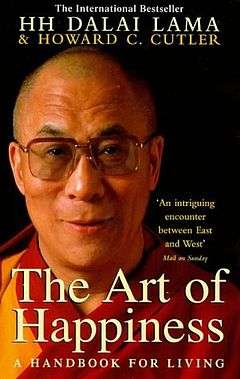

The Art of Happiness

| |

| Author | Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Philosophy |

| Publisher | Easton Press |

Publication date | 1998 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 1-57322-111-2 |

| 294.3/444 21 | |

| LC Class | BQ7935.B774 A78 1998 |

The Art of Happiness (Riverhead, 1998, ISBN 1-57322-111-2) is a book by the Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler, a psychiatrist who posed questions to the Dalai Lama. Cutler quotes the Dalai Lama at length, providing context and describing some details of the settings in which the interviews took place, as well as adding his own reflections on issues raised.[1]

The book explores training the human outlook that alters perception. The concepts that the purpose of life is happiness, that happiness is determined more by the state of one’s mind than by one’s external conditions, circumstances, or events—at least once one’s basic survival needs are met and that happiness can be achieved through the systematic training of our hearts and minds.[2][3]

Chapter summaries

Part I. The Purpose of Life

Chapter 1: The Right to Happiness

"I believe that the very purpose of our life is to seek happiness. That is clear, whether one believes in religion or not, whether one believes in this religion or that religion, we all are seeking something better in life. So, I think, the very motion of our life is towards happiness…” (13). The Dalai Lama spoke this powerful statement at a conference in Arizona among a crowd of people. Chapter one, The Right to Happiness, introduces what the book; the Art of Happiness is about.[4]

Psychiatrist Howard Cutler followed the Dalai Lama around on this tour. Cutler, as well as many of his patients, believed that happiness was “ill defined, elusive, and ungraspable” (14). He also noted that the word ‘happy’ was derived from the term luck or chance (14). His stance on happiness changed after spending some time with this peace leader.[4]

“When I say ‘training the mind,’ in this context I’m not referring to ‘mind’ merely as one’s cognitive ability or intellect. Rather I’m using the term in the sense of the Tibetan word Sem, it includes intellect and feeling, heart and mind. By bringing about a certain inner discipline we can undergo a transformation of our attitude, our entire outlook and approach to living” (15).[4]

The purpose of our life is to seek happiness was the phrase that stuck with him out of every other word the Dalai Lama spoke. After later examining some previous experiments, he came to this conclusion: unhappy people tend to be self-focused, withdrawn, brooding and even antagonistic. “On the other hand, happy people tend to be more sociable, flexible, and creative and are able to tolerate life’s daily frustrations more easily than unhappy people.” (16)

The Dalai Lama sees happiness as an objective: people setting goals and working to achieve them thus creating happiness in oneself.

Chapter 2: The Sources of Happiness

Chapter 1 talks about how to train the mind to become happier; with Chapter 2, we can figure out our sources of happiness or unhappiness. This chapter starts by explaining how a woman being able to retire at age 32 is at a higher level of happiness, but she soon returns to her happiness level before early retirement. Compared to this story, a man is told he’s HIV positive, which brings him to a lower level of happiness, but he soon begins to appreciate every day life more (19–20). These two examples in the book help explain how “happiness is determined more by one’s state of mind than by external events” (20). Being at a life’s high, winning the lottery, or being at a low, diagnosed with cancer, we eventually get back to our baseline level. This baseline level is described in the book as how we react to life-changing news; even then our lives will reach a normal baseline again (21).

Relating to the baseline theory, we have very comparing minds with one another and within ourselves. The book explains how we compare incomes and success, which leads to unhappiness, but we need to flip this state of mind to compare with the less fortunate to appreciate what we have (22–23). According to the Dalai Lama, “If you harbor hateful thoughts or intense anger deep within yourself, then it ruins your health; thus it destroys one of the factors for happiness” (25). We are born into a certain state of mind about happiness, but we can change our outlook by being happier in each moment. For example, we can find more happiness with ourselves through self-worth. Self-worth, according to the Dalai Lama, is having a source of affection, compassion, and a sense of dignity (32). We need a strong sense of contentment to feel happier without obtaining objects, which assists in finding self-worth. Along with material things, we need to be able to decide what is going to bring us happiness or just pleasure. We have to reflect on what will ultimately bring us positive or negative consequences when dealing with a positive or negative action we perform to bring us satisfaction (28). We must ask ourselves if a certain object/action will make us happier or bring us pleasure. 4 4 4

Chapter 3: Training the Mind for Happiness

First step is learning. Analyse thoughts and emotions to determine if they are beneficial or hurtful. Try not to "want." If you know something may tempt you avoid it. Positive desires are good.

Chapter 4: Reclaiming our Innate State of Happiness

The ability to be happy is in everyone’s nature. Happiness is found through love, affection, closeness and compassion. Not only do humans have the capability of being happy, but also the Dalai Lama believes that each human naturally has a gentle quality within them. The Dalai Lama supports this theory by mentioning ‘Buddha nature’, the Buddhist doctrine, but also saying that gentleness is not only affected by religion but in everyday life. With gentleness comes aggression, however. People argue that aggression is the dominant behavior for the human race. In response, the Dalai Lama says, “anger, violence and aggression may certainly arise, but I think it’s on a secondary or more superficial level; in a sense, they arise when we are frustrated in our efforts to achieve love and affection” (54–55). Although aggression can occur, overall our fundamental nature is gentleness. The Dalai Lama believes that because of the advancement in human intelligence we are believed to be capable of controlling our aggression versus our kindness; however, if the intellect level were to decrease then the result would be destructive. So, overall, the Dalai Lama believes that although it is possible to go down the path of aggression there is always the natural ability to be compassionate again. The compassion towards one’s self as humans has to be equally distributed to others. “Reaching out to help others may be as fundamental to our nature as communication” (59). This suggests the idea that humans are “programmed with the capacity and purpose of bringing pleasure and joy to others” (61). Overall, happiness is reached by keeping peace with others and one’s self, which can be reached through meditation and community service. Therefore, the Dalai Lama concludes that the purpose isn’t to create tension but a positive atmosphere. This gives our life meaning, which leads to overall happiness. That positive atmosphere can be found through closeness and compassion.

Part II. Human Warmth and Compassion

Chapter 5: A New Model for Intimacy

Compassion and intimacy are two of the strongest emotions a person can achieve. It is impossible to find these emotions solely within ourselves. We are constantly trying to search for another to be compassionate about, or intimate with. One needs to approach others with a positive attitude, to create an open and friendly atmosphere. Being openly friendly with others, allows one to be compassionate. “We have to maintain an attitude of friendship and warmth in order to lead a way of life in which there is enough interaction with other people to enjoy a happy life” (Dalai Lama, 69).

Intimacy is the central core of our existence. It creates openness with others, which is necessary for a happy lifestyle. According to the Dalai Lama intimacy is “…having one special person with whom you can share your deepest feelings, fears, and so on” (76). The Dalai Lama’s opinion is supported by research of Cutler, as he writes “Medical researchers have found that people who have close friendships, and have people they can turn to for affirmation, empathy, and affection are more likely to survive health challenges such as heart attacks, major surgeries and are less likely to develop diseases and cancer” (78). Intimacy is also physical closeness. “The desire for intimacy is the desire to share ones innermost self with another” (The Dalai Lama, 81). One can express himself too much also. Once a person has opened oneself completely to everyone, the special intimacy is lost, and it is hard to satisfy the need of connection with one special person. “The model intimacy is based on the willingness to open ourselves to many others, to family, friends, and even strangers, forming genuine and deep bonds based on common humanity” (Dalai Lama, 84). By opening oneself to the world around us, it creates the opportunity to form special bonds with someone new, or build upon a relationship one may already have.

Chapter 6: Deepening Our Connection to Others

According to Chapter 5, Howard C. Cutler also asks The Dalai Lama a question about connections and relationships between people: "What would you say is the most effective method or technique of connecting with others in a meaningful way and of reducing conflicts with others?" The Dalai Lama says that there is no formula or exact example for all problems.(87) The Dalai Lama believes that empathy is the key to be more warm and compassionate in connections to others. He thinks that it is very important and extremely helpful to be able to try to put ourselves in the other person's place and see how would we react to the situation.(89) To show compassion and try to understand the background of other people. Cutler also writes a few stories/experiences from his life. For instance when he was in an argument with someone and his reaction was inappropriate without trying to understand and appreciate what the other person might think – no empathy.

The Dalai Lama does not just refer to caring for each other; he also finds relationships very important and differentiates them in two ways.(111) The first is when you are in a relationship with someone because of wealth, power or position (material) – when these things disappear, the relationship normally ends. The second way is based on true human feelings (spiritual). The Dalai Lama also informs about sexual relationships. You can have a sexual relationship with no respect for each other. Usually it is just temporary satisfaction. Or sexual relationships bonded with a person who we think is kind, nice and gentle.(101–102)

After discussing relationships and sexual relationships in general, The Dalai Lama continues to speak about love. He does not believe in true love – in falling in love. His opinion on this subject is very negative; he describes idealized romantic love as a fantasy and that it is unattainable – just simply not worth it. (111) But he also says that closeness and intimacy are some of the most important components of human happiness.(112)

According to Chapter 6 we can say that the Dalai Lama clearly represents his opinions on human relationships, empathy and sexual attraction, and he tries to explain them in a simple way. These are the most important and most discussed topics in Chapter 6. We find out how empathy is needed in human relationships. That understanding and trying to appreciate the other person's emotional background is priceless. Also that relationships are either materially or spiritually based. On the other hand, the Dalai Lama does not believe in love and describes it as a fantasy or imagination, although he thinks that true relationships are based on true human feelings. All these new information are related to Chapter 7's main topic which is basically about the value and benefits of compassion.

Chapter 7: The Value and Benefits of Compassion

This chapter is composed of defining compassion and the value of human life. The Dalai Lama defines compassion as a “state of mind that is nonviolent, nonharming, and nonaggressive” (114). This feeling of compassion is broken down into two types. First is compassion associated with attachment. Using this type of compassion alone is biased and unstable, which causes certain emotional attachments that are not necessarily good. The second type is genuine compassion that “is based on others' fundamental rights rather than your own mental projection” (115). This type of compassion is also defined “as the feeling of unbearableness” (116). Accepting another's suffering brings that person a sense of connectedness and gives us a willingness to reach out for others. Associating oneself with this type of fundamental rights generates love and compassion. According to the Dalai Lama the reason he separated compassion into two types was because “the feeling of genuine compassion is much stronger, much wider [and] has a profound quality” (116). Using genuine compassion creates a special connection that you cannot achieve with associating compassion with attachments.

The Dalai Lama believes that compassion “provides the basis of human survival” (119). People reflect off their own experiences and this contributes to their knowledge of compassion. If people feel there is no need to develop compassion then it's because they are being blocked by "ignorance and shortsightedness" (121). This can be caused by not seeing the physical and emotional benefits of having a compassionate mindset. When one completely understands the importance of compassion, then it "gives you a feeling of conviction and determination" (125). Having this determination can bring one to have a compassionate mindset.

There have been numerous studies that support the idea that “developing compassion and altruism has a positive impact on our physical and emotional health” (126). James House found that “interacting with others in warm and compassionate ways, dramatically increased life expectancy, and probably overall vitality as well” (126). These studies have concluded that there is a direct correlation to compassion and physical and emotional health. The next chapter tells how to cope with suffering, from the loss of a loved one.

Part III. Transforming Suffering

Chapter 8: Facing Suffering

Throughout this chapter the Dalai Lama gives examples of how different people dealt with losing a loved one. The Dalai Lama states that he believes it is a good idea to prepare yourself ahead of time for the kinds of suffering you might encounter, because sometime in life you are going to experience some type of suffering, so if you prepare yourself you will know what to expect. He goes on about how everyone is going to face suffering sometime in their life and if we view suffering as something natural then we can begin to live a happier life. If you can prepare yourself for the fact that in your life you're going to experience a traumatic event, for example a death of a family member, you can face the fact that everybody in life eventually passes on and you’ll be able to get over the grieving process sooner and carry on with a happier life knowing that they're in a better place. The Buddhist recognizes the possibility of clearing the mind and achieving a state in which there is no more suffering in people’s lives. If you come to the fact and realize you are suffering you’ll overcome it faster rather than denying that everything is all right.

Getting through suffering is a very difficult thing to accomplish but there are people out there who can help you overcome you losing a loved one or whatever you may be suffering from. Everyone has to go through suffering sometime in their life, but how people get over it shows how strong that person is. How someone perceives life as a whole plays a huge role in a person’s attitude about pain and suffering. There is a possibility of freedom from suffering. That is possible by removing the causes of suffering and living a happier life.

Chapter 10: Shifting Perspective

The chapter starts right off with lots of quotes from the Dalai Lama. He talks about how you can always change your perspective of something if you just step back and change your view. Also in this chapter he goes on to talk about your enemies in life. The Dalai Lama talks about how having enemies in life in the end helps you out, you just have to change your view or perspective. The author also goes on to talk about how all this stuff is still practical in today’s world. In this chapter the Dalai Lama keeps stressing the importance of practicing patience. One big part of this chapter was the talk about finding balance. The Dalai Lama goes on to talk about how living well has to do with a big part of having balance in your life. He also talks about how you need both physical and emotional balance in your life. He also goes on to say that one should not go to extremes with anything; if you have a balanced life you will not go to extremes with anything. He thinks that narrow-minded people are the ones who go to extremes and this results in trouble and danger.

Chapter 11: Finding Meaning in Pain and Suffering

While chapter ten talks about shifting your perspective, chapter 11 talks about finding the meaning in pain and suffering, turning them into something you can reflect upon yourself. Victor Frankl was a Jewish psychiatrist and was imprisoned by the Nazis. He had a brutal experience in a concentration camp and gained insight into how people survived the atrocities (199). He observed that those who survived did so not because of youth or physical strength, but the strength derived from purpose. Being able to find meaning in suffering is powerful because it helps us cope even during the most difficult times in our lives. Being able to feel the rewards, we must search for meaning when things are going well for us too (200). For many people the search starts with religion. They give some examples from Buddhist and Hindu models. For our faith and trust in His plan allows us to tolerate our suffering more easily and trusting His plan he has for us. They give an example on how pain can be a good thing such as childbirth. It is very painful to give birth but the reward is having the child. Having suffering can strengthen us in many ways because it can test and strengthen our faith, it can bring us closer to God in a very fundamental and intimate way, or it can loosen the bonds to the material world and make us clever to God as our refuge (201). Clever to God means being or feeling closer to him and knowing what you should do.

They talk about the Mahayana visualization practice, it's where you mentally visualize taking on another person's pain and suffering and in return you give them all of your resources, good health, fortune and so on (203). When doing this you reflect on yourself and look at your situation and then look at the others and see if their situation is worse and if so you tell yourself that you could have it as bad as them or worse. By realizing your suffering you will develop greater resolve to put an end to the causes of suffering and the unwholesome deeds that lead to suffering. It will increase your enthusiasm for engaging in the wholesome actions and deeds that lead to happiness and joy. When you are aware of your pain and suffering it helps you to develop your amount of empathy. Allow you to relate to other people's feelings and suffering. Our attitude may begin to change because our sufferings may not be as worthless and as bad as we may think. Dr. Paul Brand went to India and explored over there and looked at how people suffered physical pain. He says it is a good thing we have physical pain because if we didn’t then how would we know that something is wrong with our bodies? (207) If we did not feel pain we would harm our bodies because we could stick our hands into fire. Not every practice may work for everyone. Everyone just has to try and figure out their own way of dealing with suffering and turning it into a positive feedback.

Part V. Closing Reflections on Living a Spiritual Life

Chapter 15: Basic Spiritual Values

The beginning of the chapter discusses how the art of happiness has many different components. It talks about what the book has established so far about happiness—how we need to understand the truest sources of happiness and set our priorities in life based on the cultivation of those sources. Then it introduces us to the final chapter about spirituality.

The author goes on to talk about how when people hear the word "spirituality" they automatically think it goes with religion. He says that despite the Dalai Lama having a shaved head and wearing robes, they had normal conversations like two normal people.

The Dalai Lama says that having a process of mental development is key. We need to appreciate our potential as human beings and recognize the importance of our inner transformation. He talks about how there are two different levels of spirituality (295). One level is to do with religious beliefs; he says that he thinks each individual should take their own spiritual path that best fits them and their mental disposition, natural inclination, temperament, and cultural background (305).

Lama says that all religions can make an effective contribution for the benefit of humanity; they are designed to make the individual a happier person and the world a better place and we should respect them (305).

At the end of the chapter he talks about how deep religious faith has sustained countless people through difficult times. He tells a story about a man named Terry Anderson who was kidnapped off the streets in Beirut in 1985. After seven years of being held as a prisoner by Hezbollah, a group of Islamic fundamentalist extremists, he was finally released. The world found him a man overjoyed and happy to be reunited with his family and he said that prayers and religion got him through those seven years (303). This is the main example Lama used.

Other editions

Easton Press recently published a leather-bound edition.

Other books by the Dalai Lama

- A sequel, The Art of Happiness at Work, was published in 2003 by Riverhead Press (ISBN 1-57322-261-5), also with Howard Cutler.

- Ethics for the New Millennium (1999). Riverhead Press. (ISBN 1-57322-025-6).

- An Open Heart, edited by Nicholas Vreeland. Back Bay Books. (ISBN 0-316-98979-7).

For other books, see Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama: Other writings

References

- ↑ The Art of Happiness:. Google. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Art of Happiness - Dalai Lama, Howard Cutler". Ciao Uk. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Art of Happiness by the Dalai Lama". Abode of eBooks. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 "The Art of Happiness, 10th Anniversary Edition: A...". Shara Books. Retrieved 18 July 2013.