Unidentified decedent

Unidentified decedent or unidentified person (also abbreviated as UID or UP) is a term in American English used to describe a corpse of a person whose identity cannot be established by police and medical examiners. In many cases, it is several years before the identities of some UIDs are found, while in some cases, they are never identified.[1] A UID may remain unidentified due to lack of evidence as well as absence of personal identification such as a driver's license. Where the remains have deteriorated or mutilated to the point that the body is not easily recognized, a UID's face may be reconstructed to show what it had looked like before death.[2] UIDs are often referred to by the placeholder names "John Doe" or "Jane Doe".[3]

Causes

There are approximately 40,000 UIDs in the United States,[4][5][6] and numerous others elsewhere.[7] A body may go unidentified due to death in a state where the person was unrecorded, an advanced state of decomposition or major facial injuries.[8]

Location

Some UIDs die outside their native state. The Sumter County Does, murdered in South Carolina, may have been Canadian.[9] Barbara Hess Precht died in Ohio in 2006 but was not identified until 2014. She had been living as a transient with her husband in California for decades but returned to her native state of Ohio, where she died of unknown circumstances.[10] In both of these cases, the UIDs were found in a recognizable state and had their fingerprints and dental records taken with ease. It is unknown if the Sumter County Does' DNA was later recovered, since their bodies would require exhumation to recover DNA.[9] In Lourdes, France, a corpse believed to have been native to a different country was discovered.[11] Many illegal immigrants that die in the United States after crossing the border from Mexico remain unidentified.[12]

Decomposition

Many UIDs are found long after they die and have decomposed severely. This significantly changes their facial features and may prevent identification through fingerprints. Environmental conditions often are a major factor in decomposition, as some UIDs are found months after death with little decomposition if their bodies are placed in cold areas. Some are found in warm areas shortly after death, but hot temperatures and scavenging animals deteriorated the features.[8][13][14] In some cases, warm temperatures mummify the corpse, which also distorts its features, though the tissues have survived initial decomposition. One example is the "Persian Princess", who died in the 1990s but, in an act of archaeological forgery, was untruthfully stated in Pakistan to have been over 2,000 years old.[15] A man found in Idar-Oberstein, Germany, in 1994 had died months before his body was found, yet in some places, his skin had not deteriorated and tattoos were found, which are also used to identify the dead.[16]

Putrefaction

Putrefaction often occurs when bacteria decompose the remains and generate gasses inside, causing the corpse to swell and become discolored.[8] In cases such as the Rogers family, who were murdered in 1989 by Oba Chandler, the bodies were deposited in water but surfaced after gasses in their remains caused them to float to the surface. They were deceased a short period of time but were already severely decomposed and unrecognizable, due to putrefaction that occurred while underwater and high temperatures. It was not until a week later that dental records revealed their identities.[17]

Skeletonization

Skeletonization occurs when the UID has decayed to the point that bones and possibly some tissues are all that is found, usually when death occurred a significant amount of time before discovery. If a skeletonized body is found, fingerprints and toeprints are impossible to recover, unless they have survived the initial decomposition of the remains. Fingerprints are often used to identify the dead and were used widely before DNA comparison was possible.[8] In some cases, partial remains limit the available information; for example, a woman's skull found in Frankfurt, Germany, was insufficient to estimate her height and weight.[18]

Skeletonized UIDs are often forensically reconstructed if searching dental records and DNA databases is unsuccessful.

Traumatic injuries

Some UIDs experience trauma that significantly alters their appearance, especially those who die in vehicular accidents or were murdered in a violent manner. A facial expression often represents the pain, which shifts the face into a position that would not commonly be seen by the public, including those who have seen the person when they were alive. A body found decapitated would also prove to be unrecognizable.[19] Many UIDs whose heads were not recovered remain unidentified, like in the Whitehall Mystery, which occurred in the United Kingdom.[20]

Burning

Often, someone who tries to conceal a body attempts to destroy it or render it unrecognizable.[21] The currently unidentified Yermo John Doe was killed approximately one hour before he was found, but was completely unrecognizable.[22] When Lynn Breeden, a Canadian model, was murdered and set ablaze in a dumpster, her body was so severely damaged that DNA processing and fingerprint analysis were impossible. She was identified sometime later after her unique dentition matched her own dental records, and DNA extracted from her blood at a different scene was matched.[23] Linda Agostini's body was found burned near Albury, Australia in 1934. Her remains were identified ten years later through dental comparison.[24]

Identification process

Usually, bodies are identified by comparing their usually unique DNA, fingerprints and dental characteristics.[25] DNA is considered the most accurate, but was not as widely used until the 1990s. It is often obtained through hair follicles, blood, tissue and other biological material.[26] Bodies can also be identified with other physical information, such as illnesses, evidence of surgery, breaks and fractures, and height and weight information.[27] A medical examiner will often be involved with identifying a body.[28][29]

Mortuary photographs

Many police departments and medical examiners have made efforts to identify the deceased by placing mortuary photographs of the UID's face online. In some instances, the mortuary photographs would be retouched of wounds if they are to be released to the public.[30] Dismembered corpses may also be digitally altered to appear attached to the body.[19] This is not considered to be the most effective method, as the nature of death often distorts the UID's face.[31] An example of this is that of "Grateful Doe," who was killed in a vehicular crash in 1995. He sustained extreme trauma that disfigured his face.[32]

A Jane Doe found in a river in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, had died months earlier, but was preserved by the cold temperatures. Her morgue photographs were displayed publicly on a medical examiner's website, but her face had been distorted by swelling after absorbing water, with additional decomposition.[33]

Death masks have also been used to assist with identification, which have been stated to be more accurate, as they are required to display "relaxed expressions," which often do not illustrate the faces of the UIDs as they were found, such as that of L'Inconnue de la Seine, a French suicide victim found in the late 1800s.[34] However, a death mask will still depict sunken eyes or other characteristics of a long-term illness, which do not often show how they would have looked in life.[8]

Reconstructions

When a body is found in an advanced state of decomposition or has died violently, reconstructions are sometimes required to receive assistance from the public, when releasing images of a corpse is considered taboo.[35] Often, those in a recognizable state will often be reconstructed due to the same reason.

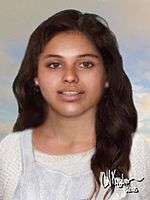

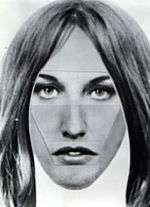

Faces can be reconstructed with a three-dimensional model or by 2D, which includes sketches or digital reconstructions, similar to facial composites.[36][37]

Sketches have been used in a variety of cases. Forensic artist Karen T. Taylor created her own method during the 1980s, which involved much more precise techniques, such as estimating locations and sizes of the features of a skull. This method has been shown to be fairly successful.[38]

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has developed methods to estimate the likenesses of the faces of UIDs whose remains were too deteriorated to create a two-dimensional sketch or reconstruction due to the lack of tissue on the bones. A skull would be placed through a CT scanner and the image would then be manipulated with a software that was intended for architecture design, to add digital layers of tissue based on the UID's age, sex and race.[39]

Examples

The following gallery depicts various ways UIDs have been reconstructed. None of those shown have been identified.

- Forensic sketch (Broward County John Doe (1979))

Reconstruction created with compiled photographs of facial features, a method known as IdentiKit (New Haven County Jane Doe)

Reconstruction created with compiled photographs of facial features, a method known as IdentiKit (New Haven County Jane Doe).jpg) Death mask (L'inconnue de la Seine)

Death mask (L'inconnue de la Seine).jpg) Three dimensional clay reconstruction (Caroline County John Doe)

Three dimensional clay reconstruction (Caroline County John Doe) Facial composite (Pinellas County John Doe)

Facial composite (Pinellas County John Doe) Reconstruction created through a CT scan (Lumberton Jane Doe)

Reconstruction created through a CT scan (Lumberton Jane Doe)

Problems

In some cases, such as that of Colleen Orsborn, the true identity of the unidentified person is excluded from the case. In Orsborn's case, she had fractured one of the bones in her leg, but a medical examiner who performed the autopsy on her remains was not able to discover evidence of the injury and subsequently excluded her from the case. It was not until 2011 when DNA confirmed Orsborn was the victim found in 1984.[40][41] In cases such as the Racine County Jane Doe, a rule out has also been subjected to criticism. Aundria Bowman, a teen who disappeared in 1989 who bore a strong resemblance to a body found in 1999, was excluded, according to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.[42] On an online forum, known as Websleuths, users have disagreed with this ruling.[43] In the case of Lavender Doe, a mother of a missing girl also disagreed with the exclusion of her missing daughter through DNA, as she claimed the reconstruction of the victim looked very similar to her daughter.[44]

Notable cases

Unidentified

- Whitehall Mystery, England, unidentified since 1888[45]

- Taman Shud Case, Australia, unidentified since 1948[46]

- Isdal Woman, Norway, unidentified since 1970[47]

- Sumter County Does, United States, unidentified since 1976[48]

- "Beth Doe", United States, unidentified since 1976[49]

- Orange Socks, United States, unidentified since 1979[50]

- Buckskin Girl, United States, unidentified since 1981.[51]

- Persian Princess, Pakistan, unidentified since 1996[52]

Formerly unidentified

- List of formerly unidentified decedents

- "Pyjama Girl", murdered in 1934 in Australia and identified in 1944 as Linda Agostini[53]

- "Tent Girl", murdered in 1968 and identified as Barbara Ann Hackmann Taylor in 1998[54]

- "Precious Doe", murdered in 2001 and identified as Erica Michelle Green in 2005[55]

- "Ballarat Bandit", committed suicide in 2004 and identified as a Canadian man, George Robert Johnston in 2006[56]

- "Baby Grace", murdered in 2007 and identified as Riley Ann Sawyers later that year[57]

- "DuPage Johnny Doe", murdered in 2005 and identified as Atcel Olmedo in 2011[58]

- "Baby Hope", murdered in 1991 and identified as Anjelica Castillo in 2013[59]

- "Pearl Lady", found in the Ohio River in 2006 and identified as Barbara Precht in 2014[60]

- Caledonia Jane Doe, found murdered in 1979 and identified in 2015 as Tammy Alexander[61]

- "Grateful Doe", died in a car accident in 1995 and identified in 2015 as Jason Callahan [62]

See also

- List of formerly unidentified decedents

- List of unidentified decedents in the United States

- Body identification

References

- ↑ "Resolved Cases". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ↑ Slott, Ellen L. (21 December 1977). "Sculptor Reconstructs Faces to Aid Police". The Evening Review. p. 3. Retrieved 21 July 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Why Are Unidentified People Called John or Jane Doe?". mentalfloss.com. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ↑ Sullivan, John (6 March 2006). "Missing/inaction Morgues hold about 40,000 sets of unidentified remains. Why isn't there a national database to help families find loved ones?". Philly.com. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "About NamUs". identifyus.org. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "The statistic stopped me in my tracks" (PDF). CBS. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Unidentified Persons Geographic Index - International". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Madea, Burkhard, Johanna Preuss, and Frank Musshoff. "From Flourishing Life to Dust-The Natural Cycle." Mummies of the World. Ed. Alfried Wieczorek and Wilfried Rosendahl. First ed. 2010. 28. Print.

- 1 2 "Bodies Remain Unidentified". The Daily Times-News. 19 September 1976. p. 10. Retrieved 7 August 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Dixon, Deb. "New Clues about 'Pearl Lady's' Husband". WKRC Cincinnati. CBS. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Case File 354UFFRA". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Stryker, Ace (2 April 2008). "In Southwest, illegal immigrants often die anonymously". Seattle Pi. Associated Press. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "NamUs UP # 10566". identifyus.org. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. August 27, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Pima Arizona Jane Doe April 1981". canyouidentifyme.org. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ Romey, Kristin M.; Rose, Mark (January–February 2001). "Special Report: Saga of the Persian Princess". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 54 (1). Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ "Case File 197UMDEU". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Bourdett, Paul, prod. "Water Logged." Forensic Files. Dir. Michael Jordan. HLN. 10 Dec. 2010. Television

- ↑ "Case File 469UFDEU". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- 1 2 Pravir Bodkha, Bishwanath Yadav (December 2012). "A Role of Digital Imaging in Identification of Unidentified Bodies" (PDF). J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 34 (4). ISSN 0971-0973. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Whitehall Mystery". www.futilitycloset.com. 16 October 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ Hayes, Ashley (13 February 2013). "How authorities identify a burned body". CNN. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "NamUs UP # 918". National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. 12 March 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ↑ Dowling, Paul. "Charred Remains." Forensic Files HLN. Atlanta, Georgia, 13 Nov. 1997. Television.

- ↑ Pennay, Bruce, "Agostini, Linda (1905 - 1934)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 2007-05-02

- ↑ Claridge, Jack (10 December 2014). "Identifying the Victim". Explore Forensics. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "8 Body Parts Forensic Scientists Use to ID a Body". Forensic Science Technician. 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ Valk, Diana (18 November 2013). "3 Ways to Identify a Body When DNA is Not An Option". Forensics Outreach. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "IDENTIFICATION PROCESS". virtualmuseum.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "POSTMORTEM IDENTIFICATION". Crime Library. 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ Friess, Steve (25 January 2004). "To identify 'John Doe' victims, investigators turn to the Web". Boston Globe. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Question: Why don't you share photos from the coroner's office?". Help ID Me. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. 7 May 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ Lohr, David (25 April 2014). "Grateful Dead Fan Remains Nameless, 18 Years After Fatal Crash". Huffington Post. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ↑ Luthern, Ashley (27 November 2014). "Investigators trying to solve mystery of woman found in 1982". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Chrisafis, Angelique (December 1, 2007). "Ophelia of the Seine". The Guardian Weekend magazine, page 17 - 27. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Izadi, Elahe (9 July 2015). "Can this computer generated image of a 'Baby Doe' lead investigators to her identity?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ Kilgannon, Corey (20 January 2015). "Through Art and Forensics, Faces of Unidentified Victims Emerge". New York Times. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ Martinez, Rick (9 May 1979). "Sculptor Reconstructs Faces to Aid Police". San Bernardo County Sun. p. 27. Retrieved 21 July 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Dowling, Paul. "Saving Face." Forensic Files. Prod. Paul Bourdett and Vince Sherry. Dir. Michael Jordan. 28 Nov. 2007.

- ↑ Hicks, Brad (29 February 2012). "Unraveling the Jane Doe Mystery". Fox News. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Resolved Case". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Prieto, Bianca (2 February 2011). "Dr. G links body found in Orange in 1984 to missing Daytona Beach teen girl". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "NamUs UP # 4741". NamUs.org. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ↑ "WI - Raymond (Racine County) - WhtFem 199UFWI, 14-25, July'99 *Graphic*". websleuths.com. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Sutton, Field (11 February 2014). "Brandi Well's mother reacts to Jane Doe renderings: "That looks so much like Brandi"". CBS. KTYX News. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Cullen, Tom (1965) Autumn of Terror, London: The Bodley Head, p. 95

- ↑ The Advertiser, "Tamam Shud", 10 June 1949, p. 2

- ↑ "The Isdal Woman". Futility Closet. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Warder, Robin (14 June 2013). "10 Mysterious Cases Involving Unidentified People". Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Dismembered body was girl who died of strangulation". The Evening Times. 23 December 1976. Retrieved 23 December 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Verhovek, Sam Howe (8 January 1992). "Death-row Inmate May Not Deserve Penalty". Indiana Gazette. p. 4. Retrieved 11 October 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Case File 133UFOH". The Doe Network. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ Romey, Kristin M.; Rose, Mark (January–February 2001). "Special Report: Saga of the Persian Princess". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 54 (1).

- ↑ "Agostini, Linda (1905–1934)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 1993. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ Wolfe, Charles. "Thirty years later, 'Tent Girl' homicide victim identified", Daily News, Bowling Green, Kentucky, 23 April 1998. Retrieved on 24 August 2014

- ↑ "Charges In 'Precious Doe' Case". CBS Broadcasting. 5 May 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2006.

- ↑ "He told me, 'One day I'm going to do something big.' I Guess He Did". The Vancouver Province. CanWest MediaWorks Publications. 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "DNA test confirms Riley is Baby Grace". Houston Chronicle. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "Break In Case Of Unknown Child Found Dead Five Years Ago". CBS Local. CBS. 18 February 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ "Report: 'Baby Hope's' Real Name Revealed 22 Years After Body Found". CBS. CBS New York. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Dixon, Deb. "A mystery mother's identity revealed". WKRC Cincinnati. 12 WKRC-TV. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Police ID 'Jane Doe' found in Livingston Co. cornfield in 1979". 26 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ "DNA identifies 'Grateful Doe' as missing Myrtle Beach man 20 years after disappearance". 9 December 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Unidentified decedents. |

- The Doe Network

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children

- National Missing and Unidentified Persons System

- FBI Unidentified Victims

- "Help ID Me" on Facebook