Wieliczka

| Wieliczka | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

|

Park in Wieliczka with church in background | ||

| ||

Wieliczka | ||

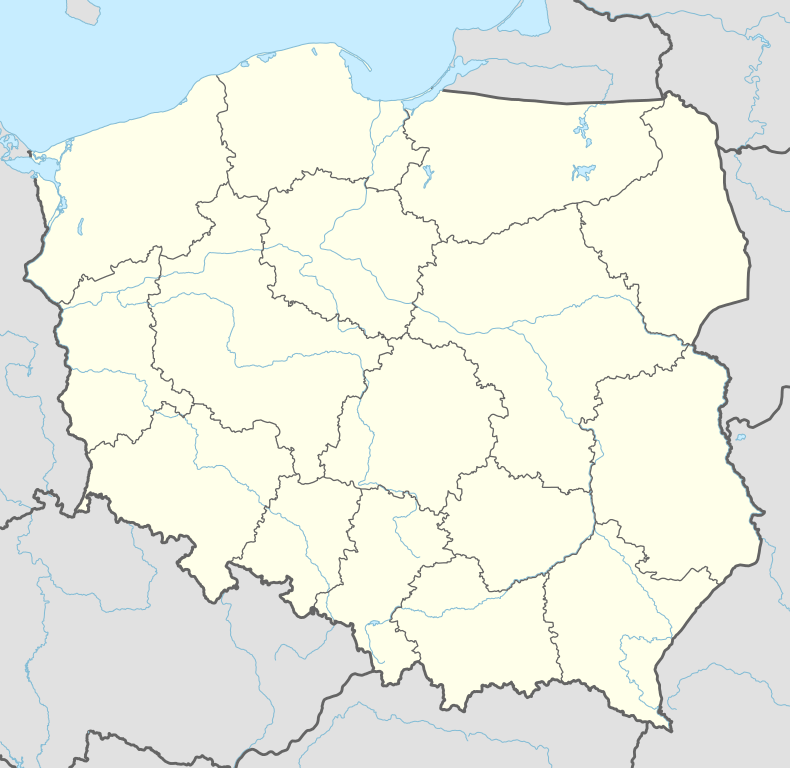

| Coordinates: 49°59′22″N 20°3′58″E / 49.98944°N 20.06611°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Voivodeship | Lesser Poland | |

| County | Wieliczka County | |

| Gmina | Gmina Wieliczka | |

| Established | 1123-1127 | |

| Town rights | 1290 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Artur Kozioł | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 13.41 km2 (5.18 sq mi) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 20,075 | |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,900/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 32-020 | |

| Area code(s) | +48 12 | |

| Car plates | KWI | |

| Website | http://www.wieliczka.gmina.pl | |

Wieliczka [vʲɛˈlʲit͡ʂka] is a town (2006 population: 19,128) in southern Poland in the Kraków metropolitan area, and situated (since 1999) in Lesser Poland Voivodeship; previously, it was in Kraków Voivodeship (1975–1998). The town was founded in 1290 by Duke Premislas II of Poland.

Geographic location

The city of Wieliczka lies in the south central part of Poland, within the Małopolska region, in the Kraków area. The city is located 13 km (8.1 mi) to the southeast of Kraków. Under the town is the Wieliczka Salt Mine – one of the world's oldest operating salt mines (the oldest is at Bochnia, Poland, 20 km (12 mi) from Wieliczka), which has been in operation since prehistoric times.[1]

The town lies in a valley between two ridges that stretch from west to east: south Wieliczka foothills, north Bogucice sands, including the Wieliczka-Gdów Upland. The south ridge is higher, while the northern ridge leads to national road 94. Near the town lies the A4 highway (E40 European route), which in the near future will connect Kraków to Ukraine. Despite the small area, the city's relative altitude accounts for more than 137 –m–: the highest mountain reaches 361,8 metres above the sea, and the lowest point lies at an altitude of 224 metres above sea level.

Culture

Wieliczka, as well as the nearby village of Lednica Górna are among the last places in Poland where the Easter tradition of Siuda Baba is still practised.[2][3]

History

Medieval times

The first settlers were probably from the Celtic tribes. In later years they were driven out by the Slavic population. The importance of mining deposits arose after the capital of Poland was moved from Gniezno to Kraków by Casimir I the Restorer. Brewing brought huge revenues, which the prince needed to maintain the court and rebuild the destroyed country. Systematic development of the mining settlement stopped the Tartar invasion, which destroyed Kraków and surroundings.

After the 1252 discovery of salt and potassium deposits extraction of salt from deep regions in the earth began. In the year 1289, Henryk IV Probus, then Lord of Kraków issued a document authorising the brothers Jeskowi and Hysinboldowi to rule the town of Wieliczka. The next year Duke Przemysł II gave Wieliczka town privileges and in 1311, during the reign of Władysław Łokietek, then General Secretary of Geslar de Kulpen joined the Rebellion of wójt Albert. After terminating the rebellion Albert fled to Silesia, where he served as Steward of Wieliczka.

17th to 18th century

In 1651 the Wieliczka population was decimated by a plague. In the years 1655-1660, at the time of the Swedish invasion, the city was in economic decline. The mine was plundered and burned by the Swedes. The Swedish crew guarded the mine and the taxes were raised upon the population. Gabriel Wojniłłowicz alongside with Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski proceeded to organize approximately 3,000 people which took part in the liberation of Wieliczka, Bochnia and Wiśnicz. The battle took place in Kamionna, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, where the Poles attacked the hill, and referred their victory.

18th to 19th century

On 9 June 1772 the occupation of Wieliczka by the forces of the Austrian began. In 1809 Wieliczka was incorporated into the Duchy of Warsaw by the Austrians and so the Habsburgs regained the city after the fall of the Duchy and its partition by the Congress of Vienna. From then on the official German name Groß Salz became part of Galicia. In the time of the partition, unemployment arose because the Austrians brought modern equipment which caused a cease of production throughout the city and surrounding areas, due to low wages, forcing were dismiss en masse of Polish miners. That led to the arrival of German, Hungarian, Croatian and Transylvanian miners, changing so the ethnic composition of the city in favor of the immigrant population. After the outbreak of the uprising in 1846 in Kraków by Edward Dembowski, who became Secretary to Jan Tyssowski, the dictator of the revolution, the miners seized power in the Wieliczka salt mine. In the period of Galician autonomy there was a gradual development of the city. The mine became the largest in concentration of miners in Galicia. In the Nitra district, there were over 2000 workers employed.

20th to 21st century

Only by the end of the nineteenth century there was public housing development. The city expanded with private money, mining built colonies (settlement for families of mining workers), a salinarną power plant (supplied electricity not only to the mine, but also to the city). In the inter-war period, Wieliczkaites saw the development of territorial area, new residential districts were formed until a 1933 miners' strike took place, due to the reduction of wages by 13%.

On 7 September 1939 began the occupation of Poland by the German army, which entered the country through Slovakia. The city was crowded, as Wieliczka moved approximately 5.4 thousand people of Jewish origin to Kraków after the opening of the ghetto. On 21 January 1945 the Soviet army invaded Wieliczka. After World War II, began a period of systematic development of the city. In 1978 UNESCO decided to list Wielicką salt mine as a world cultural heritage. In 1994 the city was declared a historical monument.

Sport

- Górnik Wieliczka - football club

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Bergkamen, Germany[4][5]

Bergkamen, Germany[4][5] Saint-Andre-lez-Lille, France[4]

Saint-Andre-lez-Lille, France[4] Sesto Fiorentino, Italy[4]

Sesto Fiorentino, Italy[4] Litovel, Czech Republic[4]

Litovel, Czech Republic[4]

Notable residents

The painter Esther Hamerman was born in Wieliczka, only to eventually move to Vienna.[6]

Gallery

| Downtown Wieliczka and Panorama | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- ↑ Jerzy Grzesiowski, Wieliczka: kopalnia, muzeum, zamek (Wieliczka: the Mine, the Museum, the Castle), 2nd ed., updated and augmented, Warsaw, Sport i Turystyka, 1987, ISBN 83-217-2637-2.

- ↑ Barbara Ogrodowska, Zwyczaje, obrzędy i tradycje w Polsce. Warsaw: Verbinum, 2001, p. 190.

- ↑ Julian Zinkow, Krakowskie podania, legendy i zwyczaje (oraz wybór podań i legend jurajskich). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Platan, 2004, p. 216-218

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Wieliczka Miasta partnerskie" [Polish]. Urząd Miasta i Gminy Wieliczka. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ "List of Twin Towns in the Ruhr District". Twins2010.com. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ Newhall, Edith. "All in the Family". Artnews. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Attribution

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wieliczka". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wieliczka". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wieliczka. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Wieliczka. |

- Wieliczka The salt of the Earth/

- Exhibition of Technique in Wieliczka

- Wieliczka County page

- Wieliczka on Interactive map of Kraków

- Jewish Community in Wieliczka on Virtual Shtetl

- See Virtual Tour Virtually visit the Franciscan Monastery

Coordinates: 49°59′N 20°04′E / 49.983°N 20.067°E