2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill

|

| |

| Date | August 5, 2015 |

|---|---|

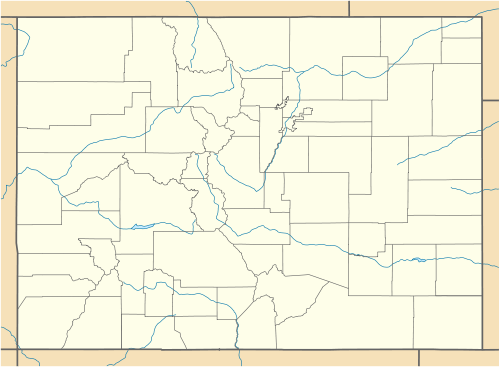

| Location |

Gold King Mine Silverton, Colorado, United States |

| Coordinates | 37°53′40″N 107°38′18″W / 37.89444°N 107.63833°WCoordinates: 37°53′40″N 107°38′18″W / 37.89444°N 107.63833°W |

| Cause | Accidental wastewater release, approx. 3 million US gal (11 ML) |

| Participants | Environmental Protection Agency |

| Outcome |

River closures (until about Aug 17 with ongoing tests) Ongoing water supply & irrigation issues |

| Waterways affected | Animas and San Juan rivers |

| States affected | Colorado, New Mexico, Utah |

| Website | EPA updates |

The 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill is a 2015 environmental disaster at the Gold King Mine near Silverton, Colorado.[2] On August 5, 2015, EPA personnel, along with workers for Environmental Restoration LLC (a Fenton, Missouri, company under EPA contract to mitigate pollutants from the closed mine), caused the release of toxic wastewater when attempting to add a tap to the tailing pond for the mine.[3] The maintenance by EPA was necessary because local jurisdictions had previously refused Superfund money to fully remediate the regions' derelict mines, due to a fear of lost tourism.[4] After the spill, the Silverton Board of Trustees and the San Juan County Commission approved a joint resolution seeking Superfund money.[5]

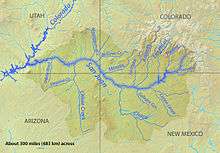

Workers accidentally destroyed the plug holding water trapped inside the mine, which caused an overflow of the pond, spilling three million US gallons (11 ML) of mine waste water and tailings, including heavy metals such as cadmium and lead, and other toxic elements, such as arsenic,[6] beryllium,[6] zinc,[6] iron[6] and copper[6] into Cement Creek, a tributary of the Animas River in Colorado.[7] The EPA was criticized for not warning Colorado and New Mexico about the operation until the day after the waste water spilled, despite the fact the EPA employee "in charge of Gold King Mine knew of blowout risk."[8]

The EPA has taken responsibility for the incident. Governor of Colorado John Hickenlooper declared the affected area a disaster zone. The spill affects waterways of municipalities in the states of Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, as well as the Navajo Nation. As of August 11, acidic water continued to spill at a rate of 500–700 US gal/min (1.9–2.6 m3/min) while remediation efforts were underway.[9]

Background

Gold mining in the hills around Gold King was the primary income and economy for the region until 1991, when the last mine closed near Silverton.[10] The Gold King Mine was abandoned in 1923.[11] Prior to the spill, the Upper Animas water basin had already become devoid of fish, because of the adverse environmental impacts of regional mines such as Gold King, which contaminants entered the water system.[10] Other plant and animal species were also adversely affected in the watershed before the Gold King Mine breach.[10]

Many abandoned mines throughout Colorado are known to have problems with acid mine drainage.[12] The chemical processes involved in acid mine drainage are common around the world: where subsurface mining exposes metal sulfide minerals such as pyrite to water and air, this water must be carefully managed to prevent harm to riparian ecology. At the time of the accident, the EPA was working at the Gold King Mine to stem the leaking mine water going into Cement Creek. Water was accumulating behind a plug at the mine's entrance. They planned to add pipes that would allow the slow release and treatment of that water before it backed up enough to blow out. Unknown to the crew, the mine tunnel behind the plug was already full of pressurized water. It burst through the plug soon after excavation began.

In the 1990s, sections of the Animas had been nominated by the EPA as a Superfund site for clean-up of pollutants from the Gold King Mine and other mining operations along the river. Lack of community support prevented its listing. Under the law, the EPA had authority to do only minor work to abate environmental impacts of the mine.[13] Locals had feared that classifying this as a Superfund site would reduce tourism in the area, which was the largest remaining source of income for the region since the closure of the metal mines.[10][14]

Prior reclamation

The Gold King's adits were dry for most of the mine's recent history, as the area was being drained from below by the Sunnyside Mine's American Tunnel. Sunnyside Mine closed in 1991. As part of a reclamation plan, the American Tunnel was sealed up in 1996. In the absence of drainage, by 2002 a new discharge of particularly contaminated water had begun to flow from the Gold King Level 7 adit. Flow there increased again after the nearby Mogul Mine was sealed by its owners in 2003.

In 2006, a spot measurement of flow from this adit showed a peak of 314 gallons per minute. The significance of this figure is unclear since flow was not being logged continuously.[15]:17-22 By this time, the Gold King was considered one of the worst acid mine drainage sites in Colorado. In 2009, the Colorado Department of Natural Resources Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety (DRMS) plugged all four Gold King Mine portals by stuffing them with old mine backfill; drainage pipes were installed to prevent water from ponding behind the entrance. This work was complicated by partial collapse of the mine tunnel near the entrance. It was noted that the drainage system might not be sufficient to prevent a future blowout.[15]:35

In 2014, Colorado DRMS asked the EPA to reopen and stabilize the Gold King 7 adit.[15]:35 Reportedly no maintenance on the existing drainage system had been performed since it was installed in 2009. It was noted that flow from the drains had decreased from 112 gpm to 12.6 gpm between August 25, 2014, and September 11, 2014. The cause of this decrease was unknown but attributed to seasonal variation.[15]:35 While excavating the opening, workers saw seepage at six feet above the bottom of the tunnel; they believed that meant that there was six feet of water backed up in the tunnel. Excavation at the entrance was postponed until 2015, so that a pond large enough to treat that volume of water could be constructed.[15]:36

The blowout

The EPA team returned in July 2015 to continue the work. They found that a landslide had covered the drainage pipes.[15]:42 When the slide was cleared, seepage was again observed at a level about 6 feet above the bottom of the mine entrance, which they thought was the level of pooled water behind the plug.[15]:46 They planned to excavate the entrance beginning from the level of the top of the mine tunnel down to what they took to be the top of the water, insert a pipe through that clearance, and drain the pooled water.[15]:47-52 DRMS and the EPA discussed the plan and came to an agreement. But they had misjudged the level of the water in the tunnel.

At around 10:51 AM on August 5, the backhoe operator saw a spurt of clear water spray about 2 ft out of a fracture in the wall of the plug, indicating that the mine tunnel was full of pressurized water.[note 1] Failure of the plug produced uncontrolled release within minutes.[15]:52-59 Rushing to Cement Creek, the torrent of water washed out the access road to the site.[15]:60

The EPA had considered drilling into the mine from above in order to measure the water level directly before beginning excavation at the entrance, as was done at nearby mines in 2011. Had they done so, they would have discovered the true water level, and changed their plan; the disaster would not have occurred.[15]:2 Operating mines have been required to perform such measurement of water level since a fatal mine flood in 1911.[15]:A-4

EPA risk awareness

Through a FOIA request, Associated Press obtained EPA files indicating that U.S. government officials "knew of ‘blowout’ risk for tainted water at mine," which could result from the EPA's intervention.[16] EPA authorities had learned of this risk through a June 2014 work order that read "Conditions may exist that could result in a blowout of the blockages and cause a release of large volumes of contaminated mine waters and sediment from inside the mine, which contain concentrated heavy metals." In addition, a May 2015 action plan for the mine "also noted the potential for a blowout."[16] An EPA spokeswoman was not able to state what precautions the EPA took.[16]

On February 11, 2016, the Denver Post reported that Hays Griswold, the EPA employee in charge of the Gold King mine, wrote in an e-mail to other EPA officials "that he personally knew the blockage "could be holding back a lot of water and I believe the others in the group knew as well.""[17] The Post added: "Griswold's e-mail appears directly to contradict those findings and statements he made to The Denver Post in the days after the disaster, when he claimed "nobody expected (the acid water backed up in the mine) to be that high." "[18]

Environmental impact

The Animas River was closed to recreation until August 14.[19] During the closure, county officials warned river visitors to stay out of the water.[20] Residents with wells in floodplains were told to have their water tested before drinking it or bathing in it. People were told to avoid contact with the river, including by their pets, and to prevent farmed animals from drinking the water. They were advised not to catch fish in the river. The Navajo Nation Commission on Emergency Management issued a state of emergency declaration in response to the spill; it has suffered devastating effects.[21][note 2]

People living along the Animas and San Juan rivers were advised to have their water tested before using it for cooking, drinking, or bathing. The spill was expected to cause major problems for farmers and ranchers who rely on the rivers for their livelihoods.[25]

The long-term impacts of the spill are unknown, as sedimentation is expected to dilute the pollutants as the spill cloud moves downstream.[26] The acid mine drainage temporarily changed the color of the river to orange.[27]

By August 7, the waste reached Aztec, New Mexico; the next day, it reached the city of Farmington, the largest municipality affected by the disaster. By August 10, the waste had reached the San Juan River in New Mexico and Shiprock (part of the Navajo Nation), with no evidence to that date of human injury or wildlife die-off. The heavy metals appeared to be settling to the bottom of the river. They are largely insoluble unless the entire river becomes very acidic.[13] The waste was initially expected to reach Lake Powell by August 12;[7] it arrived on August 14. It was expected to pass through the lake within two weeks.

The Utah Division of Water Quality said the remaining contaminants will be diluted to a point where there will be no danger to users beyond that point.[28] By August 11, pollutant levels at Durango returned to pre-incident levels.[9] On August 12, the leading edge of the plume was no longer visible due to dilution and sediment levels in the river.[29] The discharge rate of waste water at Gold King Mine was 610 gallons per minute as of August 12.[30]

Heavy metals

The EPA reported, August 10, 2015, that levels of six metals were above limits allowed for domestic water by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. The department requires municipalities to cease to use water when the levels in it exceed the limits. Some metals were found at hundreds of times their limits, e.g. lead 100 times the limit, iron 326 times the limit. Arsenic and cadmium were also above the limits. The measurement was made 15 miles (24 km) upstream from Durango.[6]

Government response

The EPA has taken responsibility for the incident.[7] Although the river turned a bright orange-yellow soon after the release, the EPA failed to notify local residents of the spill for more than 24 hours. Press and local officials sharply criticized the EPA for this slow response.[10] The Associated Press reported, 17 days after the spill: "In the wake of the spill, it has typically taken days to get any detailed response from the agency, if at all."[31]

On August 8, Governor of Colorado John Hickenlooper declared a disaster,[6] as did the leader of the Navajo Nation.[32]

On August 11, New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez declared a state of emergency in her state after viewing the affected river from a helicopter, and said her administration was ready to seek legal action against the EPA.[33]

Multiple municipalities and jurisdictions along the course of the river, including the Navajo Nation, stopped drawing drinking water from the Animas River because of heavy metal contamination.[26] The Navajo Nation President, Russell Begaye, advised his people with livestock and farming against signing a form from the EPA saying that the Environmental Protection Agency is not responsible for the damage to crops and livestock.[34] Despite assurances of safety from both the U.S. EPA and the Navajo Nation EPA, farmers of the Navajo Nation on August 22 voted unanimously to refrain from using water from the Animas River for one year, overruling president Russell Begaye. He had planned to announce the reopening of irrigation canals.[35]

Following the spill, the local governments of Silverton and San Juan County decided to accept Superfund money to fully remediate the mine.[5] The Federal Emergency Management Association (FEMA) rejected a request by the Navajo Nation to appoint a disaster-recovery coordinator.[32]

Impact on the Navajo Nation

The effects of the Gold King Mine spill on the Navajo Nation has included damage to their crops, home gardens, and cattle herds. The Navajo Nation ceased irrigating their crops from the San Juan River on August 7, 2015. While San Juan County in New Mexico lifted the ban on water from the San Juan River on August 15, 2015, the President of the Navajo Nation, Russell Begaye, who had ongoing concerns about the water’s safety, did not lift the Navajo Nation’s ban until August 21, 2015. This followed the Navajo Nation’s EPA completing its testing of the water.[36] During this time, the US EPA had water delivered to the Navajo Nation.

An estimated 2,000 Navajo farmers and ranchers were affected directly by the closing of the canals after the spill. While water was trucked into the area to provide water to fields, many home gardens and some remote farms did not receive any assistance.[37] They suffered widespread crop damage.

The EPA and the Navajo Nation are still disputing how to fairly compensate the Navajo for the damage caused by the spill. As of April 22, 2016, the Navajo Nation has been compensated a total of $150,000 by the EPA, according to testimony at hearings of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. According to President Begaye, this is only 8% of the costs incurred by the Navajo Nation. According to Senator John McCain, the Navajo Nation could incur up to $335 million in costs related to the spill.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The water was under pressure because the flooded adit sloped upward away from the entrance, gaining about 10 ft in elevation over 1,000 ft. If the water was 1 ft deep there, this would correspond to the weight of 11 feet of water on the plug.[15]:67

- ↑ The impact on the Navajo Nation has been reported in various publications: The Portland Press Herald reported that the disaster is "devastating to the Navajo Nation."[22] By August 12, the New York Post reported that "Bottled water on the Navajo Nation is becoming scarce.[23]". CNN reported: "the Navajo Nation in New Mexico appears to have the most at risk."[24]

References

- ↑ "How are they going to clean up that Colorado mine spill?", The Christian Science Monitor, August 13, 2015

- ↑ Schlanger, Zoë (August 7, 2015). "EPA Causes Massive Spill of Mining Waste Water in Colorado, Turns Animas River Bright Orange". Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ↑ Harder, Amy; Berzon, Alexandra; Forsyth, Jennifer (August 12, 2015). "EPA Contractor Involved in Colorado Spill Identified as Environmental Restoration". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ San Juan County votes yes for Superfund cleanup of old mines", Denver Post, 22 February 2016

- 1 2 "Silverton to seek federal cleanup help after Gold King Mine disaster". ABC 7 Denver. Aug 25, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Finley, Bruce; McGhee, Tom (August 10, 2015). "Animas mine disaster: Arsenic, cadmium, lead broke water limits". The Denver Post. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Kolb, Joseph J. (August 10, 2015). "'They're not going to get away with this': Anger mounts at EPA over mining spill". Fox News. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ↑ Jesse Paul (February 11, 2016). "EPA employee in charge of Gold King Mine knew of blowout risk, e-mail shows". The Denver Post.

- 1 2 "E.P.A. Treating Toxic Water From Abandoned Colorado Mine After Accident", NY Times, August 11, 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kaplan, Sarah (August 10, 2015). "What the EPA was doing when it sent yellow sludge spilling into a Colorado creek". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- ↑ Driessen, Paul (August 21, 2015). "EPA's gross negligence at Gold King". New Mexico Politics. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Bibliography, Watershed Contamination from Hard-Rock Mining — Hardrock Mining in Rocky Mountain Terrain — Upper Arkansas River, Colorado " U.S. Geological Survey, Toxic Substances Hydrology Program; accessed 2015-08-12.

- 1 2 "Residents demand health answers as mine spill fouls rivers". Yahoo News.

- ↑ "Colorado now faults EPA for mine spill after decades of pushing away federal Superfund help", Star Tribune, 11 August 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Technical Evaluation of the Gold King Mine Incident" (PDF). Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center. Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "EPA Knew of 'Blowout' Risk at Colorado Gold Mine on Animas River: Report". NBC News. The Associated Press. 22 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Jesse Paul (February 11, 2016). "EPA employee in charge of Gold King Mine knew of blowout risk, e-mail shows". The Denver Post.

- ↑ Jesse Paul The Denver Post (August 26, 2015). "EPA: Waste pressure evidently never checked before Colorado mine spill". denverpost.com.

- ↑ Michael Martinez, CNN (August 14, 2015). "Animas River reopens for recreation". CNN.

- ↑ "Environmental Agency Uncorks Its Own Toxic Water Spill at Colorado Mine", NY Times, 10 August 2015

- ↑ "EPA: Pollution from mine spill much worse than feared", USA Today, August 10, 2015

- ↑ "Southwest states may face long-term risk from Colorado mine spillage", Press Herald, August 12, 2015

- ↑ "Navajo Nation feels brunt of Colorado mine leak", NY Post, 12 August 2015

- ↑ "Damage to Navajo Nation water goes beyond money", CNN, 13 August 2015

- ↑ "'They're not going to get away with this': Anger mounts at EPA over mining spill", Fox News, August 10, 2015

- 1 2 "Gold mine's toxic plume extends to Utah". USA TODAY.

- ↑ Castillo, Mariano (August 10, 2015). "Pollution flowing faster than facts in EPA spill". CNN. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ↑ "River in Colorado Reopens as Toxic Plume Reaches Lake Powell". Associated Press. August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Gold King Mine spill update". Lake Powell Chronicle. August 12, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ Castillo, Mariano (August 14, 2015). "Gold King Mine owner: 'I foresaw disaster' before spill". CNN. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ "EPA knew of blowout risk ahead of Colorado mine accident". PBS NewsHour.

- 1 2 "Navajo Nation seeks assistance after Gold King Mine spill". Santa Fe New Mexican. October 3, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2015 – via Associated Press.

- ↑ "Contamination in Animas River becomes 'Declaration of Emergency'". KRQE News 13. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Tribe warns residents not to use EPA forms after spill", USA Today (online edition), 13 August 2015, retrieved 15 August 2015

- ↑ Laylin, Tafline (August 26, 2015). "Gold King mine spill: Navajo Nation farmers prohibit Animas river access". The Guardian. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Water flowing in Fruitland - Navajo Times". Navajo Times. 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ "Navajo Crops Drying Out as San Juan River Remains Closed After Toxic Spill". indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

External links

- EPA Region 8 Official Website for Event

- USGS Water Quality Data and Activities related to event

- Animas RIver spill six months later, an investigative report

- Cement Creek (USGS National Water Information System)

- Animas River below Silverton (USGS National Water Information System)

- Animas River at Durango (USGS National Water Information System)