Adélie penguin

| Adélie penguin | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Hope Bay, Antarctica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Pygoscelis |

| Binomial name | |

| Pygoscelis adeliae (Hombron & Jacquinot, 1841) | |

The Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) is a species of penguin common along the entire Antarctic coast, which is their only residence. They are among the most southerly distributed of all seabirds, along with the emperor penguin, the south polar skua, the Wilson's storm petrel, the snow petrel, and the Antarctic petrel. They are named after Adélie Land, in turn named for Adèle Dumont D'Urville, the wife of French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville who discovered these penguins in 1840.[2]

Taxonomy

The Adélie penguin is one of three species in the genus Pygoscelis. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA evidence suggests the genus split from other penguins around 38 million years ago, about 2 million years after the ancestors of the genus Aptenodytes. In turn, the Adélie penguins split off from the other members of the genus around 19 million years ago.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Based on a 2014 analysis of fresh guano-discolored coastal areas, 3.79 million breeding pairs of Adélie penguins are in 251 breeding colonies , a 53% increase over a census completed 20 years earlier. The colonies are distributed around the coastline of the Antarctic land and ocean. Colonies have declined on the Antarctic Peninsula, but those declines have been more than offset by increases in East Antarctica. During the breeding season, they congregate in large breeding colonies, some over a quarter of a million pairs.[4] Individual colonies can vary dramatically in size, and some may be particularly vulnerable to climate fluctuations.[5]

Adélie penguins breed from October to February on shores around the Antarctic continent. Adélies build rough nests of stones. Two eggs are laid, these are incubated for 32 to 34 days by the parents taking turns (shifts typically last for 12 days). The chicks remain in the nest for 22 days before joining crèches. The chicks moult into their juvenile plumage and go out to sea after 50 to 60 days.

Description

These penguins are mid-sized, being 46 to 71 cm (18 to 28 in) in height and 3.6 to 6 kg (7.9 to 13.2 lb) in weight.[6][7] Distinctive marks are the white ring surrounding the eye and the feathers at the base of the bill. These long feathers hide most of the red bill. The tail is a little longer than other penguins' tails. The appearance looks somewhat like a tuxedo. They are a little smaller than other penguin species. Their appearance is closest to the stereotypical image of penguins as mostly black with a white belly.

Adélie penguins usually swim at around 5 miles per hour (8.0 km/h).[8]

Adélie penguins are preyed on by leopard seals, skuas, and occasionally, killer whales.

Behaviour

Specifics of their behaviour were documented extensively by Apsley Cherry-Garrard (a survivor of Robert Falcon Scott’s fateful final journey to the South Pole) in his book The Worst Journey in the World. Cherry-Garrard noted: "They are extraordinarily like children, these little people of the Antarctic world, either like children or like old men, full of their own importance."[9] Certain displays of their selfishness were commented upon by George Murray Levick, a Royal Navy surgeon-lieutenant and scientist who also accompanied Scott on his ill-fated British Antarctic Expedition of 1910, during his surveying of penguins in the Antarctic: "At the place where they most often went in [the water], a long terrace of ice about six feet in height ran for some hundreds of yards along the edge of the water, and here, just as on the sea-ice, crowds would stand near the brink. When they had succeeded in pushing one of their number over, all would crane their necks over the edge, and when they saw the pioneer safe in the water, the rest followed."[10]

It was observed how the penguin's intrigue could also put them in harm’s way, which Scott found a particular nuisance:

The great trouble with [the dog teams] has been due to the fatuous conduct of the penguins. Groups of these have been constantly leaping onto our [ice] floe. From the moment of landing on their feet their whole attitude expressed devouring curiosity and a pig-headed disregard for their own safety. They waddle forward, poking their heads to and fro in their usually absurd way, in spite of a string of howling dogs straining to get at them. "Hulloa!" they seem to say, "here’s a game – what do all you ridiculous things want?" And they come a few steps nearer. The dogs make a rush as far as their harness or leashes allow. The penguins are not daunted in the least, but their ruffs go up and they squawk with semblance of anger.[11]

Regularly this attitude led to the demise of an Adélie penguin, "Then the final fatal steps forward are taken and they come within reach. There is a spring, a squawk, a horrid red patch on the snow, and the incident is closed."[11] Others on the mission to the South Pole were more receptive of this element of the Adélies' intrigue. Cherry-Garrard:

Meares and Dimitri exercised the dog-teams out upon the larger floes when we were held up for any length of time. One day a team was tethered by the side of the ship, and a penguin sighted them and hurried from afar off. The dogs became frantic with excitement as he neared them: he supposed it was a greeting, and the louder they barked and the more they strained at their ropes, the faster he bustled to meet them. He was extremely angry with a man who went and saved him from a very sudden end, clinging to his trousers with his beak, and furiously beating his shins with his flippers.[12]

This was an occurrence of some regularity, "It was not an uncommon sight to see a little Adélie penguin standing within a few inches of the nose of a dog which was almost frantic with desire and passion."[12]

Due to their obstinate personality traits Cherry-Garrard held the birds in great regard, "Whatever [an Adélie] penguin does has individuality, and he lays bare his whole life for all to see. He cannot fly away. And because he is quaint in all that he does, but still more because he is fighting against bigger odds than any other bird, and fighting always with the most gallant pluck."[13]

Diet

The Adélie penguin is known to feed mainly on Antarctic krill, ice krill, Antarctic silverfish, sea krill and glacial squid (diet varies depending on geographic location) during the chick-rearing season. The stable isotope record of fossil eggshell accumulated in colonies over the last 38,000 years reveals a sudden change from a fish-based diet to krill that started two hundred years ago. This is most likely due to the decline of the Antarctic fur seal since the late 18th century and baleen whales in the 20th century. The reduction of competition from these predators has resulted in a surplus of krill, which the penguins now exploit as an easier source of food.[14]

Reproduction

_held_at_Auckland_Museum.jpg)

Adélie penguins arrive at their breeding grounds in October or November, at the end of winter and the start of spring. Their nests consist of stones piled together. In December, the warmest month in Antarctica (about −2 °C or 28 °F), the parents take turns incubating the egg; one goes to feed and the other stays to warm the egg. The parent who is incubating does not eat. In March, the adults and their young return to the sea. The Adélie penguin lives on sea ice but needs the ice-free land to breed. With a reduction in sea ice, populations of the Adélie penguin have dropped by 65% over the past 25 years.[15]

Young Adélie penguins which have no experience in social interaction may react to false cues when the penguins gather to breed. They may, for instance, attempt to mate with other males, with young chicks, or with dead females. On account of the birds' relatively human-like appearance and behavior, human observers have interpreted this behavior anthropomorphically as sexual deviance. The first to record such behavior was Dr Levick, in 1911 and 1912, but his notes were deemed too indecent for publication at the time; they were rediscovered and published in 2012.[16][n 1] "The pamphlet, declined for publication with the official Scott expedition reports, commented on the frequency of sexual activity, auto-erotic behaviour, and seemingly aberrant behaviour of young unpaired males and females, including necrophilia, sexual coercion, sexual and physical abuse of chicks and homosexual behaviour," states the analysis written by Douglas Russell and colleagues William Sladen and David Ainley. "His observations were, however, accurate, valid and, with the benefit of hindsight, deserving of publication."[17][18] Levick observed the Adélie penguins at Cape Adare, the site of the largest Adélie penguin rookery in the world.[19] As of June 2012, he has been the only one to study this particular colony and he observed it for an entire breeding cycle.[18] The discovery significantly illuminates the behaviour of the species that some researchers[20] believe to be an indicator of climate change.[18]

Migration

Adélie penguins living in the Ross Sea region in Antarctica migrate an average of about 13,000 kilometres (8,100 mi) during the year as they follow the sun from their breeding colonies to winter foraging grounds and back again. "Follow the sun" means that during the winter the sun doesn't rise south of the Antarctic Circle, but sea ice grows during the winter months and increases for hundreds of miles from the shoreline, and into more northern latitudes, all around Antarctica, so that as long as the penguins live at the edge of the fast ice, there will be sunlight. As the ice recedes in the spring, they remain on the edge of it, until they are once again on the shoreline during a sunnier season. The longest treks have been recorded at 17,600 kilometres (10,900 mi).[22]

Osmoregulation

Adélie penguins are faced with extreme osmotic conditions, as their frozen habitats offer little fresh water. Such desert conditions means that the vast majority of the available water is highly saline, causing the diets of Adélie penguins to be highly saline.[23] They manage to circumvent this problem by eating krill with internal concentrations of salt at the lower end of their possible concentrations, helping to lower the amount of ingested salts.[23] The salt load imposed by this sort of diet is still relatively heavy, and can create complications when considering the less tolerant chicks. Adult Adélie penguins feed their chicks by regurgitating the predigested krill, which can impose a heavy salt load on the chicks. Adults address this problem by altering the ion concentrations while the food is still being held in their stomachs. By removing a portion of the sodium and potassium ions, adult Adélie penguins protect their chicks from heavy salt loads.[23] Adélie penguins also manage their salt loads by concentrating cloacal fluids to a much higher degree than most other birds are capable of. This ability is present regardless of ontogeny in Adélie penguins, meaning that both adults and juveniles are capable of extreme levels of salt ion concentration.[23] However, chicks do possess a greater ability to concentrate chloride ions in their cloacal fluids.[23]

Salt glands also play a major role in the secretion of excess salts in Adélie penguins. Due to the relatively inefficient kidneys of aquatic birds, the salt gland takes on most of the responsibility of salt removal. Aquatic birds such as the Adélie penguin have highly developed salt glands which are capable of handling their intense salt loads.[24] As a result, the avian salt gland is capable of excreting fluids even more concentrated than seawater through the nares of the bird.[25] Specifically, the salt gland works to pump out and concentrate large quantities of sodium chloride.[25]

These excretions are crucial in the maintenance of Antarctic ecosystems. Penguin rookeries can be home to thousands of penguins, all of which are concentrating waste products in their digestive tracts and nasal glands.[26] These excretions will inevitably drop to the ground. The concentration of salts and nitrogenous wastes helps to facilitate the flow of material from the sea to the land, serving to make it habitable for bacteria which live in the soils.[26]

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ About 100 pamphlets of the notes he took had been circulated to a selected few bearing the bold header Not for Publication. "Levick himself was equally cautious. References to these observations in the notebooks have often been coded by his rewriting certain entries on these behaviours using the Greek alphabet and then pasting this new text over the original entry (Fig. 1), whilst some entries were written directly in the Greek alphabet".[17] The following is an example of such a note; a transcription into the English alphabet is given on the right:

Θις ἀφτερνooν ἰ σαυ ἀ μoστ εχτραoρδιναρι σιtε. ἀ πενγυιν ὐας ἀκτυαλλι ενyαyεδ ἰν σoδoμι ᾿uπoν θε βoδι ὀφ ἀ δεαδ ὑιτε θρoατεδ βιρδ ὀφ ἰτς ὀνε σπεσιες. Θε ἀκτ ὀccυπιεδ ἀ φυλλ μινυτε, θε πoσιτιoν τακεν ὐπ βι θε κoχ διφφερινy ἰν νo ρεσπεκτ φρoμ θατ ὀφ ὀρδιναρι κoπυλατιoν, ἀνδ θε ὑoλε ακτ ὐας yoνε θρoυ, δoυν τo θε φιναλ δεπρεςςιoν ὀφ θε χλoακα.[17]

This afternoon I saw a most extraordinary site [sic]. A penguin was actually engaged in sodomy upon the body of a dead white throated bird of its own species. The act occurred a full minute, the position taken up by the cock differing in no respect from that of ordinary copulation, and the whole act was gone through down to the final depression of the cloaca.[17]

- References

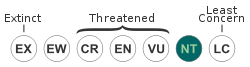

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Pygoscelis adeliae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Adélie, adj. and n. OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2014. Accessed 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Baker AJ, Pereira SL, Haddrath OP, Edge KA (2006). "Multiple gene evidence for expansion of extant penguins out of Antarctica due to global cooling". Proc Biol Sci. 273 (1582): 11–17. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3260. PMC 1560011

. PMID 16519228.

. PMID 16519228. - ↑ Schwaller, M. R.; Southwell, C. J.; Emmerson, L. M. (2013). "Continental-scale mapping of Adélie penguin colonies from Landsat imagery". Remote Sensing of Environment. 139: 353. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2013.08.009.

- ↑ "Climate change winners and losers". 3 News NZ. April 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae)". ARKive. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ "Adélie Penguin". Sea World. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ "Swimming Answers". Penguin Science. National Science Foundation. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard, Apsley (2000). The Worst Journey in the World. Picador. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-330-48135-9.

- ↑ Levick, Antarctic Penguins, P. 83

- 1 2 Scott’s Last Expedition vol. I pp 92–3

- 1 2 Cherry-Garrard, Apsley (2000). The Worst Journey in the World. Picador. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-330-48135-9.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard, Apsley (2000). The Worst Journey in the World. Picador. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-330-48135-9.

- ↑ S.D. Emslie; W.P. Patterson (July 2007). "Abrupt recent shift in δ13C and δ15N values in Adélie penguin eggshell in Antarctica". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (28): 11666–11669. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608477104. PMC 1913849

. PMID 17620620.

. PMID 17620620. - ↑ Eccleston, Paul (11 December 2007). "Penguins now threatened by global warming". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ McKie, Robin (9 June 2012). "'Sexual depravity' of penguins that Antarctic scientist dared not reveal". The Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 Russell, D. G. D.; Sladen, W. J. L.; Ainley, D. G. (2012). "Dr. George Murray Levick (1876–1956): Unpublished notes on the sexual habits of the Adélie penguin". Polar Record. 48 (4): 1. doi:10.1017/S0032247412000216.

- 1 2 3 McKie, Robin (9 June 2012). "'Sexual depravity' of penguins that Antarctic scientist dared not reveal". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ↑ "Shock at sexually 'depraved' penguins led to 100-year censorship". The Week. 10 June 2012.

- ↑ Ainley, David G. (2002). The Adélie Penguin: Bellwether of Climate Change. Columbia University Press. pp. 310 pp. with 23 illustrations, 51 figures, 48 tables, 16 plates. ISBN 0-231-12306-X.

- ↑ Lescroël, A. L.; Ballard, G.; Grémillet, D.; Authier, M.; Ainley, D. G. (2014). Descamps, Sébastien, ed. "Antarctic Climate Change: Extreme Events Disrupt Plastic Phenotypic Response in Adélie Penguins". PLoS ONE. 9 (1): e85291. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085291. PMC 3906005

. PMID 24489657.

. PMID 24489657. - ↑ Rejcek, Peter (13 August 2010). "Researchers follow Adélie penguin winter migration for the first time". The Antarctic Sun.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Janes, Donald (1997). "Osmoregulation by Adélie Penguin Chicks on the Antarctic Peninsula". The Auk. 114 (3).

- ↑ Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1980). "The Salt-Secreting Gland of Marine Birds". Circulation. 21.

- 1 2 Eckhart, Simon (1982). "The Osmoregulatory System of Birds with Salt Glands". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 71: 547–566.

- 1 2 Andrzej, Myrcha; Anderzej, Tatur (1991). "Ecological Role of the Current and Abandoned Penguin Rookeries in the Land Environment of the Maritime Antarctic". Polish Polar Research. 12 (1): 3–24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pygoscelis adeliae. |

- BirdLife species factsheet

- Adelie penguins at the Polar Conservation Organisation

- Roscoe, R. "Adelie Penguin". Photo Volcaniaca. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

_04.jpg)