The Black Crook

| The Black Crook | |

|---|---|

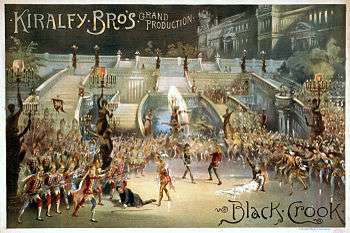

|

Finale of The Black Crook | |

| Music |

Thomas Baker Giuseppe Operti George Bickwell |

| Lyrics | Theodore Kennick |

| Book | Charles M. Barras |

| Productions |

1866 Broadway 1870 Broadway revival 1872 Broadway revival |

The Black Crook is often considered to be the first piece of musical theatre that conforms to the modern notion of a "book musical".[1] The book is by Charles M. Barras (1826–1873), an American playwright. The music is mostly adaptations, but some new songs were composed for the piece, notably "March of the Amazons" by Giuseppe Operti, and "You Naughty, Naughty Men", with music by George Bickwell and lyrics by Theodore Kennick.

It opened on September 12, 1866 at the 3,200-seat Niblo's Garden on Broadway, New York City and ran for a record-breaking 474 performances. It was then toured extensively for decades and revived on Broadway in 1870–71, 1871–72 and many more times after that. This production gave America claim to having originated the musical. The Black Crook is considered a prototype of the modern musical in that its popular songs and dances are interspersed throughout a unifying play and performed by the actors.[2]

The British production of The Black Crook, which opened at the Alhambra Theatre on December 23, 1872, was an opera bouffe version based on the same French source material, with new music by Frederic Clay and Georges Jacobi. The musical was also produced in 1882 in Birmingham, Alabama. A silent film version of The Black Crook was produced in 1916.[3] It is the only screen version of the show.

Background

The Black Crook was born in 1866 when a dramatic group and Parisian ballet troupe joined forces in New York. Henry C. Jarrett and Harry Palmer had hired the ballet troupe to perform at the New York Academy of Music but the troupe was left without an engagement when a fire destroyed the Academy. They approached William Wheatley, the manager at Niblo's Garden, to see if he could use them. Wheatley offered them a chance to participate in a Faustian musical "spectacle" by combining their ballet forces (and the spectacular stage machinery they had brought over from Europe) with Charles M. Barras's melodrama.[1][4]

In operas, even comic operas with dialogue like The Magic Flute, the principal singers leave the dancing to the ballet troupe. In burlesque, music hall and vaudeville, there is little or no unifying story, just a series of sketches. So The Black Crook, with song and dance for everyone, was an evolutionary step, and has been called the first musical comedy.[2][5][6] Cecil Michener Smith dissented from this view, arguing that "calling The Black Crook the first example of the theatrical genus we now call musical comedy is not only incorrect; it fails to suggest any useful assessment of the place of Jarrett and Palmer's extravaganza in the history of the popular musical theatre ... but in its first form it contained almost none of the vernacular attributes of book, lyrics, music, and dancing which distinguish musical comedy."[7] Another dissenter is Larry Stempel.[8]

The same year that The Black Crook opened, The Black Domino/Between You, Me and the Post was the first show to call itself a "musical comedy".[2] In the late 1860s, as post-Civil War business boomed, there was a sharp increase in the number of working- and middle-class people in New York, and these more affluent people sought entertainment. Theaters became more popular, and Niblo's Garden, which had formerly hosted opera, began to offer light comedy. The Black Crook was followed by The White Fawn (1868), Le Barbe Blue (1868) and Evangeline (1873).[9] An apparently similar show from six years earlier, The Seven Sisters (1860), which also ran for a very long run of 253 performances, is now lost and forgotten. It also included special effects and scene changes. Theatre historian John Kenrick suggests that The Black Crook's greater success resulted from changes brought about by the Civil War: First, respectable women, having had to work during the war, no longer felt tied to their homes and could attend the theatre, although many did so heavily veiled. This substantially increased the potential audience for popular entertainment. Second, America's railroad system had improved during the war, making it feasible for large productions to tour.[9]

Productions

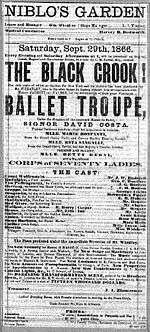

The original production opened on September 12, 1866 at the 3,200-seat Niblo's Garden on Broadway. It was a staggering five-and-a-half hours long, but despite its length, it ran for a record-breaking 474 performances, and revenues exceeded a record-shattering one million dollars. It was produced by the theatre's manager, Wheatley, who also directed the piece.[2]

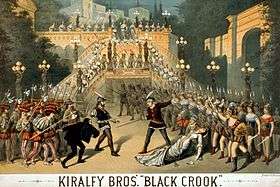

The production included state-of-the-art special effects, including a transformation scene that converted a rocky grotto into a fairyland throne room in full view of the audience. The cast included Annie Kemp Bowler, Charles Morton, John W. Blaisdell, E.B. Holmes, Millie Cavendish and George C. Boniface.[10] The poster announced with great emphasis the presence of a "Ballet Troupe of Seventy Ladies" choreographed by David Costa. This scantily-clad female dancing chorus in skin-colored tights was a big draw. It was respectable enough for the middle-class audience, but very daring and controversial enough to attract a great deal of press attention. The dance soloists were two Italian ballerinas from the school of Teatro alla Scala of Milan, Marie Bonfanti and Rita Sangalli, who went on to star in further New York productions.[11] The musical was then toured extensively for decades and revived on Broadway in 1870–71, 1871–72, and by The Kiralfy Brothers at Niblo's in 1873; and many more times after that.[2]

The British production of The Black Crook, which opened at the Alhambra Theatre on December 23, 1872, was an opera bouffe version based on the same French source material, with new music by Frederic Clay and Georges Jacobi. The author, Harry Paulton, starred as Dandelion, opposite the comedian Kate Santley, who had appeared in the 1871–72 Broadway revival. The Black Crook was also produced in 1882 in Birmingham, Alabama as the opening-night attraction at O'Brien's Opera House.[12]

Synopsis

The musical is set in 1600 in the Harz Mountains of Germany. It incorporates elements from Goethe's Faust, Weber's Der Freischütz, and other well-known works.

Evil, wealthy Count Wolfenstein seeks to marry the lovely village girl, Amina. With the help of Amina's scheming foster mother Barbara, the Count arranges for Amina's fiancé, Rodolphe, an impoverished artist, to fall into the hands of Hertzog, an ancient, crook-backed master of black magic (the Black Crook). Hertzog has made a pact with the Devil (Zamiel, "The Arch Fiend"): he can live forever if he provides Zamiel with a fresh soul every New Year's Eve. As innocent Rodolphe is led to this horrible fate, he discovers a buried treasure and saves the life of a dove. The dove magically transforms into human form as Stalacta, Fairy Queen of the Golden Realm. She rewards Rodolphe for rescuing her by bringing him to fairyland and then reuniting him with his beloved Amina. Her army defeats the Count and his evil forces, demons drag Hertzog into hell, and Amina and Rodolphe live happily ever after.

Musical numbers

|

|

Principal roles

- Count Wolfenstein – John W. Blaisdell

- Rodolphe (a poor artist) – George C. Boniface

- Von Puffengruntz (the Count's corpulent steward) – J. G. Burnett

- Hertzog, surnamed the Black Crook (a hideously deformed alchymist and sorcerer) – C. H. Morton

- Greppo (his drudge) – George Atkins

- Wulfgar (a gypsy ruffian) – E. Barry

- Jan – Frank Little

- Bruno (his companion) – F. Ellis

- Casper (a peasant) – H. Weaver

- Amina (bethrothed to Rodolphe) – Rose Morton

- Dame Barbara (her foster-mother) – Mary Wells

- Carline – Millie Cavendish

- Rosetta (a peasant) – C. Whitlock

- Stalacta (Queen of the Golden Realm) – Annie Kemp Bowler

- Zamiel (the Arch-Fiend) – E. B. Holmes

- Skuldawelp (Familiar to Hertzog) – Mr. Rendle

- Redglare (the Recording Demon) – F. Clark

- Villagers, Peasants, Choresters, Guards, Attendants, Fairies, Sprites, Naiads, Submarine Monsters, Gnomes, Skeletons, Apparitions, Demons, Monsters, etc.

Critical reception

The overlong piece survived a rocky opening night, and numerous cuts were subsequently made.[1] According to Doug Reside, a curator at New York Public Library for the Performing Arts:

The New York Herald published an op-ed piece "condemning" the play for the indecency of the costumes and dancing, suggesting that there may have been "in Sodom and Gomorrah ... such a theatre and spectacle on the Broadway of those doomed cities," and urging those "determined to gaze on the indecent and dazzling brilliancy of the Black Crook" to "provide themselves with a piece of smoked glass." However, Joseph Whitton, William Wheatley's business manager, explains in his short history of the play, the editor of The New York Herald was likely aware that such condemnation would promote the show and was rewarding Wheatley for his loyalty to the paper. The moral crusade against the show was taken up by Reverend Charles Smyth who preached a fire and brimstone sermon against it as part of a public lecture series. All of this, of course, simply increased public interest.[1]

Robert C. Allen wrote in his 2000 book, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture, that if Whitton is correct, it was the first such "covert advertising ploy on behalf of the theatre management".[13]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Reside, Doug. "Musical of the Month: The Black Crook", New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, June 2, 2011, accessed July 2, 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 Morley, p. 15

- ↑ "The Black Crook". 10 January 1916 – via IMDb.

- ↑ Article on the creation of The Black Crook

- ↑ "Broadway's first musical: The Black Crook". The Bowery Boys, November 26, 2007, accessed 1 March 2010; the Encyclopædia Britannica entry on the musical agrees (subscription required)

- ↑ Grosch, Nils and Tobias Widmaier (Hrsg.) (2010) Lied und populäre Kultur – Song and Popular Culture

- ↑ Smith, Cecil. Musical Comedy in America, New York, The Colonial Press, 1950

- ↑ Stempel, Larry. Showtime: A History of the Broadway Musical Theatre, p. 49: "[T]he claim would be hard to sustain on purely historical grounds whatever criteria one chooses to apply."

- 1 2 Kenrick, John. "Stage 1860s: The Black Crook". Musicals101.

- ↑ The Black Crook, Musical Heaven

- ↑ "Revival of the Ballet", The New York Times, September 1, 1901, p. SM3

- ↑ Baggett, James (November 2007) "Timepiece". Birmingham magazine, vol. 47, No. 11, pp. 266-67

- ↑ Allen, Robert C. Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture, University of North Carolina Press (2000), p. 113 ISBN 0807860085

References

- Morley, Sheridan. Spread A Little Happiness, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987

- Barras, C. M. (1866). The Black Crook a most wonderful history. Philadelphia: Barclay.text available here.

- New Complete Book of the American Musical Theatre by David Ewen, 1970

- Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography edited by James Grant Wilson, John Fiske and Stanley L. Klos, 1999

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Black Crook. |

- New York Public Library

- Photos of The Black Crook from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection

- Audio files to several songs from The Black Crook, from the Library for the Performing Arts "Musical of the Month" series

- Sheet Music from the Library for the Performing Arts "Musical of the Month" series

- Additional sites

- The Black Crook Digital Collection from the Harry Ransom Center includes books, sheet music, photographs, prints, playbills and newspaper clippings.[1]

- Information about NY and London productions

- Cover art for the 1867 Transformation Polka musical arrangement

- Complete text of the libretto

- Full-color digital images of annotated 19th century promptbook for the Black Crook

- ↑ "New digital collection of The Black Crook musical released". Cultural Compass. Retrieved 2016-09-10.