The Dybbuk

| The Dybbuk | |

|---|---|

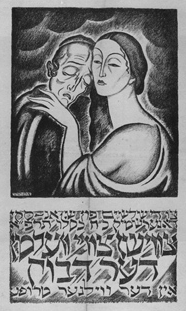

Hanna Rovina as Leah in the Hebrew-language premiere of The Dybbuk. Habima Theater, Moscow, 31 January 1922. | |

| Written by | S. Ansky |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | December 9, 1920 |

| Place premiered | Elizeum Theater, Warsaw |

| Original language | Russian |

| Genre | Drama |

| Setting | Brinitz and Miropol, Volhynia, Pale of Settlement |

The Dybbuk, or Between Two Worlds (Russian: Меж двух миров [Дибук], trans. Mezh dvukh Mirov [Dibuk]; Yiddish: - דֶער דִבּוּק צִווִישֶן צְווַיי ווֶעלְטֶן , Tzvishn Zwey Weltn – der Dibuk) is a play by S. Ansky, authored between 1913 and 1916. It was originally written in Russian and later translated into Yiddish by Ansky himself. The Dybbuk had its world premiere in that language, performed by the Vilna Troupe at Warsaw in 1920. A Hebrew version was prepared by Hayim Nahman Bialik, and staged at Habima Theater, Moscow in 1922.

The play, which depicts the possession of a young woman by the malicious spirit – known as Dybbuk in Jewish folklore – of her dead beloved, became a canonical work of both Hebrew and Yiddish theatre, being further translated and performed around the world.

Characters

- Leah, daughter of Sender, a maiden who had come of age and yet her father constantly rejects her suitors

- Khanan, a poor Yeshiva student enamored with Leah, who is rumored to practice forbidden Kabbalah

- Sender, son of Henya, a rich merchant who resides in Brinitz, Leah's father.

- The Messenger, a sinister, unnamed traveler.

- Rabbi Azriel, son of Hadasa, A venerable hasidic Tzadik who resides in nearby Miropol, reputed to be a miracle-worker

- Nisan, son of Karina, a scholar who knew Azriel

- Rabbi Samson, Mara d'atra (chief rabbi) of Miropol.

- Michael, Azriel's servant

- Meyer, beadle in the Brinitz synagogue

- Gittel and Besya, Leah's friends

- Frieda, her old nurse

- Menashe, Leah's new betrothed

- Nakhman, his father

- Asher and Hanoch, Yeshiva students and friends of Khanan

- The two Dayannim, the religious judges presiding alongside Samson

- Three idlers, who waste their time in the study hall

- Azriel's hasidim, poor folk, crowd

Plot summary

Act I

The play is set in the Jewish town (Shtetl) of Brinitz, presumably near Miropol, Volhynia, in the Pale of Settlement. No date is mentioned, but it takes place after the death of David of Talne, who is said to be "of blessed memory", in 1882.

Three idlers lounge in the synagogue, telling stories of the famed hasidic Tzadikim and their mastery of Kabbalah powers. They are accompanied by the Messenger, a sinister stranger who demonstrates uncanny knowledge of the subject. Khanan, a dreamy, emaciated student, joins them. Upon seeing him, the three gossip of his reputed dealing with the secret lore. They discuss Leah, the daughter of rich Sender, whose suitors are constantly faced with new demands from her father until they despair. Khanan, who is obviously in love with her, rejoices when one of the idlers tells another proposed match came to nothing. Then Sender himself enters, announcing that he wavered but eventually closed the deal. The townspeople flock to congratulate him. Khanan is shocked, mumbling all his labors were in vain, but then something dawns on him and he is ecstatic. He falls to the floor. The townspeople are busy with Sender, but eventually notice Khanan and try to awake him. They discover he is dead, and that he clasped the Book of Raziel.

Act II

Several months later, Leah's wedding day has arrived. As decreed by custom, a humble feast is held for the poor folk prior to the ceremony, and the maiden dances with the beggars. She and her nurse discuss the fate of the souls of those who died prematurely, mentioning Khanan whom Leah says came to her in a dream. They visit the holy grave in the center of Brinitz, the resting place of a bride and a groom who were killed under their wedding canopy when the "Evil Chmiel" raided the area in 1648. She ceremoniously invites the souls of her mother and grandparents to her celebration. Menashe, her betrothed, arrives with his father. At the ceremony, he approaches to remove Leah's veil. She shoves him back, screaming in a man's voice. The Messenger, standing nearby, announces she is possessed by a Dybbuk.

Act III

In the home of the Tzadik Azriel of Miropol, the servant enters to announce that Sender's possessed daughter has arrived. Azriel confides to his assistant that he is old and weak, but the latter encourages him with tales of his father and grandfather, both renowned miracle-workers. He calls Leah and demands from the spirit to leave her body. The Dybbuk refuses. Azriel recognizes him as Khanan, and summons the rabbincal court to place an anathema upon him. Rabbi Samson arrives and tells the spirit of Nisan, a scholar who died and knew the Tzadik, came to him in a dream. He told that Khanan is his son and he sues Sender before the court, on the charge he is responsible for his death. The rabbis determine to hold the litigation on the day after, and exorcise the spirit only upon discovering the truth.

Act IV

Nisan's soul arrives at the court and communicates via Rabbi Samson. He tells the assembled that he and Sender were old friends, and swore that if one would father a son and the other a daughter, they will be married to each other. Nisan died prematurely, but his son Khanan arrived at Brinitz and his heart went after Leah, as was destined. He claims that Sender recognized him but did not want to have his daughter marry a poor man. Sender confides that he felt a strange urge to reject all suitors and take Khanan, but he eventually managed to resist it. Nisan pleads on, stating his desperate son turned to the Other Side and died, leaving him with none to say Kaddish after him.

The court absolves Sender, stating that one cannot promise an object not yet created under the laws of the Torah, but fine him severely and oblige him to say Kaddish for Nisan and Khanan for all his life. Azriel commands the spirit to exit Leah's body, but it refuses. The holy man than conducts a dramatic exorcism, summoning various mystical entities and using ram horns' blasts and black candles. The Dybbuk is forced out. Menashe is invited, and a wedding is prepared. When Leah lies alone, she senses Khanan's spirit and confides she loved him ever since seeing him for the first time. Mourning her never-to-be children, she rises and walks towards him. The two are united in death.

Writing

Between 1912 and 1913, S. Ansky headed an ethnographic commission, financed by Baron Vladimir Günzburg and named in honor his father Horace Günzburg, which traveled through Podolia and Volhynia in the Pale of Settlement. They documented the oral traditions and customs of the native Jews, whose culture was slowly disintegrating under the pressure of modernity. According to his assistant Samuel Schreier-Shrira, Ansky was particularly impressed by the stories he heard in Miropol of a local sage, the hasidic rebbe Samuel of Kaminka-Miropol (1778 – May 10, 1843), who was reputed to have been a master exorcist of dybbuk spirits. Samuel served as the prototype for the character Azriel, who is also said to reside in that town.[1] Historian Nathaniel Deutsch suggested he also drew inspiration from the Maiden of Ludmir, who was also rumored to have been possessed, thus explaining her perceived inappropriate manly behavior.[2]

Craig Stephen Cravens deduced that Ansky began writing the play in late 1913. It was first mentioned in a reply to him from Baron Günzburg, on 12 February 1914, who commented he read a draft and found it compelling. The original was in Russian; shortly after completing it, the author was advised by friends to translate it into Yiddish. In the summer, he started promoting The Dybbuk, hoping it would be staged by a major Russian theater. He was rebuffed by Semyon Vengerov of the Alexandrinsky Theatre, who explained they could not perform another play by a Jew after the negative reaction to Semyon Yushkevich's Mendel Spivak. Ansky then contacted the managers of the Moscow Art Theatre. He failed to secure a meeting with Constantin Stanislavski himself, but director Leopold Sulerzhitsky read the play during the autumn, and replied much further work was required. Guided by him via correspondence, the author rewrote his piece through 1915. When he accepted the revised version in September, Sulerzhitsky regarded it as much better, but not satisfactory. At that time, Ansky's publisher Zinovy Grzhebin submitted it to the state censorship in St. Petersburg. Censor Nikolai von Osten-Driesen commented the banishment of the spirit resembled the Exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac, and Ansky rewrote the scene using subtler terms. This version was approved by Driesen on 10 October, after removing another minor reference to angels. The play was still undergoing modifications: on 21 October, Ansky propositioned to Sulerzhitsky they add a prologue, epilogue and a long scene of Leah's wedding day. He agreed, and the censor approved the expanded edition on 30 November. Both copies submitted by Ansky were found in 2001 at the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts. They were considerably different from the known stage version: most notably, the Messenger was not yet conceived.

Stanislavski agreed to review the play, though not thoroughly, on 30 December. Though many accounts link him with The Dybbuk, Cravens commented this is the only actual documentation in the matter. He never even watched The Dybbuk fully. He and the rest of the management continued to request revisions. On 25 November 1916, Ansky wrote in his diary that Stanislavski was almost pleased, asking but for only minor changes in the ending. On 8 January 1917, the press reported the Moscow Art Theatre accepted The Dybbuk and was preparing to stage it.

At the very same time, Stanislavski was supporting the incipient Habima Theater, a Hebrew-language venture headed by Nachum Tzemach. Ansky read his play to Hillel Zlatopolsky, a patron of Habima, who purchased the rights to translate it to Hebrew. The author set but one condition, demanding it would be handed over to Hayim Nahman Bialik. The latter accepted the task in February and completed it in July. Bialik's translation was the first version of the play to be published: it was released in the Hebrew literary magazine Ha'tkufa in February 1918. Meanwhile, the Moscow Art Theatre's planned production of The Dybbuk encountered severe hardships. Michael Chekhov, cast as Azriel, had a severe nervous breakdown due to the use of extreme acting techniques; Stanislavski fell ill with typhus. On 7 March 1918, Boris Suskevich notified Ansky his play was not to be include in that season's repertoire. The author left the city to Vilnius, losing his original copy on the way, but eventually receiving another from Shmuel Niger. He read his renewed edition before David Herman, director of the Vilna Troupe, but did not live to see it performed. He died on November 8, 1920.[3]

Stage productions

On 9 December, at the end of the thirty days' mourning after Ansky's departure, Herman and his troupe staged the world premiere of The Dybbuk in Yiddish, at the Warsaw Elizeum Theater. Miriam Orelska, Alexander Stein, Abraham Morevsky and Noah Nachbusch portrayed Leah, Khanan, Azriel and the Messenger, respectively. The play turned into a massive success, drawing large audiences for over a year, from all the shades of society and a considerable number of Christians. A Yiddish columnist in Warsaw remarked that "of every five Jews in the city, a dozen watched The Dybbuk. How could this be? It is not a play you attend merely once." In the Polish capital alone, they staged it over three hundred times. During their tour across Europe between 1922 and 1927, it remained the pinnacle of their repertoire. While most of their acts drew few visitors, The Dybbuk remained an audience magnet.

On 1 September 1921, the play had its American premiere in the New York Yiddish Art Theatre of Maurice Schwartz. Celia Adler, Bar Galilee, Schwartz and Julius Adler appeared as Leah, Khanan, Azriel and the Messenger. It ran for several months.

While Habima Theater accepted Bialik's translation much earlier, both the intricacy of the play and the production of others delayed its stagings. Director Yevgeny Vakhtangov planned it for years. He originally cast Shoshana Avivit (Lichtenstein), one of his young actresses, as Leah. Avivit was a notorious prima donna and an intimate friend of Bialik, and abandoned the theater unexpectedly on 21 March 1921, due to constant quarrels with the directors. She was confident that the management would call her back, but they dismissed her of the role of Leah, to Bialik's chagrin; he ceased attending rehearsals. Vakhtangov gave the piece to Hanna Rovina, to the dismay of his associates, who considered the thirty-year-old actress too mature for portraying an eighteen-year-old Leah. Rovina was recovering from Tuberculosis in a sanatorium north of Moscow, and left the establishment in spite of the doctors' protests. Leah became her signature role.[4] The Hebrew-language premiere was staged on 9 December 1920, at Habima's residence in the Sekretariova Theater. Rovina, the female Miriam Elias (who was replaced by male actors in subsequent stagings), Shabtai Prudkin and Nachum Tzemach appeared in the four leading roles. Habima performed it precisely 300 times in the Soviet Union, 292 in Moscow; the last was on 18 January 1926, before it embarked on an international tour.

In the British Mandate of Palestine, it premiered in a makeshift production organized by a labor battalion paving Highway 75; while the exact date was unrecorded, it was sometime in February 1922. Abba Hushi depicted Azriel. Professional stagings soon followed suit. On the 6th and 16 June 1926, in two consecutive meetings, the members of the Hebrew Writers Union in Tel Aviv conducted "the Dybbuk trial", a public debate attended by an audience of 5,000 people. They discussed the gap between the needs of the Zionist enterprise and the play's atmosphere, voicing concern that it might overshadow the "young Hebrew culture" developing in Palestine, struggling to free itself from the constraints of diaspora mentality. Eventually, they approved the play.

The German-language premiere opened on 28 February 1925, in Vienna's Rolandbühne, with Friedrich Feher as Azriel and Magda Sonja playing Leah. The first English production ran from 15 December 1925 and 1926 at the off-Broadway Neighborhood Playhouse in New York City. It was translated and adapted by Henry G. Alsberg. On 31 January 1928, Gaston Baty's French-language version premiered in the Studio des Champs-Élysées.

In 1977, Joseph Chaikin, a central figure in American avant-garde theatre, directed a new translation of The Dybbuk by Mira Rafalowicz, a dramaturg, yiddishist and longtime collaborator of Chaikin's at The Public Theater. The Royal Shakespeare Company staged Rafalowicz' translation, directed by Katie Mitchell, in 1992. A two-person adaptation by Bruce Myers, won him an Obie when he performed it at New York in 1979.[5] (The Jewish Theatre San Francisco, formerly Traveling Jewish Theatre) and won several awards. A new adaptation by Canadian playwright Anton Piatigorsky opens at Toronto's Soulpepper Theatre in May 2015.

Adaptations

Besides stories, Ansky also collected traditional melodies, one of which he incorporated into this play. When Aaron Copland attended a performance of the play in New York in 1929, he was struck by this melody and made it the basis of his piano trio Vitebsk, named for the town where Ansky was born.[6]

In 1929 George Gershwin accepted a commission from the Metropolitan Opera to write an opera based on "The Dybbuk." When he was unable to acquire the rights, he instead began work on his opera "Porgy and Bess".[7]

The play has been adapted into the 1937 film The Dybbuk, directed by Michał Waszyński. David Tamkin and Alex Tamkin adapted the play into the opera The Dybbuk, which was composed in 1933 but did not premiere until 1951. Lodovico Rocca also adapted the play into an opera, Il Dibuk.

Sidney Lumet directed a segment for "Play of the Week" based on the play, but adapted into English by Joseph Liss. The program was aired on October 3, 1960.[8] Based on the play, Leonard Bernstein composed music for the 1974 ballet Dybbuk by Jerome Robbins.

It was adapted for CBS Radio Mystery Theater in 1974 under the title The Demon Spirit.[9] Another version was made for BBC Radio 4 in 1979 starring Cyril Shaps, but is believed lost.[10]

The American composer Solomon Epstein composed The Dybbuk: An opera in Yiddish. The opera was premiered in Tel-Aviv, 1999, and this is apparently the world’s first original Yiddish opera. Ofer Ben-Amots composed The Dybbuk: Between Two Worlds, an opera based on the play which premiered in January 2008 in Montreal, Canada.[11]

References

- ↑ Nathaniel Deutsch, The Jewish Dark Continent, Harvard University Press, 2009. p. 47-48.

- ↑ Nathaniel Deutsch, The Maiden of Ludmir: A Jewish Holy Woman and Her World, University of California Press, 2003. p. 9, 15-16.

- ↑ Gabriella Safran, Steven Zipperstein (editors), The Worlds of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Intellectual at the Turn of the Century. Stanford University Press, 2006. pp. 362-403.

- ↑ Carmit Gai, ha-Malkah nasʻah be-oṭobus : Rovina ṿe-"Habimah", Am Oved, 1995. ISBN 9651310537. p. 72-73.

- ↑ tjt-sf.org

- ↑ Aaron Copland and Vivian Perlis, Copland 1900 through 1942. ISBN 978-0-312-01149-9

- ↑ Howard Pollack. "George Gershwin: His Life and Work". University of California Press, 2007, p. 568.

- ↑ Hoberman, J. The Dybbuk. Port Washington, NY: Entertainment One U.S. LP, 2011.

- ↑ "H258: The Demon Spirit by CBS Radio Mystery Theater – Relic Radio". Relicradio.com. 1974-10-23. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ "DIVERSITY - radio drama - Afternoon Theatre,lost plays". Suttonelms.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ "The classic tale of love and mystical possession, in a new adaptation". The Dybbuk. 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Dybbuk. |

- Jewish Heritage Online article on The Dybbuk

- The Dybbuk at the Internet Broadway Database

- Love and Desire “Between Two Deaths”: Žižek avec An-sky

- The Dybbuk Arrives in New York: Maurice Schwartz's Dybbuk Production at the Yiddish Art Theater in 1921

- The Dybbuk Comes to Broadway: Nahum Zemach's Dybbuk Production at the Mansfield Theatre

- The Habima Theatre’s Paris Tour, summer of 1926

- The Dybbuk Dances