Underwater habitat

Underwater habitats are underwater structures in which people can live for extended periods and carry out most of the basic human functions of a 24-hour day, such as working, resting, eating, attending to personal hygiene, and sleeping. In this context 'habitat' is generally used in a narrow sense to mean the interior and immediate exterior of the structure and its fixtures, but not its surrounding marine environment. Most early underwater habitats lacked regenerative systems for air, water, food, electricity, and other resources. However, recently some new underwater habitats allow for these resources to be delivered using pipes, or generated within the habitat, rather than manually delivered.[1]

An underwater habitat has to meet the needs of human physiology and provide suitable environmental conditions, and the one which is most critical is breathing air of suitable quality. Others concern the physical environment (pressure, temperature, light, humidity), the chemical environment (drinking water, food, waste products, toxins) and the biological environment (hazardous sea creatures, microorganisms, fungi). Much of the science covering underwater habitats and their technology designed to meet human requirements is shared with diving, diving bells, submersible vehicles and submarines, and spacecraft.

Numerous underwater habitats have been designed, built and used around the world since the early 1960s, either by private individuals or by government agencies. They have been used almost exclusively for research and exploration, but in recent years at least one underwater habitat has been provided for recreation and tourism. Research has been devoted particularly to the physiological processes and limits of breathing gases under pressure, for aquanaut and astronaut training, as well as for research on marine ecosystems.

Basic types of habitats

Underwater habitats are designed to operate in two fundamental modes.

- Open to ambient pressure via a moon pool, meaning the air pressure inside the habitat equals underwater pressure at the same level, such as SEALAB, and which makes entry and exit easy as there is no physical barrier other than the moon pool water surface. Living in ambient pressure habitats is a form of saturation diving, and return to the surface will require appropriate decompression.

- Closed to the sea by hatches, with internal air pressure less than ambient pressure and at or closer to atmospheric pressure; entry or exit to the sea requires passing through hatches and an airlock. Decompression may be necessary when entering the habitat after a dive. This would be done in the airlock.

A third or composite type has compartments of both types within the same habitat structure and connected via airlocks, such as Aquarius (laboratory).

Historic underwater habitats

Conshelf I, II and III

Conshelf, short for Continental Shelf Station, was a series of undersea living and research stations undertaken by Jacques Cousteau's team in the 1960s. The original design was for five of these stations to be submerged to a maximum depth of 300 metres (1,000 ft) over the decade; in reality only three were completed with a maximum depth of 100 metres (330 ft). Much of the work was funded in part by the French Petrochemical industry, who, along with Cousteau, hoped that such manned colonies could serve as base stations for the future exploitation of the sea. Such colonies did not find a productive future, however, as Cousteau later repudiated his support for such exploitation of the sea and put his efforts toward conservation. It was also found in later years that industrial tasks underwater could be more efficiently performed by undersea robot devices and men operating from the surface or from smaller lowered structures, made possible by a more advanced understanding of diving physiology. Still, these three undersea living experiments did much to advance man's knowledge of undersea technology and physiology, and were valuable as "proof of concept" constructs. They also did much to publicize oceanographic research and, ironically, usher in an age of ocean conservation through building public awareness. Along with Sealab and others, it spawned a generation of smaller, less ambitious yet longer-term undersea habitats primarily for marine research purposes.

Conshelf I (Continental Shelf Station), constructed in 1962 was the first inhabited underwater habitat. Developed by Jacques-Yves Cousteau to record basic observations of life underwater, Conshelf I was submerged in 10 metres (33 ft) of water near Marseilles, and the first experiment involved a team of two spending seven days in the habitat. The two oceanauts, Albert Falco and Claude Wesly, were expected to spend at least five hours a day outside the station, and were subject to daily medical exams.

Conshelf Two, the first ambitious attempt for men to live and work on the sea floor, was launched in 1963. In it, a half-dozen oceanauts lived 10 metres (33 ft) down in the Red Sea off Sudan in a starfish-shaped house for 30 days. The undersea living experiment also had two other structures, one a submarine hangar that housed a small, two-man submarine referred to as the "diving saucer" for its resemblance to a science fiction flying saucer, and a smaller "deep cabin" where two oceanauts lived at a depth of 30 metres (100 ft) for a week. They were among the first to breathe a mixture of helium and oxygen, avoiding the normal nitrogen/oxygen mixture which when breathed under pressure can cause narcosis. The deep cabin was also an early effort in saturation diving, in which the oceanauts' body tissues were allowed to become totally saturated by the helium in the breathing mixture, a result of breathing the gases under pressure. Normally, this would prove fatal when the team returned to the surface, at which time reduced pressure would cause the helium to bubble out into the divers joints and tissues, afflicting them with the bends. The conventional solution would have been to subject the divers to lengthy and complex decompression; however, in this case the divers' instead breathed an oxygen-rich mixture of gases for a few hours before returning to the surface in order to purge the excess helium from their tissues. They suffered no apparent ill effects.

The undersea colony was supported with air, water, food, power, all essentials of life, from a large support team above. Men on the bottom performed a number of experiments intended to determine the practicality of working on the sea floor and were subjected to continual medical examinations. Conshelf II was a defining effort in the study of diving physiology and technology, and captured wide public appeal due to its dramatic "Jules Verne" look and feel. A Cousteau-produced feature film about the effort was awarded an Academy Award for Best Documentary the following year.[2]

Conshelf III was initiated in 1965. Six divers lived in the habitat at 102.4 metres (336 ft) in the Mediterranean near the Cap Ferrat lighthouse, between Nice and Monaco, for three weeks. In this effort, Cousteau was determined to make the station more self-sufficient, severing most ties with the surface. A mock oil rig was set up underwater, and divers successfully performed several industrial tasks.

SEALAB I, II and III

SEALAB was developed by the United States Navy, primarily to research the physiological aspects of saturation diving.[3][4][5]

Tektite I and II

The Tektite underwater habitat was constructed by General Electric and was funded by NASA, the Office of Naval Research and the Department of the Interior.[6]

On February 15, 1969, four U.S. Department of the Interior scientists (Ed Clifton, Conrad Mahnken, Richard Waller and John VanDerwalker) descended to the ocean floor in Great Lameshur Bay in the U.S. Virgin Islands to begin an ambitious diving project dubbed "Tektite I". By March 18, 1969, the four aquanauts had established a new world's record for saturated diving by a single team. On April 15, 1969, the aquanaut team returned to the surface after performing 58 days of marine scientific studies. More than 19 hours of decompression were needed to safely return the team to the surface.

Inspired in part by NASA's budding Skylab program and an interest in better understanding the effectiveness of scientists working under extremely isolated living conditions, Tektite was the first saturation diving project to employ scientists rather than professional divers.

The name Tektite generally refers to a class of meteorites formed by extremely rapid cooling. These include objects of celestial origins that strike the sea surface and come to rest on the bottom (note project Tektite's conceptual origins within the U.S space program).

The Tektite II missions were carried out in 1970. Tektite II comprised ten missions lasting 10–20 days with four scientists and an engineer on each mission. One of these missions included the first all-female aquanaut team, led by Dr. Sylvia Earle. Other scientists participating in the all-female mission included Dr. Renate True of Tulane, as well as Ann Hartline and Alina Szmant, graduate students at Scripps Institute of Oceanography. The fifth member of the crew was Margaret Ann Lucas, a Villanova engineering graduate, who served as Habitat Engineer. The Tektite II missions were the first to undertake in-depth ecological studies.[7]

Tektite II included 24 hour behavioral and mission observations of each of the missions by a team of observers[8] from the University of Texas at Austin. Selected episodic events and discussions were videotaped using cameras in the public areas of the habitat. Data about the status, location and activities of each of the 5 members of each mission was collected via key punch data cards every 6 minutes during each mission. This information was collated and processed by BellComm[9] and was used for the support of papers written[10] about the research concerning the relative predictability of behavior patterns of mission participants in constrained, dangerous conditions for extended periods of time, such as those that might be encountered in manned spaceflight.

The Tektite habitat was designed and built by General Electric Space Division at the Valley Forge Space Technology Center in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. The Project Engineer who was responsible for the design of the habitat was Brooks Tenney, Jr. Brooks also served as the underwater Habitat Engineer on the International Mission, the last mission on the Tektite II project. The Program Manager for the Tektite projects at General Electric was Dr. Theodore Marton.

Hydrolab

Hydrolab was constructed in 1966 and used as a research station from 1970. The project was in part funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Hydrolab could house 4 people. Approximately 180 Hydrolab missions were conducted; 100 missions in the Bahamas during the early to mid-1970s, and 80 missions in St. Croix, United States Virgin Islands, from 1977 to 1985. These scientific missions are chronicled in the Hydrolab Journal.[11]

Dr. William Fife spent 28 days in saturation performing physiology experiments on researchers such as Dr. Sylvia Earle.[12][13]

The habitat was decommissioned in 1985 and placed on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National History Museum in Washington, D.C.. The habitat is now located at the headquarters of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Silver Spring, MD.

Helgoland

Existing underwater habitats

Aquarius

Aquarius is presently one of the world's only three operational underwater laboratories. It is located adjacent to a coral reef in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.[14]

Marine Lab

The Marine Lab underwater laboratory is the longest serving seafloor habitat in history, having operated continuously in an unbroken service since 1984 under the direction of aquanaut Chris Olstad at Key Largo, Florida. The seafloor laboratory has trained hundreds of individuals in that time featuring an extensive array of educational and scientific investigations from United States military investigations to pharmaceutical development.

Beginning with a project initiated in 1973, MarineLab, then known as MEDUSA (Midshipman Engineered & Designed Undersea Systems Apparatus), was designed and built as part of an ocean engineering student program at the United States Naval Academy under the direction of Dr. Neil T. Monney. In 1983, MEDUSA was donated to the Marine Resources Development Foundation (MRDF), and in 1984 was deployed on the seafloor in John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, Key Largo, Florida. The 2.4-by-4.9-metre (8 by 16 ft) shore-supported habitat supports 3-4 persons and is divided into a laboratory, a wet-room, and a 1.7-metre-diameter (5 ft 7 in) transparent observation sphere. From the beginning, it has been used by students for observation, research, and instruction. In 1985, it was renamed MarineLab and moved to the 9-metre-deep (30 ft) mangrove lagoon at MRDF headquarters in Key Largo at a depth of 8.3 metres (27 ft) with a hatch depth of 6 m (20 ft). The lagoon contains artifacts and wrecks placed there for education and training. From 1993-95, NASA used MarineLab repeatedly to study Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELLS). These education and research programs qualify MARINE-LAB as the world’s most extensively used habitat.

MarineLab is also used as an underwater lab for excursions and underwater lab training for recreational and sport divers who stay under the sea at the Jules' Undersea Lodge. MarineLab is currently located right next to the Jules' Undersea Lodge which is actually the La Chalupa Research Laboratory converted into a luxury underwater habitat. Features include a large movie selection and specialty menus, including underwater pizza delivered by a diver. There is a cable running along the bottom of the lagoon that divers can follow at night or in reduced visibility to reach MarineLab which is a short distance from the Jules' Undersea Lodge. Basically, MarineLab is set up to do lab work and to serve as an underwater science classroom and the Jules' Undersea Lodge is used as an underwater habitat base where the participants can stay over night, rest, relax and dine in comfort.

MarineLab was used as an integral part of the "Scott Carpenter, Man in the Sea" Program.[15]

La Chalupa Research Laboratory

In the early 1970s, Ian Koblick, president of Marine Resources Development Foundation, developed and operated the La Chalupa research laboratory, which was the largest and most technologically advanced underwater habitat of its time. Koblick, who has continued his work as a pioneer in developing advanced undersea programs for ocean science and education, is the co-author of the book Living and Working in the Sea and is considered one of the foremost authorities on undersea habitation.

La Chalupa was operated off Puerto Rico. During the habitat's launching for its second mission, a steel cable wrapped around Dr. Lance Rennka's left wrist, shattering his arm, which he subsequently lost to gas gangrene.[16]

In the mid-1980s La Chalupa was transformed into Jules' Undersea Lodge in Key Largo, Florida. Jules' co-developer Dr. Neil Monney formerly served as Professor and Director of Ocean Engineering at the U.S. Naval Academy, and has extensive experience as a research scientist, aquanaut, and designer of underwater habitats.

Jules' has had over 10,000 overnight guests in its 30 years of operation. Today many certified divers who are interested stay in the Jules' Underwater Lodge, and some who meet the skill and bottom time requirements and participate in underwater experiments in the MarineLab can elect to receive specialty diver recognition from PADI or NAUI as a Recreational Aquanaut. This is the only recreational Aquanaut qualification available worldwide. Today Aquanaut Hotel guests must scuba dive to get down to the hotel, and a nearby landbase offers diving lessons for people who are unfamiliar with the activity. Years ago non-scuba diving guests were taken down to the lodge breathing air pumped down from the surface through a long hose similar to a garden hose but this practice was discontinued and now all guests must scuba dive to the lodge entrance five fathoms below. The air hose system has been replaced by a hooka rig featuring modern scuba regulator second stages and is often used by guests as well as the operations crew to get back and forth to the lodge without donning scuba gear.

La Chalupa was used as the primary platform for the Scott Carpenter Man in the Sea Program, an underwater analog to Space Camp. Unlike Space Camp, which utilizes simulations, participants performed scientific tasks while using actual saturation diving systems. This program, envisioned by Ian Koblick and Scott Carpenter, was directed by Phillip Sharkey with operational help of Chris Olstad. Also used in the program was the MarineLab Underwater Habitat, the submersible Sea Urchin (designed and built by Phil Nuytten), and an Oceaneering Saturation Diving system consisting of an on deck decompression chamber and a diving bell. La Chalupa was the site of the first underwater computer chat, a session hosted on GEnie's Scuba RoundTable (the first non-computing related area on GEnie) by then Scott Carpenter Man in the Sea Director Sharkey from inside the habitat. Divers from all over the world were able to direct questions to him and to Commander Carpenter.

Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station

The Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station was launched near Key Largo on six-week missions in 1997 and 1998.[17] The station was a NASA project illustrating the analogous science and engineering concepts common to both undersea and space missions. During the missions, some 20 aquanauts rotated through the undersea station including NASA scientists, engineers and director James Cameron. The SCSAS was designed by NASA engineer Dennis Chamberland.[17]

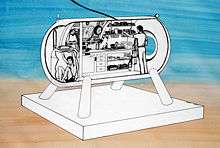

Lloyd Godson's Biosub

Lloyd Godson's Biosub was an underwater habitat, built in 2007 for a competition by Australian Geographic. The Biosub [18] generated its own electricity (using a bike),its own water, using the Air2Water Dragon Fly M18 system, its own air (using algae that produce O2). The algae were fed using the Cascade High School Advanced Biology Class Biocoil.[19] The habitat shelf itself was constructed by Trygons Designs.

Galathée

The first underwater habitat built by Jacques Rougerie was launched and immersed on 4 August 1977.[20] The unique feature of this semi-mobile habitat-laboratory is that it can be moored at any depth between 9 and 60 metres, which gives it the capability of phased integration in the marine environment. This habitat therefore has a limited impact on the marine ecosystem and is easy to position. Galathée was experienced by Jacques Rougerie himself.[21][22]

Aquabulle

Launched for the first time in March 1978, this underwater shelter suspended in midwater (between 0 and 60 metres) is a mini scientific observatory 2.8 metres high by 2.5 metres in diameter.[23] The Aquabulle, created and experienced by Jacques Rougerie, can accommodate three people for a period of several hours and acts as an underwater refuge. A series of Aquabulles were later built and some are still being used by laboratories.[20][24]

Hippocampe

This underwater habitat, created by a French Architect, Jacques Rougerie, was launched in 1981 to act as a scientific base suspended in midwater using the same method as Galathée.[23] Hippocampe can accommodate 2 people on saturation dives up to a depth of 12 metres for periods of 7 to 15 days, and was also designed to act as a subsea logistics base for the offshore industry. [20]

Conceptual underwater habitats

Sub-Biosphere 2

A concept design by internationally recognized conceptual designer and futurist Phil Pauley.[25] The Sub-Biosphere 2 is the original self sustainable underwater habitat designed for aquanauts, tourism and oceanographic life sciences and longterm human, plant and animal habitation.[26] SBS2 is a seed bank with eight Living Biomes to allow human, plant and fresh water interaction, powered and controlled by the Central Support Biome which monitors the life systems from within its own operations facility.

In popular culture

- The Aquanox series occurs in a post-apocalyptic scenario where humanity had to descend into the depths of the ocean permanently, and hence features entire cities of underwater habitats.

- The Abyss, DeepStar Six, and Leviathan are all 1989 movies set in underwater habitats.

- Ocean Girl, an Australian series that features a massive underwater research facility called ORCA.

- Deep Blue Sea, a movie that features scientists working in a large underwater lab station called Aquatica.

- Diving Adventure, a novel by author Willard Price, features an Undersea City clearly inspired by Cousteau's underwater habitat projects.

- Captain Nemo and the Underwater City, much of this movie takes place in an underwater city, named Templemir, built by Captain Nemo and his followers.

- The BioShock video game series takes place in Rapture, a secretly-built underwater city.

- Champions Online, an MMORPG featuring an underwater city called Lumeria

- Deus Ex, a video game, features an underwater research laboratory called OceanLab.

- Sealab 2020, an animated series from the 1970s, takes place in a fictional underwater research lab, as does Cartoon Network's reworking of the show, Sealab 2021.

- Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea

- SeaQuest DSV featured numerous underwater colonies, research facilities, and military installations.

- Sphere, a novel that takes place in an underwater habitat.

- Various episodes of the BBC educational series Science in Action featured an Underwater Habitat that could house a U-Boat.

- In The Spy Who Loved Me, the film's villain, Karl Stromberg, lives in an underwater fortress.

- The TV series Stingray featured an underwater complex.

- Lost, a building known as the Looking Glass is an underwater station built by the Dharma Initiative.

- Ever 17, A game that tells the story of seven people who are trapped in an underwater theme park (LeMU) and their struggle to escape.

- Call of Duty: Black Ops, In the final mission the player attacks an underwater fortress

- Hello Down There, a movie about a family living in an underwater house.

- Knights of the Old Republic, a Star Wars-based game features a section that include an underwater habitat.

- Starfish, a science-fiction novel by Peter Watts, centers around an underwater habitat named after William Beebe.

- Crisis on Conshelf Ten, a children's science-fiction novel by Monica Hughes.

- 11 A.M., in the science fiction film researchers at a deep-sea laboratory invent a time machine which can move objects ahead 24 hours. At the first test sending people to the future they find the base in pandemonium, while the other researchers have disappeared.[27]

- Lords of the Deep, in a near future ocean where the Earth's ozone layer has been depleted and new means of habitation and survival are being explored an undersea laboratory gets attacked by large stingray-like creatures.

- SOMA, a 2015 video game, takes place on the fictional PATHOS-II, an underwater research facility.

- In the 2009 science fiction novel Ark by Stephen Baxter deep submarine seismic activity leads to seabed fragmentation, and the opening of deep subterranean reservoirs of water with human civilization getting almost destroyed by the rising inundation. Three "arks" are built for survival with the secret "Ark Two" turning out to be an underwater habitat powered by the geothermal heat of Yellowstone.

- Deep Fear, a 1998 video game released for the Sega Saturn, is set in a massive, underwater facility known as The Big Table.

- X-COM: Terror from the Deep is a 1995 PC video game in which the player builds multiple underwater bases to combat aliens.

See also

- Ichthyander Project, a Soviet amateur project of the 1960s

- Artificial gills (human), a method to harvest air from water

- Saturation diving

- Human outpost

- NEEMO

References

- ↑ Regenerative water and air supply in underwater habitat - 23 Apr 2007, By Sandrine Ceurstemont, FirstScience.com

- ↑ "The 37th Academy Awards | 1965". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ↑ Clarke TA, Flechsig AO, Grigg RW (September 1967). "Ecological studies during Project Sealab II. A sand-bottom community at depth of 61 meters and the fauna attracted to "Sealab II" are investigated". Science. 157 (3795): 1381–9. Bibcode:1967Sci...157.1381C. doi:10.1126/science.157.3795.1381. PMID 4382569. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ Kuling JW, Summitt JK (1970). "Saturation Dives, with Excursions, for the Development of a Decompression Schedule for Use during SEALAB III.". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine Technical Report. NEDU-RR-9-70. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ Crowley RW, Summitt JK (1970). "Report of Experimental Dives for SEALAB III Surface Support Decompression Schedules.". US Navy Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-RR-15-70. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ Starck WA, Miller JW (September 1970). "Tektite: expectations and costs". Science. 169 (3952): 1264–5. Bibcode:1970Sci...169.1264S. doi:10.1126/science.169.3952.1264-a. PMID 5454136. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ Collette, BB (1996). "Results of the Tektite Program: Ecology of coral-reef fishes. In: MA Lang, CC Baldwin (Eds.) The Diving for Science...1996, "Methods and Techniques of Underwater Research"". Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences Sixteenth Annual Scientific Diving Symposium, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ↑ TEKTITE II Behavior Observer's Manual UT Austin, 1970

- ↑ Tektite II Data Management/Handling Case 103-7 September 28, 1970 by M.J. Reynolds

- ↑ The TEKTITE II Human Behavior Program September, 1971, UT Austin, Robert Helmreich

- ↑ Hydrolab Journal OCLC number 3289185

- ↑ Fife, William P, Schroeder, W (1973). "Effects of the Hydrolab environment on pulmonary function". Hydrolab J. 2: 73.

- ↑ Fife, William P, Schroeder, W (1973). "Measurement of metabolic rate in aquanauts". Hydrolab J. 2: 81.

- ↑ Shepard AN, Dinsmore DA, Miller SL, Cooper CB, Wicklund RI (1996). "Aquarius undersea laboratory: The next generation". In: MA Lang, CC Baldwin (Eds.) The Diving for Science...1996, "Methods and Techniques of Underwater Research". Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (Sixteenth annual Scientific Diving Symposium). Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Tracy Kornfeld - WOWIE Web Design. "Sealab".

- ↑ Ecott, Tim (2001). Neutral Buoyancy: Adventures in a Liquid World. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 275. ISBN 0-87113-794-1. LCCN 2001018840.

- 1 2 "Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station". NASA Quest. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ↑ "BioSUB". LLOYD GODSON.

- ↑ BioSub specifics

- 1 2 3 SeaOrbiter's Website

- ↑ Jacques Rougerie, un architecte de la mer "immortel". 25 November 2009 – via YouTube.

- ↑ De Vingt milles lieues sous les mers à SeaOrbiter, plongez dans l'univers de Jacques Rougerie. 27 November 2012 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 EURONEWS - SeaOrbiter - The vessel on and under the oceans - En. 15 June 2012 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Du Nautilus à SeaOrbiter - Grande Histoire des Océans - Arte. 28 June 2012 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Phil Pauley - Sustainability - Futurology - Singularity". Phil Pauley - Sustainability - Futurology - Singularity.

- ↑ "Could we all soon be sleeping with the fishes? Designer creates incredible futuristic city where people live beneath the waves". Mail Online. 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Sunwoo, Carka (22 November 2013). "11 A.M. takes audiences back to the near future". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

- General

- Gregory Stone: "Deep Science". National Geographic Online Extra (Sept 2003). Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- BBC. Living under the sea

- Miller, James W., Koblick, Ian G. 1997. Living and Working in the Sea

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Undersea habitats. |

- Jules' Undersea Lodge

- Phil Pauley

- Underwater habitat in formation Oceanic Ecovillage

- US Naval Undersea Museum SEALAB II Display

- Concrete underwater habitat

- Underwater Habitation Research