Tiwi Islands

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">Ratuati Irara ("two islands") | |

|---|---|

|

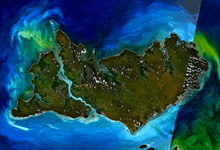

Landsat 7 imagery of the Tiwi Islands. | |

Tiwi Islands | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Arafura Sea |

| Coordinates | 11°36′S 130°49′E / 11.600°S 130.817°ECoordinates: 11°36′S 130°49′E / 11.600°S 130.817°E |

| Total islands | 11 |

| Major islands |

Melville Island Bathurst Island |

| Area | 8,320 km2 (3,210 sq mi) |

| Coastline | 1,016 km (631.3 mi) |

| Administration | |

|

Australia | |

| State or territory | Northern Territory |

| LGA | Tiwi Islands Shire |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,579 (August 2011) |

| Pop. density | 0.31 /km2 (0.8 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Tiwi people |

| Additional information | |

| Official website | http://www.tiwiislands.nt.gov.au/ |

The Tiwi Islands are part of the Northern Territory, Australia, 80 km to the north of Darwin where the Arafura Sea joins the Timor Sea. They comprise Melville Island, Bathurst Island, and nine smaller uninhabited islands, with a combined area of 8,320 square kilometres (3,212 sq mi).

Inhabited before European settlement by the Tiwi indigenous Australians, there are approximately 3,000 people on the islands.

The Tiwi Land Council is one of four land councils in the Northern Territory. It is a representative body with statutory authority under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 and has responsibilities under the Native Title Act 1993 and the Pastoral Land Act 1992.

Geography and population

The Tiwi Islands lie 80 km to the north of the Australian mainland in the Arafura Sea, and are part of the Northern Territory.[1] The island group consists of two large inhabited islands (Melville and Bathurst), and nine smaller uninhabited islands (Buchanan, Harris, Seagull, Karslake, Irritutu, Clift, Turiturina, Matingalia and Nodlaw).[2] Bathurst Island is the fifth-largest island of Australia and accessible by sea or air.[3] Melville Island is Australia's second largest island (after Tasmania).[4]

The main islands are separated by Apsley Strait, which connects Saint Asaph Bay in the north and Shoal Bay in the south, and is between 550 metres and 5 km wide, 62 km long. At the mouth of Shoal Bay is Buchanan Island, with an area of about 3 km2. A car ferry at the narrowest point provides a quick connection between the two islands.

They are inhabited by the Tiwi people, as they have been since before European settlement in Australia. The Tiwi are an Indigenous Australian people, culturally and linguistically distinct from those of Arnhem Land on the mainland just across the water. They number around 2,500.[5] In 2011, the total population of the islands was 2,579, of whom 87.9% were Aboriginal.[6] Most residents speak Tiwi as their first language and English as a second language.[7] Most of the population live in Wurrumiyanga (known as Nguiu until 2010) on Bathurst Island, and Pirlangimpi (also known as Garden Point) and Milikapiti (also known as Snake Bay) on Melville Island. Wurrumiyanga has a population of nearly 1500, the other two centres around 450 each.[8]

There are other smaller settlements, including Wurankuwu (Ranku) Community on western Bathurst Island.[9]

History

Indigenous Australians have occupied the Tiwi Islands for centuries, with creation stories suggesting they were present at least 7,000 years before present.[10]

Tiwi islanders are believed to have had contact with Macassan traders,[11] and the first historical record of contact between Indigenous islanders and western explorers was with the Dutch "under the command of Commander Maarten van Delft who took three ships, the Nieuw Holland, the Waijer, and the Vosschenbosch, into Shark Bay on Melville Island and landed on 30 April 1705".[10] There were other visits by explorers and navigators in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including by Dutchman Pieter Pieterszoon, Frenchman Nicholas Baudin and Briton Philip Parker King.[12]

The first European settlement on the Islands was at Fort Dundas, near present-day Pirlangimpi on Melville Island. Established in September 1824, this was the first British settlement in northern Australia, but owing in part to the hostility of the Indigenous population it lasted only five years, being abandoned in 1829.[12] As "the first attempted European and military settlement anywhere in northern Australia", the site is on Australia's Register of the National Estate.[13]

A Catholic mission was established by Francis Xavier Gsell in 1911,[11][14] and the islands were proclaimed an Aboriginal Reserve in 1912. A timber church built in the 1930s is a prominent landmark in Wurrumiyanga.[11] The Catholic mission had positive impacts, through access to education and welfare services, but also negative effects through the suppression of Aboriginal language and culture.[15]

Control of the islands was transferred to the Indigenous traditional owners through the Tiwi Aboriginal Land Trust, and the Tiwi Land Council that was founded in 1978.[10][16] The Tiwi Islands local government area was established in 2001, when the previous community government councils in the three main communities of Wurrumiyanga (Bathurst Island), Pirlangimpi and Milikapiti (Melville Island) were amalgamated with the Wurankuwu Aboriginal Corporation to form a single local government.[17] The Tiwi Islands Local Government was replaced in 2008 by the Tiwi Islands Shire Council as part of a Northern Territory-wide restructuring of local government.[18]

Politics and administration

The Tiwi Islands are part of the federal electorate of Lingiari,[19] for which the current member is Warren Snowdon.[20] The islands are within the Northern Territory electorate of Arafura. The current member for Arafura is Lawrence Costa, from the Labor Party.[21]

The administration of the islands is divided between the local Tiwi Islands Shire Council, and the Indigenous landholder representative organisation, the Tiwi Land Council. Representatives on the Shire Council are elected from four wards, and include 11 councillors.[5]

- Milikapiti Ward (northeast Melville Island, largest)

- Nguiu Ward (south Bathurst Island, Buchanan Island)

- Pirlangimpi Ward (west and southwest Melville Island)

- Wurankuwu Ward (north Bathurst Island)

In 2011–12, the operating budget of the Tiwi Islands Shire Council was A$26.4 million.[22] As of 2013, the elected Mayor of Tiwi Islands Shire Council is Lynette Jane De Santis.[23]

Culture

Indigenous art

The creation of Indigenous Australian art is an important part of Tiwi Island culture and its economy. There are three Indigenous art centres on the islands: Tiwi Design, Munupi Arts & Crafts, and Jilamara Arts and Craft,[24] and these collaborate through a cooperative venture, Tiwi Art.[25] Apart from Tiwi Art network there are two independent operations: fabric design, printing and clothing business Bima Wear,[26] operated by Indigenous women since 1969, and Ngaruwanajirri, also known as 'The Keeping Place'.

Tiwi artists who have held international exhibitions or whose works are held in major Australian collections include Donna Burak,[27] Jean Baptiste Apuatimi,[28] and Fiona Puruntatameri.[29]

A lot of wood carvings of birds are made by Tiwi people. Some of these are displayed in the Mission Heritage Gallery on Bathurst Island. The carvings represent various birds from Tiwi mythology, which have various meanings. Certain birds tell the Tiwi people about approaching monsoonal rains whilst others warn of impending cyclones. Others, depending on the totem of the people, alert the Tiwi people that someone has died in a particular clan. There are others that represent ancestral beings who were, according to mythology, changed into birds. Carved birds are sometimes at the top of pukumani poles, which are placed at sacred burial sites.

The Tiwi people also create many of their designs on fabric. The main method uses wax to resist dyeing similarly to Indonesian batik prints. Various fabrics are used ranging from sturdy, woven cotton to delicate silks, from which they create silk scarves.

The creation of their artwork is usually a social activity and consists of groups of people sitting together and talking whilst they work in a relaxed fashion. Often these grouping are segregated by gender.

Australian rules football

Australian rules football is the most popular sport on the Tiwi Islands, and was introduced in 1941 by missionaries John Pye and Andy Howley.[30] There has been a Tiwi Islands Football League competition since 1969.[31]

The Tiwi Islands Football League Grand Final is held in March each year and attracts up to 3,000 spectators. The Tiwi Australian Football League has 900 participants out of a community of about 2600, the highest football participation rate in Australia (35%).[32]

Tiwi footballers are renowned for exquisite "one touch" skills. Many of the players have a preference for playing barefoot. Many of the male players also play for the St Mary’s Football Club in Darwin, which was formed specifically to allow Tiwi soldiers in the 1950s to play in the Northern Territory Football League.

The Tiwi Bombers Football Club fielded a team in the Northern Territory Football League from the 2006/07 season.

Notable footballers from the Tiwi Islands to have played in the national VFL / AFL competition include Ronnie Burns,[33] Maurice Rioli,[34] Cyril Rioli,[34] Dean Rioli, Michael Long,[33] Malcolm Lynch, Austin Wonaeamirri,[35] David Kantilla[36] and Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti.

Maurice Rioli (1982) and Michael Long (1993) are both uncles of Cyril Rioli (2015), and all three have won the Norm Smith Medal for being adjudged the best player of an AFL Grand Final.

The Tiwi Islands Football Club was the subject of a series on ABC's Message Stick in 2009, called "In A League of Their Own".[37]

Cricket

As reported in The Weekend Australian in 2010, Australian cricketers led by Mathew Hayden raised $200,000 for cricket development in the Tiwi Islands. With former internationals Allan Border, Michael Kasprowicz and Andy Bichel, the match between Hayden XI and Border XI had a turnout of 1,000 people, nearly half the islands' population.[38]

Transport

A commercial flight operator, Fly Tiwi, connects both islands to each other and to Darwin. Formed as an association between Hardy Aviation and the Tiwi Land Council, Fly Tiwi has daily flights to all three communities on the islands.[39]

The Arafura Pearl ferry connects Wurrumiyanga and Darwin, and makes the two-hour trip each way on three days a week.[40]

In 2008, local government maintained 925 km of roads on the islands.[22]

Environment, conservation and land use

The islands' climatic and geographical extremity means that they have distinctive vegetation and special conservation values:

because of their isolation and because they have extremely high rainfall, the Tiwi Islands support many species not recorded elsewhere in the Northern Territory (or in the world), and some range-restricted species. The Tiwi Islands contain the Territory’s best-developed (tallest and with greatest basal area) eucalypt forests and an unusually high density and extent of rainforests.[3]

Climate

The Tiwi Islands have a tropical monsoonal climate, with 2000 mm of rainfall on northern Bathurst Island and 1200 to 1400 mm on eastern Melville Island.[41] The wet season from November to April brings the islands the highest rainfall in the Northern Territory.[42] The Tiwi people describe three distinct seasons: the dry (season of smoke), the buildup (high humidity and cicadas songs) and the wet (storms) The seasons frame the lifestyle of the Tiwi people, dictating the food sources available and their ceremonial activities.[43]

| Climate data for Milikapiti (Melville Island) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.2 (99) |

36.2 (97.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.3 (99.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.1 (97) |

36.3 (97.3) |

37.2 (99) |

37.2 (99) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.3 (99.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

32.9 (91.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.1 (88) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.6 (90.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.8 (74.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.8 (73) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.0 (68) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.8 (64) |

15.0 (59) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.2 (63) |

17.8 (64) |

21.1 (70) |

21.3 (70.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 298.5 (11.752) |

295.2 (11.622) |

317.8 (12.512) |

102.3 (4.028) |

67.4 (2.654) |

5.9 (0.232) |

0.9 (0.035) |

4.5 (0.177) |

5.9 (0.232) |

51.2 (2.016) |

121.9 (4.799) |

282.8 (11.134) |

1,554.3 (61.193) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2mm) | 17.8 | 16.2 | 17.1 | 8.1 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 10.3 | 14.6 | 94.6 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[44] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Cape Fourcroy (Bathurst Island) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.3 (93.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

35.0 (95) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

36.3 (97.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.8 (91) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.0 (77) |

25.5 (77.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.0 (68) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 343.4 (13.52) |

280.4 (11.039) |

220.5 (8.681) |

144.0 (5.669) |

31.1 (1.224) |

7.2 (0.283) |

0.3 (0.012) |

0.5 (0.02) |

11.0 (0.433) |

67.4 (2.654) |

119.6 (4.709) |

308.5 (12.146) |

1,533.9 (60.39) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2mm) | 19.2 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 11.1 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 16.3 | 103.6 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[45] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The islands have been isolated from the Australian mainland since the last ice age. They are covered mainly with eucalypt forest on a gently sloping lateritic plateau. The extensive open forest, open woodlands and riparian vegetation are dominated by Darwin Stringybarks, Woollybutts, and Cajuputs. There are small patches of rainforest occurring in association with perennial freshwater springs, and mangroves occupying the numerous inlets.[42]

There is a range of threatened and endemic species on the Tiwi Islands. Thirty-eight threatened species have been recorded, and a number of plants and invertebrates are found nowhere else, including eight plant species and some land snails and dragonflies.[46] Threatened mammals include Brush-tailed rabbit rats, northern brush-tailed phascogales, false water rats and Carpentarian dunnarts.[42] The islands host the world's largest breeding colony of crested terns and a large population of the vulnerable olive ridley turtle;[46] a sea turtle conservation program commenced on the islands in 2007.[46] The seas and estuaries around the islands are home to several species of shark and saltwater crocodiles.

Important Bird Area

The islands have been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because they support relatively high densities of red goshawks, partridge pigeons and bush stone-curlews, as well as up to 12,000 (over 1% of the world population) great knots. Other birds for which the Tiwi Island populations are globally significant include chestnut rails, beach stone-curlews northern rosellas, varied lorikeets, rainbow pittas, silver-crowned friarbirds, white-gaped, yellow-tinted and bar-breasted honeyeaters, canary white-eyes and masked finches.[47] The birds have a high level of endemism at the subspecific level; the Tiwi masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae melvillensis) is considered endangered and the Tiwi hooded robin (Melanodryas cucullata melvillensis) is at least endangered and may be extinct.[42]

Forestry and mining

Forest products are an important part of the Tiwi Islands economy, but the sector has had a chequered history. Forestry dates back to 1898, with plantations being trialled from the 1950s and 1960s.[48][49] A native softwood enterprise was established in the mid-1980s, as a partnership between the private sector and the Land Council; however by the mid-1990s, the Land Council was winding the venture down, noting that its investor partner had "various tax driven ambitions which are growingly incompatible with our own employment and sustainable production goals".[50] Despite the setback, it was still considered that forestry was likely to be crucial to the Tiwi economy,[51] and in 2001 the Land Council and Australian Plantations Group commenced a major expansion of Acacia mangium plantations to supply woodchips.[52] The operations of Australian Plantations Group (later named Sylvatech) were purchased by Great Southern Group in 2005.[53] In 2006, the operations were reported to be "the largest native-forest clearing project in northern Australia".[54] In September 2007 the Northern Territory Government investigated claims that the company had breached environmental laws,[55] with financial penalties being imposed by the Federal environment department in 2008.[54] Much of the cleared land is used for cattle or monoculture plantations, which the timber company has maintained are an important source of local jobs.[56] Great Southern Plantations collapsed in early 2009, and the Tiwi Land Council has been examining options for future management of the plantations.[57]

The islands have mineral sands on both Melville Island's north coast and the western coast of Bathurst Island.[51] In 2005, Matilda Minerals developed a proposal for mining on the islands, which was assessed and approved in 2006.[58] In 2007 sand mining produced the first shipments of zircon and rutile for export to China.[59] A 7,800 tonne shipment was made in June 2007,[60] with a further 5,000 tonnes shipped later that year.[59] Matilda Minerals planned to conduct mining for four years,[59] however in August 2008 its Tiwi operations were halted, and in October it was placed in administration.[61][62]

See also

References

- ↑ Bathurst Island | About Australia

- ↑ Morris, John (2003). "Continuing "assimilation"? A shifting identity for the Tiwi – 1919 to the present". University of Ballarat. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Sites of Conservation Significance: Tiwi Islands" (PDF). Northern Territory Department of Natural Resources, Environment, the Arts and Sport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Education:geoscience basics: islands". Geoscience Australia. 2009. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- 1 2 "Bushtel: Northern Territory: Northern Region: Tiwi Shire". Government of the Northern Territory. 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ↑ "Census QuickStats: Tiwi Islands". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- ↑ Barker, Anne (2003-09-26). "Tiwi Islands School Wins English Literacy Award". ABC Stateline. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Tiwi Islands Shire Council Business Plan 2008–2009" (PDF). Tiwi Islands Shire Council. July 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Wurankuwu Community Online Information Directory". Ranku Store. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- 1 2 3 "Tiwi Land Council: History". Tiwi Land Council. 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- 1 2 3 Squires, Nick (2005-07-16). "Aborigines' island life". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- 1 2 Forrest, Peter (1995). The Tiwi Meet the Dutch: The First European Contacts (PDF). Tiwi Land Council.

- ↑ "Fort Dundas, Pularumpi, NT, Australia (Place ID 18163)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. 1993-06-22. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ↑ J. Franklin, The missionary with 150 wives, Quadrant 56 (7/8) (July/Aug 2012), 30–32.

- ↑ "Foreign settlement". Tiwi Art. 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Tiwi Land Council. "Regional Profile" (PDF). Tiwi Islands Regional Natural Resource Management Strategy. Tiwi Land Council. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Tiwi Islands Local Government (July 2002). "Tiwi Islands Local Government, Submission to Inquiry into Local Government and Cost Shifting" (PDF). House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, Finance and Public Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Elliot McAdam (Minister for Local Government) (2007-08-22). "Local Government Changes Introduced". Archived from the original on 29 July 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Map of Commonwealth Electoral Division of Lingiari" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ↑ "The Hon Warren Snowdon MP". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- ↑ "Electorate of Arafura: Profile". Northern Territory Electoral Commission. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- 1 2 Northern Territory Department of Local Government and Housing (August 2008). "Local Government Regional Management Plan – Northern Region" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ↑ "Elected members". Tiwi Islands Shire Council. 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ "A Guide to Aboriginal Art and the Aboriginal Owned Art Centres of the Kimberley and Top End" (PDF). Association of Northern, Kimberley and Arnhem Aboriginal Artists. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Tiwi Art". Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Bima Wear". Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ↑ "ANKAAA biography: Donna Burak – Tiwi Region". Association of Northern, Kimberley and Arnhem Aboriginal Artists. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Tiwi Art – upcoming exhibitions". Tiwi Art. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Collection: Snapper". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Tiwi Islands Grand Final". Stateline. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-03-24. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "Tiwi Islands Football League: 1969 – 2008". 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "Even a cyclone can't stop the footy". The Sun-Herald. 2005-03-20. Retrieved 2006-05-14.

- 1 2 Roffey, Chelsea (21 May 2009). "The Tiwi effect". AFL BigPond. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- 1 2 McFarlane, Glenn (2008-08-31). "Maurice: Cyril may be best Rioli yet". Herald Sun. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Burgan, Matt (22 May 2008). "Q&A with Austin Wonaeamirri". Melbourne Football Club. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "St Mary's F.C. – David Kantilla". Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ "In A League of Their Own". 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ↑ The Buzz | Cricket Blogs | ESPN Cricinfo

- ↑ "About Fly Tiwi". Fly Tiwi. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- ↑ "Arafura Pearl timetable". Sea-cat ferries and charters. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ↑ "Tiwi Islands Regional Natural Resource Management Strategy – Tiwi Physical Profile" (PDF). Tiwi Land Council. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- 1 2 3 4 BirdLife International. (2011). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Tiwi Islands. Downloaded from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-10. on 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Archived 17 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "MILIKAPITI". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ "POINT FAWCETT". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Sea Turtle Conservation and Education on the Tiwi Islands" (PDF). Department of the Environment and Water Resources, Commonwealth of Australia. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "IBA: Tiwi Islands". Birdata. Birds Australia. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Tiwi Land Council (March 2009). "Tiwi Land Council Submission to the Inquiry into Mining and Forestry on the Tiwi Islands". Senate Environment, Communications and the Arts References Committee. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ CSIRO (March 2009). "CSIRO Submission to the Inquiry into Mining and Forestry on the Tiwi Islands". Senate Environment, Communications and the Arts References Committee. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ Tiwi Land Council (November 1996). Tiwi Islands Region Economic Development Strategy. Winnellie, NT: Tiwi Land Council.

- 1 2 Tiwi Land Council (2004). Tiwi Islands Regional Natural Resource Management Strategy. Winnellie, NT: Tiwi Land Council.

- ↑ Australian Plantation Group Pty Ltd; Tiwi Land Council (2001-03-30). Australian Plantation Group Pty Ltd/Forestry/Melville Island/NT/Hardwood Plantation: Invitation for public comment. Canberra: Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

- ↑ Great Southern Limited (2005). Annual Report 2005. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Marian (2008-10-16). "Forest firm told to pay $2m for damaging islands". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ "Woodchip plantation breached environmental conditions: report". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2007-09-16. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "Land clearing threatens Tiwi Islands". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Ltd. 2007-09-17. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "$80 million needed for Tiwi plantations: council". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2009-07-16. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Northern Territory Government Environmental Protection Agency Program (May 2006). Andranangoo Creek West and Lethbridge Bay West Mineral Sands Mining Project: Environmental Assessment Report and Recommendations (PDF). Darwin, NT: Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Matilda's first shipment waltzes away" (PDF). Astron Ltd. 2007-08-03. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ "Matilda sends first sands from Tiwi Islands". Lloyd's List Daily Commercial News. Informa Australia Pty Ltd. 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ "Matilda Minerals Limited". Ferrier Hodgson. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ Tasker, Sarah-Jane (2008-10-22). "Matilda Minerals in administration as China sale fails". The Australian. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiwi Islands. |

- Tiwi Land Council

- Tiwi Islands Shire Council

- Tiwi Creation Stories

-

Tiwi Islands travel guide from Wikivoyage

Tiwi Islands travel guide from Wikivoyage