474th Searchlight Battery, Royal Artillery

| 474th Searchlight Battery, RA | |

|---|---|

|

Royal Artillery cap badge and AA patch | |

| Active | 1940–1946 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Searchlight Battery |

| Role |

Air Defence Movement light |

| Garrison/HQ | Edinburgh |

| Engagements |

Battle of Britain The Blitz Operation Overlord Operation Market Garden Operation Veritable Operation Plunder |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Major Duncan Mackay Weatherstone, MC |

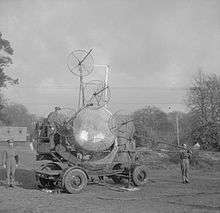

474th Searchlight Battery, Royal Artillery was a unit of the British Army during World War II. Originally raised as an anti-aircraft (AA) battery, in which role it served during the Battle of Britain and Blitz, it also provided artificial illumination, or 'Monty's Moonlight', for night operations by 21st Army Group during the campaign in North West Europe in 1944–45.

Origin

474th Searchlight Battery was formed in the Royal Artillery (RA) in 1940, based on a cadre drawn from two Scottish searchlight (S/L) units based in Edinburgh, the 51st (Highland) Anti-Aircraft Battalion, Royal Engineers (2 officers and 19 other ranks) and 4/5th Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment), (52nd Searchlight Regiment) (5 officers and 27 other ranks). In February the cadres travelled down to 222nd Searchlight Training Regiment, RA, at Norton Manor Barracks near Taunton where, together with 235 conscripts and 83 volunteers, they formed a new battery on 1 March. The battery did not form part of a regiment, but was assigned to 5th Anti-Aircraft Division to be attached as required.[1]

Battle of Britain

By mid-March, the battery had moved to the Tetbury area, with HQ at Manor Farm, Westonbirt, taking over existing searchlight sites and equipment from 455th Company, 1st (Rifles) Battalion, The Monmouthshire Regiment (68th Searchlight Regiment). The new battery came under the orders of that regiment, but within a month it moved to Kings Worthy in Hampshire and came under the command of 4th Battalion, Queen's Royal Regiment (63rd Searchlight Regiment)) in 47th AA Brigade. It was controlled by the operations room at RAF Tangmere and formed part of the AA defences for Southampton. Here the battery underwent training and began to receive the powerful new 150 cm searchlight to supplement the standard 90 cm equipment. From the beginning of June there were almost nightly alerts as the Battle of Britain got under way, and on the night of 18/19 June several Luftwaffe bombers were picked up by searchlights of 63rd Rgt and destroyed by AA guns and night fighters.[1][2][3][4][5]

On 3 July 1940 the battery was transferred from 63rd S/L Rgt to 3rd (Ulster) S/L Rgt, just returned from the Dunkirk evacuation, but three weeks later it was ordered to hand over its sites to another battery of 3rd S/L Rgt and move to Cornwall where it joined the newly formed 76th S/L Rgt under 55th AA Bde. Battery Headquarters was at Redruth, later at Killiow, and when the last of the Troops arrived from Hampshire in late August the battery occupied a full establishment of 24 S/L sites.[1][6][7]

In August 1940, all army searchlight units, whether Royal Artillery (RA), Royal Engineers (RE), or still forming parts of infantry regiments, were brought under the RA.[6][8][9]

The Blitz

In November 1940, during The Blitz, 474th Battery moved again, to Sherborne in Dorset, where 76th S/L Rgt came under 64th AA Bde in 8th AA Division, both being new formations created in the rapidly expanding Anti-Aircraft Command. The brigade's prime responsibility was airfield defence.[1][2][10][11]

In January 1941 the battery moved to Alderbury in Wiltshire, but its role was unchanged. It began to receive GL Mark I E/F gun-laying radar equipped with elevation-finding equipment. It was also engaged in experiments at RAF Boscombe Down to see how searchlights combined with AA guns could deal with low-flying attacks. By the spring the battery manned clusters of three searchlights at Boscombe Down and RAF Middle Wallop.[1][12]

Mobile role

After the Blitz ended in May 1941, the battery continued its home defence role in AA Command until the beginning of 1943. In February 1943 it moved to Thurstaston and deployed its detachments to 24 AA and anti-minelaying sites on the Mersey and round Barrow-in-Furness and Walney Island. At this point 474 Bty ceased to be part of 76th S/L Rgt and became an independent unit, though coming under the operational command of HQ 39th (Lancashire Fusiliers) S/L Rgt, which had no other batteries under its command.[13][14] In April the battery handed over its sites to 356th (Ind) S/L Bty and moved to Kinross in Scotland to train in mobile operations. 474th (Ind) S/L Bty was formally mobilised for active service in June 1943 and in August was joined by its own Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) workshop, which had formed at Bestwood Camp, Nottingham in May as 'M' S/L Battery Workshop.[13][15]

After attending various training camps and field exercises, the battery moved to Silverstone in Northamptonshire and joined 100 AA Bde, one of the formations preparing for Operation Overlord, the planned Allied invasion of Normandy.[13][16] In February 1944, Battery HQ moved to Caterham in Surrey, where it came under the command of 80 AA Bde, one of the Overlord assault formations, though Troops of 8 lights were detached until April, providing 'Canopy' cover for RAF Colerne and RAF Manston.[16]

Normandy

The battery's reconnaissance and assault groups embarked on 1 June, and the first part of C Troop disembarked on Juno Beach at 14.00 on D-Day (6 June). However, attempts to land four S/L lorries of C Troop later in the day led to three becoming submerged, and offloading of equipment did not restart until the following day at Juno and Sword Beaches, still under fire. By the end of D + 1 the battery had three lights in action against enemy raiders.[17][18] It was under command of 80 AA Bde, initially responsible for covering 3rd Canadian Division at Juno and 3rd British Division at Sword, later extended to include the port of Ouistreham and the Orne and Caen canal bridges.[18][19][20]

Over succeeding days the battery brought more lights into action (16 by D + 4), but engagements were difficult because of the low cloud, the haphazard directions from which raiders approached, and their use of 'Window' to interfere with searchlight control (SLC) radar. The S/L sites were also subject to occasional shelling and bombing, causing some casualties. Nevertheless, the lights did assist the AA guns in the beachhead to destroy a number of bombers.[17][21]

From early July, the battery was regularly called upon to send detachments to provide 'artificial moonlight' for troops in forward areas.[17] This was a new technique being developed to reflect light off the cloudbase to provide 'movement light' (also known as 'Monty's moonlight') in support of night operations. 344th and 356th Independent S/L Batteries pioneered this technique using their mobile 90 cm searchlights.[22] It was first used operationally to assist the assembly of troops for Operation Greenline on the night of 14/15 July, when the drivers of 15th (Scottish) Division 'found the light a great help to them in finding their way up the pot-holed track through the blinding dust'.[23]

Low Countries

On 22 August, as the Allied breakout from the Normandy beachhead got under way, A Troop was withdrawn from its sites and attached to 71st Light AA Regiment for the drive to the Seine. On 26 August the troop deployed its lights at Vernon, to defend the bridges under construction where 43rd (Wessex) Division had made an assault crossing of the river the previous day.[17][24][25][26] On 4 September the rest of the battery arrived at Vernon. However, 21st Army Group was now advancing rapidly across northern France, and A Troop moved up via Amiens and Douai while the rest of the battery deployed round Rouen on 10 September. By 14 September the battery was in Brussels and on 21 September it completed a 320-mile advance, with several moonlight and AA deployments along the way, including supporting the canal crossing at Joe's Bridge. A Troop reached Nijmegen to deploy for AA defence of the vital bridges shortly after their capture in Operation Market Garden, the rest of the battery guarding bridges further back. The Nijmegen bridge defences were shelled and mortared as well as attacked by low-level bombers – 16 raids on 26 September and nine more the following day. A Troop was assigned to AA defence north and south of the river, as well as illuminating the river, where German Frogmen succeeded in damaging the bridges.[17][18][27][28]

During the winter of 1944–45, while A Troop experimented with using SLC radar to direct LAA guns, the rest of 474 S/L Bty was frequently deployed in detachments to provide movement light to various formations – for example, for laying or lifting minefields, bridgebuilding, or fighting patrols. A major deployment was with VIII Corps for Operation Veritable in the Reichswald.[17][29][30] However, unlike some other batteries engaged in the same work, its official designation was not changed from 'Searchlight' to 'Moonlight', and at the Rhine crossing (Operation Plunder) it reverted to the AA role, forming part of 100 AA Bde supporting XII Corps.[29][31]

Germany

Once the first Rhine bridge was completed on 25 March 1945, 474 Bty moved up to the west bank of the river to take up its positions. That night there was a series of raids by single Luftwaffe bombers at heights up to 8000 feet, where S/L illumination permitted the AA guns to fire predictor-controlled shoots. After 27 March, with 21st Army Group pushing deep into Germany, air attacks on the Rhine crossings became fewer. By now the crossing points were covered by integrated systems of heavy and light AA guns, radar and S/L positions, which prevented accurate attacks and destroyed a significant number of aircraft.[29][32]

In mid-April the battery handed over its S/L responsibilities at the Rhine crossings and began carrying out rear-area duties such as guarding and clearing ammunition dumps. It continued this battlefield clearance work after the German surrender at Lüneburg Heath on 7 May, and also provided artificial moonlight at prisoner of war and refugee camps. At the end of 1945 the battery was stationed at Dortmund and completed its disbandment on 1 January 1946.[29][33]

Prominent members

- The first commanding officer of the battery was Captain (acting Major) Duncan Mackay Weatherstone (1898–1972), who had won a Military Cross (MC) with the 17th (Service) Bn Royal Scots during World War I.[1][34][35] An insurance manager, he became Lord Provost of Edinburgh (1963–66) and was knighted in 1965.[36][37] After remarrying, to a woman 41 years his junior, he got into debt and they committed double suicide in 1972.[38][39]

- Captain Arthur McLaurin Edmonds received an MC after the war, the citation mentioning his bravery during the Normandy landings in unloading a broken-down Rhino ferry under heavy fire. Later he led the detached A Troop at the Caen Canal, in moonlight duties, and at the Rhine crossing.[18]

- Serjeant Daniel Tosh received a Military Medal (MM) after the war, the citation mentioning his bravery on D-Day, his work in evacuating casualties from a shelled S/L site at Nijmegen, and supplying his men there by rowing boat while the road bridge was under repair.[40]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 474 S/L Bty War Diary, 1940–41, The National Archives (TNA), Kew file WO 166/3322.

- 1 2 Farndale, AnnexD.

- ↑ Routledge, p. 55.

- ↑ 68 S/L Rgt at RA 39–45.

- ↑ 63 S/L Rgt at RA 39–45.

- 1 2 Farndale, Annex M.

- ↑ 3 S/L Rgt at RA 39–45.

- ↑ Litchfield, p. 5.

- ↑ Routledge, p. 78.

- ↑ Routledge, Table LXV, p. 396.

- ↑ 8 AA Division at British Military History.

- ↑ Routledge, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 474 (Ind) S/L Bty War Diary, 1943, TNA file WO 166/11557.

- ↑ 39 S/L Regt War Diary, 1943, TNA file WO 166/11500.

- ↑ 474 S/L Bty Workshop War Diary, 1943, TNA file WO 166/13067.

- 1 2 474 (Ind) S/L Bty War Diary, January–June 1944, TNA file WO 166/14909.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 474 (Ind) S/L Bty War Diary, June–December 1944, TNA file WO 171/1213.

- 1 2 3 4 Medal citation for Capt A.M. Edmonds, TNA file WO 373/56/625.

- ↑ Routledge, pp. 308–11; Table XLIX, p. 319.

- ↑ Joslen, p. 583.

- ↑ Routledge, pp. 310–2.

- ↑ Routledge, pp. 314, 317.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 66–9.

- ↑ Routledge, p. 320, Table L, p. 327.

- ↑ Ellis, p. 466.

- ↑ Ford.

- ↑ Routledge, pp. 324–5.

- ↑ 474 S/L Bty at RA Netherlands.

- 1 2 3 4 474 (Ind) S/L Bty War Diary, 1945, TNA file WO 171/5102.

- ↑ Routledge, p. 350.

- ↑ Routledge, Table LVI, p. 365.

- ↑ Routledge, pp. 354–60.

- ↑ 474 (Ind) S/L Bty War Diary, January 1946, TNA file WO 171/9191.

- ↑ Medal card of Duncan Mackay Weatherstone, TNA file WO 372/21/52442.

- ↑ Monthly Army List, December 1918.

- ↑ London Gazette 12 June 1965.

- ↑ Who Was Who 1971–1980.

- ↑ Glasgow Herald, 7 February 1972.

- ↑ Kenneth Roy, The Invisible Spirit: A life of Post-War Scotland 1945–72, Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2015 ISBN 9780857908117.

- ↑ Medal citation for Sjt D. Tosh, TNA file WO 373/56/84.

References

- Major L. F. Ellis, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: Victory in the West, Vol I: The Battle of Normandy, London: HM Stationery Office, 1962/Uckfield: Naval & Military, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-58-0.

- Gen. Sir Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: The Years of Defeat: Europe and North Africa, 1939–1941, Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1988/London: Brasseys, 1996, ISBN 1-85753-080-2.

- Ken Ford, Assault Crossing: The River Seine 1944, 2nd Edn, Bradford: Pen & Sword, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84884-576-3

- Lt-Col H. F. Joslen, Orders of Battle, United Kingdom and Colonial Formations and Units in the Second World War, 1939–1945, London: HM Stationery Office, 1960/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2003, ISBN 1-843424-74-6.

- Norman E. H. Litchfield, The Territorial Artillery 1908–1988 (Their Lineage, Uniforms and Badges), Nottingham: Sherwood Press, 1992, ISBN 0-9508205-2-0.

- Brig N. W. Routledge, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: Anti-Aircraft Artillery 1914–55, London: Royal Artillery Institution/Brassey's, 1994, ISBN 1-85753-099-3