2003 Canberra bushfires

| 2003 Canberra bushfires | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Canberra, Australian Capital Territory |

| Statistics | |

| Cost | $350 million |

| Date(s) | 8–21 January 2003 |

| Cause | Lightning strikes in Brindabella and Namadgi National Parks |

| Land use | Urban/rural fringe areas, farmland and forest reserves |

| Buildings destroyed | 488 |

| Injuries | 435 |

| Fatalities | 4 |

The 2003 Canberra bushfires involved several deaths, over 490 injured, and caused severe damage to the outskirts of Canberra, the capital city of Australia, during 18–22 January 2003. Almost 70% of the Australian Capital Territory's (ACT) pastures, forests (pine plantations), and nature parks were severely damaged, and most of the renowned Mount Stromlo Observatory was destroyed. After burning for a week around the edges of the ACT, the fires entered the suburbs of Canberra on 18 January 2003. Over the next ten hours, four people died and more than 500 homes were destroyed or severely damaged, requiring a significant relief and reconstruction effort.

Buildup to the event

On 8 January 2003, lightning strikes started four fires in NSW, over the border but in close proximity to Canberra. Despite their proximity and very small initial sizes, low intensity, and low rate of spread, these fires were not extinguished or contained by NSW emergency services personnel. Subsequent inquiries into the bushfires, including the Roche report, the McLeod inquiry, and the Coroners Report, identified poor management of the initial response as a key contributor to the disaster that unfolded on 18 January 2003.

On 13 January, a helicopter that had been waterbombing the fires in the forests west of Canberra crashed into Bendora Dam with one person, the pilot, injured. ACT Chief Minister Jon Stanhope and Chief Fire Officer Peter Lucas-Smith were reviewing the fires nearby in the Snowy Hydro SouthCare helicopter. The pilot of the Southcare chopper cautiously positioned his aircraft to allow Stanhope, Lucas-Smith and a paramedic on board to dive into the dam and rescue the injured pilot. All three who rescued the injured pilot and the helicopter pilot later received awards for their bravery.

On 17 January, the Emergency Services Bureau (ESB) released its final media release prior to 18 January at 8:50 pm.[1] This media release differed to any previous one in format and content. It also provided several clues that were overlooked in the assessment of the risk Canberra faced. For example, one point of the release stated that bushfire logistical support staging areas were being relocated from Bulls Head and Orroral Valley (far outside urban Canberra) to the North Curtin District Playing Fields (far inside urban Canberra),[2] signalling both a major retreat by fire fighters and pointing to imminent danger to the city itself.

Events of 18 January

The morning of Saturday 18 January 2003 was hot, windy and dry. Temperatures as high as 40 °C (104 °F) and winds exceeding 60 kilometres per hour (37 miles per hour), plus a very low relative humidity, were the main weather features of the day. Two fires continued to burn out of control in the Namadgi National Park, with the entire park, along with the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve, being closed due to the threat. A second fire, in the Brindabella Ranges, was threatening to break containment lines.

By 9 am on the morning of Saturday 18 January, burned leaves appeared on lawns in houses in the Weston Creek, Kambah, and Tuggeranong suburbs bordering the western extremity of Canberra. By 10 am, news helicopters were overflying Duffy and reporting news of the fires interstate and internationally, but no news was available locally.

Throughout the day, the fires burned closer to the fringes of Canberra's suburbs, and there was no sign of authorities gaining control of the situation. At around 2 pm, police evacuated the township of Tharwa to the south of Canberra.

By mid-afternoon, it had become apparent that the fires posed an immediate threat to the settlements near Canberra, such as Uriarra and Stromlo, as well as to the houses on the city's urban-bushland interface. A state of emergency was declared at 2.45 pm by the ACT's Chief Minister, Jon Stanhope.

The fires reached the urban area at 3 pm. The first emergency warning advisories were broadcast shortly after, on radio and television, with the advisories updated throughout the day. These advisories, accompanied by the Emergency Warning Signal stated that a significant "deterioration" of the fire situation in the ACT had occurred and placed several suburbs on alert to evacuate. As the day continued, these advisories advised the evacuation of several suburbs (also enforced by Police on the ground) and placed most suburbs of Canberra on some level of alert. By now, the fire had reached the fringes of many suburbs, was surrounding Tharwa, and threatened the historic Lanyon Homestead, which was hosting a wedding and protected by only a single fire truck.

By 3.50 pm, some houses were alight in the suburbs of Duffy and Chapman, with the loss of a home in Holder soon after. An ACT Fire Brigade unit, perceiving the fire from a vantage point in Fyshwick, overrode instructions by the radio controller to ignore the signs and remain where they were. The unit headed to Duffy, attempting to alert both controllers and residents to the imminent danger. That unit was caught in a fire front on Warragamba Avenue Duffy at around 4.10 pm, after having rescued at least two residents. Both the crew and residents were forced to flee the appliance when the fire struck.

Due to fire damage to infrastructure and extreme winds bringing down powerlines across the area, large parts of the city lost power. Fires also started in Giralang because of powerline problems. Evacuation centres were set up at four schools – Canberra College, Ginninderra College, Erindale College, and Narrabundah College. A dark cloud hung over the city, and, although it was not in danger, Parliament House was closed.

By 5 pm, houses were reported destroyed in Duffy, Chapman, Kambah, Holder, and Rivett, as well as in the small forestry settlement of Uriarra. It was later found that the first casualty of the fires, an elderly woman named Dorothy McGrath, had died at the nearby Stromlo Forestry Settlement.[3] Escape for residents was hampered by poor warning and by the settlement's location, surrounded by the pine forest. Fires in the Michelago area forced the closure of the Monaro Highway into Canberra. Fires spread through the Kambah Pool area and into the suburb of Kambah, causing damage to many homes and one of the ACT's primary Urban and Rural fire stations.

Fire spread through parkland, crossing the Tuggeranong Parkway and Sulwood Drive finally engulfing Mount Taylor. Within an hour, houses were also burning in Torrens, on the slopes of Mount Taylor, and in Weston. The fires by now had inflicted severe damage to the city's infrastructure. Power supplies were cut to several suburbs. These outages affected both the Emergency Services Bureau's own headquarters in Curtin and the Canberra Hospital (running on back-up generators), which was under intense pressure from people suffering burns and smoke inhalation. In Curtin, the ESA headquarters was in danger from the fires. With back-up power available only to the Communications Centre, many personnel were forced to work on tables outside as Army Reserve personnel hosed down the building.[4] It was later noted that the ESB could have moved its operations away from danger to other emergency service locations such as the AFP Winchester Centre or Tuggeranong Police Station.[4] Water, gas, sewerage, and communications were heavily affected. Water, gas, and landline communications was unavailable to several suburbs due to damage to supply lines and city reservoirs. Mobile telecommunications were severely affected due to increased traffic, causing serious disruption to mobile phone networks and the ESA's own radio and dispatch networks. A local generator services business later reported on their website that the ash and smoke were so intense, that some back-up power diesel generators at communication and data centres failed to produce enough power due to air intake filters clogging up. At least one generator air intake filter burned as it sucked in burning leaves blowing in the strong winds.

The fires impacted part of the Lower Molonglo Water Quality Control Centre (LMWQCC), responsible for treating the city's sewage and waste water before its release into the Molonglo River. The plant's operations were disrupted due to fire damage, causing concern about the possible release of sewage into the Molonglo River, as the plant's reserve storage could only hold one day of surplus. However, the lack of resources and equipment failures for crews protecting the plant could have led to a catastrophe, as detailed in Danny Camilleri's testimony in Coroner Maria Doogan's subsequent inquest into the fires. Camilleri testified that his crews arrived to find much of the area around the plant on fire, with a significant risk of the fire endangering dangerous substances stored at the plant to treat waste, including chlorine.[5] He stated that if the fire had caused a breach in the chlorine tanks, it would have created "a poisonous cloud that would blow toward Canberra necessitating mass evacuations".[5]

By 10 pm, one of the four evacuation centres in Canberra was completely full, and the others were filling up quickly. Reports of looting also began to arrive from the damaged areas. Both Prime Minister John Howard and Governor General Peter Hollingworth changed their plans to return to Canberra as soon as was possible. While the very worst of the fires had passed, the situation was still far from stable, and going into Sunday, 19 January, houses were still ablaze across numerous suburbs.

Aftermath

By the evening of 19 January, it was clear that the worst-hit suburb was Duffy, where 200+ residences were destroyed,[6] and that four people had died: Alison Tener, 38, Peter Brooke, 74, and Douglas Fraser, 60, and Dorothy McGrath, 76, of the Mount Stromlo Forestry Settlement.[7][8] The loss of life, damage to property, and destruction of forests to the west of the city caused not just economic loss but significant social impacts.

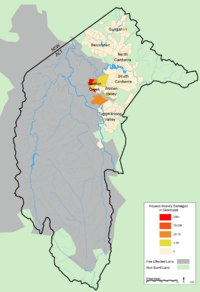

In the weeks after 18 January, the impact of the fires was studied in detail to determine how the damage had been done, and how to better work against such natural disasters in future. The Cities Project compiled information on as many as 431 damaged properties, stratified into the groups of "destroyed", "heavy damage", "medium damage", "light damage", and "superficial damage". This data was split by suburb to form a table which illustrated which areas had taken the most damage. The data allowed them to conclude that the high levels of "destroyed" property (91%) indicated the high speed with which the fire had moved. It was also concluded that once the establishments had caught fire, there was little chance of their being put out. In addition, the study showed that it was not only the fire which caused damage, but also the fierce winds recorded on the day, which were strong enough to uproot some small trees. It is believed that with the aid of this information, better policies and regulations have been formulated, which may help to reduce the destruction by future bushfires in Canberra, as well as in other locales.

Bushfires severely harmed the vegetation of the Cotter River Catchment and caused water quality problems in the three dams in the catchment: Corin, Bendora and Cotter Dams. For quite some time after the fires, turbidity in the water due to silt and ash from surrounding burnt-out forests meant Canberra had to rely on Googong Dam on the Queanbeyan River, which was not affected by the fires. Given the drought and existing water shortages, this effectively reduced Canberra's water reserves to around 15% for some time. An upgrade to the Stromlo Water Treatment Plant was subsequently required to allow extra filtration of water to cope with the diminished quality in the future.

As with any bushfire, the environment will take significant time to regenerate. Regeneration of vegetation was delayed by an ongoing drought in the region.

Mount Stromlo

Perhaps the most notable cultural and scientific loss caused by the fires was the damage to the scenic and renowned Mount Stromlo Observatory (headquarters of the Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics of the Australian National University), which is estimated to be the source of a third of Australia's astronomical research.[9] Five historically significant telescopes were destroyed. Instrumentation and engineering workshops, the observatory's library, and the main administration buildings were consumed. The visitors' centre or "Exploratory" housing public exhibits and cafe escaped the fires unscathed, despite being on the edge of a steep gradient, which fires had roared up, and being only metres from the 74-inch (1.88 m) telescope, which was completely destroyed.

The insurance payment sought by the Australian National University (ANU), amounting to 75 million Australian dollars, could have become the largest insurance claim in Australian history. However, in August 2009, during trial in the ACT Supreme Court, the 3 insurance companies settled out of court, paying the ANU an undisclosed sum.[10] A related claim against ANU's insurance broker, Aon Risk Services Australia Ltd, for failing to renew insurance coverage on some structures, was also settled for an unstated amount in June 2011.[11]

Canberra artist Tim Wetherell was commissioned by ANU[12] to produce a sculpture from the ruins of the Mount Stromlo telescopes. The finished sculpture was named "The Astronomer" and installed in the Parliamentary Triangle, outside Questacon.

Official responses

Following the 2003 bushfires, the ACT and New South Wales and Australian governments initiated community and official responses to the fire.

Bushfire Recovery Taskforce

The Bushfire Recovery Taskforce was established to advise the ACT Government, provide leadership for the recovery, and act as a bridge between Government agencies and the community.

McLeod Inquiry

The ACT Government established the McLeod Inquiry to examine and report on the operational response to the bushfires. The Inquiry was headed by Ron McLeod, a former Commonwealth Ombudsman. The Inquiry handed down its findings on 1 August 2003.

The inquiry found that:

- The fires, started by lightning strikes, might have been contained, had they been attacked more aggressively in the 24 hours after they broke out. Large stretches of dry, drought-affected vegetation and weather conditions that were extremely conducive to fire meant that once the fires reached a certain size, they were very difficult to control.

- Management of fuel load in parks and adequate access to remote areas were both lacking.

- Emergency service personnel performed creditably, but they were overwhelmed by the intensity of the fires and the unexpected speed of their advance on 18 January.

- A comprehensive ACT Emergency Plan was in place at the time of the fire; it worked, particularly in recovery after the fires, in dealing with the large number of people who needed temporary shelter and assistance as a consequence of the fires.

- Inadequacies in the physical construction and layout of the Emergency Services Bureau centre in Curtin were a hindrance. The centre was unable to handle efficiently the large amount of data and communications traffic into and out of the centre at the height of the crisis.

- There were some equipment and resourcing deficiencies within the ACT's emergency service organisations.

- Information and advice given to the community about the progress of the fires, the seriousness of the threat, and the preparations the public should be making was seriously inadequate. There was also confusion as to whether homes had to be evacuated.

The Inquiry recommended there should be increased emphasis given to controlled burning as a fuel-reduction strategy, access to and training of emergency personnel in remote areas needed to be improved and a number of changes be made to the emergency services and the policies that govern their operations, including a greater emphasis on provision of information to the public.

ACT Coroner's Bushfire Inquiry

The Coroner's inquiry commenced in January 2003, and hearing officially opened on 16 June 2003. The Coroner's Court of the Australian Capital Territory conducted an inquiry into the cause, origin, and circumstances of the 2003 bushfires and inquests into the four deaths associated with those fires. The inquiry was under the provisions of the ACT Coroners Act 1997.

The inquiry was marked by controversy, and in February 2005 the ACT Supreme Court heard an application that the coroner be disqualified due to bias. The inquiry into the fires was on hold until August 2005, when the Full Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its decision,[13] declaring that Coroner Maria Doogan should not be disqualified on the ground of a reasonable apprehension of bias. The inquiry reconvened on 17 August 2005.

After over 90 days of examining the evidence, the inquiry wrapped up on 25 October 2005. Although the inquiry was supposed to be completed in early 2006, submissions continued into mid-2006, with the Coroner delivering her findings, "The Canberra Firestorm",[14] in December 2006.

House Select Committee on the recent Australian bushfires

On 26 March 2003 the House of Representatives established a Select Committee to inquire into the recent Australian bushfires, including the Canberra bushfire. The committee tabled the report of its inquiry on 5 November 2003 and the Australian government presented its response to the report on 15 September 2005.

Canberra Fire Tornado

At one time during the bushfires in Canberra, a fire whirl or "fire tornado" was documented (and later confirmed). It was known to have winds exceeding 160 mph. Amazingly, the fire whirl was spawned by its own wind rotation from a pyrocumulonimbus cloud. It is the only fire tornado known to have ever exceeded F3 wind speeds on the Fujita scale.

Bushfire memorial

On 18 January 2006, three years after the day of the bushfires, a bushfire memorial was opened on land which had been affected by the fires in Stromlo forest.[15]

The ACT Bushfire Memorial was commissioned by the ACT government to acknowledge the impact of the fires and thank the many organisations and individuals who played crucial roles in the fire fighting and recovery efforts.

The memorial was designed by Canberra artists Tess Horwitz, Tony Steel and Martyn Jolly and incorporates elements requested by the ACT community. It is a journey from the day of the fire, through the process of recovery, to the honouring of memory.

The entrance memorial walls are made from the community's salvaged bricks, which are inscribed with messages of grief and gratitude. Beyond the walls, a site framed by a grove of casuarinas contains red glass and metal forms, referring to the force of the firestorm and to the lightning strikes that sparked the main fires. An avenue leads to an amphitheatre enclosing a pond and bubbling spring. Glass columns bordering the pond contain details from photos provided by the community which speak of memory and human resilience.

On 18 February 2006, an independent group of fire victims installed a plaque to honour the four people who died in the fires and the volunteer firefighters who fought so hard. The plaque is located at the end of the walkway to the memorial, immediately before the memorial walls. Fire victims and residents held a simple ceremony to mark the occasion.

As of early March 2006, the memorial is not quite finished. Apart from the immature casuarina trees, which will take time to grow to full height, there remains landscaping and plumbing work yet to be completed. The area where the memorial is located is undergoing significant redevelopment for recreational purposes, and will not be replanted with pine forest. Strategies that have been put in place so this disaster will not occur again include land management practices, the urban perimeter, the role of Government and community responsibility in bushfire management, urban design, and vegetation and housing design.

Notes

- ↑ "5", The Canberra Firestorm: Inquests and inquiry into four deaths and four fires between 8 and 18 January 2003 (PDF), The Canberra Firestorm, 1, p. 306, paragraph 5, retrieved 20 April 2015

- ↑ "5", The Canberra Firestore, 1, p. 307

- ↑ "8", The Canberra Firestorm (PDF), 4, pp. 183–187, retrieved 20 April 2015

- 1 2 Ullman, Chris. "Stateline". ABC Canberra.

- 1 2 "5", The Canberra Firestorm (PDF), The Canberra Firestorm, 1, p. 358, paragraph 4, retrieved 20 April 2015

- ↑ "Canberra Bushfires Fieldwork" (PDF). Geoscience Australia. Australian Government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ↑ "8", The Canberra Firestorm, 4, pp. 183, 188, 192 & 194, retrieved 20 April 2015

- ↑ "Blame laid for firestorm deaths". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 19 December 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ↑ "Firestorms destroy Australian observatory". New Scientist. 20 January 2003. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- ↑ "The High Court warns against last-ditch amendments in litigation". Corrs, Garth, Chambers - Lawyers. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ "Bushfire damages win for ANU". ABC Canberra. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ "The Stromlo Orrery Project". Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ http://www.courts.act.gov.au/supreme/judgment/view/2868/title/r-v-doogan

- ↑ http://www.courts.act.gov.au/magistrates/publication/view/1074 "The Canberra Firestorm"

- ↑ "Hundreds gather for bushfire memorial". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2003 Canberra bushfires. |

- Mount Stromlo Fire of 18 January 2003 – official RSAA ANU photos, articles, accounts and reconstruction details

- Media footage and images of the 2003 Canberra firestorm

- Bushfires, Canberra, A.C.T., January 2003 – Australian Internet Sites – websites in the PANDORA archive

- ACT CORONER’S BUSHFIRE INQUIRY web page

- "Canberra Bushfires". Geoscience Australia. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14.

- Sydney Morning Herald report on the findings of the New South Wales Deputy Coroner

- Article in The Age February 2005 concerning the delay in the coronial inquiry

- Bushfire coronial website – Dedicated to bringing evidence directly from witnesses to the public.

- Opinion piece by Jack Waterford, editor of The Canberra Times on the outcomes of the coronial inquiry

- Dealing with Disaster – Using new Networking Technology for Emergency Coordination Some of the Satellite Technology Used for Mapping the Fires Image galleries

- Fighting bushfires on the Mount Franklin Road, Brindabella Ranges, on the night of 11/12 January 2003 / David Tunbridge

- Canberra fire damage, 18 January to 14 February 2003 / Damian McDonald, Greg Power and Loui Seselja.

- Canberra bushfires, 18 January to 14 February 2003 / Tony Miller

- Canberra bushfires, 2003 / Christine Thomas and Simon Mockler

- Canberra Bushfires 2003 / Peter Dey

- ABC News report on 18 February 2006 memorial gathering

- Canberra Fire Museum "EXTREME: Canberra Fires 2003"

- Canberrafires gallery and stories

- ↑ "ACT Government Agency submissions to the Inquiry into the Operational Response to the January 2003 Bushfires". pandora.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ Flight Safety Magazine article March/April 2003 on aerial bush fire fighters cached by WayBack Machine