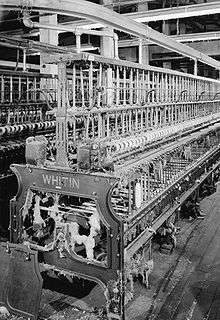

Whitin Machine Works

The Whitin Machine Works (WMW) was founded by Paul Whitin and his sons in 1831 on the banks of the Mumford River in South Northbridge, Massachusetts. The village of South Northbridge became known as Whitinsville in 1835, in honor of its founder.

The WMW became one of the largest textile machinery companies in the world. Known as The "Shop" to locals, would operate well into the 20th century, long after many of the New England mills had moved South. By 1948, The company was operating at peak capacity, employing 5,615 men and women. The Shop was the center of life in the village of Whitinsville, Massachusetts for over 135 years, until 1976.

Origins

In 1809, Paul Whitin and his father-in-law James Fletcher and others from Northbridge and Leicester, established the Northbridge Cotton Manufacturing Company. This wood-framed spinning mill, two and one-half stories high had 200 spindles and was only the third cotton mill in the Blackstone Valley at the time.

In 1815, Paul Whitin became a partner with Fletcher, and his two brothers-in-law, Samuel and Ezra Fletcher, under the firm name of Whitin and Fletcher. Then they built a second mill with 300 spindles on the opposite side of the Mumford River. Paul Whitin then bought out the Fletcher shares in 1826 and formed a new partnership with his two sons, Paul Jr. and John Crane Whitin. The new company was called Paul Whitin and Sons.[1] Also in 1826, a new brick mill was constructed, having 2000 spindles, which still stands today at Whitinsville, having been recently restored.

The 1826 brick mill is perhaps the oldest surviving, unaltered textile mill remaining in Massachusetts. Colonel Fletcher's 1772 Blacksmith Forge is also still standing, next to the Brick Mill, on the west bank of the Mumford River.

Later on, Paul Whitin's two other younger sons, Charles P. and James F. later also entered into the family-run business.

Whitin would die in 1831. Years later, with the cotton business on a solid basis and escalating in 1845, Betsey Whitin and her sons built a new, stone textile factory, largely of granite known as the Whitinsville Cotton Mill, which gave the family business 7,500 more spindles. The Whitinsville Cotton Mill would later be used as a testing facility for new equipment developed by the Whitin Machine Works, across the street. This is now called the restored Cotton Mill Apartments, in Whitinsville.

Whitinsville: a company town

In 1831, Paul Whitin's third son John Crane Whitin designed and had patented a new cotton picker machine that outperformed others in the previous mills. This was to be first of other successive inventions that would establish the Whitin Machine Works as a great textile machinery company.

In 1847, the Whitins built "The Shop," which consisted of a new textile production area that was four times larger than the brick mill. It contained machine shops, foundries, and other specialized structures.

As the family textile businesses expanded, so did the village of Whitinsville. More housing was provided by the company for new workers on North Main St. and on other side streets as Irish workers poured into the labor pool that same year (1847). Just seven years prior, John C. Whitin had developed the first of stately mansions, which had occupied land where the Whitin Gymnasium now stands. During this time also, Paul Whitin Jr. had married Sarah Chapin and built a new Italian-styled home, along with his brother in 1856.

Life in the village revolved around "the shop," providing the means and the opportunity for successive generations of mostly Europeans to immigrate. The Whitin's built the entire village to support their expanding business operations. In all the company would erect 1,000 buildings (2200 units) to house their growing workforce. The work was hard and often dangerous. There were recorded incidents where workers lost their lives working in the shop foundry or the machine shop. But working and living in Whitinsville was much better than the average mill town. "The company" provided amenities unheard of in neighboring villages; such as heating coal at company cost, free snowplowing, landscaping and property maintenance. The Whitin's allowed any employee who heated their homes with wood access to their properties to cut down as many trees as needed, free of charge. The company constructed the first reservoir, creating meadow pond, (west of Main St.) which was the first system that pumped water directly into village homes. A typical sight on weekends would be the villager's sailing and fishing on the pond using equipment rented from the company provided facility. Through the 1860s the work schedule was 11 hours (7am-6pm) per day and 6 days per week. And yet, there was a long-standing tradition of allowing up to 4 unpaid personal days off per month. It is well known, for instance, that during slow times in the shop, John C. would hire idle employees to work on his property, farms, or, as in 1879, build the Town Hall as a memorial to his late father and mother. As the fortunes of the company grew, so would its generosity to the town. Many public buildings still in use today were built with Whitin funds and then donated to the town; the Whitin Community Center being a prime example.

The Whitin family continued to hold the Whitin Machine Works privately until 1946. By 1948, the company was operating at peak capacity, employing 5,615 men and women. Its products were sold worldwide. However, the business declined over the next two decades. In 1966, Whitin Machine Works was sold to White Consolidated Industries. The plant would struggle along for another decade, when in 1976 the facility was shut up.[2]

Today

Referred to as "The Shop" in Whitinsville, for more than fifteen years, the massive facility converted into a complex that has been replaced with 26 different businesses employing approximately 2,000 people.

See also

References

External links

- Northbridge History-Articles by Don Gosselin

- Whitin Mill Restoration

- A Guide to the Blackstone Valley

- Vintage Whitin Catalog Images

- Whitin Machine Works Records at Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School