Wavenumber

In the physical sciences, the wavenumber (also wave number) is the spatial frequency of a wave, either in cycles per unit distance or radians per unit distance. It can be envisaged as the number of waves that exist over a specified distance (analogous to frequency being the number of cycles or radians per unit time).

In multidimensional systems, the wavenumber is the magnitude of the wave vector. The space of wave vectors is called reciprocal space. Wave numbers and wave vectors play an essential role in optics and the physics of wave scattering, such as X-ray diffraction, neutron diffraction, and elementary particle physics.

For quantum mechanical waves, wavenumber multiplied by Planck's constant is the canonical momentum.

Wavenumber can be used to specify quantities other than spatial frequency. In optical spectroscopy, it is often used as a unit of temporal frequency assuming a certain speed of light. In this context, it is the number of cycles—not radians—per unit length, usually one centimeter. In the same domain, wavenumber can also be used as a unit of energy; 1 cm−1 of energy is the amount of energy in a single photon with a wavelength of 1 cm, the conversion being done using Planck's relation. For example, 1 cm−1 implies 1.23984×10−4 eV, and 8065.54 cm−1 implies 1 eV.[1]

Definition

It can be defined as either:

- , the number of wavelengths per unit distance, where λ is the wavelength, sometimes termed the spectroscopic wavenumber, or

- , the number of radians per unit distance, sometimes termed the angular wavenumber or circular wavenumber, but more often simply wavenumber.

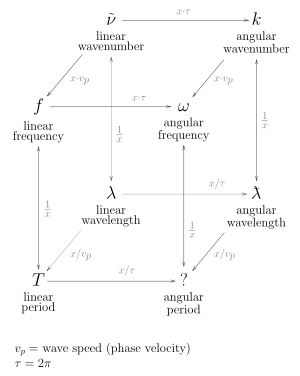

There are four total symbols for wavenumber. Under the first definition ν, , or σ may be used; for the second, k should be used.

When wavenumber is represented by the symbol ν, a frequency is still being represented, albeit indirectly. As described in the spectroscopy section, this is done through the relationship , where νs is a frequency in hertz. This is done for convenience as frequencies tend to be very large. [2]

It has dimensions of reciprocal length, so its SI unit is the reciprocal of meters (m−1). In spectroscopy it is usual to give wavenumbers in cgs unit, i.e., reciprocal centimeters (cm−1); in this context the wavenumber was formerly called the Kayser, after Heinrich Kayser (some older scientific papers used this unit, abbreviated as K, where 1 K = 1 cm−1).[3] The angular wavenumber may be expressed in radians per meter (rad·m−1), or as above, since the radian is dimensionless.

For electromagnetic radiation in vacuum, wavenumber is proportional to frequency and to photon energy. Because of this, wavenumbers are used as a unit of energy in spectroscopy.

Complex

A complex-valued wavenumber can be defined for a medium with complex-valued permittivity ε, permeability μ0 and refraction index n as:[4]

where k0 is the free-space wavenumber, as above.

In wave equations

Here we assume that the wave is regular in the sense that the different quantities describing the wave such as the wavelength, frequency and thus the wavenumber are constants. See wavepacket for discussion of the case when these quantities are not constant.

In general, the angular wavenumber (i.e. the magnitude of the wave vector) is given by

where is the frequency of the wave, is the wavelength, is the angular frequency of the wave, and is the phase velocity of the wave. The dependence of the wavenumber on the frequency (or more commonly the frequency on the wavenumber) is known as a dispersion relation.

For the special case of an electromagnetic wave in vacuum, where vp = c, k is given by

where E is the energy of the wave, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, and c is the speed of light in a vacuum.

For the special case of a matter wave, for example an electron wave, in the non-relativistic approximation (in the case of a free particle, that is, the particle has no potential energy):

Here p is the momentum of the particle, m is the mass of the particle, E is the kinetic energy of the particle, and ħ is the reduced Planck's constant.

Wavenumber is also used to define the group velocity.

In spectroscopy

In spectroscopy, "wavenumber" often refers to a frequency (temporal frequency), but which has been divided by the speed of light in vacuum:

The historical reason for using this spectroscopic wavenumber rather than frequency is that it proved to be convenient in the measurement of atomic spectra: the spectroscopic wavenumber is the reciprocal of the wavelength of light in vacuum:

which remains essentially the same in air, and so the spectroscopic wavenumber is directly related to the angles of light scattered from diffraction gratings and the distance between fringes in interferometers, when those instruments are operated in air or vacuum. Such wavenumbers were first used in the calculations of Johannes Rydberg in the 1880s. The Rydberg–Ritz combination principle of 1908 was also formulated in terms of wavenumbers. A few years later spectral lines could be understood in quantum theory as differences between energy levels, energy being proportional to wavenumber, or frequency. However, spectroscopic data kept being tabulated in terms of spectroscopic wavenumber rather than frequency or energy.

For example, the spectroscopic wavenumbers of the emission spectrum of atomic hydrogen are given by the Rydberg formula:

where R is the Rydberg constant, and ni and nf are the principal quantum numbers of the initial and final levels respectively (ni is greater than nf for emission).

A spectroscopic wavenumber can be converted into energy per photon E by Planck's relation:

It can also be converted into wavelength of light:

where n is the refractive index of the medium. Note that the wavelength of light changes as it passes through different media, however, the spectroscopic wavenumber (i.e., frequency) remains constant.

Conventionally, inverse centimeter (cm−1) units are used for , so often that such spatial frequencies are stated by some authors "in wavenumbers",[5] incorrectly transferring the name of the quantity to the CGS unit cm−1 itself.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ NIST Reference on Constants, Units and Uncertainty (CODATA 2010), specifically 100/m and 1 eV. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Wave number". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Murthy, V. L. R.; Lakshman, S. V. J. (1981). "Electronic absorption spectrum of cobalt antipyrine complex". Solid State Communications. 38 (7): 651–652. doi:10.1016/0038-1098(81)90960-1.

- ↑ , eq.(2.13.3)

- ↑ See for example,

- Fiechtner, G. (2001). "Absorption and the dimensionless overlap integral for two-photon excitation". Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer. 68 (5): 543. Bibcode:2001JQSRT..68..543F. doi:10.1016/S0022-4073(00)00044-3.

- US 5046846, Ray, James C. & Asari, Logan R., "Method and apparatus for spectroscopic comparison of compositions", published 1991-09-10

- "Boson Peaks and Glass Formation". Science. 308 (5726): 1221. 2005. doi:10.1126/science.308.5726.1221a.

- ↑ Hollas, J. Michael (2004). Modern spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons. p. xxii. ISBN 0470844159.