Shishupala Vadha

The Shishupala Vadha (Sanskrit: शिशुपालवध, IAST: Śiśupāla-vadha, lit. "the slaying of Shishupala") is a work of classical Sanskrit poetry (kāvya) composed by Māgha in the 7th or 8th century. It is an epic poem in 20 sargas (cantos) of about 1800 highly ornate stanzas,[1] and is considered one of the six Sanskrit mahakavyas, or "great epics". It is also known as the Māgha-kāvya after its author. Like other kavyas, it is admired more for its exquisite descriptions and lyrical quality than for any dramatic development of plot. Its 19th canto is noted for verbal gymnastics and wordplay; see the section on linguistic ingenuity below.

Contents

As with most Sanskrit kāvya, the plot is drawn from one of the epics, in this case the Mahabharata. In the original story, Shishupala, king of the Chedis in central India, after insulting Lord Krishna several times in an assembly, finally enrages him and has his head struck off. The 10th-century literary critic Kuntaka observes that Magha arranges the story such that the sole purpose of Vishnu's Avatarhood as Krishna is the slaying of the evil Shishupala. Magha also invents a conflict in Krishna's mind, between his duty to destroy Shishupala, and to attend Yudhishthira's ceremony to which he has been invited; this is resolved by attending the ceremony to which Shishupala also arrives and is killed.

The following description of the plot of the Shishupala Vadha is drawn from A. K. Warder.[2] The evil Shishupala has previously clashed with Krishna many times, such as when the latter eloped with Rukmini who was betrothed to him, and defeated the combined armies of Shishupala and Rukmini's brother Rukmi. When the story begins, Sage Narada reminds Krishna that while he had previously (in the form of Narasimha) killed Hiranyakashipu, the demon has been reborn as Shishupala and desires to conquer the world, and must be destroyed again.[2] Meanwhile, Yudhiṣṭhira and his brothers, having conquered the four directions and killed Jarasandha, wish to perform the Rajasuya yajña (ceremony) and Krishna has been invited. Unsure what to do (Canto II), Krishna takes the counsel of his brother Balarama and of Uddhava. While Balarama suggests attacking declaring war on Shishupala immediately, Uddhava points out that this would involve many kings and disrupt Yudhishthira's ceremony (where their presence is required). Instead, he suggests ensuring that Shishupala attends the ceremony as well. Pleased with this plan, Krishna sets out (Canto III) with his army to Indraprastha where the ceremony will be held. On the way, he sees Mount Raivataka (Canto IV), decides to camp there (Canto V), and all seasons simultaneously manifest themselves for his pleasure (Canto VI). His followers' enjoyment (Canto VII) and water sports (Canto VIII) are then described, as are nightfall (Canto IX), drinking and a general festival of love (Canto X) and dawn (Canto XI). These cantos, containing exquisite and detailed descriptions that are unrelated to the action, are usually the most popular with Sanskrit critics. The army resumes its march in Canto XII, and Krishna finally enters the city (Canto XIII). The ceremony takes place, and at the end, at Bhishma's advice, the highest honour (arghya) is bestowed on Krishna (Canto XIV). Shishupala is enraged at this (Canto XV), and makes a long speech on (what he considers) Krishna's bad qualities. He leaves the assembly. In Canto XVI, he sends a messenger to Krishna. Krishna declares war (Canto XVII), and the armies fight (Canto XVIII), with the various complex formations of the armies being matched by the complex forms Māgha adopts for his verses in Canto XIX. Finally, Krishna enters the fight (Canto XX), and after a long battle, strikes off Shishupala's head with Sudarshana Chakra, his discus.[2][3]

Despite what may appear to be little subject matter, the cantos of this work are in fact longer than those of other epics.[2]

Appraisal

The poet seems to have been inspired by the Kirātārjunīya of Bharavi, and intended to emulate and even surpass it. Like the Kirātārjunīya, the poem displays rhetorical and metrical skill more than the growth of the plot[4] and is noted for its intricate wordplay, textual complexity and verbal ingenuity. It has a rich vocabulary, so much so that the (untrue) claim has been made that it contains every word in the Sanskrit language.[5] The narrative also wanders from the main action solely to dwell on elegant descriptions, with almost half the cantos having little to do with the proper story[6] e.g. while describing the march of an army, cantos 9 to 11 take a detour to describe nature, sunrise and sunset, the seasons, courtesans preparing to receive men, the bathing of nymphs, and so on.[7] Because of these descriptions, the Śiśupālavadha is an important source on the history of Indian ornaments and costumes, including its different terms for dress as paridhāna, aṃśuka, vasana, vastra and ambara; upper garments as uttarīya; female lower garments as nīvī, vasana, aṃśuka, kauśeya, adhivāsa and nitambaravastra; and kabandha, a waist-band.[8] Magha is also noted for technique of developing the theme, "stirring intense and conflicting emotions relieved by lighter situations".[9] The work is primarily in the vīra (heroic) rasa (mood).[2]

In the 20th stanza of the fourth canto, Māgha describes the simultaneous setting of the sun and the rising of the moon on either side of the Meru mountain as like a mighty elephant with two bells dangling on either side of his body. This striking imagery has earned Māgha the sobriquet of Ghaṇṭāmāgha, "Bell-Māgha".[10] His similes are also highly original, and many verses from the work are of independent interest, and are quoted for their poetic or moral nature.[6][11][12][13][14]

Whereas Bhāravi glorifies Shiva, Māgha glorifies Krishna; while Bhāravi uses 19 metres Māgha uses 23, like Bhāravi's 15th canto full of contrived verses Māgha introduces even more complicated verses in his 19th.[6] A popular Sanskrit verse about Māgha (and hence about this poem, as it his only known work and the one his reputation rests on) says:

- उपमा कालिदासस्य भारवेरर्थगौरवम् ।

- दण्डिन: पदलालित्यं माघे सन्ति त्रयो गुणाः ॥

- upamā kālidāsasya, bhāraverarthagauravam,

- daṇḍinaḥ padalālityaṃ — māghe santi trayo guṇāḥ

- "The similes of Kalidasa, Bharavi's depth of meaning, Daṇḍin's wordplay — in Māgha all three qualities are found."

Thus, Māgha's attempt to surpass Bharavi appears to have been successful; even his name seems to be derived from this feat: another Sanskrit saying goes tāvat bhā bhāraveḥ bhāti yāvat māghasya nodayaḥ, which can mean "the lustre of the sun lasts until the advent of Maagha (the coldest month of winter)", but also "the lustre of Bharavi lasts until the advent of Māgha".[15] However, Māgha follows Bhāravi's structure too closely, and the long-windedness of his descriptions loses the gravity and "weight of meaning" found in Bhāravi's poem. Consequently, Māgha is more admired as a poet than the work is as a whole, and the sections of the work that may be considered digressions from the story have the nature of an anthology and are more popular.[2] His work is also considered to be difficult, and reading it and Meghadūta can easily consume one's lifetime, according to the saying (sometimes attributed to Mallinātha) māghe meghe gataṃ vayaḥ. ("In reading Māgha and Megha my life was spent", or also the unrelated meaning "In the month of Magha, a bird flew among the clouds".)

Linguistic ingenuity

Besides its poetry, the poem also revels in wordplay and ingeniously constructed verses. The second canto contains a famous verse with a string of adjectives that can be interpreted differently depending on whether they are referring to politics (rāja-nīti, king's policy) or grammar.[16] The entire 16th canto, a message from Shishupala to Krishna, is intentionally ambiguous and can be interpreted in two ways — a humble apology in courteous words, or a declaration of war.[2] The 19th canto, especially, like the 15th canto of Kirātārjunīya, contains chitrakavya or decorative composition, with many examples of constrained writing. Its third stanza, for instance, contains only the consonant 'j' in the first line, 't' in the second, 'bh' in the third, and 'r' in the fourth:[4]

Devanagari

जजौजोजाजिजिज्जाजी

तं ततोऽतितताततुत् ।

भाभोऽभीभाभिभूभाभू-

रारारिररिरीररः ॥IAST

jajaujojājijijjājī

taṃ tato'titatātatut

bhābho'bhībhābhibhūbhābhū-

rārārirarirīraraḥ"Then the warrior, winner of war, with his heroic valour, the subduer of the extremely arrogant beings, he who has the brilliance of stars, he who has the brilliance of the vanquisher of fearless elephants, the enemy seated on a chariot, began to fight."[6]

He progresses to just two consonants in the 66th stanza:[17]

भूरिभिर्भारिभिर्भीराभूभारैरभिरेभिरे ।

भेरीरेभिभिरभ्राभैरभीरुभिरिभैरिभाः ॥bhūribhirbhāribhirbhīrābhūbhārairabhirebhire

bherīrebhibhirabhrābhairabhīrubhiribhairibhāḥ"The fearless elephant, who was like a burden to the earth because of its weight, whose sound was like a kettle-drum, and who was like a dark cloud, attacked the enemy elephant."

By the 114th stanza, this is taken to an extreme, with a celebrated example involving just one consonant:[17]

दाददो दुद्ददुद्दादी दाददो दूददीददोः ।

दुद्दादं दददे दुद्दे दादाददददोऽददः ॥dādado duddaduddādī dādado dūdadīdadoḥ

duddādaṃ dadade dudde dādādadadado'dadaḥ"Sri Krishna, the giver of every boon, the scourge of the evil-minded, the purifier, the one whose arms can annihilate the wicked who cause suffering to others, shot his pain-causing arrow at the enemy."

The same canto also contains increasingly ingenious palindromes. The 44th stanza, for instance, has each line a palindrome:

वारणागगभीरा सा साराभीगगणारवा ।

कारितारिवधा सेना नासेधा वारितारिका ॥vāraṇāgagabhīrā sā sārābhīgagaṇāravā /

kāritārivadhā senā nāsedhā vāritārikā"It is very difficult to face this army which is endowed with elephants as big as mountains. This is a very great army and the shouting of frightened people is heard. It has slain its enemies."[17]

The 88th stanza is a palindrome as a whole (syllable-for-syllable), with the second half being the first half reversed. This is known as pratiloma (or gatapratyāgata) and is not found in Bharavi:[18]

तं श्रिया घनयानस्तरुचा सारतया तया ।

यातया तरसा चारुस्तनयानघया श्रितं ॥taṃ śriyā ghanayānastarucā sāratayā tayā

yātayā tarasā cārustanayānaghayā śritaṃ

The 34th stanza is the 33rd stanza written backwards, with a different meaning. Finally, the 27th stanza is an example of what has been called "the most complex and exquisite type of palindrome ever invented".[19] Sanskrit aestheticians call it sarvatobhadra, "perfect in every direction" — it yields the same text if read forwards, backwards, down, or up:

सकारनानारकास-

कायसाददसायका ।

रसाहवा वाहसार-

नादवाददवादना ॥

sakāranānārakāsa-

kāyasādadasāyakā

rasāhavā vāhasāra-

nādavādadavādanā.

sa kā ra nā nā ra kā sa kā ya sā da da sā ya kā ra sā ha vā vā ha sā ra nā da vā da da vā da nā (and the lines reversed) nā da vā da da vā da nā ra sā ha vā vā ha sā ra kā ya sā da da sā ya kā sa kā ra nā nā ra kā sa "[That army], which relished battle (rasāhavā) contained allies who brought low the bodes and gaits of their various striving enemies (sakāranānārakāsakāyasādadasāyakā), and in it the cries of the best of mounts contended with musical instruments (vāhasāranādavādadavādanā)."

The 29th stanza can be arranged into the shape of a "drum" (muraja-citra):[17][20]

सा सेना गमनारम्भे

रसेनासीदनारता ।

तारनादजनामत्त

धीरनागमनामया ॥

sā se nā ga ma nā ra mbhe ra se nā sī da nā ra tā tā ra nā da ja nā ma tta dhī ra nā ga ma nā ma yā The first, second, third, and fourth lines give the same text when read along a "drum" pattern.

"That army was very efficient and as it moved, the warrior heroes were very alert and did their duties with great concentration. The soldiers in the army made a loud sound. The army was adorned with intoxicated and restive elephants. No one was there with any thought of pain."

In the 118th stanza, each half contains the same pāda twice, but with different meanings. This is known as samudga:[18]

सदैव संपन्नवपू रणेषु

स दैवसंपन्नवपूरणेषु ।

महो दधे 'स्तारि महानितान्तं

महोदधेस्तारिमहा नितान्तम् ॥sadaiva saṃpannavapū raṇeṣu

sa daivasaṃpannavapūraṇeṣu

maho dadhe 'stāri mahānitāntaṃ

mahodadhestārimahā nitāntam

The canto also includes stanzas which can be arranged into the shape of a sword,[21] zigzags, and other shapes.

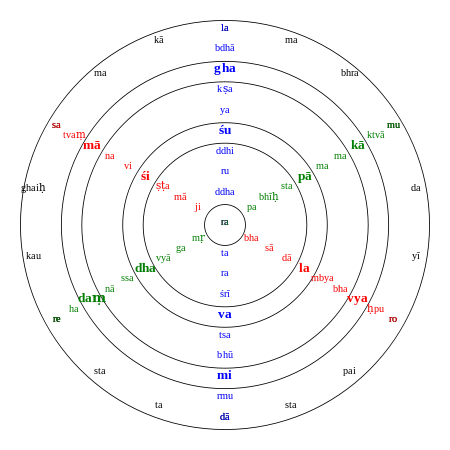

Finally, it ends with a stanza (120th) in the extremely difficult "wheel design" known as cakra-vṛtta or cakrabandha,[18] wherein the syllables can be arranged in the form of a wheel with six spokes.[22][23]

सत्वं मानविशिष्टमाजिरभसादालम्ब्य भव्यः पुरो

लब्धाघक्षयशुद्धिरुद्धरतरश्रीवत्सभूमिर्मुदा ।

मुक्त्वा काममपास्तभीः परमृगव्याधः स नादं हरे-

रेकौघैः समकालमभ्रमुदयी रोपैस्तदा तस्तरे ॥

satvaṃ mānaviśiṣṭamājirabhasādālambya bhavyaḥ puro

labdhāghakṣayaśuddhiruddharataraśrīvatsabhūmirmudā /

muktvā kāmamapāstabhīḥ paramṛgavyādhaḥ sa nādaṃ hare-

rekaughaiḥ samakālamabhramudayī ropaistadā tastare //

In the figure, the first, second and third lines are read top-to-bottom along the "spokes" of the wheel, sharing a common central syllable, while the fourth line is read clockwise around the circumference (starting and ending where the third line ends), sharing every third syllable with one of the first three lines. Further, the large syllables in bold (within the annuli), read clockwise, spell out śiśupālavadha-māgha-kāvyamidaṃ ("This is Śiśupālavadha, a poem by Māgha").

Derivatives

Māgha influenced Ratnākara's Haravijaya,[24] an epic in 50 cantos that suggests a thorough study of the Shishupalavadha.[6] The Dharmashramabhyudaya, a Sanskrit poem by Hari[s]chandra in 21 cantos on Dharmanatha the 15th tirthankara, is modeled on the Shishupalavadha.[25]

The oldest known commentary on the Śiśupālavadha is that by Vallabhadeva, known as the Sandehaviṣauṣadhi. The commentary by Mallinātha is known as the Sarvaṅkaṣā,[26] and, as on the other five mahakavyas, is considered the pre-eminent one. There are numerous other commentaries on it from different parts of the country, illustrating its importance.[27]

The Marathi writer Bhaskarabhatta Borikar, of the early 14th century, wrote a Shishupala Vadha in Marathi (1308).[7]:1186

References

- ↑ S. S. Shashi (1996), Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., p. 160, ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A. K. Warder (1994), Indian kāvya literature: The ways of originality (Bāna to Dāmodaragupta), 4 (reprint ed.), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., pp. 133–144, ISBN 978-81-208-0449-4

- ↑ Mrs. Manning (Charlotte Speir) (1869), Ancient and mediaeval India, Volume 2, Wm. H. Allen, pp. 134–136

- 1 2 Sisir Kumar Das; Sahitya Akademi (2006), A history of Indian literature, 500-1399: from courtly to the popular, Sahitya Akademi, p. 74, ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of literature, Merriam-Webster, 1995, p. 712, ISBN 978-0-87779-042-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moriz Winternitz; Subhadra Jha (transl.) (1985), History of Indian literature, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., pp. 72–77, ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4

- 1 2 Amaresh Datta, ed. (2006), The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume Two) (Devraj To Jyoti), Volume 2, Sahitya Akademi, p. 1204, ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0

- ↑ Sulochana Ayyar; Gwalior Museum (1987), Costumes and ornaments as depicted in the sculptures of Gwalior Museum, Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-002-4

- ↑ Jayant Gadkari (1996), Society and religion: from Rugveda to Puranas, Popular Prakashan, p. 205, ISBN 978-81-7154-743-2

- ↑ Mohan Lal, ed. (2006), Encyclopaedia of Indian literature, Volume 5, Sahitya Akademi, p. 4126, ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3

- ↑ John Telford; Benjamin Aquila Barber (1876), William Lonsdale Watkinson; William Theophilus Davison, eds., The London quarterly review, Volume 46, J.A. Sharp, p. 327

- ↑ Ramnarayan Vyas (1992), Nature of Indian culture, Concept Publishing Company, p. 56, ISBN 978-81-7022-388-7

- ↑ Manohar Laxman Varadpande (2006), Woman in Indian sculpture, Abhinav Publications, p. 90, ISBN 978-81-7017-474-5

- ↑ P. G. Lalye (2002), Mallinātha, Sahitya Akademi, p. 108, ISBN 978-81-260-1238-1

- ↑ D. D. (Dhruv Dev). Sharma (2005), Panorama of Indian anthroponomy, Mittal Publications, p. 117, ISBN 978-81-8324-078-9

- ↑ George Cardona (1998), Pāṇini: a survey of research, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 280, ISBN 978-81-208-1494-3

- 1 2 3 4 Sampadananda Mishra; Vijay Poddar (2002), The wonder that is Sanskrit, Sri Aurobindo Society, pp. 36–, ISBN 978-1-890206-50-5

- 1 2 3 C.R. Swaminathan; V. Raghavan (2000), Janakiharana of Kumaradasa, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 130, ISBN 978-81-208-0975-8

- ↑ George L. Hart, letter to Scientific American, November 1970. Reprinted in Martin Gardner, Mathematical Circus, p. 250, and in The colossal book of mathematics, W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, p. 30, ISBN 978-0-393-02023-6

- ↑ Ingalls, D. H. H. (1989). "Ānandavardhana's Devīśataka". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 109 (4): 565–575. doi:10.2307/604080. JSTOR 604080.

- ↑ Edwin Gerow (1971), A glossary of Indian figures of speech, Walter de Gruyter, p. 180, ISBN 978-3-11-015287-6

- ↑ Kalanath Jha (1975), Figurative Poetry in Sanskrit Literature, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 63, ISBN 978-81-208-2669-4

- ↑ Illustration

- ↑ Hermann Jacobi (1890), "Ānandavardhana and the date of Māgha", Vienna Oriental Journal, 4: 240

- ↑ Sujit Mukherjee (1999), A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings-1850, Orient Blackswan, p. 95, ISBN 978-81-250-1453-9

- ↑ R. Simon (1903), "Magha, Shishupalavadha II, 90", Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Volume 57, Kommissionsverlag F. Steiner, p. 520

- ↑ K B Pathak (1902), "On the date of the poet Mâgha", Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 20, p. 303

External links

- Transliterated text at GRETIL

- Description of Mount Raivataka from Shishupala vadha, translated by K. Krishnamoorthy

- The Shishupala story

- Translation of the Mahabharata, sections XXXV–XLIV of the second book provide the basis for the story

- Translation by Paul Wilmot, part of the Clay Sanskrit Library translation, ISBN 978-0-8147-9406-7.