Gestational trophoblastic disease

| Gestational trophoblastic disease | |

|---|---|

| |

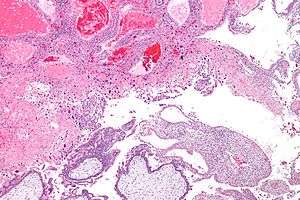

| Micrograph of intermediate trophoblast, decidua and a hydatidiform mole (bottom of image). H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| DiseasesDB | 2602 |

| MedlinePlus | 001496 |

| eMedicine | article/279116 |

| MeSH | D031901 |

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a term used for a group of pregnancy-related tumours. These tumours are rare, and they appear when cells in the womb start to proliferate uncontrollably. The cells that form gestational trophoblastic tumours are called trophoblasts and come from tissue that grows to form the placenta during pregnancy.

There are several different types of GTD. Hydatidiform moles are benign in most cases, but sometimes may develop into invasive moles, or, in rare cases, into choriocarcinoma, which is likely to spread quickly,[1][2] but which is very sensitive to chemotherapy, and has a very good prognosis. Gestational trophoblasts are of particular interest to cell biologists because, like cancer, these cells invade tissue (the uterus), but unlike cancer, they sometimes "know" when to stop.

GTD can simulate pregnancy, because the uterus may contain fetal tissue, albeit abnormal. This tissue may grow at the same rate as a normal pregnancy, and produces chorionic gonadotropin, a hormone which is measured to monitor fetal well-being.[3]

While GTD overwhelmingly affects women of child-bearing age, it may rarely occur in postmenopausal women.[4]

Commonly used synonyms

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) may also be called gestational trophoblastic tumour (GTT).

Hydatidiform mole (one type of GTD) may also be called molar pregnancy.

Persistent disease; persistent GTD: If there is any evidence of persistence of GTD, usually defined as persistent elevation of beta hCG (see «Diagnosis» below), the condition may also be referred to as gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN).[5]

Types

GTD is the common name for five closely related tumours (one benign tumour, and four malignant tumours):[6]

- The benign tumour

Here, first a fertilised egg implants into the uterus, but some cells around the fetus (the chorionic villi) do not develop properly. The pregnancy is not viable, and the normal pregnancy process turns into a benign tumour. There are two subtypes of hydatidiform mole: complete hydatidiform mole, and partial hydatidiform mole.

- The four malignant tumours

- Invasive mole

- Choriocarcinoma

- Placental site trophoblastic tumour

- Epithelioid trophoblastic tumour

All five closely related tumours develop in the placenta. All five tumours arise from trophoblastic cells. The trophoblast is the membrane that forms the wall of the blastocyst in the early development of the fetus. In a normal pregnancy, trophoblastic cells aid the implantation of the fertilised egg into the uterine wall. But in GTD, they develop into tumour cells.

Cause

Two main risk factors increase the likelihood for the development of GTD: 1) The woman being under 20 years of age, or over 35 years of age, and 2) previous GTD.[7][8][9]

Although molar pregnancies affect women of all ages, women under 16 years of age have a six times higher risk of developing a molar pregnancy than those aged 16–40 years, and women 50 years of age or older have a one in three chance of having a molar pregnancy.[10]

Being from Asia/of Asian ethnicity is an important risk factor.[11]

Hydatidiform moles are abnormal conceptions with excessive placental development. Conception takes place, but placental tissue grows very fast, rather than supporting the growth of a fetus.[12][13][14]

Complete hydatidiform moles have no fetal tissue and no maternal DNA, as a result of a maternal ovum with no functional DNA. Most commonly, a single spermatozoon duplicates and fertilises an empty ovum. Less commonly, two separate spermatozoa fertilise an empty ovum (dispermic fertilisation).

Partial hydatidiform moles have a fetus or fetal cells. They are triploid in origin, containing one set of maternal haploid genes and two sets of paternal haploid genes. They almost always occur following dispermic fertilisation of a normal ovum.

Malignant forms of GTD are very rare. About 50% of malignant forms of GTD develop from a hydatidiform mole.

Diagnosis

Cases of GTD can be diagnosed through routine tests given during pregnancy, such as blood tests and ultrasound, or through tests done after miscarriage or abortion.[15] Vaginal bleeding, enlarged uterus, pelvic pain or discomfort, and vomiting too much (hyperemesis) are the most common symptoms of GTD. But GTD also leads to elevated serum hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin hormone). Since pregnancy is by far the most common cause of elevated serum hCG, clinicians generally first suspect a pregnancy with a complication. However, in GTD, the beta subunit of hCG (beta hCG) is also always elevated. Therefore, if GTD is clinically suspected, serum beta hCG is also measured.

The initial clinical diagnosis of GTD should be confirmed histologically, which can be done after the evacuation of pregnancy (see «Treatment» below) in women with hydatidiform mole.[16] However, malignant GTD is highly vascular. If malignant GTD is suspected clinically, biopsy is contraindicated, because biopsy may cause life-threatening haemorrhage.

Women with persistent abnormal vaginal bleeding after any pregnancy, and women developing acute respiratory or neurological symptoms after any pregnancy, should also undergo hCG testing, because these may be signs of a hitherto undiagnosed GTD.

Treatment

Treatment is always necessary.

The treatment for hydatidiform mole consists of the evacuation of pregnancy.[17][18][19][20][21] Evacuation will lead to the relief of symptoms, and also prevent later complications. Suction curettage is the preferred method of evacuation. Hysterectomy is an alternative if no further pregnancies are wished for by the female patient. Hydatidiform mole also has successfully been treated with systemic (intravenous) methotrexate.[22]

The treatment for invasive mole or choriocarcinoma generally is the same. Both are usually treated with chemotherapy. Methotrexate and dactinomycin are among the chemotherapy drugs used in GTD.[23][24][25][26] Only a few women with GTD suffer from poor prognosis metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease. Their treatment usually includes chemotherapy. Radiotherapy can also be given to places where the cancer has spread, e.g. the brain.[27]

Women who undergo chemotherapy are advised not to conceive for one year after completion of treatment. These women also are likely to have an earlier menopause. It has been estimated by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists that the age at menopause for women who receive single agent chemotherapy is advanced by 1 year, and by 3 years for women who receive multi agent chemotherapy.

Follow up

Follow up is necessary in all women with gestational trophoblastic disease, because of the possibility of persistent disease, or because of the risk of developing malignant uterine invasion or malignant metastatic disease even after treatment in some women with certain risk factors.[28][29]

The use of a reliable contraception method is very important during the entire follow up period, as patients are strongly advised against pregnancy at that time. If a reliable contraception method is not used during the follow-up, it could be initially unclear to clinicians as to whether a rising hCG level is caused by the patient becoming pregnant again, or by the continued presence of GTD.

In women who have a malignant form of GTD, hCG concentrations stay the same (plateau) or they rise. Persistent elevation of serum hCG levels after a non molar pregnancy (i.e., normal pregnancy [term pregnancy], or preterm pregnancy, or ectopic pregnancy [pregnancy taking place in the wrong place, usually in the fallopian tube], or abortion) always indicate persistent GTD (very frequently due to choriocarcinoma or placental site trophoblastic tumour), but this is not common, because treatment mostly is successful.

In rare cases, a previous GTD may be reactivated after a subsequent pregnancy, even after several years. Therefore, the hCG tests should be performed also after any subsequent pregnancy in all women who had had a previous GTD (6 and 10 weeks after the end of any subsequent pregnancy).

Prognosis and staging

Women with a hydatidiform mole have an excellent prognosis. Women with a malignant form of GTD usually have a very good prognosis.

Choriocarcinoma, for example, is an uncommon, yet almost always curable cancer. Although choriocarcinoma is a highly malignant tumour and a life-threatening disease, it is very sensitive to chemotherapy. Virtually all women with non-metastatic disease are cured and retain their fertility; the prognosis is also very good for those with metastatic (spreading) cancer, in the early stages, but fertility may be lost. Hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) can also be offered[30] to patients > 40 years of age or those for whom sterilisation is not an obstacle. Only a few women with GTD have a poor prognosis, e.g. some forms of stage IV GTN. The FIGO staging system is used.[31] The risk can be estimated by scoring systems such as the Modified WHO Prognostic Scoring System, wherein scores between 1 and 4 from various parameters are summed together:[32]

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <40 | ≥40 | – | – |

| Antecedent pregnancy | mole | abortion | term | – |

| Interval months from index pregnancy | <4 | 4–6 | 7–12 | >12 |

| Pretreatment serum hCG (IU/L) | <103 | 103–104 | 104–105 | >105 |

| Largest tumor size (including uterus) | <3 | 3–4 cm | ≥5 cm | – |

| Site of metastases | lung | spleen, kidney | gastrointestinal | liver, brain |

| Number of metastases | – | 1–4 | 5–8 | >8 |

| Previous failed chemotherapy | – | – | single drug | ≥2 drugs |

In this scoring system, women with a score of 7 or greater are considered at high risk.

It is very important for malignant forms of GTD to be discovered in time. In Western countries, women with molar pregnancies are followed carefully; for instance, in the UK, all women who have had a molar pregnancy are registered at the National Trophoblastic Screening Centre.[33] There are efforts in this direction in the developing countries too, and there have been improvements in these countries in the early detection of choriocarcinoma, thereby significantly reducing the mortality rate also in developing countries.[34][35][36]

Becoming pregnant again

Most women with GTD can become pregnant again and can have children again. The risk of a further molar pregnancy is low. More than 98% of women who become pregnant following a molar pregnancy will not have a further hydatidiform mole or be at increased risk of complications.

In the past, it was seen as important not to get pregnant straight away after a GTD. Specialists recommended a waiting period of 6 months after the hCG levels become normal. Recently, this standpoint has been questioned. New medical data suggest that a significantly shorter waiting period after the hCG levels become normal is reasonable for approximately 97% of the patients with hydatidiform mole.[37]

Risk of a repeat GTD

The risk of a repeat GTD is approximately 1 in 100, compared with approximately 1 in 1000 risk in the general population. Especially women whose hCG levels remain significantly elevated are at risk of developing a repeat GTD.[38]

Persistent trophoblastic disease

The term «persistent trophoblastic disease» (PTD) is used when after treatment of a molar pregnancy, some molar tissue is left behind and again starts growing into a tumour. Although PTD can spread within the body like a malignant cancer, the overall cure rate is nearly 100%.

In the vast majority of patients, treatment of PTD consist of chemotherapy. Only about 10% of patients with PTD can be treated successfully with a second curettage.[39][40]

GTD coexisting with a normal fetus, also called "twin pregnancy"

In some very rare cases, a GTD can coexist with a normal fetus. This is called a "twin pregnancy". These cases should be managed only by experienced clinics, after extensive consultation with the patient. Because successful term delivery might be possible, the pregnancy should be allowed to proceed if the mother wishes, following appropriate counselling. The probability of achieving a healthy baby is approximately 40%, but there is a risk of complications, e.g. pulmonary embolism and pre-eclampsia. Compared with women who simply had a GTD in the past, there is no increased risk of developing persistent GTD after such a twin pregnancy.[41][42][43][44][45][46]

In few cases, a GTD had coexisted with a normal pregnancy, but this was discovered only incidentally after a normal birth.[47]

Epidemiology

Overall, GTD is a rare disease. Nevertheless, the incidence of GTD varies greatly between different parts of the world. The reported incidence of hydatidiform mole ranges from 23 to 1299 cases per 100,000 pregnancies. The incidence of the malignant forms of GTD is much lower, only about 10% of the incidence of hydatidiform mole.[48] The reported incidence of GTD from Europe and North America is significantly lower than the reported incidence of GTD from Asia and South America.[49][50][51][52] One proposed reason for this great geographical variation is differences in healthy diet in the different parts of the world (e.g., carotene deficiency).[53]

However, the incidence of rare diseases (such as GTD) is difficult to measure, because epidemiologic data on rare diseases is limited. Not all cases will be reported, and some cases will not be recognised. In addition, in GTD, this is especially difficult, because one would need to know all gestational events in the total population. Yet, it seems very likely that the estimated number of births that occur at home or outside of a hospital has been inflated in some reports.[54]

Related to this topic, but not GTD

- These are not GTD, and they are not tumours[55]

- Exaggerated placental site

- Placental site nodule

Both are composed of intermediate trophoblast, but their morphological features and clinical presentation can differ significantly.

Exaggerated placental site is a benign, non cancerous lesion with an increased number of implantation site intermediate trophoblastic cells that infiltrate the endometrium and the underlying myometrium. An exaggerated placental site may occur with normal pregnancy, or after an abortion. No specific treatment or follow up is necessary.

Placental site nodules are lesions of chorionic type intermediate trophoblast, usually small. 40 to 50% of placental site nodules are found in the cervix. They almost always are incidental findings after a surgical procedure. No specific treatment or follow up is necessary.

See also

References

- ↑ Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS (August 2010). "Gestational trophoblastic disease". Lancet. 376 (9742): 717–29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60280-2. PMID 20673583.

- ↑ Lurain JR (December 2010). "Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 203 (6): 531–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.073. PMID 20728069.

- ↑ Gestational trophoblastic disease: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Chiang JW, Berek JS. In: UpToDate [Textbook of Medicine]. Basow, DS (Ed). Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, and Wolters Kluwer Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2010.

- ↑ Chittenden B, Ahamed E, Maheshwari A (August 2009). "Choriocarcinoma in a postmenopausal woman". Obstet Gynecol. 114 (2 Pt 2): 462–5. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aa97e7. PMID 19622962.

- ↑ "Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (Green-top 38)" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guideline 2010. 2010-03-04.

- ↑ Gestational trophoblastic disease: Pathology. Kindelberger DW, Baergen RN. In: UpToDate [Textbook of Medicine]. Basow, DS (Ed). Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, and Wolters Kluwer Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2010.

- ↑ Kohorn EI (2007). "Dynamic staging and risk factor scoring for gestational trophoblastic disease". Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 17 (5): 1124–30. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00898.x. PMID 17386047.

- ↑ Kohorn EI (June 2002). "Negotiating a staging and risk factor scoring system for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. A progress report". J Reprod Med. 47 (6): 445–50. PMID 12092012.

- ↑ Kohorn EI (2001). "The new FIGO 2000 staging and risk factor scoring system for gestational trophoblastic disease: description and critical assessment". Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 11 (1): 73–7. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.011001073.x. PMID 11285037.

- ↑ "Gestational Trophoblastic Disease".

- ↑ Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

- ↑ Lipata F, Parkash V, Talmor M, et al. (April 2010). "Precise DNA genotyping diagnosis of hydatidiform mole". Obstet Gynecol. 115 (4): 784–94. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d489ec. PMID 20308840.

- ↑ Alifrangis C, Seckl MJ (December 2010). "Genetics of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: an update for the clinician". Future Oncol. 6 (12): 1915–23. doi:10.2217/fon.10.153. PMID 21142864.

- ↑ Azuma C, Saji F, Tokugawa Y, et al. (January 1991). "Application of gene amplification by polymerase chain reaction to genetic analysis of molar mitochondrial DNA: the detection of anuclear empty ovum as the cause of complete mole". Gynecol. Oncol. 40 (1): 29–33. doi:10.1016/0090-8258(91)90080-O. PMID 1671219.

- ↑ "Gestational Trophoblastic Tumors Treatment - National Cancer Institute". Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- ↑ Sebire NJ (2010). "Histopathological diagnosis of hydatidiform mole: contemporary features and clinical implications". Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 29 (1): 1–16. doi:10.3109/15513810903266138. PMID 20055560.

- ↑ Gerulath AH, Ehlen TG, Bessette P, Jolicoeur L, Savoie R (May 2002). "Gestational trophoblastic disease". J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 24 (5): 434–46. PMID 12196865.

- ↑ Lurain JR (January 2011). "Gestational trophoblastic disease II: classification and management of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.072. PMID 20739008.

- ↑ Sebire NJ, Seckl MJ (2008). "Gestational trophoblastic disease: current management of hydatidiform mole". BMJ. 337: a1193. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1193. PMID 18708429.

- ↑ Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP (April 2009). "Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy". N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (16): 1639–45. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0900696. PMID 19369669.

- ↑ Gestational trophoblastic disease: Management of hydatidiform mole. Garner EIO. In: UpToDate [Textbook of Medicine]. Basow, DS (Ed). Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, and Wolters Kluwer Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2010.

- ↑ De Vos M, Leunen M, Fontaine C, De Sutter P (2009). "Successful Primary Treatment of a Hydatidiform Mole with Methotrexate and EMA/CO". Case Report Med. 2009: 454161. doi:10.1155/2009/454161. PMC 2729468

. PMID 19707478.

. PMID 19707478. - ↑ Chalouhi GE, Golfier F, Soignon P, et al. (June 2009). "Methotrexate for 2000 FIGO low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia patients: efficacy and toxicity". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200 (6): 643.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.011. PMID 19393597.

- ↑ Abrão RA, de Andrade JM, Tiezzi DG, Marana HR, Candido dos Reis FJ, Clagnan WS (January 2008). "Treatment for low-risk gestational trophoblastic disease: comparison of single-agent methotrexate, dactinomycin and combination regimens". Gynecol. Oncol. 108 (1): 149–53. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.006. PMID 17931696.

- ↑ Malignant gestational trophoblastic disease: Staging and treatment. Garner EIO. In: UpToDate [Textbook of Medicine]. Basow, DS (Ed). Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, and Wolters Kluwer Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2010.

- ↑ Kang WD, Choi HS, Kim SM (June 2010). "Weekly methotrexate (50mg/m(2)) without dose escalation as a primary regimen for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". Gynecol. Oncol. 117 (3): 477–80. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.029. PMID 20347479.

- ↑ Lurain JR, Singh DK, Schink JC (2010). "Management of metastatic high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: FIGO stages II-IV: risk factor score > or = 7". J Reprod Med. 55 (5–6): 199–207. PMID 20626175.

- ↑ Kohorn EI (July 2009). "Long-term outcome of placental-site trophoblastic tumours". Lancet. 374 (9683): 6–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60791-1. PMID 19552947.

- ↑ Hoekstra AV, Lurain JR, Rademaker AW, Schink JC (August 2008). "Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: treatment outcomes". Obstet Gynecol. 112 (2 Pt 1): 251–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817f58ae. PMID 18669719.

- ↑ Lurain JR, Singh DK, Schink JC (2006). "Role of surgery in the management of high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". The Journal of reproductive medicine. 51 (10): 773–6. PMID 17086805.

- ↑ FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology (April 2009). "Current FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 105 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.015. PMID 19322933.

- 1 2 Stage Information for Gestational Trophoblastic Tumors and Neoplasia at The National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in turn citing: FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.: Current FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105 (1): 3-4, 2009

- ↑ "Molar Pregnancy".

- ↑ Izhar R, Aziz-un-Nisa (2003). "Prognosis of gestational choriocarcinoma at Khyber Teaching Hospital Peshawar". J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 15 (2): 45–8. PMID 14552249.

- ↑ Yang JJ, Xiang Y, Wan XR, Yang XY (August 2008). "Prognosis of malignant gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: 20 years of experience". J Reprod Med. 53 (8): 600–7. PMID 18773625.

- ↑ Lok CA, Ansink AC, Grootfaam D, van der Velden J, Verheijen RH, ten Kate-Booij MJ (November 2006). "Treatment and prognosis of post term choriocarcinoma in The Netherlands". Gynecol. Oncol. 103 (2): 698–702. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.011. PMID 16790263.

- ↑ Wolfberg AJ, Feltmate C, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS, Lieberman E (September 2004). "Low risk of relapse after achieving undetectable HCG levels in women with complete molar pregnancy". Obstet Gynecol. 104 (3): 551–4. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000136099.21216.45. PMID 15339768.

- ↑ Garrett LA, Garner EI, Feltmate CM, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS (July 2008). "Subsequent pregnancy outcomes in patients with molar pregnancy and persistent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". J Reprod Med. 53 (7): 481–6. PMID 18720922.

- ↑ van Trommel NE, Massuger LF, Verheijen RH, Sweep FC, Thomas CM (October 2005). "The curative effect of a second curettage in persistent trophoblastic disease: a retrospective cohort survey". Gynecol. Oncol. 99 (1): 6–13. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.032. PMID 16085294.

- ↑ Gillespie AM, Kumar S, Hancock BW (April 2000). "Treatment of persistent trophoblastic disease later than 6 months after diagnosis of molar pregnancy". Br. J. Cancer. 82 (8): 1393–5. doi:10.1054/bjoc.1999.1124. PMC 2363366

. PMID 10780516.

. PMID 10780516. - ↑ Lee SW, Kim MY, Chung JH, Yang JH, Lee YH, Chun YK (February 2010). "Clinical findings of multiple pregnancy with a complete hydatidiform mole and coexisting fetus". J Ultrasound Med. 29 (2): 271–80. PMID 20103799.

- ↑ Suri S, Davies M, Jauniaux E (2009). "Twin pregnancy presenting as a praevia complete hydatidiform mole and coexisting fetus complicated by a placental abscess". Fetal. Diagn. Ther. 26 (4): 181–4. doi:10.1159/000253272. PMID 19864876.

- ↑ Dolapcioglu K, Gungoren A, Hakverdi S, Hakverdi AU, Egilmez E (March 2009). "Twin pregnancy with a complete hydatidiform mole and co-existent live fetus: two case reports and review of the literature". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 279 (3): 431–6. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0737-x. PMID 18679699.

- ↑ Vandenhove M, Amant F, van Schoubroeck D, Cannie M, Dymarkowski S, Hanssens M (May 2008). "Complete hydatidiform mole with co-existing healthy fetus: a case report". J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 21 (5): 341–4. doi:10.1080/14767050801925156. PMID 18446663.

- ↑ True DK, Thomsett M, Liley H, et al. (September 2007). "Twin pregnancy with a coexisting hydatiform mole and liveborn infant: complicated by maternal hyperthyroidism and neonatal hypothyroidism". J Paediatr Child Health. 43 (9): 646–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01145.x. PMID 17688651.

- ↑ Behtash N, Behnamfar F, Hamedi B, Ramezanzadeh F (April 2009). "Term delivery following successful treatment of choriocarcinoma with brain metastases, a case report and review of literature". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 279 (4): 579–81. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0753-x. PMID 18726607.

- ↑ Ganapathi KA, Paczos T, George MD, Goodloe S, Balos LL, Chen F (September 2010). "Incidental finding of placental choriocarcinoma after an uncomplicated term pregnancy: a case report with review of the literature". Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 29 (5): 476–8. doi:10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181d81cc2. PMID 20736774.

- ↑ Altieri A, Franceschi S, Ferlay J, Smith J, La Vecchia C (November 2003). "Epidemiology and aetiology of gestational trophoblastic diseases". Lancet Oncol. 4 (11): 670–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01245-2. PMID 14602247.

- ↑ Savage P, Williams J, Wong SL, et al. (2010). "The demographics of molar pregnancies in England and Wales from 2000-2009". J Reprod Med. 55 (7–8): 341–5. PMID 20795349.

- ↑ Soares PD, Maestá I, Costa OL, Charry RC, Dias A, Rudge MV (2010). "Geographical distribution and demographic characteristics of gestational trophoblastic disease". J Reprod Med. 55 (7–8): 305–10. PMID 20795343.

- ↑ Chauhan A, Dave K, Desai A, Mankad M, Patel S, Dave P (2010). "High-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia at Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute: thirteen years of experience". J Reprod Med. 55 (7–8): 333–40. PMID 20795348.

- ↑ Kashanian M, Baradaran HR, Teimoori N (October 2009). "Risk factors for complete molar pregnancy: a study in Iran". J Reprod Med. 54 (10): 621–4. PMID 20677481.

- ↑ Berkowitz RS, Cramer DW, Bernstein MR, Cassells S, Driscoll SG, Goldstein DP (August 1985). "Risk factors for complete molar pregnancy from a case-control study". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 152 (8): 1016–20. PMID 4025447.

- ↑ Palmer JR (March 1994). "Advances in the epidemiology of gestational trophoblastic disease". J Reprod Med. 39 (3): 155–62. PMID 8035370.

- ↑ Shih IM, Seidman JD, Kurman RJ (June 1999). "Placental site nodule and characterization of distinctive types of intermediate trophoblast". Hum. Pathol. 30 (6): 687–94. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90095-3. PMID 10374778.

External links

- Molar Pregnancy

- MyMolarPregnancy.com Information about molar pregnancy and choriocarcinoma.

- Pathology of molar pregnancy

- EVERYTHING ABOUT MOLA, is the second highest treatment center in the world

- Clinically reviewed gestational trophoblastic tumour information for patients, from Cancer Research UK

- Cancer.Net: Gestational Trophoblastic Tumor