Tower of St. Olav

| Tower of St. Olav | |

|---|---|

| Part of Vyborg Castle | |

|

Current state (2003) | |

|

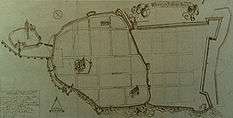

Vyborg Castle with Tower of St. Olav in the city map of Vyborg (1642) | |

| Coordinates | 60°42′56″N 28°43′43″E / 60.71556°N 28.72861°ECoordinates: 60°42′56″N 28°43′43″E / 60.71556°N 28.72861°E |

| Height | 48.6 metres (159 ft)[1] |

| Site information | |

| Owner | State museum Vyborg Castle |

| Open to the public | arter 1920s |

| Condition | Remains as a part of the state museum |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1293 |

| Built by | Torkel Knutsson, the Lord High Constable of Sweden |

| In use | on 1293 till 1964 |

The Tower of St. Olav is the one remaining tower of Vyborg Castle. It is a symbol and an architectural landmark of the city of Vyborg.

History

The fortress was conceived by Torkel Knutsson, the Lord High Constable of Sweden, who led in the 1290s a crusade to Karelia, the Third Finnish Crusade, which was actually aimed against the Russian state of Novgorod. He chose the location of the new fortress to command the Bay of Vyborg, which was a trading site already used by locals. From the bay, a river leads inland, ultimately connecting the place to several districts, lakes, and indirectly also to rivers going to Lake Ladoga.

1293 construction

By request of Torkel Knutsson the main fortress tower was constructed in 1293. According to the Russian military historians the first fortifications consisted of a rectangular donjon type tower and the closed perimeter of a defensive wall, which surrounded the tower. Russian archaeological excavations confirm this fact.[2]

The builders constructed the tower from huge boulders, according to traditions of the Italian fortification style then dominant in Europe. The tower was named for a legendary king of Norway, Olaf Sacred, who confirmed Christianity in Scandinavia and was later canonised.[3] The foundation of the tower is made of stone laid without application of a building solution; the tower walls are composed of stones cemented with use of a strong solution and revetted by boulders.[2]

The tower is rectangular (size is 15.5 х 15.6 meters), with walls 4.5 meters thick. The tower top has a crenelated wall on which a wooden gallery for defenders was erected. The castle cellar was used for storage of supplies and a prison, while the ground floor was used for living space. [4] The new fortress was repeatedly besieged by the armies of the Novgorod Republic, the most serious siege occurring in 1322. In this siege the most advanced artillery of the age was used: stone fougasse, including possibly the heavy arbalest.[2]

As a result of excavation, it has been discovered that wooden structures were once attached to the walls of the stone structure. Researchers have discovered traces burnt down in 14th century of a workshop processing bone and sheet bronze. They cannot, however, conclude with confidence whether or not a foundry works was present.[2]

In 1403 Vyborg received the official status of a city. Most likely at the beginning of 15th century the coast was connected with the lock by a bateau bridge named Fortress bridge.

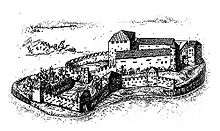

Before attaining the royal throne of Sweden, Karl Knutsson (Bonde) took residence in Vyborg in 1442 and began strengthening and expanding the castle. He constructed new premises and strengthened the castle with new walls and towers, arranging it on the model of the European cities of that time.[3] The tower of St. Olav received one more circle around it, connecting it with a group of buildings with which it was brought under a single roof in 1442–1448.[5]

Constructions of later time

In the middle of 16th century Swedish king Gustav Vasa reconstructed and strengthened a fortress for expansion of borders of the state on the east. In 1525 the German count Johan von Hoya, brother-in-law of Gustav Vasa, became deputy of the castle. Instead of taking actions to strengthen the castle as a military fortress he began to arrange balls and tournaments which demanded considerable expenses. King Gustav sent an army to conquer Vyborg and count Johan von Hoya fled to Lübeck.[6]

In 1555 when Gustav Vasa was preparing for his next war with Russia he visited Vyborg and spent some time living in the castle. He noted its shabby condition and mentioned in a letter «those lacks and errors» which he has seen in Finland.[6]

Russian: Во-первых, здесь, в замке никто не заботится о строительстве. Поэтому большинство домов и помещений стоят без крыш, все в таком упадке, что невозможно обеспечить оборону замка…

Translated: First, here, in the castle nobody cares of building. Therefore the majority of houses and premises stand without roofs, all in such decline that it is impossible to provide Castle defence…[6]

The king considered it a priority to carry out an urgent reconstruction of the defensive works both in the castle and in the city. Between 1556 and 1560 building was directed by deputy Klas Kristersson Horn.[6]

During this reconstruction Vyborg сastle took the general form that it has retained to this day, but Horn did not have time to finish the defensive works and Tower of St. Olav was finally reconstructed by his son, Eric XIV. In 1561–1564[5] the top part of the quadrangular tower was disassembled, and three floors re-erected in the form of an octangle. The tower was built of brick with a roof covered in lead specially brought from Stockholm.[3] Over an entry gate, by order of the king, were placed the arms «three crowns»; in the tower were placed artillery of large calibre; and in a cellar was installed a warehouse for kernels.[6]

During the Great Northern War Russian armies under Peter I took all the fortresses of Karelia and Ingria: in 1703–1704 – Nyenschantz, Jama, Koporye, Noteburg, and Ivangorod. Vyborg fell on June, 13th 1710.

The Medieval interiors of the castle remained up to the middle of 19th century, but the most part have been destroyed by fire. In 1834 lightning struck a flagstaff of the tower, sparking a fire that burnt down the wooden support beams; the tower was restored in 1844.[7]

From September, 7th [O.S. August, 26th] 1856 during celebrations on the occasion of opening of Saimaa Canal fireworks were arranged. These ignited the dome of the tower and from there the fire was thrown down on buildings standing nearby, consuming all of Vyborg Castle in flames. The fire consumed the wooden buildings abutting the Tower of St. Olav, and only the Commandant's house and buildings of the Forward courtyard escaped.[3] Tower restoration was undertaken by the engineer corps under Colonel E. Lezedov on the orders of Russian Military Office in 1891–1894. The tower gate was given a granite stoop, and the internal premises were built anew, including the addition of a metal ladder mounted to the top part of the tower leading up to a viewing platform.[3]

.jpg)

From May 1, 1913 through August 6, 1914 Nikolay Suhomlin supervised engineering and civil work on the fortress.[8] In the 1920s Finnish authorities again repaired the tower and partially opened it to the public, but it remained a military facility.[3]

Current state

Following the Second World War the territory on which the tower is built passed under the jurisdiction of Soviet Union. The castle lagged behind as a military facility and after 1964 it was transferred to the Vyborg state museum of local lore. In the castle, work continues on the maintenance and safety of the monument, and now Vyborg Castle is seen as a unique monument of West European military architecture that was shaped by developments from the 13th through 19th centuries.[3] Since 2000 the museum has been known as the State museum «Vyborg Castle».

It is now due for major restoration. Artem Novikov, chairman of the Russian Association of restorers, plans to begin restoration in 2010–2012.[9]

References

- ↑ Фортификации [Fortification] (in Russian). Noncommercial Welfare fund "the Renaissance of the Vyborg Castle". Retrieved 2009-09-07. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Tjulenev, V. A. (1995). Изучение старого Выборга [Studying of old Vyborg] (in Russian). Building history of Vyborg castle. Sketch.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The castle of Vyborg". Antiq.Info magazine. May 2007. Retrieved 2009-08-24. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Petrova, Larissa. Основание замка и первые десятилетия его существования [The basis of Castle and the first decades of its existence]. Vyborg (in Russian). Northern Fortresses. Retrieved 2009-09-04. External link in

|publisher=, |work=(help) - 1 2 M. I. Milchik (1998). The Swedish fortresses round Petersburg (in Russian). from the collection "Swedes on coast of Neva". Stockholm: Swedish Institute. pp. 26–33. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Petrova, Larissa. Замок в годы правления короля Густава Вазы и его сыновей [The castle in days of board of king Gustav Vazy and his sons]. Vyborg (in Russian). Northern Fortresses. Retrieved 2009-09-02. External link in

|publisher=, |work=(help) - ↑ Petrova, Larissa. В составе Российской империи [As a part of the Russian empire]. Vyborg (in Russian). Northern Fortresses. Retrieved 2009-09-07. External link in

|publisher=, |work=(help) - ↑ Выборгская крепость. Строители и защитники [Builders and defenders of a fortress] (in Russian). terijoki.spb.ru. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help); External link in|publisher=(help) - ↑ Башню св. Олафа и дворик в Выборгском замке планируют отреставрировать к 2012 году [Tower of St. Olaf and courtyard in the Vyborg Castle plan to restore by 2012]. Articles (in Russian). 47news.ru. 2009-08-12. Retrieved 2009-09-07. External link in

|publisher=(help)

External links

- Vyborg Castle at Northern Fortress

Выборгская крепость [Vyborg fortress] (in Russian). terijoki.spb.ru cite. Retrieved 2009-08-31. External link in |publisher= (help)