as Picasso's Carafe, Jug and Fruit Bowl, Picasso begins to break up the subject matter and alter the sense of depth. However, in earlier work there is still a defined sense of the subject's shape and volume. The picture plane is distorted, but not to the same extent as later paintings such as The Accordionist which verge on complete abstraction. Also differentiating early and late analytical cubism is the use of color. In Carafe, Jug and Fruit Bowl Picasso uses color to define the table cloth, bowls, and fruit, allowing the viewer to easily discern the subject matter, despite the slight flattening and separation of the picture plane. The Accordionist on the other hand is almost monochromatic which further camouflages the subject.

The painting

The Accordionist is 51.25 inches tall and 35.25 inches wide, painted in oil on canvas.[2] The composition consists of a multitude of geometric shapes of various sizes and content. The shapes most densely populate the middle of the painting, fanning out in a kind of triangle shape from the top to the bottom of the painting. Since there is no obvious subject, this composition leads the viewer’s eye around the painting in an attempt to decipher the content.

Also focused toward the center of the painting are the dark colors, which aid in drawing the viewer in to explore the painting. Picasso utilized the drab, muted tones[3] in order to place the emphasis on the subject. Picasso’s dull palette also lends itself well to the piecing together of the different perspectives of the same subject.

Interpretation

In the top middle portion of the painting there is a cluster of curvaceous shapes. Theses shapes seem to form the face of the accordion player, which then leads down to the player’s body that expands out from neck to shoulders to the rest of the body. Following the face down the painting, there is a large right angle that protrudes from the upper portion of the painting, which seems to be the player’s arm. The arm is bent in such a manner that suggests the player is resting his arm on the arm of a chair and is sitting down. Further suggesting that the player is seated is the round shape to the right of Picasso’s signature in the bottom left portion of the painting. This shape looks as if it could represent the embellishment on the bottom of a chair leg.

The same kind of shape is seen on the right side of the painting and the spacing between the two encourages the viewer to see the shapes as legs to an armchair. A little further up from the second chair leg one can see the beginnings of the accordion. There is one fragment that has three small circles lined up in a vertical row next to what seems to be the last three fingers on a person’s hand. From the title, it can be assumed that this represents someone playing the accordion. Moving left from the hand and keys, there is a series of rectangular shapes, probably meant to depict the folds in an accordion. The keys and folds around the player’s hand are shown from multiple viewpoints, which make it difficult to determine the exact direction of the accordion.

References

- ↑ Voorhies, James (2000). "Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Avgikos, Jan. "Pablo Picasso". Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ Rewald, Sabine. "Cubism". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 8 April 2011.