41st Infantry Division (United States)

| 41st Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

|

41st Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia | |

| Active | 1917–68 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Role | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Nickname(s) | "Jungleers" or "Sunsetters" |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Major General George A. White Major General Horace H. Fuller Major General Jens A. Doe |

The 41st Infantry Division was composed of National Guard units from Idaho, Montana, Oregon, North Dakota and Washington that saw active service in World War I and World War II. It was one of the first to engage in offensive ground combat operations during the last months of 1942. In 1965 it was reorganized as the 41st Infantry Brigade. The brigade has seen combat in the Iraq War in 2003.

World War I

The 41st was first activated for U.S. Army service on 1 April 1917, just five days before the American entry into World War I, primarily from Guard units of the northwestern United States and trained at Camp Green, North Carolina. It consisted of the 81st Infantry Brigade (161st and 162nd Infantry Regiments) and the 82nd Infantry Brigade (163rd and 164th Infantry Regiments).[1] On 26 November 1917 the 41st Division embarked for Europe as part of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), commanded by General John J. Pershing. Men of the 41st were aboard the SS Tuscania when it was torpedoed by a German U-boat and sunk off the coast of Northern Ireland.

In France, however, the 41st Division received a major disappointment. It was designated a replacement division and did not go to combat as a unit. The majority of its infantry personnel went to the 1st, 2nd, 32nd and 42nd Infantry Divisions where they served throughout the war. The 147th Artillery Regiment was attached to the 32nd Division and saw action at the Third Battle of the Aisne, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and other areas. The 146th and 148th of the 66th Field Artillery Brigade were attached as corps artillery units and participated in the battles of Château-Thierry, Aisne-Marne, St Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne.

World War II

Preparation

|

1940 ("Square") Organisation

|

| Stanton, Order of Battle, U.S. Army World War II, p. 126 |

In 1921, the 41st Division was allocated to Pacific Northwest states. Its units returned to National Guard status but retained divisional organization. Each state was instructed to form divisional units.

Major General George A. White was appointed to command of the division in 1929 and eventually led it into World War II. As the international situation worsened in the 1930s, the intensity and urgency of training in the 41st increased. In 1937, the 41st paired with the 3rd Division for Corps manoeuvres at Fort Lewis. In these manoeuvres, a "Blue Army" drawn from the 41st Division attempted a combat crossing of the Nisqually River, which was defended by a "Red Army" under the command of Brigadier General George Marshall, then the commander of the 5th Infantry Brigade at Vancouver Barracks. The 41st Division's mission was accomplished by a night crossing of the river.[2]:1

The 41st Division's annual summer camp at Fort Lewis in June and July 1940 was extended from two weeks to three,[2]:1 and on 16 September 1940 with President Franklin D. Roosevelt's signing of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, the 41st Division was inducted into federal service for one year. By this time, a National Guard recruiting campaign had raised the strength of the division to 14,000 – still well short of its war establishment strength of 18,500.[2]:3 The difference was made up by 7,000 selective service men, the first of whom arrived in February 1941.[2]:5

The division was initially accommodated in a tented camp known as Camp Murray until the construction of new permanent accommodation nearby Fort Lewis could be completed.[2]:3 Delayed by strike action at sawmills in Washington and Oregon and by maritime workers, the project fell behind schedule,[3] and the entire division was not accommodated in the new barracks until April 1941.[2]:6

The 41st Division was grouped with the 3rd Division as part of IX Corps. In May 1941, the two divisions moved to the Hunter Liggett Military Reservation where June war games pitted them against Major General Joseph Stilwell's 7th Division and the 40th Division. Large scale manoeuvres continued in August on the Olympic Peninsula, with IX Corps defending Tacoma, Washington until the two divisions from California could arrive to assist.[2]:9–11

General White died on 23 November 1941 and was replaced by Brigadier General Horace H. Fuller, the former commander of the 3rd Division Artillery.[2]:12 Promoted to Major General on 15 December 1941, he would remain commander until June 1944.[2]:191

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 41st Infantry Division was deployed to defend the coastline of Washington and Oregon against a possible Japanese landing.[2]:17 The 218th Field Artillery was at sea en route to the Philippines; it was turned back to San Francisco and eventually rejoined the division.[2]:19

|

1942 ("Triangular") Organisation

|

| Stanton, Order of Battle, U.S. Army World War II, p. 127 |

The 41st Division was officially renamed the 41st Infantry Division on 2 August 1941.[2]:9 In January and February 1942, it was reorganised as a "triangular" division, losing the 161st Infantry, which eventually joined the 25th Infantry Division, and other units.[2]:19–21

Deployed overseas

In February 1942, the 41st Infantry Division was alerted for overseas movement. It handed over its coastal defence responsibilities to the 3rd Infantry Division and concentrated at Fort Lewis. First to depart was the 162nd Infantry, 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and 41st Reconnaissance Troop, which entrained later that month for Fort Dix. This group departed the Brooklyn Navy Yard on 3 March 1942 and sailed for the Pacific via the Panama Canal, reaching Melbourne on 9 April. They were among the first U.S. military units to be engaged in offensive ground combat operations. (The others were the 32nd who preceded them into combat on New Guinea, the Americal and the 1st Marine on Guadalcanal, Carlson's Raiders on Makin Island, and the 9th, 3rd Infantry and the 2nd Armored Divisions who fought in North Africa.)

A second group consisting of Division Headquarters, the 163rd Infantry, 41st Signal Company, 116th Engineer Battalion, 167th Field Artillery Battalion, 116th Medical Battalion, and 116th Quartermaster Battalion embarked from San Francisco on 19 March in a convoy that included the liner RMS Queen Elizabeth. This convoy reached Australia before the first, on 6 April. Because Melbourne could not accommodate the Queen Elizabeth, it unloaded at Sydney and the troops and cargo were moved to Melbourne by rail and smaller Dutch ships. That month the remainder of the division, including the 186th Infantry and 146th, 205th and 218th Field Artillery battalions entrained at Fort Lewis for San Francisco, from whence they sailed for Australia, arriving on 13 May. As each contingent arrived it moved to a camp near Seymour, Victoria, where training was conducted at the nearby Australian Army base at Puckapunyal.[2]:22–27

In July the division moved by rail to Rockhampton, Queensland.[2]:27[4] The division had arrived in Australia with a reputation as "the top ranking National Guard division and one of the three top divisions in the whole Army",[2]:6 a reason for its early deployment.

Major General Robert L. Eichelberger, whose I Corps headquarters arrived in Rockhampton in August, ordered the division to commence training in jungle warfare.[5]:39 Each infantry battalion in turn was sent down to Toorbul, Queensland for training in amphibious warfare by the Australian Army.[2]:28

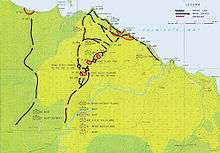

Sanananda

In December, General Douglas MacArthur decided to commit more American troops to the Battle of Buna-Gona. The 163rd Regimental Combat Team, under the command of Colonel Jens A. Doe, was alerted on 14 December 1942.[2]:33[6] It arrived at Port Moresby on 27 December. The first elements, which included the 1st Battalion and regimental headquarters, flew over the Owen Stanley Range to Popondetta and Dobodura on 30 December, where they came under the command of Lieutenant General Edmund Herring's Advanced New Guinea Force.[7]: 329–330

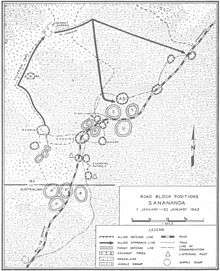

The 163rd Regimental Combat Team was attached to Major General George Alan Vasey's 7th Division and Doe assumed command of the positions on the Sanananda track from Brigadier Ivan Dougherty on 3 January 1943.[7]: 330 The front line consisted of a raised road with Japanese positions on relatively dry ground astride it, surrounded by jungle swamp. Roadblocks had been established behind the Japanese positions but they had not been budged; both sides resupplied their positions through the swamp. Vasey's plan was for the Americans to fix the Japanese in position while he attacked with Brigadier George Wootten's 18th Infantry Brigade, supported by M3 Stuart light tanks of the 2/6th Armoured Regiment and 25 pounders of the 2/1st Field Regiment.[7]: 332

Doe, "eager to come to close grips with the Japanese", requested permission to launch an attack against the enemy Perimeters Q and R between his two roadblocks. Herring and Vasey thought that he was underestimating the enemy, but Vasey gave permission for the attack, provided that it would not jeopardise the main plan.[8]:513 The attack went ahead on the afternoon of 8 January 1943 but both attacking companies of the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry encountered heavy fire and were thrown back. First Lieutenant Harold R. Fisk became the first officer of the division to be killed in action. His body could not be immediately recovered. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star. The roadblock position he had attacked from was named Fisk in his honour.[7]: 341

The first part of Vasey's plan involved the blocking of the Killerton Trail to prevent the Japanese from using it as an escape route, and to provide a jumping off point for a later advance by the 18th Infantry Brigade. The 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, under Major Walter R. Rankin, set out early on 9 January 1943. Company G, covering the flank of the advance, was strongly engaged by Japanese heavy machine gun, mortar, and rifle fire. The remainder of the battalion established themselves astride the trail in a new position which was named Rankin after the battalion commander. The attack had cost four dead and six wounded. More casualties would be taken holding the position over the next few day.[7]: 342

On 10 January, a patrol from the 163rd Infantry discovered that the Japanese had unaccountably evacuated Perimeter Q. This was occupied at once by Company A, which sent out tree snipers and patrols to harass the enemy and feel out the contour of the Perimeter R, which was now open to attack from all sides. The Japanese had left behind a considerable quantity of material, including a water-cooled .50 calibre machine gun. The Japanese had evidently been very hungry and there was evidence of cannibalism.[7]: 343

With the roadblock established, the 18th Infantry Brigade launched the main attack against Perimeter P on 12 January. Vasey's plan of attack was based on the assumption that the Japanese defenders had no antitank guns. This proved to be incorrect, and three Stuart tanks were hit by fire from a concealed 37mm anti-tank gun.[8]:515–516 Although the 2/9th and 2/12th Infantry Battalions killed some Japanese and gained some ground, the Japanese position remained intact. The attack cost 18th Infantry Brigade 34 killed, 66 wounded and 51 missing.[7]: 345

Wootten reported that to continue the attack under the existing conditions could only lead to heavy casualties. Vasey directed him to continue aggressive patrolling.[9]:232–233 They had completely misread the situation. On 14 January, a patrol from the 163rd Infantry captured a very sick Japanese soldier. Taken to 7th Division headquarters for interrogation, the man revealed that the Japanese commander, Lieutenant Colonel Tsukamoto Hatsuo, had ordered all able bodied men to evacuate Perimeter P, leaving the sick and wounded to hold it to the last.[2]:38 Vasey ordered an immediate attack. Supported by a troop of the 2/1st Field Regiment and their own mortars, Rankin's 2nd Battalion reduced the three small enemy perimeters to the south of their position and advanced to meet the Australians on the Killerton Track. By early afternoon the Australians and Americans had also joined hands on the Sanananda Road as well. Some 152 Japanese were killed and six captured.[7]: 348

On 15 January, a platoon of A Company managed to get inside Perimeter R undetected. The rest of the company followed, taking the Japanese defenders by surprise. Company C joined in the attack from the Fisk while Company B attacked from the west. Bunker after bunker fell to small groups attacking with rifles, grenades and submachine guns but the Japanese resistance was desperate and the entire position was not taken until the next day.[2]:39

The Australians carried out a wide envelopment, reaching the sea on 16 January, but the 163rd Infantry remained confronted by Perimeters S, T, and U, although these were not immediately located. A first attack succeeded in establishing a new position called AD.[2]:39 On 19 January an attack supported by 250 25 pounder and 750 M1 Mortar rounds faltered after a Japanese mortar round killed Company I's commander, Captain Duncan V. Dupree and its First Sergeant, James W. Boland.[7]:361 In his situation report, under "American troops", Vasey wrote "Heb. 13:8" ("Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, today and for ever.") But the next day, Companies A and K managed to fight their way into Perimeter T. This softened resistance from Perimeter S, and Companies B and C were then able to capture it. Some 525 Japanese dead were counted after the attack. Finally, on 22 January, Companies I and L were able to capture Perimeter U, counting another 69 Japanese dead.[2]:40

In just three weeks of fighting in January 1943, the 163rd Infantry lost 85 killed, 16 other deaths, 238 wounded and 584 sick, a total of 923 casualties.[10]

Salamaua

The 162nd Infantry, commanded by Colonel A. R. MacKechnie, ended its long period of waiting and got its baptism of fire in early 1943. The fight, which resulted in the fall of Salamaua and Lae, lasted for 76 days after the initial landing. The Presidential unit citation awarded the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry Regiment, reads "for outstanding performance of duty against the enemy near Salamaua, New Guinea. On 29 and 30 June 1943, this battalion landed at Nassau Bay in one of the first amphibious operations by American forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, on a beach held by the enemy, and during a severe storm which destroyed 90 percent of the landing craft able to reach the beach. Moving inland through deep swamps, crossing swift rivers, cutting its way through dense jungle, over steep ridges, carrying by hand all weapons, ammunition, and food, assisted by only a limited number of natives, this battalion was in contact with the enemy for 76 consecutive days without rest or relief. All operations after the initial landing were far inland. Living conditions were most severe because of constant rain, mud, absence of any shelter, tenacious enemy, and mountainous terrain. The supply of rations, ammunition and equipment was meager. For five weeks all personnel lived on rations dropped by airplane, for days at a time on half rations. Malaria and battle casualties greatly depleted their ranks, but at no time was there a let-up in morale or in determination to destroy the enemy. Each officer and enlisted man was called upon to give his utmost of courage and stamina. The battalion killed 584 Japanese during this period, while suffering casualties of 11 officers and 176 enlisted men. Cutting the Japanese supply line near Mubo, exerting constant pressure on his flank, the valiant and sustained efforts of this battalion were in large part instrumental in breaking enemy resistance and forcing his withdrawal from Salamaua on 12 September 1943. General Orders 91."[2]:183

Hollandia

The 41st Infantry Division returned to Australia for rest, reinforcements, and re-equipping. By April 1944, they had assembled an armada of a hundred ships carrying 25,000 men and tons of equipment for an attack on the Humboldt Bay area of New Guinea to secure Japanese-held airfields. A massive naval bombardment was followed by air strikes to soften the area for the amphibious landing. The 162nd Infantry moved north to overrun its objective, Hollandia Town, while the 186th Infantry moved west to capture two airdromes. On the second day, a low-flying enemy bomber made a direct hit on a Japanese ammunition dump. The subsequent explosions ignited a two-day firestorm that consumed all American ammunition and rations landed in that beach area, and caused 24 deaths and over 100 injuries. Rationing became necessary. Soft sand bogged tanks, and LVTs became mired along swampy roads. The terrain was favorable for the Japanese defensive, but most of their troops had moved to Wewak, where they expected the next Allied thrust. As a result, casualties were light. High-ranking Army and Navy officers who had witnessed the landing described it as the perfect amphibious assault."[2]:77–87

Aitape

While the 162nd Infantry and 186th Infantry were making the landings in Humboldt Bay, the 163rd Regimental Combat Team, backbone of a task force of 22,500 men under the command of General Doe, was making a simultaneous landing at Aitape. The mission of this force was to rapidly seize the airdromes in the Aitape-Tadji area and to prepare these airfields quickly to accommodate one fighter group. The naval bombardment was so well executed that the enemy fled inland. The advance was so rapid that engineer units pronounced the captured airstrip ready for use two days after the landing. Some enemy resistance was encountered by patrols, but was pushed back effectively. On 3 May the 163rd was relieved by the 32nd Division.[2]:89–92

Wakde Island

Occupation of Wakde was to be a shore-to-shore operation. It was too small an island to permit a major landing force. Following a naval bombardment on 17 May, the 163rd Infantry landed four companies (A,B,C and F), seized the beachhead and began the push inland assisted by four Sherman medium tanks. The companies executed a successful flanking maneuver which left the important airfield in the middle of the island in Allied control after only two days of fighting. The campaign was unique for its brevity and conclusiveness, and marked the first time that terrain and conditions permitted the full use of tanks.

Biak

The 41st Division's bloodiest engagement was on the island of Biak, off New Guinea's coast. It marked the first time the division had fought as a whole, and resulted in the defeat of over ten thousand well-entrenched and well-led Japanese forces. The campaign extended from May through August 1944, and the 41st earned a new nickname, "The Jungleers." The first tank battle of the Pacific Theater occurred on Biak, when Japanese Type 95 Ha Go tanks attempted to attack the beachhead. They were destroyed by US Army M4 Sherman tanks. Casualties on Biak were 435 Americans KIA and 2,360 WIA. The Japanese lost an estimated 6,125 KIA, with 460 POWs, and 360 Formosan POWs. After finally securing the island, American troops developed southern Biak into a large airbase and staging area. Biak contained three aerodromes; Mokmer, Borokoe and Sorido. The capture of Mokmer Drome was particularly challenging due to the proximity of cliffs of coral that provided very strategic cover for Japanese heavy guns. Because the 41st failed to repeat the swift progress made in prior landngs, General Fuller was relieved as commander of Hurricane Task Force. Continuous heavy fighting, intense heat and scarcity of water had tired the task force troops to a critical degree. General Eichelberger and General Doe were to prove able successors, but it took until 20 August to officially terminate a campaign that had begun with beach landings on 27 May 1944.

Palawan

The 186th Regimental Combat Team stormed ashore on 28 February 1945 in the first action in the Philippine Islands. Among the Filipino regular and constable troops of the Philippine Commonwealth Army and Philippine Constabulary on the mainland in Palawan were aided on the oppositions against the Japanese. The airfields were found to be unserviceable to the pre-landing bombardments, and the town of Puerto Princesa was mostly destroyed. However, in three years of campaigning, this was the first semblance of civilization. American casualties were 12 killed and 56 wounded. Filipino casualties were 55 killed and 120 wounded. Japanese losses were 890 dead and 20 POWs. The operation terminated on 20 June 1945.

Zamboanga

Zamboanga, and the Sulu Archipelago. The Division was aided by the Filipino ground force under the Philippine Commonwealth Army and Philippine Constabulary are operates against the enemy. The massive assault began with naval and air bombardments along the beach defenses east of Zamboanga City, forcing the enemy to evacuate these excellent defensive positions. The 162nd and 163rd Infantry Regiments made their landings, and the enemy fled into the hills in disorder. A series of counterattacks faced the Jungleers, but they prevailed despite well-established hill positions, which were overrun by 24 March. By the end of March, the 186th Infantry had rejoined the Division and relieved elements of the 163rd, who proceeded to the island of Jolo, followed by more island-hopping to Tawi-Tawi. The conquest of the entire Sulu chain of islands left just mopping up to be done. The Southern Philippines had been freed from Japanese oppression.

End of the war and 0ccupation of Japan

After the fall of the Philippines, the division began training for the attack on Japan itself, but surrender came first. The division did move to Japan where it occupied the island of Honshū for a few months. The 41st Infantry Division was inactivated at Kure-Hiro, Japan on 31 December 1945.

World War II casualties

- Total battle casualties: 4,260[11]

- Killed in action: 743[12]

- Wounded in action: 3,504[13]

- Missing in action: 13[14]

Post war

The 41st Infantry Division was reformed in Oregon in 1946. In 1965 it was reorganised as the 41st Infantry Brigade. The 41st Infantry Division was inactivated in 1968.

The 41st Infantry Division holds annual reunions for its World War II veterans. In 2008 the reunion was held in Washington, D.C. The veterans had the opportunity to visit Arlington National Cemetery and hold a special wreath laying ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Many of the veterans also visited the World War II memorial for the first time. Several were accompanied by family (including spouses, children, grandchildren, and in a couple of cases, great grandchildren). The Jungeleer is the publication of the 41st Infantry and is available to all former members of this division.

Commanders

World War I

- Major General Hunter Liggett (18 September 1917)

- Brigadier General Henry Jervey (20 September 1917)

- Brigadier General G. LeR. Irwin (12 December 1917)

- Major General Hunter Liggett (20 December 1917)

- Brigadier General LeR. Irwin (18 January 1918)

- Brigadier General Richard Coulter, Jr. (23 January 1918)

- Brigadier General Robert Alexander (14 February 1918)

- Brigadier General Edward Vollrath (3 August 1918)

- Brigadier General W. S. Scott (19 August 1918)

- Major General J. E. McMahon (21 October 1918)

- Brigadier General Edward Vollrath (24 October 1918)

- Brigadier General Eli K. Cole, USMC (29 October 1918)

- Brigadier General Edward Vollrath (27 December 1918)

- Major General Peter E. Traub (29 December 1918)

World War II

- Major General George A. White (3 January 1930)

- Brigadier General Carlos A. Pennington (23 November 1941)

- Major General Horace H. Fuller (2 December 1941)

- Major General Jens A. Doe (18 June 1944)

- Major General Ralph S. Phelps April 1963-September 1968 (last commanding Major General). General Phelps was also the commanding officer of the first Army Ski Patrol established in 1941 at Camp Murray which later became the 10th Mountain Division. He joined the 41st in 1938 as a private.

Notes

- ↑ McGrath, 'The Brigade,' p.170

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 McCartney, Wiliam F. (1948). The Jungleers: A History of the 41st Infantry Division. Washington, D.C.: Infantry Journal Press. ISBN 1-4325-8817-6.

- ↑ Fine and Remington, Construction in the United States, p. 217

- ↑ Dunn, Peter. "CAMP CAVES NEAR ROCKHAMPTON, QLD". www.ozatwar.com. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ Shortal, John Francis (1987). Forged by Fire: Robert L. Eichelberger and the Pacific War. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-521-3. OCLC 16356063.

- ↑ About 3,800 strong, the unit consisted of the 163rd Infantry; Company E, 116th Engineer Battalion; Company E 116th Medical Battalion; the 7th, 11th and 12th Portable Surgical Hospitals; and detachments of the 41st Signal Company, 41st Ordnance Company, 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion and 116th Quartermaster Company.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Milner, Samuel (1972). Victory in Papua. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Dudley (1959). "South-West Pacific Area – First Year". Australia in the War of 1939–45.

- ↑ Horner, David (1992). General Vasey's War. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84462-6. OCLC 243778546.

- ↑ Papuan Campaign, p. 82.

- ↑ Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ↑ Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ↑ Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ↑ Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

References

- The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950. Reproduced at the United States Army Center of Military History.

- Fine, Lenore; Remington, Jesse A. (1972). "The Corps of Engineers: Construction in the United States". Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- Horner, David (1992). General Vasey's War. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84462-6. OCLC 243778546.

- McCarthy, Dudley (1959). "South-West Pacific Area – First Year". Australia in the War of 1939–45.

- McCartney, Wiliam F. (1948). The Jungleers: A History of the 41st Infantry Division. Washington, D.C.: Infantry Journal Press. ISBN 1-4325-8817-6.

- Milner, Samuel (1972). Victory in Papua. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- Shortal, John Francis (1987). Forged by Fire: Robert L. Eichelberger and the Pacific War. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-521-3. OCLC 16356063.