Trans-Karakoram Tract

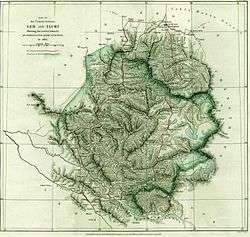

The Trans-Karakoram Tract (Hindi: शक्स्गम्, Shaksgam; Chinese: 喀喇昆仑走廊; pinyin: Kālǎkūnlún zǒuláng), also known as Shaksgam or the Shaksgam Tract, is an area of more than 9,900 km2 (3,822 sq mi) along both sides of the Shaksgam River and extending from the Karakoram to the Kunlun range. The tract is entirely administered by the People's Republic of China as a part of Kargilik County and Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County in the Kashgar Prefecture of Xinjiang Autonomous Region, but claimed by Pakistan until 1963.[1] It is claimed by India as part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Most of the tract is composed of the Shaksgam Valley[2] and was formerly administered as a part of Shigar, a valley in the Baltistan region. The Raja of Shigar controlled most of this land until 1971, when Pakistan abolished the Raja government system. A polo ground in Shaksgam was built by the Amacha Royal family of Shigar, and the Rajas of Shigar used to invite the Amirs of Yarkand to play polo there. Most of the names of the mountains, lakes, rivers and passes are in Balti/Ladakhi, suggesting that this land had been part of Baltistan/Ladakh region for a long time.

The tract is one of the most inhospitable areas of the world, with some of the highest mountains. Bounded by the Kun Lun Mountains in the north, and the Karakoram peaks to the south, including Broad Peak, K2 and Gasherbrum, on the southeast it is adjacent to the highest battlefield in the world on the Siachen Glacier region most of which is controlled by India.

History

Historically the people of Hunza cultivated and grazed areas to the north of the Karakoram, and the Mir of Hunza claimed those areas as part of Hunza's territories. Those areas included the Raskam Valley, north of the Shaksgam Valley.[3]

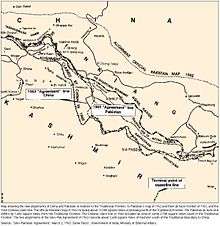

In 1889 the first expedition to the Shaksgam Valley by a European was undertaken by Francis Younghusband (who referred to the Shaksgam as the Oprang).[4] In March 1899 the British proposed, in a formal Note from Sir Claude MacDonald to China, a new boundary between China and British India. The Note proposed that China should relinquish its claims to suzerainty over Hunza, and in return Hunza should relinquish its claims to most of the Taghdumbash and Raskam districts. The Note proposed a border which broadly followed the main Karakoram crest dividing the watersheds of the Indus River and the Tarim River, but with a variation to pass through a Hunza post at Darwaza near the Shimshal Pass. The Chinese did not respond to the Note, and the British took that as acquiescence.[5] The Macdonald line was modified in 1905 to include in India a small area east of the Shimshal Pass, to put the border on the Oprang Jilga River and a stretch of the Shaksgam River.[6]

At the same time, in view of "The Great Game", Britain was concerned at the danger of Russian expansion as Qing dynasty China weakened and so adopted a policy of claiming a border north of the Shaksgam River. This followed a line proposed by Sir John Ardagh in a Memorandum of 1897.[7] That border included the Mir of Hunza's claim over the Raskam Valley. However, British administration never extended north of the Karakoram watershed.[8]

From 1899 until the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, the representation of the border on maps varied. In 1926 Kenneth Mason explored and surveyed the Shaksgam Valley 5,800 sq km[9] In 1927 the Government of British India abandoned any claim to the area north of the Macdonald line, but the decision did not find its way on to British maps.[10] By 1959, however, Chinese maps were published showing large areas west and south of the Macdonald line in China. That year, the Government of Pakistan announced its willingness to consult on the boundary question.[11]

From 1947 India claimed sovereignty over the entire area of the pre-1947 independent state of Jammu and Kashmir, and therefore maintained that Pakistan and China did not share a common border.

Sino-Pakistan Frontier Agreement

The Government of Pakistan had published an official map depicting the alignment of the northern Border of Kashmir in 1962 which depicted much of the Cis-Kuen Lun Tract as part of Kashmir and the alignment published by the Government of Pakistan predominantly was similar to and coincided with the portrayal of the northern Border of Kashmir in 1954 by the Times Atlas which had predominantly depicted the Cis-Kuen Lun Tract as a part of Kashmir under the caption ">Undefined Frontier area" [12] though at places, the official position of the Government of Pakistan deviated from the position of the Times Atlas, and the Government of Pakistan even depicted areas as part of Kashmir which were to the north of the border of Kashmir as published in 1954 by the Times Atlas! The northern border published by the Times Atlas in 1954 more or less followed the principle of watershed of the Kuen Lun range from the Taghdumbash Pamir to the Yangi Dawan pass north of Kulanaldi but east of the Yangi Dawan Pass, the border deviated from the principle of the watershed of the Kuen Lun range on the edge of the highlands of Kashmir and skipped from the Kuen Lun watershed rather than continuing on the Kilian, Sanju-la and Hindutash border Passes despite the statement that the “The eastern (Kuenlun) range forms the southern boundary of Khotan”,in the 1890 Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak [13] and is crossed by two other passes.The Gazetteer of Kashmír and Ladák compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch and first Published in 1890 gives a description and details of places inside Kashmir and thus includes a description of the Híñdutásh Pass in north eastern Kashmir in the Aksai Chin area in Kashmir . The aforesaid Gazetteer states in pages 520 and 364 that “The eastern (Kuenlun) range forms the southern boundary of Khotan”, “and is crossed by two passes, the Yangi or Elchi Diwan, .... and the Hindutak (i.e. Híñdutásh ) Díwán”. It describes Khotan as “ A province of the Chinese Empire lying to the north of the Eastern Kuenlun range, which here forms the boundary of Ladák[14]”. Thus the official position of the Government of Pakistan prior to 1963 was that the northern border of Pakistan was on the Kuen Lun range and the territory ceded by the Government of Pakistan was not just restricted to the Shaksgam Valley but extended to the Kuen Lun range. For an idea of the extent of the Trans-Karakoram Tract or the Cis-Kuen Lun Tract, a view the map (C) from the Joe Schwartzberg's Historical Atlas of South Asia at DSAL in Chicago with the caption, "The boundary of Kashmir with China as portrayed and proposed by Britain prior to 1947" would show that the geographical and territorial extent of the Trans-Karakoram Tract or the Cis-Kuen Lun Tract is more or less the territory enclosed between the northern most line and the innermost lines.

In 1959 the Pakistani government became concerned over Chinese maps that showed areas the Pakistanis considered their own as part of China. In 1961 Ayub Khan sent a formal note to China; there was no reply. It is thought that the Chinese might not have been motivated to negotiate with Pakistan because of Pakistan's relations with India.

After Pakistan voted to grant China a seat in the United Nations, the Chinese withdrew the disputed maps in January 1962, agreeing to enter border talks in March. Negotiations between the nations officially began on October 13, 1962 and resulted in an agreement signed on 2 March 1963 by foreign ministers Chen Yi of China and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan.

See also

References

- ↑ "China's Interests in Shaksgam Valley". Sharnoff's Global Views.

- ↑ "Pay attention to the sufferings of people of Gilgit and Baltistan".

- ↑ Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall

- ↑ Younghusband, Francis (1896). The Heart of a Continent. pp. 200ff.

- ↑ Woodman, Dorothy (1969). Himalayan Frontiers. Barrie & Rockcliff. pp. 74–75 and 366.

- ↑ Woodman (1969) pp.109 and 308

- ↑ Woodman (1969) p.107

- ↑ Woodman (1969) p.298, citing Alistair Lamb in the Australian Outlook, December 1964

- ↑ Exploration of the Shaksgam Valley and Aghil Ranges, by Kenneth Mason

- ↑ Woodman (1969), p. 107 and 298

- ↑ The Geographer. Office of the Geographer. Bureau of Intelligence and Research. Department of State, United States of America (November 15, 1968), China – Pakistan Boundary (PDF), International Boundary Study, 85, Florida State University College of Law

- ↑

- ↑ Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch. First Published in 1890

- ↑ The Gazetteer of Kashmír and Ladák compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch and first Published in 1890, at page 493

External links

Coordinates: 36°06′33″N 76°38′48″E / 36.10917°N 76.64667°E