Unconscious mind

The unconscious mind (or the unconscious) consists of the processes in the mind which occur automatically and are not available to introspection, and include thought processes, memories, interests, and motivations.[1]

Even though these processes exist well under the surface of conscious awareness they are theorized to exert an impact on behavior. The term was coined by the 18th-century German Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling and later introduced into English by the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[2][3]

Empirical evidence suggests that unconscious phenomena include repressed feelings, automatic skills, subliminal perceptions, thoughts, habits, and automatic reactions,[1] and possibly also complexes; hidden phobias and desires.

The concept was popularized by the Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. In psychoanalytic theory, unconscious processes are understood to be directly represented in dreams, as well as in slips of the tongue and jokes.

Thus the unconscious mind can be seen as the source of dreams and automatic thoughts (those that appear without any apparent cause), the repository of forgotten memories (that may still be accessible to consciousness at some later time), and the locus of implicit knowledge (the things that we have learned so well that we do them without thinking).

It has been argued that consciousness is influenced by other parts of the mind. These include unconsciousness as a personal habit, being unaware, and intuition. Phenomena related to semi-consciousness include awakening, implicit memory, subliminal messages, trances, hypnagogia, and hypnosis. While sleep, sleepwalking, dreaming, delirium, and comas may signal the presence of unconscious processes, these processes are seen as symptoms rather than the unconscious mind itself.

Some critics have doubted the existence of the unconscious.[4][5][6]

Historical overview

The term "unconscious" (German: Unbewusste) was coined by the 18th-century German Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling (in his System of Transcendental Idealism, ch. 6, § 3) and later introduced into English by the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge (in his Biographia Literaria).[2][3] Some rare earlier instances of the term "unconsciousness" (Unbewußtseyn) can be found in the work of the 18th-century German physician and philosopher Ernst Platner.[7][8]

Influences on thinking that originate from outside of an individual's consciousness were reflected in the ancient ideas of temptation, divine inspiration, and the predominant role of the gods in affecting motives and actions. The idea of internalised unconscious processes in the mind was also instigated in antiquity and has been explored across a wide variety of cultures. Unconscious aspects of mentality were referred to between 2500 and 600 BC in the Hindu texts known as the Vedas, found today in Ayurvedic medicine.[9][10][11]

Paracelsus is credited as the first to make mention of an unconscious aspect of cognition in his work Von den Krankheiten (translates as "About illnesses", 1567), and his clinical methodology created a cogent system that is regarded by some as the beginning of modern scientific psychology.[12] William Shakespeare explored the role of the unconscious[13] in many of his plays, without naming it as such.[14][15][16] In addition, Western philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer,[17][18] Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Søren Kierkegaard, and Friedrich Nietzsche[19] used the word unconscious.

In 1880, Edmond Colsenet supports at the Sorbonne, a philosophy thesis on the unconscious.[20] Elie Rabier and Alfred Fouillee perform syntheses of the unconscious "at a time when Freud was not interested in the concept".[21]

Psychology

Psychologist Jacques Van Rillaer points out that, "the unconscious was not discovered by Freud. In 1890, when psychoanalysis was still unheard of, William James, in his monumental treatise on psychology (The Principles of Psychology), examined the way Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Janet, Binet and others had used the term 'unconscious' and 'subconscious'".[22] Historian of psychology Mark Altschule observes that, "It is difficult—or perhaps impossible—to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance."[23]

Freud's view

Sigmund Freud and his followers developed an account of the unconscious mind. It plays an important role in psychoanalysis.

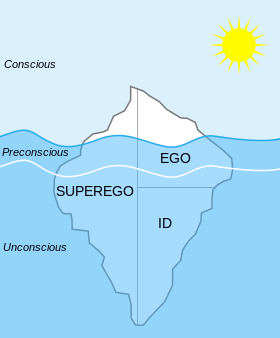

Freud divided the mind into the conscious mind (or the ego) and the unconscious mind. Later was then further divided into the id (or instincts and drive) and the superego (or conscience). In this theory, the unconscious refers to the mental processes of which individuals make themselves unaware.[24] Freud proposed a vertical and hierarchical architecture of human consciousness: the conscious mind, the preconscious, and the unconscious mind—each lying beneath the other. He believed that significant psychic events take place "below the surface" in the unconscious mind,[25] like hidden messages from the unconscious. He interpreted such events as having both symbolic and actual significance.

In psychoanalytic terms, the unconscious does not include all that is not conscious, but rather what is actively repressed from conscious thought or what a person is averse to knowing consciously. Freud viewed the unconscious as a repository for socially unacceptable ideas, wishes or desires, traumatic memories, and painful emotions put out of mind by the mechanism of psychological repression. However, the contents did not necessarily have to be solely negative. In the psychoanalytic view, the unconscious is a force that can only be recognized by its effects—it expresses itself in the symptom. In a sense, this view places the conscious self as an adversary to its unconscious, warring to keep the unconscious hidden. Unconscious thoughts are not directly accessible to ordinary introspection, but are supposed to be capable of being "tapped" and "interpreted" by special methods and techniques such as meditation, free association (a method largely introduced by Freud), dream analysis, and verbal slips (commonly known as a Freudian slip), examined and conducted during psychoanalysis. Seeing as these unconscious thoughts are normally cryptic, psychoanalysts are considered experts in interpreting their messages.

Freud based his concept of the unconscious on a variety of observations. For example, he considered "slips of the tongue" to be related to the unconscious in that they often appeared to show a person's true feelings on a subject. For example, "I decided to take a summer curse". This example shows a slip of the word "course" where the speaker accidentally used the word curse which would show that they have negative feelings about having to do this. Freud noticed that also his patient's dreams expressed important feelings they were unaware of. After these observations, he came to the conclusion that psychological disturbances are largely caused by personal conflicts existing at the unconscious level. His psychoanalytic theory acts to explain personality, motivation and mental disorders by focusing on unconscious determinants of behavior.[26]

Freud later used his notion of the unconscious in order to explain certain kinds of neurotic behavior.[27] The theory of the unconscious was substantially transformed by later psychiatrists, among them Carl Jung and Jacques Lacan.

In his 1932/1933 conferences, Freud "proposes to abandon the notion of the unconscious that ambiguous judge".[28]

Jung's view

Carl Gustav Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, developed the concept further. He agreed with Freud that the unconscious is a determinant of personality, but he proposed that the unconscious be divided into two layers: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious is a reservoir of material that was once conscious but has been forgotten or suppressed, much like Freud's notion. The collective unconscious, however, is the deepest level of the psyche, containing the accumulation of inherited psychic structures and archetypal experiences. Archetypes are not memories but images with universal meanings that are apparent in the culture's use of symbols. The collective unconscious is therefore said to be inherited and contain material of an entire species rather than of an individual.[29] Every person shares the collective unconscious with the entire human race, as Jung puts it: [the] "whole spiritual heritage of mankind's evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual".[30]

In addition to the structure of the unconscious, Jung differed from Freud in that he did not believe that sexuality was at the base of all unconscious thoughts.[31]

Controversy

The notion that the unconscious mind exists at all has been disputed.

Franz Brentano rejected the concept of the unconscious in his 1874 book Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, although his rejection followed largely from his definitions of consciousness and unconsciousness.[32]

Jean-Paul Sartre offers a critique of Freud's theory of the unconscious in Being and Nothingness, based on the claim that consciousness is essentially self-conscious. Sartre also argues that Freud's theory of repression is internally flawed. Philosopher Thomas Baldwin argues that Sartre's argument is based on a misunderstanding of Freud.[4]

Erich Fromm contends that, "The term 'the unconscious' is actually a mystification (even though one might use it for reasons of convenience, as I am guilty of doing in these pages). There is no such thing as the unconscious; there are only experiences of which we are aware, and others of which we are not aware, that is, of which we are unconscious. If I hate a man because I am afraid of him, and if I am aware of my hate but not of my fear, we may say that my hate is conscious and that my fear is unconscious; still my fear does not lie in that mysterious place: 'the' unconscious."[33]

John Searle has offered a critique of the Freudian unconscious. He argues that the Freudian cases of shallow, consciously held mental states would be best characterized as 'repressed consciousness,' while the idea of more deeply unconscious mental states is more problematic. He contends that the very notion of a collection of "thoughts" that exist in a privileged region of the mind such that they are in principle never accessible to conscious awareness, is incoherent. This is not to imply that there are not "nonconscious" processes that form the basis of much of conscious life. Rather, Searle simply claims that to posit the existence of something that is like a "thought" in every way except for the fact that no one can ever be aware of it (can never, indeed, "think" it) is an incoherent concept. To speak of "something" as a "thought" either implies that it is being thought by a thinker or that it could be thought by a thinker. Processes that are not causally related to the phenomenon called thinking are more appropriately called the nonconscious processes of the brain.[34]

Other critics of the Freudian unconscious include David Stannard,[5] Richard Webster,[6] Ethan Watters,[35] Richard Ofshe,[35] and Eric Thomas Weber.[36]

David Holmes[37] examined sixty years of research about the Freudian concept of "repression", and concluded that there is no positive evidence for this concept. Given the lack of evidence for many Freudian hypotheses, some scientific researchers proposed the existence of unconscious mechanisms that are very different from the Freudian ones. They speak of a "cognitive unconscious" (John Kihlstrom),[38][39] an "adaptive unconscious" (Timothy Wilson),[40] or a "dumb unconscious" (Loftus & Klinger),[41] which executes automatic processes but lacks the complex mechanisms of repression and symbolic return of the repressed.

In modern cognitive psychology, many researchers have sought to strip the notion of the unconscious from its Freudian heritage, and alternative terms such as "implicit" or "automatic" have come into currency. These traditions emphasize the degree to which cognitive processing happens outside the scope of cognitive awareness, and show that things we are unaware of can nonetheless influence other cognitive processes as well as behavior.[42][43][44][45][46] Active research traditions related to the unconscious include implicit memory (see priming, implicit attitudes), and nonconscious acquisition of knowledge (see Lewicki, see also the section on cognitive perspective, below).

Dreams

Freud

In terms of the unconscious, the purpose of dreams, as stated by Freud, is to fulfill repressed wishes through the process of dreaming, since they cannot be fulfilled in real life. For example, if someone was to rob a store and feel guilty about it, they might dream about a scenario in which their actions were justified and renders them blameless. Freud asserted that the wish-fulfilling aspect of the dream may be disguised due to the difficulty in distinguishing between manifest content and latent content. The manifest content consists of the plot of a dream at the surface level. The latent content refers to the hidden or disguised meaning of the events in the plot. The latent content of the dream is what supports the idea of wish fulfillment. It represents the intimate information in the dreamer's current issues and childhood conflict.[47]

Opposing theories

In response to Freud's theory on dreams, other psychologists have come up with theories to counter his argument. Theorist Rosalind Cartwright proposed that dreams provide people with the opportunity to act out and work through everyday problems and emotional issues in a non-real setting with no consequences. According to her cognitive problem solving view, a large amount of continuity exists between our waking thought and the thoughts that exist in dreams. Proponents of this view believe that dreams allow participation in creative thinking and alternate ways to handle situations when dealing with personal issues because dreams are not restrained by logic or realism.[47]

In addition to this, Allan Hobson and colleagues came up with the activation-synthesis hypothesis which proposes that dreams are simply the side effects of the neural activity in the brain that produces beta brain waves during REM sleep that are associated with wakefulness. According to this hypothesis, neurons fire periodically during sleep in the lower brain levels and thus send random signals to the cortex. The cortex then synthesizes a dream in reaction to these signals in order to try to make sense of why the brain is sending them. However, the hypothesis does not state that dreams are meaningless, it just downplays the role that emotional factors play in determining dreams.[47]

Contemporary cognitive psychology

Research

While, historically, the psychoanalytic research tradition was the first to focus on the phenomenon of unconscious mental activity, there is an extensive body of conclusive research and knowledge in contemporary cognitive psychology devoted to the mental activity that is not mediated by conscious awareness.

Most of that (cognitive) research on unconscious processes has been done in the mainstream, academic tradition of the information processing paradigm. As opposed to the psychoanalytic tradition, driven by the relatively speculative (in the sense of being hard to empirically verify) theoretical concepts such as the Oedipus complex or Electra complex, the cognitive tradition of research on unconscious processes is based on relatively few theoretical assumptions and is very empirically oriented (i.e., it is mostly data driven). Cognitive research has revealed that automatically, and clearly outside of conscious awareness, individuals register and acquire more information than what they can experience through their conscious thoughts. (See Augusto, 2010, for a recent comprehensive survey.)[48]

Unconscious processing of information about frequency

For example, an extensive line of research conducted by Hasher and Zacks[49] has demonstrated that individuals register information about the frequency of events automatically (i.e., outside of conscious awareness and without engaging conscious information processing resources). Moreover, perceivers do this unintentionally, truly "automatically," regardless of the instructions they receive, and regardless of the information processing goals they have. Interestingly, the ability to unconsciously and relatively accurately tally the frequency of events appears to have little or no relation to the individual's age,[50] education, intelligence, or personality, thus it may represent one of the fundamental building blocks of human orientation in the environment and possibly the acquisition of procedural knowledge and experience, in general.

See also

- Adaptive unconscious

- Consciousness

- Ernst Platner

- Introspection illusion

- List of thought processes

- Mind's eye

- Minimally conscious state

- Neuroscience of free will

- Philosophy of mind

- Preconscious

- Subconscious

- Transpersonal psychology

- Unconscious cognition

- Unconscious communication

- Instinct

- Books

- Psyche (1846)

- The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869)

Notes

- 1 2 Westen, Drew (1999). "The Scientific Status of Unconscious Processes: Is Freud Really Dead?". Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 47 (4): 1061–1106. doi:10.1177/000306519904700404. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- 1 2 Bynum; Browne; Porter (1981). The Macmillan Dictionary of the History of Science. London. p. 292.

- 1 2 Christopher John Murray, Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760-1850 (Taylor & Francis, 2004: ISBN 1-57958-422-5), pp. 1001–02.

- 1 2 Thomas Baldwin (1995). Ted Honderich, ed. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 792. ISBN 0-19-866132-0.

- 1 2 See "The Problem of Logic", Chapter 3 of Shrinking History: On Freud and the Failure of Psychohistory, published by Oxford University Press, 1980

- 1 2 See "Exploring the Unconscious: Self-Analysis and Oedipus", Chapter 11 of Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis, published by The Orwell Press, 2005

- ↑ Ernst Platner, Philosophische Aphorismen nebst einigen Anleitungen zur philosophischen Geschichte, Vol. 1 (Leipzig: Schwickertscher Verlag, 1793 [1776]), p. 86.

- ↑ Angus Nicholls and Martin Liebscher, Thinking the Unconscious: Nineteenth-Century German Thought (2010), Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ Alexander, C. N. 1990. Growth of Higher Stages of Consciousness: Maharishi's Vedic Psychology of Human Development. C. N. Alexander and E.J. Langer (eds.). Higher Stages of Human Development. Perspectives on Human Growth. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Meyer-Dinkgräfe, D. (1996). Consciousness and the Actor. A Reassessment of Western and Indian Approaches to the Actor's Emotional Involvement from the Perspective of Vedic Psychology. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-3180-X.

- ↑ Haney, W.S. II. "Unity in Vedic aesthetics: the self-interac, the known, and the process of knowing". Analecta Husserliana and Western Psychology: A comparison' 1934.

- ↑ Harms, Ernest., Origins of Modern Psychiatry, Thomas 1967 ASIN: B000NR852U, p. 20

- ↑ The Design Within: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Shakespeare: Edited by M. D. Faber. New York: Science House. 1970 An anthology of 33 papers on Shakespearean plays by psychoanalysts and literary critics whose work has been influenced by psychoanalysis

- ↑ Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel "Hamlet's Procrastination: A Parallel to the Bhagavad-Gita, in Hamlet East West, edited by. Marta Gibinska and Jerzy Limon. Gdansk: Theatrum Gedanese Foundation, 1998e, pp. 187-195

- ↑ Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel 'Consciousness and the Actor: A Reassessment of Western and Indian Approaches to the Actor's Emotional Involvement from the Perspective of Vedic Psychology.' Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1996a. (Series 30: Theatre, Film and Television, Vol. 67)

- ↑ Yarrow, Ralph (July–December 1997). "Identity and Consciousness East and West: the case of Russell Hoban". Journal of Literature & Aesthetics. 5 (2): 19–26.

- ↑ Ellenberger, H. (1970) The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry New York: Basic Books, p. 542

- ↑ Young, Christopher and Brook, Andrew (1994) Schopenhauer and Freud quotation:

Ellenberger, in his classic 1970 history of dynamic psychology. He remarks on Schopenhauer's psychological doctrines several times, crediting him for example with recognizing parapraxes, and urges that Schopenhauer "was definitely among the ancestors of modern dynamic psychiatry." (1970, p. 205). He also cites with approval Foerster's interesting claim that "no one should deal with psychoanalysis before having thoroughly studied Schopenhauer." (1970, p. 542). In general, he views Schopenhauer as the first and most important of the many nineteenth-century philosophers of the unconscious, and concludes that "there cannot be the slightest doubt that Freud's thought echoes theirs." (1970, p. 542).

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, preface to the second edition of "The Gay science" 1886

- ↑ "Un débat sur l'inconscient avant Freud: la réception de Eduard von Hartmann chez les psychologues et philosophes français". de Serge Nicolas et Laurent Fedi, L'Harmattan, 2008, p.8

- ↑ "Un débat sur l'inconscient avant Freud: la réception de Eduard von Hartmann chez les psychologues et philosophes français". de Serge Nicolas et Laurent Fedi, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2008, p.8

- ↑ Meyer, Catherine (edited by). Le livre noir de la psychanalyse: Vivre, penser et aller mieux sans Freud. Paris: Les Arènes, 2005, p.217

- ↑ Altschule, Mark. Origins of Concepts in Human Behavior. New York: Wiley, 1977, p.199

- ↑ Geraskov, Emil Asenov (November 1, 1994). "The internal contradiction and the unconscious sources of activity". Journal of Psychology. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013.

This article is an attempt to give new meaning to well-known experimental studies, analysis of which may allow us to discover unconscious behavior that has so far remained unnoticed by researchers. Those studies confirm many of the statements by Freud, but they also reveal new aspects of the unconscious psychic. The first global psychological concept of the internal contradiction as an unconscious factor influencing human behavior was developed by Sigmund Freud. In his opinion, this contradiction is expressed in the struggle between the biological instincts and the self.

- ↑ For example, dreaming: Freud called dream symbols the "royal road to the unconscious"

- ↑ Wayne Weiten (2011). Psychology: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. p. 6. ISBN 9780495813101.

- ↑ Jung, Carl; et al. (1964). "Man and His Symbols".

Sigmund Freud was the pioneer who first tried to explore empirically the unconscious background of consciousness. He worked on the general assumption that dreams are not a matter of chance but are associated with conscious thoughts and problems. This assumption was not in the least arbitrary. It was based upon the conclusion of eminent neurologists (for instance, Pierre Janet) that neurotic symptoms are related to some conscious experience. They even appear to be split-off areas of the conscious mind, which, at another time and under different conditions, can be conscious.

- ↑ 'Une histoire des sciences humaines, sous la direction de J.-F. Dortier, éditions Sciences humaines, 2006, ISBN 9782912601360 - part : 1900-1950 "Le temps des fondations" ; chapter about Freud

- ↑ "collective unconscious (psychology) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia." Encyclopedia - Britannica Online Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 Dec. 2011. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/125572/collective-unconscious>.

- ↑ Campbell, J. (1971). Hero with a thousand faces. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

- ↑ "Jung, Carl Gustav." The Columbia encyclopedia. 6th. ed. Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2000. 1490. Print.

- ↑ Vitz, Paul C. (1988). Sigmund Freud's Christian Unconscious. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-89862-673-0.

- ↑ Fromm, Erich. Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx & Freud. London: Sphere Books, 1980, p. 93

- ↑ Searle, John. The Rediscovery of the Mind. MIT Press, 1994, pp. 151-173

- 1 2 See "A Profession in Crisis", Chapter 1 of Therapy's Delusions: The Myth of the Unconscious and the Exploitation of Today's Walking Worried, published by Scribner, 1999

- ↑ Weber, Eric Thomas (2012) "James's Critiques of the Freudian Unconscious – 25 Years Earlier," William James Studies 9, 94–119.

- ↑ List of his publications at retrieved April 18, 2007

- ↑ Kihlstrom, J.F. (2002). "The unconscious". In Ramachandran, V.S. Encyclopedia of the Human Brain. 4. San Diego CA: Academic. pp. 635–646.

- ↑ Kihlstrom, J.F.; Beer, J.S.; Klein, S.B. (2002). "Self and identity as memory". In Leary, M.R.; Tangney, J. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 68–90.

- ↑ Wilson T D Strangers to Ourselves Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious

- ↑ Loftus EF, Klinger MR (June 1992). "Is the unconscious smart or dumb?". Am Psychol. 47 (6): 761–5. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.6.761. PMID 1616173.

- ↑ Greenwald AG, Draine SC, Abrams RL (September 1996). "Three cognitive markers of unconscious semantic activation". Science. 273 (5282): 1699–702. doi:10.1126/science.273.5282.1699. PMID 8781230.

- ↑ Gaillard R, Del Cul A, Naccache L, Vinckier F, Cohen L, Dehaene S (May 2006). "Nonconscious semantic processing of emotional words modulates conscious access". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (19): 7524–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600584103. PMC 1464371

. PMID 16648261.

. PMID 16648261. - ↑ Kiefer M, Brendel D (February 2006). "Attentional modulation of unconscious "automatic" processes: evidence from event-related potentials in a masked priming paradigm". J Cogn Neurosci. 18 (2): 184–98. doi:10.1162/089892906775783688. PMID 16494680.

- ↑ Naccache L, Gaillard R, Adam C, et al. (May 2005). "A direct intracranial record of emotions evoked by subliminal words". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (21): 7713–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500542102. PMC 1140423

. PMID 15897465.

. PMID 15897465. - ↑ Smith, E.R.; DeCoster, J. (2000). "Dual-Process Models in Social and Cognitive Psychology: Conceptual Integration and Links to Underlying Memory Systems". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 4 (2): 108–131. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_01.

- 1 2 3 Wayne Weiten (2011). Psychology: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. pp. 166–167. ISBN 9780495813101.

- ↑ Augusto, L.M. (2010). "Unconscious knowledge: A survey". Advances in Cognitive Psychology. 6: 116–141. doi:10.2478/v10053-008-0081-5.

- ↑ Hasher L, Zacks RT (December 1984). "Automatic processing of fundamental information: the case of frequency of occurrence". Am Psychol. 39 (12): 1372–88. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.39.12.1372. PMID 6395744.

- ↑ Connolly, Deborah Ann (1993). A developmental evaluation of frequency information in lists, scripts, and stories (M.A. thesis) Wilfrid Laurier University

References

- Jon Mills, Underworlds: Philosophies of the Unconscious from Psychoanalysis to Metaphysics. Routledge, 2014

- Matt Ffytche, The Foundation of the Unconscious: Schelling, Freud and the Birth of the Modern Psyche, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Jon Mills, The Unconscious Abyss: Hegel's Anticipation of Psychoanalysis, SUNY Press, 2002.

- S. J. McGrath, The Dark Ground of Spirit: Schelling and the Unconscious, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.

External links

- Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind, "Implicit Memory"

- Nonconscious Acquisition of Information (a reprint from American Psychologist, 1992)

- The Rediscovery of the Unconscious

- Nonconscious Acquisition of Information (a reprint from American Psychologist, 1992)