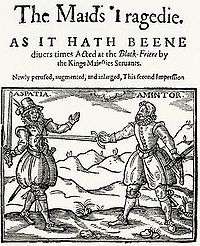

The Maid's Tragedy

The Maid's Tragedy is a play by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. It was first published in 1619.

The play has provoked divided responses from critics.

Date

The play's date of origin is not known with certainty. In 1611, Sir George Buck, the Master of the Revels, named The Second Maiden's Tragedy based on the resemblances he perceived between the two works. Scholars generally assign the Beaumont/Fletcher play to c. 1608–11.

Authorship

Scholars and critics generally agree that the play is mostly the work of Beaumont; Cyrus Hoy, in his extensive survey of authorship problems in the Beaumont/Fletcher canon, assigns only four scenes to Fletcher (Act II, scene 2; Act IV, 1; and Act V, 1 and 2), though one of those is the climax of the play (IV, 1).[1]

Publication

The play was entered into the Stationers' Register on 28 April 1619, and published later that year by the bookseller Francis Constable. Subsequent editions appeared in 1622, 1630, 1638, 1641, 1650, and 1661. The play was later included in the second Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1679.[2]

The texts of the first quarto of 1619, and the second of 1622, are usually synthesized to create modern editions, since Q2 contains eighty lines not included in Q1, plus a couple of hundred changes and corrections on Q1.

Synopsis

Melantius, a young general, returns from a military campaign which he has just concluded, winning peace for Rhodes. He is greeted by the King’s brother, Lysippus. Menantius expects to have returned to witness the wedding of his friend Amintor with Aspatia, his betrothed, but instead the King has ordered Amintor to marry Melantius’s sister, Evadne, in order to honour her brother’s military achievements. Aspatia is very melancholy at this, but the whole court is about to celebrate the wedding with a masque.

Aspatia’s aged father Calianax and a servant are attempting to keep the populace out of the palace as the masque is for the court alone. Calianax has been ‘humorous’ since his daughter’s wedding was broken off and quarrels with Melantius and then with Amintor. The masque of Night and Cynthia (the Moon) is held with various songs, and Evadne and Amintor are taken to their wedding chamber.

Outside the chamber Evadne’s maid Dula jokes bawdily with her mistress, but Aspatia cannot join in the banter and announces she will die of grief, taking a last farewell of Amintor when he enters. Left alone with her husband Evadne refuses to sleep with him and eventually reveals that the King has forcibly made her his mistress and has arranged this marriage to cover up her ‘dishonour’. Amintor is horrified, but agrees to go through with the charade of pretending to be a married couple. He sleeps on the floor. Aspatia is talking with her maids, advising them never to love. One of them has produced a tapestry of Theseus and Ariadne, a suitable theme for Aspatia’s plight. Calianax enters and is angry at the situation, breathing threats against the men of the court.

The morning after the wedding night some male courtiers are talking bawdily outside the chamber and are joined by Melantius. Evadne and Amintor emerge and continue with the pretense, but Amintor is so distressed he says various strange things and Melantius and Evadne notice. The King and courtiers enter and he quizzes the couple; Amintor’s answers are so smooth that the King grows jealous and he dismisses everyone except Evadne and Amintor. He satisfies himself that the couple have not slept together and he lets Amintor know the rules: he is to allow Evadne to come to him whenever he wants and is to stay away from her himself.

Melantius enters and quarrels with Calianax again; after he leaves, not daring to challenge Melantius, Amintor enters and Melantius gets the secret out of him. He dissuades his friend from revenge and counsels patience, but once Amintor has left he begins to plot to kill the King. In order to do this he has to have control of the citadel which is governed by Calianax. The old man enters again and Melantius proposes common revenge for the injuries that the King has done them both, but after he leaves Calianax resolves to go straight to the King with this information. Melantius goes to Evadne and forces her to reveal what has happened. He gets her to promise to kill the King. He leaves and Amintor enters, Evadne apologises for the situation, but doesn’t reveal she is to kill the King.

Calianax has told the King of Melantius’ plot, however the King has difficulty believing him. In the ensuing scene with the whole court, Meliantius easily outfaces Calianax’s accusations and leaves him looking foolish. When everyone except these two leave, Calianax tells Melantius he has no option but to go along with the plot and hand over the citadel. Melantius expects Evadne to kill the King that night, but at this point Amintor enters talking wildly of revenge and Melantius has to pretend that none is planned.

The King has summoned Evadne, but when she arrives at his bed chamber she finds him asleep. She soliloquises and then ties his arms to the bed. She wakes him and tells him she is going to kill him for his rape of her. The King doesn’t believe her, but she stabs him, makes sure he is dead, then leaves. The King’s body is discovered and his brother Lysippus is proclaimed the new King. Melantius, his brother Diphilus, and the unwilling Calianax are standing on the citadel explaining to the populace why the King was killed. The new King enters, and after some negotiation the three agree to give up the citadel in return for a pardon.

Aspatia enters the palace dressed as a man seeking Amintor. When she finds him she pretends to be a brother of hers looking to fight Amintor to avenge the insult offered to his sister. After much provocation she gets him to fight, but during the fight she drops her guard deliberately and is fatally wounded. Evadne then enters with the bloody knife and asks Amintor to take her as his wife in actuality. He hesitates, leaves, and she stabs herself. He reenters to find her dead and the dying Aspatia reveals herself. He then stabs himself and dies.

Finally Melantius, the new King, and the court enter and discover the bodies; Melantius tries to kills himself too but is restrained. He promises to starve himself to death instead. The new King promises to rule ‘with temper’.

Critical responses

Critics have varied widely, even wildly, in their responses to the play. Many have recognized the play's power, but have complained about the play's extremity and artificiality. (People who dislike aspects of Beaumont and Fletcher's work will find those dislikes amply represented, even crystallized, in this play.) John Glassner once wrote that to display "the insipidity of the plot, its execrable motivation or the want of it, and the tastelessness of many of the lines one would have to reprint the play."[3]

Andrew Gurr, one of the play's modern editors, notes that the play "has that anomaly amongst Elizabethan tragedies, an original plot." Other critics have noted that the play introduces romance into the standard revenge tragedy, and that the play, even in its artificiality, has relevance to the disputes about authority that characterized relations between kings and Parliament in the decades leading up to the English Civil War.[4] Due to its setting on the island of Rhodes, the play has also been read in light of sixteenth-century Ottoman military expansion in the Mediterranean.[5]

References

- ↑ Cyrus Hoy, "The Shares of Fletcher and His Collaborators in the Beaumont and Fletcher Canon," Studies in Bibliography, VIII-XV, 1956-62.

- ↑ E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 3, p. 224.

- ↑ Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds., The Later Jacobean and Caroline Dramatists: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1978; p. 25.

- ↑ Logan and Smith, pp. 26-7.

- ↑ Lindsay Ann Reid, Beaumont and Fletcher's Rhodes: Early Modern Geopolitics and Mythological Topography in The Maid's Tragedy, Early Modern Literary Studies 16.2 (2012)

External links

- Full text in Gutenberg Project

- Article from Literary Encyclopedia

-

The Maid's Tragedy public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Maid's Tragedy public domain audiobook at LibriVox