Thomas Satterwhite Noble

| Thomas Satterwhite Noble | |

|---|---|

Thomas Satterwhite Noble (undated photo) | |

| Born |

May 29, 1835 Lexington, Kentucky |

| Died |

April 27, 1907 (aged 71) New York, New York |

| Resting place | Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Oliver Frazier, George P. A. Healey, Thomas Couture |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work |

The Modern Medea (1867) The Price of Blood (1868) The Sibyl (1896) |

Thomas Satterwhite Noble (May 29, 1835 – April 27, 1907) was an American painter as well as the first head of the McMicken School of Design in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Biography

Noble was born in Lexington, Kentucky, and raised on a plantation where hemp and cotton were grown. He showed an interest and propensity for art at an early age. He first studied painting with Samuel Woodson Price in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1852 and then continued his studies with Price, Oliver Frazier and George P.A. Healey at Transylvania University in Lexington. In 1853 he moved to New York, New York, before moving to Paris to study with Thomas Couture from 1856 to 1859[1].

Noble then returned to the United States in 1859 intending on beginning his art career. However, with the beginning of the Civil War, as a Southerner, he served in the Confederate army from 1862 to 1865. After the war, Noble was paroled to St. Louis and began painting. With the success of his first painting, Last Sale of the Slaves, he received sponsorship from wealthy Northern benefactors for a studio in New York City. Noble lived in New York city from 1866 to 1869, during which time he painted some of his most well known oil paintings. In 1869, he was invited to become the first head of the McMicken School of Design in Cincinnati, Ohio, a post he would hold until 1904. In 1887, the McMicken School of Design became the present-day Art Academy of Cincinnati. During his tenure at the McMicken School of Design, Noble moved briefly to Munich, Germany, where he studied from 1881 to 1883[1]. He retired in 1904 and died in New York City on April 27, 1907. He is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.[2]

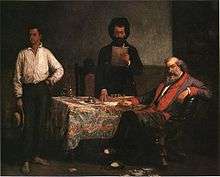

Noble's well-known works are largely historical or social/political presentations. He is best known for a series of four anti-slavery paintings. The first, Last Sale of the Slaves (1865) depicted a the scene of the last sale of the slaves on the St. Louis courthouse steps. He then followed this painting with John Brown's Blessing (1866) which depicted the abolitionist activist John Brown being led to his execution and blessing a child on the steps of the courthouse. His third painting, The Modern Medea (1867) portrayed the tragic event from 1856 in which Margaret Garner, a fugitive slave mother, murdered her children rather than see them returned to slavery. The picture is notable for Garner's expression of rage and including the white slave hunters in the imagery. Noble's last painting, Price of Blood (1868), was not based on a specific historical event, but depicted a white slave owner selling his half-white slave son. Noble said of this painting that "this picture will be regarded as one of the powerful lights that I have thrown into the dark night of slavery. One of the most thundering denunciations of man's inhumanity to man"[3] As with The Modern Medea, this painting is unique for the era with the inclusion of the white perpetrators in the imagery[4].

Exhibitions and major works

Noble's artwork has been exhibited in over 70 exhibitions, both during his lifetime and after his death. Most of Noble's well-know initial works are historical presentations, painted to make strong political and moral commentary. Later in in his life he painted many allegorical images, often using his children to pose for figures in the paintings. After studying in Munich and towards the end of his life, Noble focused his artistic work on landscapes of Ohio and Kentucky countryside and Bensonhurst New York[4]. Noble's most well known paintings are Last Sale of the Slaves, John Brown's Blessing, Price of Blood and Margaret Garner. Each painting depicts a specific horror of slavery: In Last Sale of the Slaves, the selling of a mother and child; in Price of Blood, the selling of a son by the slave owner; In Margaret Garner, a mother killing her children rather than subjecting them to slavery. Noble also sketched a well-known lithograph for Harper's weekly based on his John Brown's Blessing[5].

- 1866 St. Louis, MO Pettes and Leathe Gallery

- 1866 New York, NY National Academy of Design, 7th Annual Exhibition pf the Artist's Fund Society

- 1866 New York, NY National Academy of Design, 41st Annual Exhibition

- 1866 Boston, MA DeVries Ibarra and Co.

- 1867 New York, NY National Academy of Design, 42nd Annual Exhibition

- 1867 Boston, MA Childs and Co.

- 1867 Washington, DC United State Capital

- 1867 St. Louis, MO Pettes and Leathe Gallery

- 1867–68 Chicago, IL Opera House Art Gallery

- 1868 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Academy of Fine Arts, Wiswell's Gallery

- 1868 New York, NY National Academy of Design, 43rd Annual Exhibition

- 1869 Boston, MA Williams and Everett Gallery

- 1868–69 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Academy of Fine Arts, Wiswell's Gallery

- 1869 Philadelphia, PA Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 46th Annual ExhibitioN

- 1870 Cincinnati, OH Wiswell's Gallery

- 1870 Cincinnati, OH 1st Cincinnati Industrial Exposition

- 1870 New York, NY National Academy of Design, 45th Annual Exhibition

- 1871 Cincinnati, OH Wiswell's Gallery

- 1871 New York, NY National Academy of Design, 46th Annual Exhibition

- 1872 Cincinnati, OH 3rd Cincinnati Industrial Exposition

- 1873 Cincinnati, OH McMicken School of Design, 3rd Annual Exhibition

- 1874 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Industrial Exposition

- 1875 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Industrial Exposition

- 1875 Chicago, IL Chicago Academy of Design

- 1875 Glasgow, Scotland James McCure and Sons, 14 Gordon Street

- 1876 Philadelphia, PA Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition Art Gallery and Annex

- 1877 Cincinnati, OH Wiswell's Gallery

- 1878 Cincinnati, OH Women's Art Association, Loan Collection Exhibition

- 1879 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Industrial Exposition

- 1880 Chicago, IL Chicago Academy of Design

- 1887 Indianapolis, IN Indianapolis Art Association, 4th Annual Exhibition

- 1888 Chicago, IL Chicago Art Institute, 1st Annual Exhibition of American Oil Paintings

- 1891 Cincinnati, OH Piper Gallery, 2nd Exhibition of the Cincinnati Art Club

- 1894–95 Lexington, KY Lexington Manufacturer's Exposition, Art Loan Gallery

- 1895 Atlanta, GA Cotton States and International Exhibition

- 1895 Cincinnati, OH Spring Exhibition of the Cincinnati Museum Association

- 1896 Cincinnati, OH Spring Exhibition of the Cincinnati Museum Association

- 1896 Cincinnati, OH Music Hall, Loan Exhibition of Portraits

- 1896 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, Loan Exhibition of Portraits

- 1896–97 Pittsburgh, PA Carnegie Art Galleries, 1st Annual Exhibition

- 1896 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, Exhibition of Studies, Sketches, and Pictures in Watercolors

- 1897 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, 2nd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1897–98 Detroit, MI Detroit Museum of Art, 2nd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1898 Chicago, IL Art Institute of Chicago, 2nd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1898 Indianapolis, IN Indianapolis Propylaeum, 2nd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1898 Detroit, MI Detroit Museum of Art, 3rd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1898–99 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, 3rd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1899 Indianapolis, IN Indianapolis Art Association, 3rd Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists

- 1899 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, 6th Annual Exhibition of American Art

- 1900 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, 7th Annual Exhibition of American Art

- 1901 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Fall Festival

- 1905 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Business Men's Club

- 1906 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, 13th Annual Exhibition of American Art

- 1907 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, Exhibition of the Work of the Late Thomas S. Noble

- 1908 Chicago, IL Chicago Art Institute, Paintings of Thomas S. Noble 1835-1907

- 1908 St. Louis, MO St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts, Paintings by Thomas S. Noble, et al.

- 1910 New York, NY Ralston Galleries, Paintings by Thomas S. Noble

- 1915 San Francisco, CA Panama-Pacific International Exposition, Department of Fine Arts

- 1923 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, Special Exhibition of Former Cincinnati Artists

- 1937–38 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, 50th Anniversary Exhibition of Work by Teachers and Former Students of the Art Academy

- 1970 College Park, MD University of Maryland Art Gallery, American Pupils of Thomas Couture

- 1979–80 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, The Golden Age: Cincinnati Painters of the 19th Century Represented in the Cincinnati Art Museum

- 1981 Lexington, KY University of Kentucky Art Museum, The Kentucky Painter: From the Frontier Era to the Great War

- 1984 Owensboro, KY Owensboro Museum of Fine Arts, Kentucky Expatriates: Natives and Notable Visitors

- 1987 Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Art Museum, The Procter & Gamble Art Collection

- 1987 New York, NY Phillips Gallery, Look Away, Reality and Sentiment in Southern Art

- 1987 New York, NY ACA Gallery, Visions of America 1787-1987: 200 Years of American Genre Painting in Commemoration of the Bicentennial of the US Constitution

- 1988 Lexington, KY University of Kentucky Art Museum, Thomas S. Noble 1835-1907

- 1988 Greenville, SC Greenville County Museum of Art, Thomas S. Noble 1835-1907

- 1988 Cincinnati, OH Art Academy of Cincinnati, Thomas S. Noble 1835-1907

- 1990 Washington, DC Corcoran Gallery, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art, 1710-1940

- 1990 Brooklyn, NY Brooklyn Museum of Art, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art, 1710-1940

- 2016 Highland Heights, KY Northern Kentucky University, Steely Library

Major museum/collection holdings[6]

- Allen Memorial Art Museum: The Present (1865)

- Chazen Museum of Art: Grandfather's Story (80th Birthday, The Old Sailor) (1895)

- Cincinnati Art Museum: Back to School (1859), Ohio Landscape (1890), Study Head of a Man (1865), Portrait of Joseph Longworth (1894), Portrait of David Sinton (1896), Landscape near T.S. Noble's House on Kemper Lane (unknown)

- The Filson Historical Society: Study for a Figure in Witch Hill (possibly self-portrait) (1867)

- Greenville County Museum of Art: The Sybil (1896), Cleaning Antiques (1904), Fugitives in Flight (1869)

- The Johnston Collection: Forgiven (1872)

- Kentucky Historical Society: The Last Communion of Henry Clay (1870) (also attributed to Robert Walker Weir)

- Missouri Historical Society: The Last Sale of Slaves in St. Louis (1870)

- Morris Museum: Price of Blood (1868)

- National Academy of Design: Self Portrait (unknown)

- New York Historical Society: John Brown's Blessing (1867) and Witch Hill (1869)

- Underground Railroad Museum: Margaret Garner (The Modern Medea) (1867)

- Yale University Art Gallery: Blind Man of Paris (1895), Still Life-A Potted Plant (1875), Man in Brown Suite (from behind) (1870s)

Correspondence[8]

Art historians and scholars have speculated on the motivations for Noble depicting such political scenes and commentary in his most well known works. A specific focus has been on that Noble was a Southerner whose family owned slaves and who served in the Confederate army and how these facts contradict the anti-slavery subject matter of his art. The discovery in 2015 of extensive correspondence by Thomas Noble written during the years 1865–1907 provides new insight into the motivations of the artist. In his letters, his clear opposition to slavery, the importance of a moral artistic philosophy, and his feeling of being an outsider in the South add a deeper understanding to the complexity of the motivations behind his art.[9]

From a letter to his future wife, Mary Caroline Hogan, April 11, 1868:

"I would rather take you to democratic New York, where men can think and act as deems best to them. Where we can have no one interfere with our religion or politics and we can do just as we please, no so in any other city. Without much annoyance from ignorant, meddlesome people who have the road of propriety chalked out and expect everyone to walk in it after a fashion prescribed by a select few. This will not suit me. I am not suited to any state other than perfect freedom. To think and speak and act just as I please".

From a letter to his future wife, Mary Caroline Hogan, December 1, 1867

"In coming among men of culture and taste, I have but come into my natural element in my works. I have displayed a power which wins their admiration and touches their hearts. I may meet with bitter opposition. Many bitter enemies. It would be strange if I did not…but I came not for that. I would rather have it than not. I wield a weapon mightier than the pen – I will silence them with my pencil. Nay no – attention to any adverse criticisms on me or my works. I know I am working in behalf of light".

As his correspondence is read and further analyzed, greater insight into the artistic and personal motivations of this 19th Century American artist and teacher will help better inform his legacy and the narrative of his role in American art.

References

- 1 2 3 Birchfield, James (1989). Thomas Satterwhite Noble, 1835-1907. University of Kentucky Press. p. 39.

- ↑ "Thomas Satterwhite Noble". Find A Grave. August 29, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ Personal Correspondence. Thomas Satterwhite Noble to his wife Mary Caroline Hogan Noble. 1867.

- 1 2 Morgan, Joanne (2007). "Thomas Satterwhite Noble's Mulattos: From Barefoot Madonna to Maggie the Ripper.". Journal of American Studies. Vol. 41. No. 1: Page 110 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Birchfield, James (1986). "Thomas S. Noble: "Made for a Painter" [Part II]". Kentucky Review. Vol. 6. No. 2: 53 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 "Thomas Satterwhite Noble". Ask Art. September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ Flemming, Tuliza Kamirah (2007). Thomas Satterwhite Noble (1835- 1907): Reconstructed Rebel. – via Drum.lib.umb.edu.

- ↑ Personal Correspondence and recollections collected from letters and correspondence held by direct descendants of Thomas Satterwhite Noble.

- ↑ Personal correspondence. Thomas Satterwhite Noble to his future wife Mary Caroline Hogan (1866-1868).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Satterwhite Noble. |