The Golden Cockerel

| The Golden Cockerel | |

|---|---|

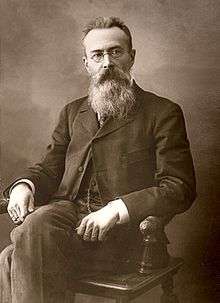

| Opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | |

Ivan Bilibin's 1909 stage set design for Act 2: The Tsardom of Tsar Dadon, Town Square | |

| Native title | Zolotoy petushok (Золотой петушок) |

| Other title | Le coq d'or |

| Librettist | Vladimir Belsky |

| Language |

|

| Based on | Pushkin's "The Tale of the Golden Cockerel" (1834); 2 chapters of Washington Irving's Tales of the Alhambra |

| Premiere |

7 October 1909 Solodovnikov Theatre , Moscow, Russia |

The Golden Cockerel (Russian: Золотой петушок, Zolotoy petushok) is an opera in three acts, with short prologue and even shorter epilogue, by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Its libretto, by Vladimir Belsky, derives from Alexander Pushkin's 1834 poem The Tale of the Golden Cockerel, which in turn is based on two chapters of Tales of the Alhambra by Washington Irving. The opera was completed in 1907 and premiered in 1909 in Moscow, after the composer's death. Outside Russia it has often been performed in French as Le coq d'or.

Composition history

Rimsky-Korsakov had considered his previous opera, The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya (1907) to be his final artistic statement in the medium, and, indeed, this work has been called a "summation of the nationalistic operatic tradition of Glinka and The Five."[1] However the political situation in Russia at the time inspired him to take up the pen to compose a "razor-sharp satire of the autocracy, of Russian imperialism, and of the Russo-Japanese war."[2]

(1799–1837)

Four factors influenced Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov to write this opera-ballet:

- Pushkin – Rimsky-Korsakov’s other works inspired by Alexander Pushkin's poems, especially Tsar Saltan, had been very successful. The Golden Cockerel had the same magic.

- Bilibin – Ivan Bilibin had already produced artwork for the Golden Cockerel, and this conjured up the same traditional Russian folk flavours as those in Tsar Saltan.

- Russo-Japanese War – Under Tsar Nikolay II, Russia became involved in a war with Japan. This war was highly unpopular amongst the Russian people. It proved to be a military disaster, and Russia was eventually defeated. (In the Golden Cockerel, Tsar Dodon foolishly decides to make a pre-emptive strike against the neighbouring state, and there is huge chaos and bloodshed on the battlefield. The tsar himself gives more attention to his personal pleasures, and comes to a sticky end.)

- Russian Revolutionary Activity in 1905 – Many Russian people were not only upset by the Russo-Japanese War, but also by poor living conditions. On January 9, 1905, several thousand people, led by a priest, demonstrated peacefully in the Palace Square in Sankt-Peterburg. They tried to hand in a petition asking for better working conditions, an eight-hour day, a minimum wage, and the prohibition of child labour. However, more than 1,000 persons were shot by the Tsarist troops, and the date has become known as Bloody Sunday. News of this massacre spread rapidly – there was an uprising in Odessa, where the sailors in the battleship Potemkin took over the ship and fired on the headquarters of the tsarist troops. Again, there was a massacre of people on the Odessa steps. The Students in the Sankt-Peterburg Conservatoire also demonstrated against the Tsar, and Rimsky-Korsakov supported their protest. For this he was dismissed from his post as head of the Conservatoire. Alexander Glazunov and Anatoly Lyadov resigned and left with him. See also Russian Revolution of 1905.

Rimsky-Korsakov started work on his Golden Cockerel opera. It was finished in 1907. The opera was immediately banned by the Palace, and was not allowed to be staged. Rimsky-Korsakov’s health was probably affected by this, and he was dead by the time it was performed two years later.

Performance history

The premiere took place on 7 October (O.S. 24 September) 1909, at Moscow's Solodovnikov Theatre in a performance by the Zimin Opera. Emil Cooper conducted; set designs were by Ivan Bilibin. The opera was given at the city's Bolshoi Theatre a month later, on 6 November, conducted by Vyacheslav Suk and with set designs by Konstantin Korovin. London and Paris premieres occurred in 1914; in Paris it was staged at the Palais Garnier by the Ballets Russes as an opera-ballet, choreographed and directed by Michel Fokine with set and costume designs by Natalia Goncharova.[3][4] The United States premiere took place at the Metropolitan Opera House on 6 March 1918, with Marie Sundelius in the title role, Adamo Didur and Maria Barrientos in the actual leads, and Pierre Monteux conducting.

The Met performed the work regularly through 1945. All Met performances before World War II were sung in French; during the work's final season in the Met repertory, the Golden Cockerel was sung in English. The work has not been performed at the Met since the war, but it was staged at neighboring New York City Opera from 1967 to 1971, always in English, with Beverly Sills singing the Tsaritsa of Shemakha opposite Norman Treigle's Dodon, and Julius Rudel conducting Tito Capobianco's production.

On 13 December 1975 the BBC broadcast a live performance in English from the Theatre Royal Glasgow with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Alexander Gibson, and with Don Garrard as Tsar Dodon, John Angelo Messana as the Astrologer and Catherine Gayer as the Tsaritsa.

The Mariinsky Theatre staged a new production of The Golden Cockerel on 25 December 2014, with Valery Gergiev as conductor. The stage director and costume designer was Anna Matison. The opera was presented in Russian during the 2015 winter season by the Sarasota Opera conducted by Ekhart Wycik, with set designs by David P. Gordon, and featuring Grigory Soloviov as Tsar Dodon, Alexandra Batsios as the Tsaritsa of Shemakha, Timur Bekbosunov at the Astrologer, and Riley Svatos as the Golden Cockerel.

Instrumentation

- Strings: Violins, Violas, Cellos, Double Basses

- Woodwinds: 1 Piccolo, 2 Flutes, 2 Oboes, 1 English Horn, 2 Clarinets (in A-B), 1 Bass Clarinet (in A-B), 2 Bassoons, 1 Double Bassoon

- Brass: 4 French Horns (in F), 2 Trumpets (in C), 1 Trumpet contralto (in F), 3 Trombones, 1 Tuba

- Percussion: Timpani, Triangle, Snare Drum, Tambourin, Glockenspiel, Cymbals, Bass Drum, Xylophone, Tam-tam

- Other: Celesta, 2 Harps

Roles

| Roles | Voice type | Performance cast Zimin Opera 24 September 1909 (Conductor: Emil Cooper) |

Performance cast Bolshoi Theatre 6 November 1909 (Conductor: Vyacheslav Suk) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tsar Dodon (Царь Додон) | bass | Nikolay Speransky | Vasily Osipov |

| Tsarevich Gvidon (Царевич Гвидон) | tenor | Fyodor Ernst | Semyon Gardenin |

| Tsarevich Afron (Царевич Афрон) | baritone | Andrey Dikov | Nikolay Chistyakov |

| General Polkan | bass | Kapiton Zaporozhets | |

| Amelfa, a housekeeper | contralto | Aleksandra Rostovtseva | Serafima Sinitsina |

| Astrologer | tenor altino | Vladimir Pikok | Anton Bonachich |

| Tsaritsa of Shemakha (Шемаханская царица) | coloratura soprano | Avreliya-Tsetsiliya Dobrovolskaya | Antonina Nezhdanova |

| Golden Cockerel (Золотой петушок) | soprano | Vera Klopotovskaya | Yevgeniya Popello-Davydova |

| chorus, silent roles | |||

Note on names:

- Pushkin spelled Dodon's name as Dadon. The association of the revised spelling Dodon in the libretto with the dodo bird is likely intentional.

- Shemakha is a noun, denoting a place. Shemakhan is an adjectival usage.

Synopsis

Time: Unspecified

Place: In the thrice-tenth tsardom, a far off place (beyond thrice-nine lands) in Russian fairy tales

Note: There is an actual city of Shemakha (also spelled "Şamaxı", "Schemacha" and "Shamakhy"), which is the capital of the Shamakhi Rayon of Azerbaijan. In Pushkin's day it was an important city and capital of what was to become the Baku Governorate. But the realm of that name, ruled by its tsaritsa, bears little resemblance to today's Shemakha and region; Pushkin likely seized the name for convenience, to conjure an exotic monarchy.

Prologue

After quotation by the orchestra of the most important leitmotifs, a mysterious Astrologer comes before the curtain and announces to the audience that, although they are going to see and hear a fictional tale from long ago, his story will have a valid and true moral.

Act 1

The bumbling Tsar Dodon talks himself into believing that his country is in danger from a neighbouring state, Shemakha, ruled by a beautiful tsaritsa. He requests advice of the Astrologer, who supplies a magic Golden Cockerel to safeguard the tsar's interests. When the little cockerel confirms that the Tsaritsa of Shemakha does harbor territorial ambitions, Dodon decides to pre-emptively strike Shemakha, sending his army to battle under the command of his two sons.

Act 2

However, his sons are both so inept that they manage to kill each other on the battlefield. Tsar Dodon then decides to lead the army himself, but further bloodshed is averted because the Golden Cockerel ensures that the old tsar becomes besotted when he actually sees the beautiful Tsaritsa. The Tsaritsa herself encourages this situation by performing a seductive dance – which tempts the Tsar to try and partner her, but he is clumsy and makes a complete mess of it. The Tsaritsa realises that she can take over Dodon’s country without further fighting – she engineers a marriage proposal from Dodon, which she coyly accepts.

Act 3

The Final Scene starts with the wedding procession in all its splendour. As this reaches its conclusion, the Astrologer appears and says to Dodon, “You promised me anything I could ask for if there could be a happy resolution of your troubles ... .” “Yes, yes,” replies the tsar, “Just name it and you shall have it.” “Right,” says the Astrologer, “I want the Tsaritsa of Shemakha!” At this, the Tsar flares up in fury, and strikes down the Astrologer with a blow from his mace. The Golden Cockerel, loyal to his Astrologer master, then swoops across and pecks through the Tsar’s jugular. The sky darkens. When light returns, tsaritsa and little cockerel are gone.

Epilogue

The Astrologer comes again before the curtain and announces the end of his story, reminding the public that what they just saw was “merely illusion,” that only he and the tsaritsa were mortals and real.

Principal arias and numbers

- Act 1

- Introduction: "I Am a Sorcerer" «Я колдун» (orchestra, Astrologer)

- Lullaby (orchestra, guards, Amelfa)

- Act 2

- Aria: "Hymn to the Sun" «Ответь мне, зоркое светило» (Tsaritsa of Shemakha)

- Dance (Tsaritsa of Shemakha, orchestra)

- Chorus (slaves)

- Act 3

- Scene: "Wedding Procession" «Свадебное шествие» (Amelfa, people)

Analysis

Preface to The Golden Cockerel by librettist V. Belsky (1907)

The purely human character of Pushkin's story, The Golden Cockerel – a tragi-comedy showing the fatal results of human passion and weakness – allows us to place the plot in any surroundings and in any period. On these points the author does not commit himself, but indicates vaguely in the manner of fairy-tales: "In a certain far-off tsardom", "in a country set on the borders of the world".... Nevertheless, the name Dodon and certain details and expressions used in the story prove the poet's desire to give his work the air of a popular Russian fairy tale (like Tsar Saltan), and similar to those fables expounding the deeds of Prince Bova, of Jerouslan Lazarevitch or Erhsa Stchetinnik, fantastical pictures of national habit and costumes. Therefore, in spite of Oriental traces, and the Italian names Duodo, Guidone, the tale is intended to depict, historically, the simple manners and daily life of the Russian people, painted in primitive colours with all the freedom and extravagance beloved of artists.

In producing the opera the greatest attention must be paid to every scenic detail, so as not to spoil the special character of the work. The following remark is equally important. In spite of its apparent simplicity, the purpose of The Golden Cockerel is undoubtedly symbolic.

This is not to be gathered so much from the famous couplet: "Tho' a fable, I admit, moral can be drawn to fit!" which emphasises the general message of the story, as from the way in which Pushkin has shrouded in mystery the relationship between his two fantastical characters: The Astrologer and the Tsaritsa.

Did they hatch a plot against Dodon? Did they meet by accident, both intent on the tsar's downfall? The author does not tell us, and yet this is a question to be solved in order to determine the interpretation of the work. The principal charm of the story lies in so much being left to the imagination, but, in order to render the plot somewhat clearer, a few words as to the action on the stage may not come amiss.

Many centuries ago, a wizard, still alive today sought, by his magic cunning to overcome the daughter of the Aerial Powers. Failing in his project, he tried to win her through the person of Tsar Dodon. He is unsuccessful and to console himself, he presents to the audience, in his magic lantern the story of heartless royal ingratitude.

Performance practice

(Solodovnikov Theatre, Moscow, 1909)

Composer's Performance Remarks (1907)

- The composer does not sanction any "cuts."

- Operatic singers are in the habit of introducing interjections, spoken words, etc. into the music, hoping thereby to produce dramatic, comic or realistic effect. Far from adding significance to the music, these additions and emendations merely disfigure it. The composer desires that the singers in all his works keep strictly to the music written for them.

- Metronome marks must be followed accurately. This does not imply that artists should sing like clock-work, they are given full artistic scope, but they must keep within bounds.

- The composer feels it necessary to reiterate the following remark in lyrical passages, those actors who are on the stage, but not singing at the moment, must refrain from drawing the attention of the spectators to themselves by unnecessary by-play. An opera is first and foremost a musical work.

- The part of the Astrologer is written for a voice seldom met with, that of tenor altino. It may however be entrusted to a lyric tenor possessing a strong falsetto, for the part is written in the extremely high register.

- The Golden Cockerel demands a strong soprano or high mezzo-soprano voice.

- The dances performed by the Tsar and Tsaritsa in the second act, must be carried out so as not to interfere with the singers breathing by too sudden or too violent movement.

Staging Practices

Early stagings became influential by stressing the modernist elements inherent in the opera. Diaghilev's 1914 Paris production had the singers sitting offstage, while dancers provided the stage action.[1] Though some in Russia disapproved of Diaghilev's interpretation, and Rimsky-Korsakov's widow threatened to sue, the production was considered a milestone. Stravinskiy was to expand on this idea in the staging of his own Renard (1917) and Les Noces (1923), in which the singers are unseen, and mimes or dancers perform on stage.[5]

Derived works

Rimsky-Korsakov made the following concert arrangement:

- Introduction and Wedding Procession from the opera The Golden Cockerel (1907)

- Введение и свадебное шествие из оперы «Золотой петушок»

After his death, A. Glazunov and M. Shteynberg (Steinberg) compiled the following orchestral suite:

- Four Musical Pictures from the Opera The Golden Cockerel

- Четыре музыкальных картины из оперы «Золотой петушок»

- Tsar Dodon at home (Царь Додон у себя дома)

- Tsar Dodon on the march (Царь Додон в походе)

- Tsar Dodon with the Shemakhan Tsaritsa (Царь Додон у Шемаханской царицы)

- The wedding and the lamentable end of Dodon (Свадьба и печальный конец Додона)

Efrem Zimbalist wrote Concert Phantasy on 'Le coq d'or' for violin and piano based on themes from the suite.

Inspiration for other works

Marina Frolova-Walker points to The Golden Cockerel as the fore-runner of the anti-psychologistic and absurdist ideas which would culminate in such 20th century 'anti-operas' as Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges (1921) and Shostakovich's The Nose (1930). In this, his last opera, Rimsky-Korsakov had laid "the foundation for modernist opera in Russia and beyond."[1]

In 1978–79 the English composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji wrote "Il gallo d’oro" da Rimsky-Korsakov: variazioni frivole con una fuga anarchica, eretica e perversa.

Recordings

Audio Recordings (Mainly studio recordings, unless otherwise indicated)

Source: www.operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- 1962, Aleksey Korolev (Tsar Dodon), Yuri Yelnikov (Tsarevich Gvidon), Aleksandr Polyakov (Tsarevich Afron), Leonid Ktitorov (General Polkan), Antonina Klescheva (Amelfa), Gennady Pishchayev (Astrologer), Klara Kadinskaya (Shemakhan Tsaritsa), Nina Polyakova (Golden Cockerel). Moscow Radio Orchestra and Chorus. ' Aleksey Kovalev & Yevgeny Akulov (conductor).

- 1971 (sung in English, live performance), Norman Treigle (Tsar Dodon), Beverly Sills (Tsaritsa Shemakha), Enrico di Giuseppe (Astrologer), Muriel Costa-Greenspon (Amelfa), Gary Glaze (Gvidon), David Rae Smith (Afron), Edward Pierson (Polkan), Syble Young (Le Coq d’or). Orchestra and Chorus of the New York City Opera. Julius Rudel

- 1985, Nikolai Stoilov (Tsar Dodon), Ljubomir Bodurov (Tsarevich Gvidon), Emil Ugrinov (Tsarevich Afron), Kosta Videv (General Polkan), Evgenia Babacheva (Amelfa), Lyubomir Diakovski (Astrologer), Elena Stoyanova (Shemakhan Tsaritsa), Yavora Stoilova (Golden Cockerel). Sofia National Opera Orchestra and Chorus, Dimiter Manolov.

- 1988, Yevgeny Svetlanov (conductor), Bolshoy Theatre Orchestra and Chorus, Artur Eisen (Tsar Dodon), Arkady Mishenkin (Tsarevich Gvidon), Vladimir Redkin (Tsarevich Afron), Nikolay Nizinenko (General Polkan), Nina Gaponova (Amelfa), Oleg Biktimirov (Astrologer), Yelena Brilova (Shemakhan Tsaritsa), Irina Udalova (Golden Cockerel)

- Notable excerpts

- 1910 Antonina Nezhdanova (Shemakhan Tsaritsa): Hymn to the Sun (in Russian). Available on LP, CD, online.

Videos

- 1986 Grigor Gondjian (Tsar Dodon), Ruben Kubelian (Tsarevich Gvidon), Sergey Shushardjian (Tsarevich Afron), Ellada Chakhoyan (Queen of Shemakha), Susanna Martirosian (Golden Cockerel), Haroutun Karadjian (General Polkan), Grand Aivazian (Astrologer). Alexander Spendiaryan State Academic Theatre Orchestra, Yerevan, Aram Katanian.

- 2002 Albert Schagidullin (Tsar Dodon), Olga Tifonova (Tsaritsa), Barry Banks (Astrologer) Orchestre de Paris, Kent Nagano

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 Frolova-Walker, Marina (2005). "11. Russian opera; The first stirrings of modernism". In Mervyn Cooke. The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 0-521-78393-3.

- ↑ Maes, Francis; Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans (translators) (2002) [1996]. "8. "A Musical Conscience" Rimsky-Korsakov and the Belyayev Circle". A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-520-21815-9. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "News in brief: Visitors to Drury Lane." The Times (London), 23 July 1914, p. 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web, accessed 13 April 2016 (subscription necessary).

- ↑ Garafola, Lynn (1989). Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. New York, Oxford University Press, p. 390. ISBN 0-19-505701-5

- ↑ Maes, Francis; Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans (translators) (2002) [1996]. "8. "Russia's Loss" The Musical Emigration". A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 275. ISBN 0-520-21815-9. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help)

- Sources

- Abraham, Gerald (1936). "XIV. – The Golden Cockerel". Studies in Russian Music. London: William Reeves / The New Temple Press. pp. 290–310.

- Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam, 2001. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

External links

- https://archive.org/details/lecoqdor Metropolitan Opera House libretto of Le Coq d'Or

- Libretto at Google Books

- Pushkin's tale of The Golden Cockerel

- Commentary on Pushkin's poem

- KBAQ FM analysis of a 2002 performance