William Makepeace Thackeray

| William Makepeace Thackeray | |

|---|---|

1855 daguerreotype of William Makepeace Thackeray | |

| Born |

18 July 1811 Calcutta, British India |

| Died |

24 December 1863 (aged 52) London, England, UK |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | 1829–1864 (published posthumously) |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Notable works | Vanity Fair |

| Spouse | Isabella Gethin Shawe |

| Children |

|

William Makepeace Thackeray (/ˈθækəri/; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist of the 19th century. He is known for his satirical works, particularly Vanity Fair, a panoramic portrait of English society.

Biography

Thackeray, an only child, was born in Calcutta,[1] British India, where his father, Richmond Thackeray (1 September 1781 – 13 September 1815), was secretary to the Board of Revenue in the British East India Company. His mother, Anne Becher (1792–1864), was the second daughter of Harriet Becher and John Harman Becher, who was also a secretary (writer) for the East India Company.

Richmond died in 1815, which caused Anne to send her son to England in 1816, while she remained in British India. The ship on which he travelled made a short stopover at St. Helena, where the imprisoned Napoleon was pointed out to him. Once in England he was educated at schools in Southampton and Chiswick, and then at Charterhouse School, where he became a close friend of John Leech. Thackeray disliked Charterhouse,[2] and parodied it in his fiction as "Slaughterhouse". Nevertheless, Thackeray was honoured in the Charterhouse Chapel with a monument after his death. Illness in his last year there, during which he reportedly grew to his full height of six foot three, postponed his matriculation at Trinity College, Cambridge, until February 1829. Never too keen on academic studies, Thackeray left Cambridge in 1830, but some of his earliest published writing appeared in two university periodicals, The Snob and The Gownsman.[3]

Thackeray then travelled for some time on the continent, visiting Paris and Weimar, where he met Goethe. He returned to England and began to study law at the Middle Temple, but soon gave that up. On reaching the age of 21 he came into his inheritance from his father, but he squandered much of it on gambling and on funding two unsuccessful newspapers, The National Standard and The Constitutional, for which he had hoped to write. He also lost a good part of his fortune in the collapse of two Indian banks. Forced to consider a profession to support himself, he turned first to art, which he studied in Paris, but did not pursue it, except in later years as the illustrator of some of his own novels and other writings.

Thackeray's years of semi-idleness ended after he married, on 20 August 1836, Isabella Gethin Shawe (1816–1893), second daughter of Isabella Creagh Shawe and Matthew Shawe, a colonel who had died after distinguished service, primarily in India. The Thackerays had three children, all girls: Anne Isabella (1837–1919), Jane (who died at eight months old) and Harriet Marian (1840–1875), who married Sir Leslie Stephen, editor, biographer and philosopher.

Thackeray now began "writing for his life", as he put it, turning to journalism in an effort to support his young family. He primarily worked for Fraser's Magazine, a sharp-witted and sharp-tongued conservative publication for which he produced art criticism, short fictional sketches, and two longer fictional works, Catherine and The Luck of Barry Lyndon. Between 1837 and 1840 he also reviewed books for The Times.[4] He was also a regular contributor to The Morning Chronicle and The Foreign Quarterly Review. Later, through his connection to the illustrator John Leech, he began writing for the newly created magazine Punch, in which he published The Snob Papers, later collected as The Book of Snobs. This work popularised the modern meaning of the word "snob". Thackeray was a regular contributor to Punch between 1843 and 1854.[5]

Tragedy struck in Thackeray's personal life as his wife, Isabella, succumbed to depression after the birth of their third child, in 1840. Finding that he could get no work done at home, he spent more and more time away until September 1840, when he realised how grave his wife's condition was. Struck by guilt, he set out with his wife to Ireland. During the crossing she threw herself from a water-closet into the sea, but she was pulled from the waters. They fled back home after a four-week battle with her mother. From November 1840 to February 1842 Isabella was in and out of professional care, as her condition waxed and waned.

She eventually deteriorated into a permanent state of detachment from reality. Thackeray desperately sought cures for her, but nothing worked, and she ended up in two different asylums in or near Paris until 1845, after which Thackeray took her back to England, where he installed her with a Mrs Bakewell at Camberwell. Isabella outlived her husband by 30 years, in the end being cared for by a family named Thompson in Leigh-on-Sea at Southend until her death in 1894.[6] After his wife's illness Thackeray became a de facto widower, never establishing another permanent relationship. He did pursue other women, however, in particular Mrs Jane Brookfield and Sally Baxter. In 1851 Mr Brookfield barred Thackeray from further visits to or correspondence with Jane. Baxter, an American twenty years Thackeray's junior whom he met during a lecture tour in New York City in 1852, married another man in 1855.

In the early 1840s Thackeray had some success with two travel books, The Paris Sketch Book and The Irish Sketch Book, the latter marked by hostility to Irish Catholics. However, as the book appealed to British prejudices, Thackeray was given the job of being Punch’s Irish expert, often under the pseudonym Hibernis Hibernior.[5] It was Thackeray, in other words, who was chiefly responsible for Punch's notoriously hostile and condescending depictions of the Irish during the Irish Famine (1845–51).[5]

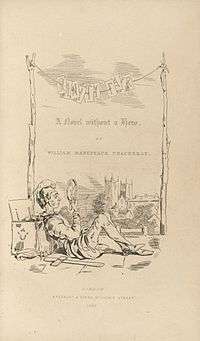

Thackeray achieved more recognition with his Snob Papers (serialised 1846/7, published in book form in 1848), but the work that really established his fame was the novel Vanity Fair, which first appeared in serialised instalments beginning in January 1847. Even before Vanity Fair completed its serial run Thackeray had become a celebrity, sought after by the very lords and ladies whom he satirised. They hailed him as the equal of Dickens.

He remained "at the top of the tree," as he put it, for the rest of his life, during which he produced several large novels, notably Pendennis, The Newcomes and The History of Henry Esmond, despite various illnesses, including a near-fatal one that struck him in 1849 in the middle of writing Pendennis. He twice visited the United States on lecture tours during this period. Thackeray also gave lectures in London on the English humorists of the eighteenth century, and on the first four Hanoverian monarchs. The latter series was published in book form as The Four Georges.

In Oxford he stood unsuccessfully as an independent for Parliament. He was narrowly beaten by Cardwell, who received 1,070 votes, as against 1,005 for Thackeray.

In 1860 Thackeray became editor of the newly established Cornhill Magazine, but he was never comfortable in the role, preferring to contribute to the magazine as the writer of a column called Roundabout Papers.

Thackeray's health worsened during the 1850s and he was plagued by a recurring stricture of the urethra that laid him up for days at a time. He also felt that he had lost much of his creative impetus. He worsened matters by excessive eating and drinking, and avoiding exercise, though he enjoyed horseback-riding (he kept a horse). He has been described as "the greatest literary glutton who ever lived". His main activity apart from writing was "guttling and gorging".[7] He could not break his addiction to spicy peppers, further ruining his digestion. On 23 December 1863, after returning from dining out and before dressing for bed, he suffered a stroke. He was found dead in his bed the following morning. His death at the age of fifty-two was entirely unexpected, and shocked his family, his friends and the reading public. An estimated 7,000 people attended his funeral at Kensington Gardens. He was buried on 29 December at Kensal Green Cemetery, and a memorial bust sculpted by Marochetti can be found in Westminster Abbey.

Works

Thackeray began as a satirist and parodist, writing works that displayed a sneaking fondness for roguish upstarts such as Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, and the title characters of The Luck of Barry Lyndon and Catherine. In his earliest works, written under such pseudonyms as Charles James Yellowplush, Michael Angelo Titmarsh and George Savage Fitz-Boodle, he tended towards savagery in his attacks on high society, military prowess, the institution of marriage and hypocrisy.

One of his earliest works, "Timbuctoo" (1829), contains a burlesque upon the subject set for the Cambridge Chancellor's Medal for English Verse (the contest was won by Tennyson with "Timbuctoo"). Thackeray's writing career really began with a series of satirical sketches now usually known as The Yellowplush Papers, which appeared in Fraser's Magazine beginning in 1837. These were adapted for BBC Radio 4 in 2009, with Adam Buxton playing Charles Yellowplush.[8]

Between May 1839 and February 1840 Fraser's published the work sometimes considered Thackeray's first novel, Catherine. Originally intended as a satire of the Newgate school of crime fiction, it ended up being more of a picaresque tale. He also began work, never finished, on the novel later published as A Shabby Genteel Story.

In The Luck of Barry Lyndon, a novel serialised in Fraser's in 1844, Thackeray explored the situation of an outsider trying to achieve status in high society, a theme he developed more successfully in Vanity Fair with the character of Becky Sharp, the artist's daughter who rises nearly to the heights by manipulating the other characters.

Thackeray is probably best known now for Vanity Fair. In contrast, his large novels from the period after Vanity Fair, which were once described by Henry James as examples of "loose baggy monsters", have largely faded from view, perhaps because they reflect a mellowing in Thackeray, who had become so successful with his satires on society that he seemed to lose his zest for attacking it. These later works include Pendennis, a Bildungsroman depicting the coming of age of Arthur Pendennis, an alter ego of Thackeray, who also features as the narrator of two later novels, The Newcomes and The Adventures of Philip. The Newcomes is noteworthy for its critical portrayal of the "marriage market," while Philip is known for its semi-autobiographical depiction of Thackeray's early life, in which he partially regains some of his early satirical power.

Also notable among the later novels is The History of Henry Esmond, in which Thackeray tried to write a novel in the style of the eighteenth century, a period that held great appeal for him. Not only Esmond but also Barry Lyndon and Catherine are set in that period, as is the sequel to Esmond, The Virginians, which takes place in North America and includes George Washington as a character who nearly kills one of the protagonists in a duel.

Family

Parents

Thackeray's father, Richmond Thackeray, was born at South Mimms and went to India in 1798 at age sixteen as a writer (civil servant) with the East India Company. Richmond fathered a daughter, Sarah Redfield, in 1804 with Charlotte Sophia Rudd, his possibly Eurasian mistress, and both mother and daughter were named in his will. Such liaisons were common among gentlemen of the East India Company, and it formed no bar to his later courting and marrying William's mother.[9]

Thackeray's mother, Anne Becher (born 1792), was "one of the reigning beauties of the day" and a daughter of John Harmon Becher, Collector of the South 24 Parganas district (d. Calcutta, 1800), of an old Bengal civilian family "noted for the tenderness of its women". Anne Becher, her sister Harriet and their widowed mother, also Harriet, had been sent back to India by her authoritarian guardian grandmother, Ann Becher, in 1809 on the Earl Howe. Anne's grandmother had told her that the man she loved, Henry Carmichael-Smyth, an ensign in the Bengal Engineers whom she met at an Assembly Ball in 1807 in Bath, had died, while he was told that Anne was no longer interested in him. Neither of these assertions was true. Though Carmichael-Smyth was from a distinguished Scottish military family, Anne's grandmother went to extreme lengths to prevent their marriage. Surviving family letters state that she wanted a better match for her granddaughter.[10]

Anne Becher and Richmond Thackeray were married in Calcutta on 13 October 1810. Their only child, William, was born on 18 July 1811.[11] There is a fine miniature portrait of Anne Becher Thackeray and William Makepeace Thackeray, aged about two, done in Madras by George Chinnery c. 1813.[12]

Anne's family's deception was unexpectedly revealed in 1812, when Richmond Thackeray unwittingly invited the supposedly dead Carmichael-Smyth to dinner. Five years later, after Richmond had died of a fever on 13 September 1815, Anne married Henry Carmichael-Smyth, on 13 March 1817. The couple moved to England in 1820, after having sent William off to school there more than three years earlier. The separation from his mother had a traumatic effect on the young Thackeray, which he discussed in his essay "On Letts's Diary" in The Roundabout Papers.

Descendants

Thackeray is an ancestor of the British financier Ryan Williams, and is the great-great-great-grandfather of the British comedian Al Murray.[13]

Reputation and legacy

During the Victorian era Thackeray was ranked second only to Charles Dickens, but he is now much less widely read and is known almost exclusively for Vanity Fair, which has become a fixture in university courses, and has been repeatedly adapted for the cinema and television.

In Thackeray's own day some commentators, such as Anthony Trollope, ranked his History of Henry Esmond as his greatest work, perhaps because it expressed Victorian values of duty and earnestness, as did some of his other later novels. It is perhaps for this reason that they have not survived as well as Vanity Fair, which satirises those values.

Thackeray saw himself as writing in the realistic tradition, and distinguished his work from the exaggerations and sentimentality of Dickens. Some later commentators have accepted this self-evaluation and seen him as a realist, but others note his inclination to use eighteenth-century narrative techniques, such as digressions and direct addresses to the reader, and argue that through them he frequently disrupts the illusion of reality. The school of Henry James, with its emphasis on maintaining that illusion, marked a break with Thackeray's techniques.

In 1887 the Royal Society of Arts unveiled a blue plaque to commemorate Thackeray at the house at 2 Palace Green, London, that had been built for him in the 1860s.[14] It is now the location of the Israeli Embassy.[15]

Thackeray's former home in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, is now a restaurant named after the author.[16]

List of works

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Makepeace Thackeray |

- The Yellowplush Papers (1837) – ISBN 0-8095-9676-8

- Catherine (1839–40) – ISBN 1-4065-0055-0 (originally credited to "Ikey Solomons, Esq. Junior"[17])

- A Shabby Genteel Story (1840) – ISBN 1-4101-0509-1

- The Irish Sketchbook (1843) – ISBN 0-86299-754-2

- The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844), filmed as Barry Lyndon by Stanley Kubrick – ISBN 0-19-283628-5

- Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Grand Cairo (1846), under the name Mr M. A. Titmarsh.

- Mrs. Perkins's Ball (1846), under the name M. A. Titmarsh

- The Book of Snobs (1848), which popularised that term- ISBN 0-8095-9672-5

- Vanity Fair (1848) – ISBN 0-14-062085-0

- Pendennis (1848–1850) – ISBN 1-4043-8659-9

- Rebecca and Rowena (1850), a parody sequel of Ivanhoe – ISBN 1-84391-018-7

- The Paris Sketchbook (1840), featuring Roger Bontemps

- Men's Wives (1852) – ISBN 978-1-77545-023-8

- The History of Henry Esmond (1852) – ISBN 0-14-143916-5

- The English Humorists of the Eighteenth Century (1853)

- The Newcomes (1855) – ISBN 0-460-87495-0

- The Rose and the Ring (1855) – ISBN 1-4043-2741-X

- The Virginians (1857–1859) – ISBN 1-4142-3952-1

- Four Georges (1860-1861) - ISBN 978-1410203007

- The Adventures of Philip (1862) – ISBN 1-4101-0510-5

- Roundabout Papers (1863)

- Denis Duval (1864) – ISBN 1-4191-1561-8

- The Orphan of Pimlico (1876)

- Sketches and Travels in London

- Stray Papers: Being Stories, Reviews, Verses, and Sketches (1821-1847)

- Literary Essays

- The English Humorists of the eighteenth century: a series of lectures (1867)

- Lovel the Widower

- Ballads

- Christmas Books

- Samuel Titmarsh

- Miscellanies

- Stories

- Burlesques

- Irish Sketchbook volume 2

- Character Sketches

- Critical Reviews

- Second Funeral of Napoleon

See also

- Anne Isabella Thackeray

- Barry Lyndon, the film adaptation by Stanley Kubrick

References

- ↑ Calcutta was the capital of the British Indian Empire at the time. Thackeray was born on the grounds of what is now the Armenian College & Philanthropic Academy, on the old Freeschool Street, now called Mirza Ghalib Street.

- ↑ Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 25.

- ↑ "Thackeray, William Makepeace (THKY826WM)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Gary Simons, "Thackeray's Contributions to the Times", Victorian Periodicals Review, 40:4 (2007, pp. 332–354

- 1 2 3 Peter Gray, "Punch and the Great Famine", History Ireland, Summer 1993)

- ↑ Ann Monsarrat, An Uneasy Victorian: Thackeray the Man, 1811–1863, London: Cassell, 1980, pp. 121, 128, 134, 161; John Aplin, Memory and Legacy: A Thackeray Family Biography, 1876-1919, Cambridge: Lutterworth, 2011, pp. 5, 136.

- ↑ Bee Wilson, "Vanity Fare", New Statesman, 27 November 1998. Retrieved 4 January 2014

- ↑ "The Yellowplush Papers". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Menon, Anil (29 March 2006). "William Makepeace Thackeray: The Indian in the Closet". Round Dice. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Alexander, Eric (2007). "Ancestry of William Thackeray". Henry Cort Father of the Iron Trade. henrycort.net. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ Gilder, Jeannette Leonard; Joseph Benson Gilder (15 May 1897). The Critic: An Illustrated Monthly Review of Literature, Art, and Life (Original from Princeton University, Digitized 18 April 2008 ed.). Good Literature Pub. Co. p. 335.

- ↑ Ooty Well Preserved & Flourishing

- ↑ Cavendish, Dominic (3 March 2007). "Prime Time, Gentlemen, Please". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "THACKERAY, WILLIAM MAKEPEACE (1811-1863)". English Heritage. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ British History website

- ↑ Thackeray's, 85 London Rd, Tunbridge Wells, TN1 1EA Bookatable. Downloaded 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Harden, Edgar (2003). A William Makepeace Thackeray Chronology. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-230-59857-7. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

Bibliography

- Catalan, Zelma. The Politics of Irony in Thackeray’s Mature Fiction: Vanity Fair, Henry Esmond, The Newcomes. Sofia (Bulgaria), 2010, 250 pр.

- Sheldon Goldfarb Catherine: A Story (The Thackeray Edition). University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Ferris, Ina. William Makepeace Thackeray. Boston: Twayne, 1983.

- Jack, Adolphus Alfred. Thackeray: A Study. London: Macmillan, 1895.

- Monsarrat, Ann. An Uneasy Victorian: Thackeray the Man, 1811–1863. London: Cassell, 1980.

- Peters, Catherine. Thackeray’s Universe: Shifting Worlds of Imagination and Reality. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Prawer, Siegbert S.: Breeches and Metaphysics: Thackeray's German Discourse. Oxford: Legenda, 1997.

- Prawer, Siegbert S.: Israel at Vanity Fair: Jews and Judaism in the Writings of W. M. Thackeray. Leiden: Brill, 1992.

- Prawer, Siegbert S.: W. M. Thackeray's European sketch books: a study of literary and graphic portraiture. P. Lang, 2000.

- Ray, Gordon N. Thackeray: The Uses of Adversity, 1811–1846. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955.

- Ray, Gordon N. Thackeray: The Age of Wisdom, 1847–1863. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1957.

- Ritchie, H.T. Thackeray and His Daughter. Harper and Brothers, 1924.

- Rodríguez Espinosa, Marcos (1998) Traducción y recepción como procesos de mediación cultural: 'Vanity Fair' en España. Málaga: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga.

- Shillingsburg, Peter. William Makepeace Thackeray: A Literary Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001.

- Bloom, Abigail Burnham; Maynard, John, eds. (1994). Anne Thackeray Ritchie: Journals and letters. Columbus: Ohio State Univ. Press. ISBN 9780814206386.

- Williams, Ioan M. Thackeray. London: Evans, 1968.

External links

| Library resources about William Makepeace Thackeray |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Makepeace Thackeray. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Makepeace Thackeray |

- Works by William Makepeace Thackeray at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Makepeace Thackeray at Internet Archive

- Works by William Makepeace Thackeray at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Thackeray at eBooks @ Adelaide

- PSU's Electronic Classics Series William Makepeace Thackeray site

- On Charity and Humor, discourse on behalf of a charitable organisation

- Pegasus in Harness: Victorian Publishing and W. M. Thackeray by Peter L. Shillingsburg

- "Bluebeard's Ghost" by W. M. Thackeray (1843)

- "The Adventures of Thackeray on his way through the World: An online exhibition at the Houghton Library