Vix Grave

The area around the village of Vix in northern Burgundy, France is the site of an important prehistoric complex from the Celtic Late Hallstatt and Early La Tène periods, comprising an important fortified settlement and several burial mounds. The most famous of the latter, the Vix Grave, also known as the grave of the Lady of Vix, dates to circa 500 BC. Her grave had never been looted and contained remarkably rich grave offerings (collectively sometimes known as the Trésor de Vix), including a great deal of jewellery and the Vix krater, the largest known metal vessel from Western classical antiquity, being 1.63 m (5'4") in height.[1]

Location

The sites are located near the village of Vix, about 6 km north of Châtillon-sur-Seine, in the Côte-d'Or department, northeastern Burgundy. The complex is centred on Mont Lassois, a steep flat-topped hill that dominates the area. It was the site of a fortified Celtic settlement, or oppidum. To the southeast of the hill, there was a 42-hectare necropolis with graves ranging from the Late Bronze Age via the Hallstatt Culture to Late La Tène. Other finds indicate activity up to Late Antiquity.[2]

During the sixth and fifth centuries BC, the Vix or, Mont Lassois, settlement appears to have been in control of an important trading node, where the Seine, an important riverine transport route linking eastern and western France, crossed the land route leading from the Mediterranean to Northern Europe. Additionally, Vix is at the centre of an agriculturally rich plain.

History of discovery

Discovery of archaeological material in the area, originally by a locally based amateur, began in April 1930. Increasingly systematic work throughout the following decades revealed thousands of pottery sherds, fibulae, jewellery, and other bronze and iron finds. The famous burial mound with the krater was excavated in early 1953 by René Jouffroi. In 1991 new archaeological research on and around Mont Lassois began under the direction of Bruno Chaume. Since 2001 a programme of research titled “Vix et son environnement” began, uniting the resources of several universities.[3]

The oppidum of Mont Lassois

Fortifications and architecture

Excavation of the settlement on the summit of Mont Lassois revealed extensive fortifications, with ditches and walls up to 8 m thick. The walls were built in the Pfostenschlitzmauer technique, but also yielded nails of the type common in murus gallicus walls. Excavation inside the enclosure revealed a variety of buildings, including post houses, pit dwellings, hearths, and storage units built on stilts. Geophysical work shows a large planned settlement, with a central, north–south axis and several phases of buildings.

The "Palace of the Lady of Vix"

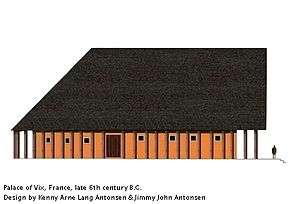

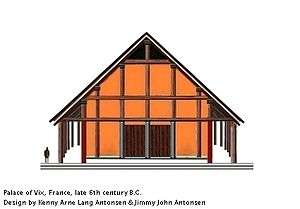

In 2006, a remarkable architectural unit was discovered at the centre of the site. It is a large complex of two or three buildings, the main one measuring 35 by 21 m, with an estimated height of 12 m: the dimensions of a modern church. The large hall had an apse at the back and a front porch in antis. Overall, the central unit resembles the megaron complex of early Greek architecture. Such a find is unprecedented in early Celtic Europe. Finds suggested domestic use or feasting uses. The structure has been described as the "Palace" of the Lady of Vix (Palais de la Dame de Vix).

Finds

The many individual finds from the Lassois oppidum clearly demonstrate the settlement's long and wide-ranging trade contacts, as well as its own role as an economic centre. The most common finds are shards of pottery, with more than 40,000 recorded to date. Many are local products, decorated with simple geometric motifs (checkerboard patterns) and occasional depictions of animals. There also have been finds of imported Attic black figure vases from Greece. Many amphorae and bowls could be identified as coming from the contemporary Greek-settled areas of Southern France. The amphorae had been used for transporting wine.

Jewellery included fibulae, commonly decorated with amber or coral, earrings, beads, slate bracelets, and rings. Glass ornaments also were found. Some small bronze figurines found are probably of Mediterranean origin. Little weaponry has been found as yet, the majority of it projectiles and axes.

Status

Mont Lassois has all the features of a high-status settlement: large fortifications, the presence of a citadel and a lower town, rare and fine imported materials, as well as numerous rich burial mounds in the vicinity.[4]

The burial mounds

The 1953 Vix Grave

The burial of "the Lady of Vix" took place around 500 B.C. Although decomposition of the organic contents of the grave was nearly total, the gender of the individual buried has been interpreted as female: she is accompanied by many items of jewellery, but no weaponry. Her social status is not clear and other than "Lady," names such as, Queen, Princess, or Priestess of Vix have all been used in various articles involving conjecture. There can be no doubt of her high status, as indicated by the large amounts of jewellery. She was between 30 years and 35 years old at the time of her death.

Burial and grave goods

The inhumation burial was placed in a 4m x 4m rectangular wooden chamber underneath a mound or tumulus of earth and stone which originally measured 42m in diameter and 5m in height.

Her body was laid in the freestanding box of a cart, or chariot, the wheels of which had been detached and placed beside it. Only its metal parts have survived. Her jewellery included a 480 gram 24-carat gold torc, a bronze torc, six fibulae, six slate bracelets, plus a seventh bracelet made of amber beads.

The grave also contained an assemblage of imported objects from Italy and the Greek world, all of them associated with the preparation of wine. They included the famous krater (see below), a silver phiale (shallow bowl, sometimes seen as a local product), an Etruscan bronze oinochoe (wine jug), and several drinking cups from Etruria and Attica. One of the latter was dated as c. 525 BC and represents the latest firmly dated find in the grave. It thus provides the best evidence, a terminus post quem for its date. The vessels probably were placed on wooden tables or benches that did not survive.

The Vix krater

The largest and most famous of the finds from the burial is an elaborately decorated bronze volute krater of 1.63m (5'4") height and over 200kg (450lbs) weight. Kraters were vessels for mixing wine and water, common in the Greek world, and usually made of clay. The Vix krater has become an iconic object representing both the wealth of early Celtic burials and the art of Late Archaic Greek bronze work.

- The krater was made of seven or more individual pieces with alphabetical markings, indicating that it probably was transported to Burgundy in pieces and assembled in situ.

- The vase proper, made of a single sheet of hammered bronze, weighs about 60kg. Its bottom is rounded, its maximum diameter is 1.27m, and its capacity is 1,100 litres (290 gallons). Its walls are only 1mm to 1.3mm thick. The krater was found crushed by the weight of the tumulus material above it. It had telescoped completely: the handles were found at the same level as the base. It was restored after excavation.

- Its foot is made of a single moulded piece, its diameter is 74cm, its weight 20.2kg. It received the rounded bottom of the main vase and ensured its stability. It is decorated with stylised plant motifs.

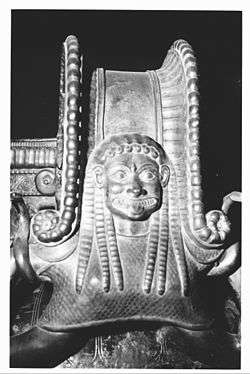

- The three handles, supported by rampant lionesses, weighed about 46kg each. Each is a 55cm high volute, each is elaborately decorated with a grimacing gorgon, a common motif on contemporary Greek bronzes.

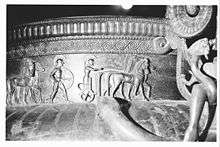

- A frieze of hoplites decorates the neck of the vessel, which is made of a bronze ring inserted into the main vase and supporting the handles. It depicts eight chariots, each drawn by four horses and conducted by a charioteer (depicted smaller than the hoplites for reasons of space), each is followed by a single fully armed hoplite on foot. The frieze is an important example of early Greek bronze relief art, which has rarely survived.

- The lid was a hammered bronze sheet, weighing 13.8kg and shaped to fit the krater's opening. It is concave and perforated by multiple holes, probably because it also served as a strainer for purifying wine. A protrusion at its centre supports a 19cm statuette of moulded bronze, depicting a woman with one outstretched arm, which once may have held some object. She wears a peplos, the body-length Ancient Greek garment worn by women, and her head is covered by a veil. The statuette appears of a somewhat older style than figures on the rest of the vessel.

Significance

The enormous variety of apparently Mediterranean imports indicates wide-ranging trade connections; in particular, the Mediterranean material might have come to Vix with Greek or Etruscan traders. The wealth of imported luxury goods at Vix is, so far, unique in La Tène Europe. It has been suggested that the krater, the largest known Greek bronze vessel, should be seen in a context of high-status gift exchange connected with the trade of wine from the Mediterranean for raw materials from northern Europe.

Exhibition and reconstruction

A reconstruction of the grave and the original finds are on display in the museum at Châtillon-sur-Seine.[5]

Further tumuli

Apart from this woman's grave (mound I), there are five further known large burial mounds in the area. Three of them have been excavated so far.

- Mound II had a diameter of 33 m; its central chamber contained an urn with cremated human remains, dated by accompanying finds to c. 850 BC.

- The mound of La Butte probably dates to the mid-sixth century. As in its famous neighbouring grave, it contained a woman laid in a cart, or chariot, accompanied by two iron axes and a gold bracelet.

- A third mound, at La Garenne, was destroyed in 1846. It, too, contained a cart, as well as an Etruscan bronze bowl with four griffin or lioness handles. It is not known whether it contained skeletal remains.

Statues

In 1994, fragments of two stone statues, a warrior, and a figure of a woman, were discovered in a small enclosure.

Significance and historical role

In the area, as elsewhere in Central and Western Europe, the early Iron Age led to changes in social organisation, including a marked tendency toward the development of social hierarchies. Whereas large open settlements previously had served as central places, smaller enclosed settlements developed, often in locally prominent locations (so called manors or princely sites). They probably housed an aristocracy that had developed in the context of the increasingly important trade in iron ore and iron. Whether they really were "princesses" or "princes" in a modern sense (i.e., a noble or religious aristocracy) or simply represented an economic or mercantile elite is still the subject of much discussion. In any case, the changed social conditions also were represented by richly equipped graves which are in sharp contrast to the preceding habit of uniform simple urn burials.

Several so-called Fürstensitze (a German term describing such sites, literally "princely seats") are known from Late Hallstatt and Early La Tène Europe, for example, the burials at Hochdorf and Magdalenenberg, the Heuneburg settlement and the Glauberg settlement and burial complex. They are suggested to indicate an increasing hierarchisation of society, with these sites representing the top level, an upper class that lived removed from the majority of the population, and engaged in different social and burial habits to stress its own status.

This separation was based on economic success, connected with the trade of the new dominant metal, namely iron. Iron ores were far more widespread than the rarer materials needed to produce the previously dominant bronze: copper, but especially, tin. Thus, economic success ceased to be determined simply by access to the raw materials, but started to depend on infrastructure and trade.

The increasing economic surplus in well-situated places was invested in representative settlements (and fortifications), jewellery, and expensive imported luxury materials, a differentiation not previously possible. These changes continued even after the end of life. The new social class was not buried in egalitarian urns without much accompanying material, but received individual and elaborate burial mounds as well as rich grave offerings.

See also

References

- ↑ Vix-Musée-du-Pays-Châtillonnais: Trésor-de-Vix

- ↑ Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft "Early centralization and urbanization processes - On the Genesis and Development 'Early Celtic Princely Seats' : Mont Lassois

- ↑ Archéologie en Bourgogne: Vix (CÔTE-D’OR), Une Résidence Princière Au Temps De La Splendeur D’Athènes 2011

- ↑ Archéologie en Bourgogne: Vix (CÔTE-D’OR), Une Résidence Princière Au Temps De La Splendeur D’Athènes 2011

- ↑ Vix-Musée-du-Pays-Châtillonnais: Trésor-de-Vix

Bibliography

- René Joffroy : Le Trésor de Vix (Côte d’Or). Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1954.

- René Joffroy: Das Oppidum Mont Lassois, Gemeinde Vix, Dép Côte-d’Or. In: Germania 32, 1954, pp. 59-65.

- René Joffroy: L’Oppidum de Vix et la civilisation Hallstattienne finale dans l’Est de la France. Paris 1960.

- René Joffroy: Le Trésor de Vix. Histoire et portée d’une grande découverte. Fayard, Paris 1962.

- René Joffroy: Vix et ses trésors. Tallandier, Paris 1979.

- Franz Fischer: Frühkeltische Fürstengräber in Mitteleuropa. Antike Welt 13, Sondernummer. Raggi-Verl., Feldmeilen/Freiburg. 1982.

- Bruno Chaume: Vix et son territoire à l’Age du fer: fouilles du mont Lassois et environnement du site princier. Montagnac 2001, ISBN 2-907303-47-3.

- Bruno Chaume, Walter Reinhard: Fürstensitze westlich des Rheins, in: Archäologie in Deutschland 1, 2002, pp. 9–14.

- Claude Rolley (ed.): La tombe princière de Vix, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-7084-0697-3

- Vix, le cinquantenaire d’une découverte. Dossier d’Archéologie N° 284, Juin 2003.

- Bruno Chaume/Tamara Grübel et al.: Vix/Le mont Lassois. Recherches récentes sur le complexe aristocratique. In: Bourgogne, du Paléolithique au Moyen Âge, Dossiers d’Archéologie N° Hors Série 11, Dijon 2004, pp. 30-37.

Coordinates: 47°54′23″N 04°31′58″E / 47.90639°N 4.53278°E