USS Constellation (1797)

USS Constellation by John W. Schmidt | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Constellation |

| Namesake: | The 15 stars in the contemporary United States national flag[1] |

| Ordered: | 27 March 1794[1] |

| Builder: | David Stodder[2] |

| Cost: | $314,212 |

| Launched: | 7 September 1797[2] |

| Nickname(s): | "Yankee Racehorse" |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1853[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | 38-Gun frigate[1] |

| Displacement: | 1,265 tons[1] |

| Length: | 164 ft (50 m) between perpendiculars[2] |

| Beam: | 41 ft (12 m)[2] |

| Depth of hold: | 13.5 ft (4.1 m)[2] |

| Decks: | Orlop, Berth, Gun, Spar |

| Propulsion: | Sail (three masts, ship rig) |

| Complement: | 340 officers and enlisted[2] |

| Armament: |

|

USS Constellation was a 38-gun frigate, one of the "Six Original Frigates" authorized for construction by the Naval Act of 1794. She was distinguished as the first U.S. Navy vessel to put to sea and the first U.S. Navy vessel to engage and defeat an enemy vessel. Constructed in 1797, she was modified several times in succeeding decades, and finally rebuilt beginning in 1853 as the sloop of war USS Constellation (1854).

Design and construction

American merchant vessels began to fall prey to Barbary Pirates, along the so-called "Barbary Coast" of North Africa, Morocco, Tunis (in future Tunisia), Tripoli (in future Libya), and most notably from Algiers (in future Algeria), in the Mediterranean Sea during the 1790s. Congress responded with the Naval Act of 1794.[3] The Act provided funds for the construction of six frigates to be built in six different East Coast ports; however, it included a clause stating that construction of the ships would cease if the United States agreed to peace terms with Algiers.[4][5] By the time of the conclusion in 1815, of the later War of 1812 with Great Britain, the United States had fought a series of three brief, but savage naval and amphibious wars.

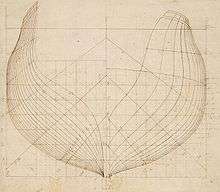

Joshua Humphreys' design was long on keel and narrow of beam (width) to allow the mounting of very heavy guns. The design incorporated a diagonal scantling (rib) scheme to limit hogging and included extremely heavy planking. This gave the hull greater strength than those of more lightly built frigates. Humphreys developed his design after realizing that the fledgling United States could not match for size the navies of the European states. He therefore designed his frigates to be able to overpower other frigates, but with the speed to escape from a "ship of the line" (equivalent to a modern-day "battleship").[6][7][8]

The United States Frigate Constellation was built under the direction of Colonel David Stodder at his naval shipyard on Harris Creek in Baltimore's Fell's Point maritime community, according to a design by Joshua Humphreys and launched on 7 September 1797, just as the United States entered the Quasi-War with the revolutionary French Republic. Harris Creek which flows into the Northwest Branch of the Patapsco River was later filled in to gain additional land for residential/industrial development and diverted underground to a subterranean storm drain and culvert in the early 19th century. It was situated east of Fell's Point and south of where modern-day Patterson Park, (near Highlandtown), and the community of Canton are currently located.

An earlier visitor to the Harris Creek naval shipyard of David Stodder, east of Baltimore Town in 1796, the Duke de la Rochefoucaule-Liancourt, saw the Constellation under construction and noted in his journal: "I thought her too much encumbered with wood-work within, but in other respects she is a fine vessel being built of those beautiful kinds of wood, the ever-green oak and cedar; she is pierced for 36 guns."[9]

Armament

The Naval Act of 1794 had specified 36-gun frigates; however, Constellation and her sister-ship Congress were re-rated to 38's because of their large dimensions, being 164 ft (50 m) in length and 41 ft (12 m) in width.[10][11][Note 1]

The "ratings" by number of guns were meant only as an approximation, as Constellation could and did often carry up to 48 guns.[14] U.S. Navy ships of this era had no permanent battery of guns such as modern Navy ships carry. The guns were designed to be completely portable and often were exchanged between ships as situations warranted. Each commanding officer outfitted armaments to his liking, taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel aboard, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, the armaments on ships changed often during their careers, and records of the changes were not generally kept.[15]

Quasi-War

Constellation vs. L'Insurgente

On 9 February 1799, under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun, Constellation fought and captured the frigate L'Insurgente of 36 guns, the fastest ship in the French Navy. The battle started about 18 miles (29 km) NE of the island of Nevis about midday when Constellation spotted L'Insurgente, which cracked on studding sails and attempted to run.[16] L'Insurgente had recently captured Retaliation, a schooner, in November 1798 and three weeks previous had been chased by the Constitution and had escaped. L’Insurgente's job was that of commerce raiding; she wanted nothing to do with another warship and tried to flee Constellation. Within an hour of hauling in chase Truxtun was close enough to make private signals to identify if the ship he was pursuing was British or not. With no answer, he proceeded to chase L'Insurgente down, clearing for action and beating to quarters. Truxtun made private signals for the US Navy and again received no answer.[17] Constellation crowded on all sail despite a rising squall that threatened to tear a sail or throw a spar.[18]

Reefing sail just long enough to weather the short squall, Constellation hardly paused but the same was not to be for L'Insurgente as her topmast snapped and slowed her to the onrushing Constellation.[18] Captain Barreaut ordered L'Insurgente to lay up and prepared to fight. Constellation was outfitted with 24 pounder guns that caused her to lean too much to lee due to topweight and thus had to surrender the weather gage to L'Insurgente. She was refitted with 18-pounder long guns in her next refit. L'Insurgente raised the French Tricolor and Captain Barreaut tried to ask for parley. Captain Truxtun refused to answer as his orders were to attack any French warship or privateer and answered when his last gun could be brought to bear.[19] American warships of this period fired for the hull as did the British and each of the 24 pounders had been double shotted. L'Insurgente fired as per her training at the Constellation's masts and rigging. Constellation's masts were saved when her sail was reduced taking pressure off the damaged mast.[19] L'Insurgente was devastated by Constellation's first broadside with many dead and others deserting their guns. L'Insurgente tried to board and slowed to close but this allowed Constellation to shoot ahead and crossed her bows for a bow rake with another broadside. Constellation crossed to windward and L'Insurgente turned to follow with both crews now exchanging port broadsides instead of starboard.[20] One of Constellation's 24 pounders smashed through the hull of L'Insurgente. L'Insurgente's 12 pounders were not equal to the same task against Constellation's hull. Captain Barreaut had been shown one of Constellation's 24 pound cannonballs and understood that he was in a completely unequal contest with sails down and nothing comparable to reply with many already dead and wounded. He struck colors— the first major victory by an American-designed and -built warship.[21]

Constellation vs. La Vengeance

Constellation sailed under Captain Thomas Truxtun from Saint Kitts on 30 January, and encountered the French frigate La Vengeance, of the La Résistance class (design by Pierre Degay, with 30 x 24-pounder guns and 20 x 12-pounder guns) during the night on 1 February. La Vengeance was out weighed by Constellation but had the heavier broadside, 559 lb (254 kg) to 372 lb (169 kg).[22] La Vengeance attempted to run and had to be chased down.[23] An hour after sunset Constellation came into hailing range and when La Vengeance was ordered to stand to and surrender, she answered with a broadside.[23] After an hour Constellation's foresails failed and had to be repaired; she then overtook La Vengeance and a running battle exchanging broadsides continued.[24] Twice the ships came close enough that boarders were called for on both ships, the second occasion was quite bloody as US Marines in the Constellation shot up the deck of La Vengeance leaving her deck covered in bodies of the dead and wounded, and forcing her boarding party to seek cover. A young Lieutenant standing next to Captain Pitot of the La Vengeance had his arm taken off at this time.[25] Constellation was victorious after a five-hour battle. La Vengeance was so holed in the hull and her rigging so cut up that she grounded outside the port of Curaçao rather than attempt to sail into port for fear of sinking. The French commander just managed to save his ship from capture and - upon returning to port - was so humiliated he later boasted that the American ship he had fought was a much larger and more powerful ship of the line. Despite a heavier broadside Captain Pitot of the La Vengeance accounted that she had fired 742 rounds in the engagement while Captain Truxtun of Constellation reported 1,229 rounds expended.[22] Constellation's rigging and spars were so damaged she dare not try to sail upwind and so went to port in Jamaica. Unable to complete a refit she limped home on a jury rig.[25] After the encounter, the Constellation's speed and power inspired the French to nickname her the "Yankee Racehorse."

First Barbary War

During the United States' preoccupation with France during the Quasi-War, troubles with the Barbary States were suppressed by the payment of tribute to ensure that American merchant ships were not harassed and seized.[26] In 1801 Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli, dissatisfied with the amount of tribute he was receiving in comparison to Algiers, demanded an immediate payment of $250,000.[27] In response, Thomas Jefferson sent a squadron of frigates to protect American merchant ships in the Mediterranean and pursue peace with the Barbary States.[28][29]

The first squadron, under the command of Richard Dale in President, was instructed to escort merchant ships through the Mediterranean and negotiate with leaders of the Barbary States.[28]

Sailing with the squadron of Commodore Richard Morris, and later, with that of Commodores Samuel Barron and John Rodgers, Constellation served in the blockade of Tripoli in May 1802. She cruised widely throughout the Mediterranean in 1804 to show the flag; evacuated in June 1805 a contingent of U.S.Marines, as well as diplomatic personages, from Derne at the conclusion of a fleet-shore operation against Tripoli; and took part in a squadron movement against Tunis that culminated in peace terms in August 1805. Constellation returned to the States in November 1805, mooring at Washington where she later was placed in ordinary until 1812.[1]

War of 1812

Constellation underwent repairs at Washington in 1812-13, and with the advent of war with England, commanded by Captain Charles Stewart, she was dispatched to Hampton Roads. In January 1813, shortly after her arrival she was effectively blockaded by a British squadron of line-of-battle ships and frigates. She kedged up toward Norfolk, and when the tide rose ran in and anchored between the forts; and a few days later dropped down to cover the forts which were being built at Craney Island. Here she was exposed to attacks from the British force still lying in Hampton Roads, and, fearing they would attempt to carry her by surprise, Captain Stewart made preparation for defense. She was anchored in the middle of the narrow channel, flanked by gun-boats, her lower ports closed, not a rope left hanging over the sides; the boarding nettings, boiled in half-made pitch till they were as hard as wire, were triced outboard toward the yardarms, and loaded with kentledge to fall on the attacking boats when the tricing lines were cut, while the carronades were loaded to the muzzle with musket balls, and depressed so as to sweep the water near the ship. Twice, a force of British, estimated by their foes to number 2,000 men, started off at night to take Constellation by surprise but on each occasion they were discovered and closely watched by her guard-boats, and they never ventured to make the attack.[1][30]

Second Barbary War

Soon after the United States declared war against Britain in 1812, Algiers took advantage of the United States' preoccupation with Britain and began intercepting American merchant ships in the Mediterranean.[31] On 2 March 1815, at the request of President James Madison, Congress declared war on Algiers. Work preparing two American squadrons promptly began—one at Boston under Commodore William Bainbridge, and one at New York under Commodore Steven Decatur.[32][33]

Constellation, attached to the Mediterranean Squadron under Commodore Stephen Decatur, sailed from New York on 20 May 1815 and joined in the capture of the Algerian frigate Mashuda on 17 June 1815. Treaties of peace were soon reached with Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. Constellation remained with the squadron under Commodores William Bainbridge, Isaac Chauncey, and John Shaw to enforce the accords, returning to Hampton Roads only in December 1817.[1]

Later career

From 12 November 1819 to 24 April 1820 Constellation served as flagship of Commodore Charles Morris on the Brazil Station, protecting American commerce against privateers and supporting the negotiation of trade agreements with South American nations. On 25 July 1820, she sailed for the first time to Pacific waters where she was attached to the Squadron of Commodore Charles Stewart. She remained thus employed for two years, protecting American shipping off the coast of Peru, an area where disquiet erupted into revolt against Spain.

In 1825, Constellation was chosen as flagship for Commodore Lewis Warrington and began duty with the West India Squadron to eradicate waning piracy operations in the Caribbean. During an outbreak of yellow fever at Key West, Florida, Warrington moved the squadron's home port to Pensacola, Florida where a permanent base was established. Other ships operating with Constellation during this period in the West Indies were John Adams, Hornet, Spark, Grampus, Shark, Fox and Decoy. Warrington returned to the United States with Constellation in 1826.[34][35]

In August 1829, she cruised to the Mediterranean to watch over American shipping and to collect indemnities from previous losses suffered by U.S. merchantmen. While en route to her station, she carried the American ministers to France and England to their posts of duty. Returning to the United States in November 1831, she underwent minor repairs and departed again for the Mediterranean in April 1832 where she remained until an outbreak of cholera forced her to sail for home in November 1834.

In October 1835, Constellation sailed for the Gulf of Mexico to assist in crushing the Seminole uprising. She landed shore parties to relieve the Army garrisons and sent her boats on amphibious expeditions. After the mission had been accomplished, she then cruised with the West India Squadron until 1838 serving part of this period in the capacity of flagship for Commodore Alexander Dallas.

The decade of the 1840s saw Constellation circumnavigate the globe. As flagship of Captain Kearny and the East India Squadron, her mission, as assigned in March 1841, was to safeguard American lives and property against loss in the Opium War, and further, to enable negotiation of commercial treaties. En route home in May 1843 she entered the Hawaiian Islands, helping to keep them from becoming a British protectorate, and thereafter she sailed homeward making calls at South American ports.[1]

Fate

In 1853 Constellation was struck and broken up for scrap at the Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth Virginia. At the same time, the keel was laid for what became known as the sloop of war USS Constellation (1854). By the 20th century, the 1854 version was widely believed (including by the U.S. Navy) to be the 1797 version rather than the 1854 rebuild. In the latter half of the 20th century, the city of Baltimore continued to promote the ship as the original, but some naval historians understood the ship to be an 1854 sloop of war rebuild of the original frigate, using a number of original parts. Commemorative copper coins were struck from parts of the USS Constellation, and have become collector's items.[36][37]

Notes

- ↑ Officially in congressional documents Constellation was a 36-gun frigate.[12] Chapelle states the Constellation and the Congress were re-rated to 38's during construction by Humphreys because of their large dimensions.[10]

Canney references Chapelle when rating Constellation a 38-gun frigate, but also questions "... exactly what Humphreys had in mind with rating these ships as 44- or 36-gun frigates when the number of ports certainly did not correspond to the rating and, in fact, the ships rarely carried their rated batteries, reflecting contemporary usage. That first U.S. Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert re-rated the Constellation and the Congress to 38's once he compared the dimensions of the two ships with the also recently completed USF Chesapeake, which had been reduced in size from a 44 to the extent that she was smaller.[11]

Other sources, such as Lardas & Bryan, use the official ratings and note, "The US Navy officially carried only three rates of frigate during the period 1794–1826: 44-gun, 36-gun, and 32-gun. The rating was independent of the size of the ship or the weight of its armament, but important in terms of crew size, pay, and money spent to support the ship."[13]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Constellation". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chapelle 1949, p. 536

- ↑ Allen (1909), pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Beach (1986), p. 29.

- ↑ An Act to provide a Naval Armament. 1 Stat. 350 (1794). Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ Toll (2006), pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Beach (1986), pp. 29–30, 33.

- ↑ Allen (1909), pp. 42–45.

- ↑ Francois Alexandre Frederic duc de La-Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Travels Through the United States of North-America, the Country of the Jroquois and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796 und 1797, Volume 2, R. Phillips, London, 1799, p.343

- 1 2 Chapelle (1949), p. 128.

- 1 2 Beach (1986), p. 32.

- ↑ Number of vessels in service, and estimates of repairing and fitting for service those in ordinary, including frigate Constellation, S. Doc. 91, U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, 12th Congress, 1st session, 1812.

- ↑ Lardas, Mark (2008). American Light and Medium Frigates 1794–1836. Oxford: Osprey. p. 31. ISBN 1-84603-266-0. OCLC 183265266.

- ↑ Roosevelt (1883), p. 53.

- ↑ Jennings, John (1966). Tattered Ensign The Story of America's Most Famous Fighting Frigate, U.S.S. Constitution. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. pp. 17–19. OCLC 1291484.

- ↑ Toll (2006), p. 114.

- ↑ Toll (2006), p. 115.

- 1 2 Toll (2006), p. 116.

- 1 2 Toll (2006), p. 117.

- ↑ Toll (2006), p. 118.

- ↑ Toll (2006), p. 119.

- 1 2 Toll (2006), p. 135.

- 1 2 Toll (2006), p. 132.

- ↑ Toll (2006), p. 133.

- 1 2 Toll (2006), p. 134.

- ↑ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Allen (1905), pp. 88, 90.

- 1 2 Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 228.

- ↑ Allen (1905), p. 92.

- ↑ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, p. 6.

- ↑ Allen (1905), p. 281.

- ↑ Wheeler (1969), pp. 167–171.

- ↑ "Warrington". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ↑ http://www.coinbooks.org/esylum_v14n27a09.html

- ↑ https://www.vcoins.com/en/stores/coins_to_medals/37/product/1797_us__frigate_constellation_commemorative_medal/311899/Default.aspx

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs. Boston, New York and Chicago: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2618279.

- —— (1909). Our Naval War With France. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1202325.

- Beach, Edward L. (1986). The United States Navy 200 Years. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-03-044711-2. OCLC 12104038.

- Canney, Donald L. (2001). Sailing warships of the US Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-990-5. OCLC 49323919.

- Chapelle, Howard Irving (1949). The History of the American Sailing Navy; the Ships and Their Development. New York: Norton. OCLC 1471717.

- Cooper, James Fenimore (1856). History of the Navy of the United States of America. New York: Stringer & Townsend. OCLC 197401914.

- Hill, Frederic Stanhope (1905). Twenty-Six Historic Ships. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 1667284.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton; Smith, Roy Campbell (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. 1 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

- —— (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. 2 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

- Morris, Charles (1880). Soley, J. R., ed. "The Autobiography of Commodore Charles Morris U.S.N.". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. VI (12): 111–219. ISSN 0041-798X. OCLC 2496995.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1883) [1882]. The Naval War of 1812 (3rd ed.). New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. OCLC 133902576.

- Toll, Ian W (2006). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the US Navy. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05847-5. OCLC 70291925.

- Wegner, Dana M.; Ratliff, Colan D.; Lynaugh, Kevin (September 1991). "Fouled Anchors: The Constellation Question Answered" (PDF). Bethesda: David Taylor Research Center. OCLC 444899959. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- Wheeler, Richard (1969). In Pirate Waters. New York: Crowell. OCLC 6144.