Vsevolod Meyerhold

| Vsevolod Meyerhold | |

|---|---|

|

Meyerhold preparing for the role of Treplev for the Moscow Art Theater 1898 production of The Seagull by Anton Chekhov | |

| Born |

9 February [O.S. 28 January] 1874 Penza Oblast, Russian Empire |

| Died |

2 February 1940 (aged 65) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Education | Moscow Art Theatre |

| Known for | Theatre Director |

| Movement | Symbolism, Futurism |

| Spouse(s) |

Olga Munt Zinaida Reich |

| Patron(s) | Vera Komissarzhevskaya |

Vsevolod Emilevich Meyerhold (Russian: Все́волод Эми́льевич Мейерхо́льд; born German: Karl Kasimir Theodor Meiergold; 9 February [O.S. 28 January] 1874 – 2 February 1940) was a Russian and Soviet theatre director, actor and theatrical producer. His provocative experiments dealing with physical being and symbolism in an unconventional theatre setting made him one of the seminal forces in modern international theatre. During the Great Purge, Meyerhold was arrested, tortured and executed in February 1940.

Life and work

Early life

Vsevolod Meyerhold was born Karl Kasimir Theodor Meiergold in Penza on 28 January o.s. (9 February n.s.) 1874 to Russian-German wine manufacturer Emil Fyodorovich Meiergold, and his Russian-Dutch wife, Alvina Danilovna (née van der Neese).[1] He was the youngest of eight children.[2]

After completing school in 1895, Meiergold studied law at Moscow University but never completed his degree. He was torn between studying theatre or a career as a violinist. However, he failed his audition to become the second violinist in the University orchestra and in 1896 joined the Moscow Philharmonic Dramatic School.[2]

On his 21st birthday, he converted from Lutheranism to Orthodox Christianity and accepted "Vsevolod" as an Orthodox Christian name (after the Russian writer Vsevolod Garshin, whose prose Meyerhold loved).

Career

Meyerhold began acting in 1896 as a student of the Moscow Philharmonic Dramatic School under the guidance of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, co-founder of the Moscow Art Theatre. At the MAT, Meyerhold played 18 roles, such as Vasiliy Shuiskiy in Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich and Ivan the Terrible in The Death of Ivan the Terrible (both by Aleksey Tolstoy), and Treplev in Chekhov's The Seagull.

After leaving the MAT in 1902, Meyerhold participated in a number of theatrical projects, as both a director and actor. Each project was an arena for experiment and creation of new staging methods. Meyerhold was one of the most fervent advocates of Symbolism in theatre, especially when he worked as the chief producer of the Vera Komissarzhevskaya theatre in 1906–1907. He was invited back to the MAT around this time to pursue his experimental ideas.

Meyerhold continued theatrical innovation during the decade 1907–1917, while working with the imperial theatres in St. Petersburg. He introduced classical plays in an innovative manner, and staged works of controversial contemporary authors like Fyodor Sologub, Zinaida Gippius, and Alexander Blok. In these plays, Meyerhold tried to return acting to the traditions of Commedia dell'arte, rethinking them for the contemporary theatrical reality. His theoretical concepts of the "conditional theatre" were elaborated in his book On Theatre in 1913.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 made Meyerhold one of the most enthusiastic activists of the new Soviet Theatre. He joined the Bolshevik Party in 1918 and became an official of the Theatre Division (TEO) of the Commissariat of Education and Enlightenment. In 1918–1919, Meyerhold formed an alliance with Olga Kameneva, the head of the Division. Together, they tried to radicalize Russian theatres, effectively nationalizing them under Bolshevik control. Meyerhold came down with tuberculosis in May 1919 and had to leave for the south. In his absence, the head of the Commissariat, Anatoly Lunacharsky, secured Vladimir Lenin's permission to revise government policy in favor of more traditional theatres and dismissed Kameneva in June 1919.[3]

After returning to Moscow, Meyerhold founded his own theatre in 1920, which was known from 1923 as the Meyerhold Theatre until 1938. Meyerhold confronted the principles of theatrical academism, claiming that they are incapable of finding a common language with the new reality. Meyerhold’s methods of scenic constructivism and circus-style effects were used in his most successful works of the time. Some of these works included Nikolai Erdman's The Mandate, Vladimir Mayakovsky’s Mystery-Bouffe, Fernand Crommelynck's Le Cocu magnifique (The Magnanimous Cuckold) and Aleksandr Sukhovo-Kobylin's Tarelkin's Death. Mayakovsky collaborated with Meyerhold several times, and was said to have written The Bedbug especially for him; Meyerhold continued to stage Mayakovsky's productions even after the latter's suicide. The actors participating in Meyerhold’s productions acted according to the principle of biomechanics (only distantly related to the present scientific use of the term), the system of actor training that was later taught in a special school created by Meyerhold.

Meyerhold gave initial boosts to the stage careers of some of the most distinguished comic actors of the USSR, including Sergey Martinson, Igor Ilyinsky and Erast Garin. His landmark production of Nikolai Gogol's The Government Inspector (1926) was described as the following:

"Energetic, mischievous, charming Ilyinsky left his post to the nervous, fragile, suddenly freezing, grotesquely anxious Garin. Energy was replaced by trance, the dynamic with the static, happy jesting humour with bitter and glum satire".[4]

Meyerhold also gave a start to his one time assistant of "The Queen of Spades" Matvey Dubrovin, who later created his own theater in Leningrad.

Meyerhold's acting technique had fundamental principles at odds with the American method actor's conception. While method acting melded the character with the actor's own personal memories to create the character’s internal motivation, Meyerhold connected psychological and physiological processes. He had actors focus on learning gestures and movements as a way of expressing emotion physically. Following Konstantin Stanislavsky's lead, he said that the emotional state of an actor was inextricably linked to his physical state (and vice versa), and that one could call up emotions in performance by practicing and assuming poses, gestures, and movements. He developed a number of body expressions that his actors would use to portray specific emotions and characters. (Stanislavsky was also at odds with it, because like Meyerhold, his approach was psychophysical.)

Meyerhold inspired revolutionary artists and filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein, who studied with Meyerhold. In his films, Eisenstein used actors who worked in Meyerhold’s tradition. He also cast actors based on what they looked like and their expression, and followed Meyerhold's stylized acting methods. In Strike, for instance, the bourgeois are always obese, drinking, eating, and smoking, whereas the workers are more athletic.

Meyerhold was strongly opposed to socialist realism. In the early 1930s, when Joseph Stalin repressed all avant-garde art and experimentation, his works were proclaimed antagonistic and alien to the Soviet people. His theatre was closed down in January 1938; the ailing Stanislavsky, then the director of an opera theatre now known as Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre, invited Meyerhold to lead his company. Stanislavsky died in August 1938.

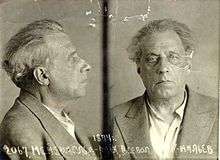

Arrest and death

Meyerhold directed his theatre for nearly a year until his arrest in Leningrad on 20 June 1939. Shortly after that, on 15 July, his wife, the actress Zinaida Reich, was found dying of exsanguination after being brutally stabbed by unknown intruders in her Moscow apartment. Later that year Meyerhold was brutally tortured[5] and forced to confess that he worked for Japanese and British intelligence agencies. He later recanted the confession in a letter to Vyacheslav Molotov.

The file on Meyerhold contains his letter from prison to Molotov:

| “ | The investigators began to use force on me, a sick 65-year-old man. I was made to lie face down and beaten on the soles of my feet and my spine with a rubber strap... For the next few days, when those parts of my legs were covered with extensive internal hemorrhaging, they again beat the red-blue-and-yellow bruises with the strap and the pain was so intense that it felt as if boiling water was being poured on these sensitive areas. I howled and wept from the pain ... When I lay down on the cot and fell asleep, after 18 hours of interrogation, in order to go back in an hour's time for more, I was woken up by my own groaning and because I was jerking about like a patient in the last stages of typhoid fever.[6] | ” |

He was sentenced to death by firing squad on 1 February 1940, and executed the next day. The Soviet government cleared him of all charges in 1955, during the first wave of de-Stalinization.

Marriage and family

Meyerhold married his first wife, Olga Munt, in 1896 and together they had three daughters. He later met the actress Zinaida Reich when she began studying with him. They fell in love and he divorced his wife; Reich was already divorced and had two children of her own. They married in 1922 or 1924.

Bibliography

In English:

Texts by Meyerhold

- Meyerhold on Theatre, trans. and ed. by Edward Braun, with a critical commentary, 1969. London: Methuen and New York: Hill and Wang.

- Meyerhold Speaks/Meyerhold Rehearses (Russian Theatre Archive), by V. Meyerhold, Alexander Gladkov (ed.) and Alma Law (ed.), Routledge, 1996

- Meyerhold at Work, Paul Schmidt (ed.), Applause Theatre Book Publishers, 1996

Works on Meyerhold

- Vsevolod Meyerhold (Routledge Performance Practitioners Series), by Jonathan Pitches, Routledge, 2003

- Meyerhold: The art of conscious theater, by Marjorie L Hoover, University of Massachusetts Press, 1974 (biography)

- Vsevolod Meyerhold (Directors in Perspective Series), by Robert Leach, Christopher Innes (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1993

- Meyerhold’s Theatre of the Grotesque: Post-revolutionary Productions, 1920–32, James M. Symons, 1971

- Meyerhold: A Revolution in Theatre, by Edward Braun, University of Iowa Press, 1998

- The Theatre of Meyerhold: Revolution and the Modern Stage by Edward Braun, 1995

- Stanislavsky and Meyerhold (Stage and Screen Studies, v. 3), by Robert Leach, Peter Lang, 2003

- Meyerhold the Director, by Konstantin Rudnitsky, Ardis, 1981

- Meyerhold, Eisenstein and Biomechanics: Actor Training in Revolutionary Russia by Alma H. Law, Mel Gordon, McFarland & co, 1995

- The Death of Meyerhold A play by Mark Jackson, premiered at The Shotgun Players, Berkeley, CA, December 2003.

- The Theater of Meyerhold and Brecht, by Katherine B. Eaton, Greenwood Press,1985

- Meyerhold and the Music Theater, by Isaak Glikman, 'Soviet Composer', Leningrad, 1989

- Vsevolod Meyerhold Annotated Bibliography, by David Roy, LTScotland, 2002

- Stanislavsky in Practice: Actor Training in Post-Soviet Russia (Artists & Issues in the Theatre, Vol. 16) by Vreneli Farber, Peter Lang, 2008 (Meyerhold's ideas applied in post-Soviet actor training)

Legacy

Center of Theatrical Arts «House of Meyerhold» at Penza

See also

- Nikolay Okhlopkov

- Michael Chekhov

- Yevgeny Vakhtangov

- Sergei Mikhailovich Tretyakov

- Andrei Droznin

- List of theatre directors

Notes

- ↑ Edward Braun (1998). Meyerhold: a Revolution in Theatre. A & C Black. p. 5. ISBN 9781408148808.

- 1 2 Pitches (2003, pg. 4)

- ↑ See Robert Leach and Victor Borovsky. A History of Russian Theatre, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-43220-0 p. 303.

- ↑ Konstantin L. Rudnitsky. Meyerhold the Director. Moscow, 1969.

- ↑ Simon Sebag Montefiore. Stalin: The court of the Red Tsar (2004), p. 323

- ↑ From letter to V. Molotov, 13 January 1940.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vsevolod Meyerhold. |

- Meyerhold's Boris Godunov

- Meyerhold in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Meyerhold Memorial Museum

- Meyerhold's theatrical system

- Meyerhold's Biomechanics, Etudes, Training

- Theatre Biomechanics as a Rehearsal Method

- Meyerhold's biomechanics

- Oliver M. Sayler article on Meyerhold's theatre

- Meyerhold on russiandrama.net

- Moscow Meyerhold Theatre (Russian)

- Meyerhold and Henri Barbusse

- Meyerhold & Mayakovsky – Biomechanics & the Communist Utopia

- Meyerhold in Russian periodicals