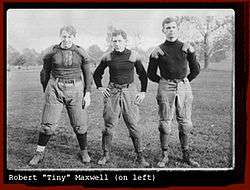

Tiny Maxwell

| |

| Position: | Guard |

|---|---|

| Personal information | |

| Date of birth: | September 7, 1884 |

| Place of birth: | Chicago, Illinois |

| Date of death: | June 30, 1922 (aged 37) |

| Place of death: | Norristown, Pennsylvania |

| Height: | 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) |

| Weight: | 240 lb (109 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school: | Englewood (IL) |

| College: | Chicago, Swarthmore |

| Career history | |

| |

Robert W. "Tiny" Maxwell (September 7, 1884 – June 30, 1922) was a professional football player and referee. He was also a sports editor with the Philadelphia Public Ledger.

Biography

Early life

Maxwell was born in Chicago, Illinois on September 7, 1884. He is known to have had a sister, named Katerine Doust at the time of his death.[1] Maxwell began his athletic career began at Englewood High School. There he excelled in football and track and field. He also played the mandolin and was a student actor in the school's Shakespearean plays.[2]

College

Before playing professional football, Maxwell played at the college level while attending the University of Chicago. He played for the Maroons in 1902, under coach Amos Alonzo Stagg, who recruited Maxwell for his size and style of play. Maxwell weighed 240 pounds, in an era when the average offensive lineman weighed under 200 pounds. Maxwell's struggle with a speech impediment made his physical presence less intimidating and in fact increased his popularity.[3] He played guard for the Maroons in 1902 and 1903. He also competed for the school as a boxer and in track and field, later set the school's record in the hammer throw. On July 4, 1904, Maxwell set the school's shot put record, when he recorded a 42'9" throw.[2]

In the fall of 1904, Maxwell transferred to Swarthmore College. There he prompted the interest of the school's president, who personally encouraged him to improve his studies and even directed the college treasurer to send his tuition bills to a member of the Swarthmore College Board of Managers.[4] It was around this time that he was given the nickname "Tiny". According to Amos Stagg, Maxwell was called "Fatty" while attending the University of Chicago. During his two years at Swarthmore, the school's football team went 6-3 in 1904 and 7-1 in 1905, losing only to the Penn.[2]

The bloodied face photo

In 1905, 18 players died playing college football and 159 were seriously injured. During an October 7, 1905 game between Swarthmore College and Penn, played at Franklin Field, Maxwell's nose was broken, his eyes were swollen nearly shut and his face dripped with blood. However Maxwell reportedly continue to play until near the end of the game, when his face was so bloody and swollen that he could no longer see, yet he never complained of the physical beating. Because of his size, Penn had three linemen block Maxwell. Swarthmore lost the game to Penn 11-4. [2]

According to legend, a newspaper photo was taken of his face. The photo then found its way to President Theodore Roosevelt. The photograph of Maxwell's face shocked and enraged the President into threatening to abolish football, if the colleges themselves did not take steps to eliminate the brutality and reduce injuries.[2]

"Swarthmore College stands for clean manly sport, shorn of all unnecessary roughness. President Roosevelt should have and I believe will have, the cordial support of the colleges and universities of the country... Let dangerous plays and ungentlemanly players be eliminated or let the game be eliminated from college life. Let college authorities see that only gentlemen are permitted to coach the teams and act as officials at the game. Football properly played and controlled is a good college recreation and sport, and it should be saved from its enemies. Swarthmore College will cooperate with others to secure clean college athletics."

—Joseph Swain, Swarthmore College President on President's Roosevelt's request[5]

Fact vs. fiction

Several writers and scholars have made exhaustive searches for the photo of Maxwell's battered face, but none have ever been found. Though the events surrounding the Roosevelt-Maxwell story supposedly occurred in 1905, the story didn't appear until it was mentioned in the second edition of Frank G. Menke's Encyclopedia of Sports published in 1944, 22 years after Maxwell's death. The 1960s and 1970s update of the Encyclopedia also continued to run the Maxwell-Roosevelt story. The Maxwell Football Club, formed by sportswriters and athletic officials to honor Maxwell, picked up the story and made it more credible. As a result, it became the official account of 1905 and was enshrined in Jack Falla’s history of the National Collegiate Athletic Association and is mentioned at the College Football Hall of Fame.[6]

What is absolutely certain is that on October 9, 1905, Teddy Roosevelt held a meeting of football representatives from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Though he lectured on the group on eliminating and reducing injuries, he never threatened to ban football or mentioned the Maxwell injury. He also lacked the authority to abolish football and was in fact, a fan of the game. At the time, the President's sons were also playing football at the college and secondary levels at the time.[6]

By December, sixty-two colleges agreed on a set of innovations that significantly changed the game of football. Yardage for a first down was changed from five to 10 yards; there was a neutral zone established between opposing lines, and the time of the game was reduced from 70 to 60 minutes. The year also saw the legalization of the forward pass.[2]

All-American honors

At the end of 1905 season two Swarthmore players were selected on Walter Camp's All-American team. One was their quarterback Wilmer Crowell, and the other was Maxwell. However Bob left Swarthmore in 1906 without receiving his degree.

Pro football

In the fall of 1906 Maxwell played professional football for the Massillon Tigers, later moving to the Canton Bulldogs of the Ohio League He then played for the Pittsburgh Lyceums after pro football disappeared from Ohio after the 1906 season. During this time, Maxwell insisted on wearing his Swarthmore jersey with its big "S" in all team pictures during his pro career.

1906 Canton-Massillon Scandal

In 1906 Maxwell was a figure in betting scandal between the Massillon Tigers and the Canton Bulldogs. The Canton Bulldogs-Massillon Tigers Betting Scandal was the first major scandal in professional football. It was more notably the first known case of professional gamblers' attempting to fix a professional sport. It refers to an allegation made by a Massillon newspaper charging the Bulldogs' coach, Blondy Wallace, and Tigers end, Walter East, of conspiring to fix a two game championship series between the two clubs. When the Tigers won the second a final game of a championship series and were named pro football's champions, Wallace was accused of throwing the game for Canton.[7][8]

However E. J. Stewart, the Tigers' coach and the editor of the Massillon Independent, charged that an actual attempt was made to bribe some of the Tiger players and that Wallace had been involved. His accusation was that an attempt had been made to bribe some Massillion players before the first game. According to Stewart, Tiny Maxwell and Bob Shiring of Massillon had been solicited to throw the first game by East. Maxwell and Shiring then reported the offer to the Tigers' manager and the scandal ended before it began. The scandal was said to have ruined professional football in Ohio until the mid 1910s.[8]

Coach

In 1909, Maxwell became an assistant coach for Swarthmore College. He later accepted an assistant coaching job at Penn. While coaching, Maxwell also enrolled at Jefferson Medical College, located in Philadelphia where he completed his pre-clinical studies. However he withdrew from the school after two years. As a student at Jefferson, Bob again played guard on the school's football team.[2]

Referee

Because of his tremendous size, quickness, and knowledge of the rules, Maxwell was soon in demand to officiate major games as Harvard-Yale, Army-Navy and Pitt-Penn State. Walter Camp later said that Maxwell set the standard for fairness and competence. He also officiated several professional football games as well. Bob worked the famed Penn-Dartmouth game at the Polo Grounds in 1919, referred to as "The Bloodiest Battle of World War I". Lou Little, a Penn tackle who later coached at Georgetown and Columbia, said Maxwell alone prevented an open riot.[2]

In 1921, Maxwell served as the referee for a game between the Union Quakers of Philadelphia and the pre-National Football League, Frankford Yellow Jackets.[9]

Notable officiating experiences

- During a Yale-Harvard game, Maxwell obstructed a Harvard tackler, preventing him from bringing down a Yale ball carrier. As Yale's players celebrated the resulting big gain, Maxwell told them, "Gentlemen of Yale, I fully expect to be invited to your annual banquet and be awarded my varsity 'Y.' I have j-just turned in the best Yale play of the day."[3]

- During a Pitt-Penn State game, after Maxwell had followed a Pitt runner for the length of the field in a breakaway play against Penn State, the Nittany Lions' captain insisted that the Pitt back had stepped out of bounds at his own 10-yard line. He then asked Tiny to come back with him to Pitt's 10 yard line, he'd point out the cleat mark. Maxwell responded by saying as he panted "Young man," if y-you want me to go back and look at that cleat mark, you'll have to hire me a t-taxi."[3]

- During a match-up involving a Catholic and non-Catholic college, a lineman for the Catholic institution bit the finger of one of the players from the non-Catholic school. When the bitten player complained, Maxwell replied, "I'll tell you what to do. Next year schedule the game on a Friday, because they don't eat meat then."[3]

Reporter

In 1914, after a journalistic apprenticeship in Chicago as a reporter for the Chicago Record Herald, he began writing a sports column for the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Two years later Maxwell became sports editor of the Public Ledger, a position he held until his death. Maxwell's column was reported as being stylish and good humored.[3] In friendly bet between Record Herald and a rival newspaper, Maxwell defeated his colleague in an eating contest.[1]

Death and legacy

"He was one of the finest football officials in the game and personally an ideal type of sportsman. I enjoyed his friendship and I believe that his writings have had a great influence upon athletics, especially for the promotion of cleaner athletics. The sports world can ill afford to lose him."

—Walter Camp, on the news of Maxwell's death[1]

Early in the summer of 1922, Maxwell and some friends went for a drive in the countryside north of Philadelphia. As they were returning that night, Maxwell noticed a car stopped directly in front of him on the road.[10] Fearing a holdup, he sped up to go around the car and ran head-on into a truck that was taking a group of Boy Scouts home from a picnic. According to Nan Pollock, one of those in Maxwell's party, Maxwell was pinned beneath the wreckage. He told his friends to "Help the others! I can wait."

Maxwell spent the next few days in a hospital located in Norristown, Pennsylvania, where he was suffering from seven broken ribs, a punctured lung and a dislocated hip. Pneumonia developed, and delirium soon followed. On the night of June 29, Maxwell was visited by his neighbor and close friend, Charles Heeb. Emerging from his delirium he talked of packing his bags and going home. "Take two hours' sleep, and I'll go with you," Heeb told him. Maxwell agreed and he drifted off to sleep where he later died.

In 1937, the Maxwell Football Club was founded in Philadelphia to award trophies in his name and promote football safety. The Club also annually awards the Maxwell Award to the best college football player in the nation, as determined by a panel of sportscasters, sportswriters, and NCAA head coaches and the membership of the Maxwell Football Club.[2]

He was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1974.

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Tiny Maxwell Dies from Motor Injuries". New York Times. New York Times Publishing (July 1): 10. July 1, 1922. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pagano, Ricard (1988). "Robert 'Tiny' Maxwell" (PDF). College Football Historical Society. LA 84 Foundation. 1 (4): 1–3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tiny Maxwell Cut A Wide Swath As A Football Player, Ref And Writer". Sports Illustrated; CNN: 1–3. November 12, 1984. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.swarthmore.edu/news/history/index3.html Swarthmore College History

- ↑ Pagano, Richard. "Robert "Tiny" Maxwell" (PDF). College Football Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- 1 2 Watterson, John (2001). "Tiny Maxwell and the Crisis of 1905: The Making of a Gridiron Myth" (PDF). College Football Historical Society. LA 84 Foundation: 54–57.

- ↑ Peterson, Robert W. (1997). Pigskin: The Early Years of Pro Football. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511913-4.

- 1 2 "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever" (PDF). PFRA Annual. Professional Football Researchers Association. 5: 1–16. 1984.

- ↑ http://home.comcast.net/~ghostsofthegridiron/Quakers2.htm/ Ghosts of the Gridiron Archived September 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- "Tiny Maxwell Dies from Motor Injuries". New York Times. New York Times Publishing (July 1): 10. July 1, 1922. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

References

- Peterson, Robert W. (1997). Pigskin: The Early Years of Pro Football. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511913-4.

- "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever" (PDF). PFRA Annual. Professional Football Researchers Association. 5: 1–16. 1984.

- "Tiny Maxwell Cut A Wide Swath As A Football Player, Ref And Writer". Sports Illustrated; CNN: 1–3. November 12, 1984. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- Pagano, Ricard (1988). "Robert 'Tiny' Maxwell" (PDF). College Football Historical Society. LA 84 Foundation. 1 (4): 1–3.

- Watterson, John (2001). "Tiny Maxwell and the Crisis of 1905: The Making of a Gridiron Myth" (PDF). College Football Historical Society. LA 84 Foundation: 54–57.

- "Tiny Maxwell Dies from Motor Injuries". New York Times. New York Times Publishing (July 1): 10. July 1, 1922. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Swarthmore College History