Trabecular cartilage

| Trabecular cartilage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Latin | trabecula cranii |

Trabecular cartilages (trabeculae cranii, sometimes simply trabeculae) are paired, rod-shaped cartilages, which develop in the head of the vertebrate embryo. They are the primordia of the anterior part of the cranial base, and are derived from the cranial neural crest cells.

Structure

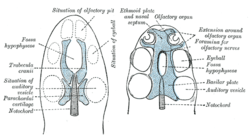

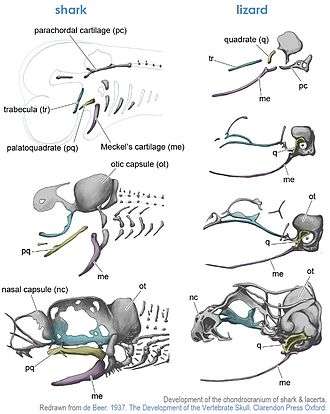

The trabecular cartilages generally appear as a paired, rod-shaped cartilages at the ventral side of the forebrain and lateral side of the adenohypophysis in the vertebrate embryo. During development, their anterior ends fuse and form the trabecula communis. Their posterior ends fuse with parachordal cartilages.

Development

Most skeletons are of mesodermal origin in vertebrates. Especially axial skeletal elements, such as the vertebrae, are derived from the paraxial mesoderm (e.g., somites), which is regulated by molecular signals from the notochord. Trabecular cartilages, however, originate from the neural crest, and since they are located anterior to the rostral tip of the notochord,[1] they cannot receive signals from the notochord. Due to these specialisations, and their essential role in cranial development, many comparative morphologists and embryologists have argued their developmental or evolutionary origins. Today’s general theory is that the trabecular cartilage is derived from the neural crest mesenchyme which fills anterior to the mandibular arch (premandibular domain).

Other animals

Lamprey

As clearly seen in the lamprey, Cyclostome also has a pair of cartilaginous rods in the embryonic head which is similar to the trabecular cartilages in jawed vertebrates. However, in 1916, Alexej Nikolajevich Sewertzoff pointed out that the cranial base of the lamprey is exclusively originated from the paraxial mesoderm. Then in 1948, Alf Johnels reported the detail of the skeletogenesis of the lamprey, and showed that the “trabecular cartilages” in lamprey appear just beside the notochord, in a similar position to the parachordal cartilages in jawed vertebrates.[2] Recent experimental studies also showed that the cartilages are derived from the head mesoderm.[3] Today, the “trabecular cartilages” in the Cyclostome is no longer considered to be the homologue of the trabecular in the jawed vertebrates: the (true) trabecular cartilages were firstly acquired in the Gnathostome lineage.

History

The trabecular cartilages were first described in the grass snake by Martin Heinrich Rathke at 1839.[4] In 1874, Thomas Henry Huxley pointed out that the trabecular cartilages are the modified viscerocranium: they assumed as the serial homologues of the branchial skeletons in the pharyngeal arches. The vertebrate jaw is generally thought to be the modification of the mandibular arch (1st pharyngeal arch). Since the trabecular cartilages appear anterior to the mandibular arch, if the trabecular cartilages are serial homologues of the pharyngeal arches, the ancestral vertebrates should possess more than one pharyngeal arch (so called “premandibular arches”) anterior to the mandibular arch. The existence of premandibular arch(es) has been accepted by many comparative embryologists and morphologists (e. g., Edwin Stephen Goodrich, Gavin de Beer). Moreover, Erik Stensio reported premandibular arches and the corresponding branchiomeric nerves by the reconstruction of the Osteostracans (e.g., Cephalaspis; recently this arch was reinterpreted as the mandibular arch) However, the existence of the premandibular arch(es) is rejected today, and the trabecular cartilages are not assumed to be one of the pharyngeal arches any more.

Footnotes

- ↑ their derivatives are called the prechordal cranium (Couly et al., 1993)

- ↑ Johnels AG (1948) On the development and morphology of the skeleton of the head of Petromyzon. Acta Zool 29: 139-279

- ↑ Kuratani S et al., (2004) Developmental fate of the mandibular mesoderm in the lamprey, Lethenteron japonicum: comparative morphology and development of the gnathostome jaw with special reference to the nature of trabecula cranii. J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.). 302B, 458-468

- ↑ Entwicklungsgeschichte der Natter. Konigsberg (1839)

References

- Couly GF, Coltey PM, Le Douarin NM. 1993. The triple origin of skull in higher vertebrates: A study in quail-chick chimeras. Development 117:409?429.

- de Beer GR. 1937. The Development of the Vertebrate Skull. Oxford University Press, London.