Xu Xilin

| Xu Xilin | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 徐錫麟 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 徐锡麟 | ||||||

| |||||||

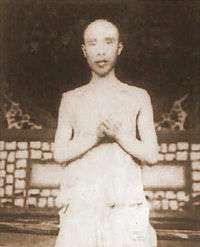

Xu Xilin (1873 – 7 July 1907), was a Chinese revolutionary born in Dongpu, Shanyin, Shaoxing, Zhejiang during the Qing dynasty.

Xu was sent to Japan in 1903 for study where he joined other Zhejiang students in rescuing Zhang Taiyan, who was arrested for spreading Anti Qing views. Xu set up a publishing house and a public school called Yuejun in Shaoxing with Zong Nengsu and Wang Ziyu.

Xu was recommended into the China restoration Society, Guangfuhui in 1904 by Cai Yuanpei and Tao Chengzhang in Shanghai. Xu entered the imperial exams and he met his cousin, Qiu Jin. He introduced her into the Guangfuhui.

Fan Ainong was a student of Xu.[1][2]

Xu refused to join Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary league, the Tongmenghui, when his Guangfuhui organization was merged into it.[3]

In 1906, Xu purchased an official rank and was placed in charge of police HQ of Anqing in Anhui province.[4]

On July 6, 1907, he was arrested before the scheduled Anqing Uprising, part of the Xinhai Revolution. During his interrogation, Xu said he had murdered En Ming, provincial governor of Anhui Province, just because En Ming was a Manchu, and he had a hit list of Manchu officials he was prepared to assassinate, admitting that he hated Manchus in general.[5] He was executed the next day by a firing squad, and his heart and liver were cut out by En Ming's bodyguards; a week later Qiu Jin was beheaded for her association with the plot.[6][7]

References

- ↑ Jon Eugene von Kowallis, Xun Lu (1996). The lyrical Lu Xun: a study of his classical-style verse. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-8248-1511-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Xun Lu, William A. Lyell (1990). Diary of a madman and other stories. University of Hawaii Press. p. xxxiii. ISBN 0-8248-1317-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Wu Yuzhang (2001). Recollections of the Revolution of 1911: A Great Democratic Revolution of China. The Minerva Group, Inc. p. 76. ISBN 0-89875-531-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Elisabeth Kaske (2008). The politics of language in Chinese education, 1895-1919. BRILL. p. 180. ISBN 90-04-16367-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Edward J. M. Rhoads (2001). Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928. University of Washington Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-295-98040-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Arif Dirlik (1993). The Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution. University of California Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-520-08264-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Jon Eugene von Kowallis, Xun Lu (1996). The lyrical Lu Xun: a study of his classical-style verse. University of Hawaii Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-8248-1511-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.