Aklanon people

| |||

| Total population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (500,000-1,000,000 (est.) with Akeanon heritage) | |||

| Regions with significant populations | |||

|

Aklan Panay; Metro Manila, Mindanao, Romblon ----- ----- Worldwide | |||

| Languages | |||

| Philippine languages (Aklanon, Malaynon, Ati, Hiligaynon, Kinaray-a, Tagalog), English | |||

| Religion | |||

|

Predominantly Roman Catholicism. Also minority, Protestantism, others | |||

| Related ethnic groups | |||

| Filipinos (Ati, Karay-a, Hiligaynon, Romblomanon, Ratagnon, other Visayans), Austronesian peoples | |||

The Aklanon people are part of the wider Visayan ethnolinguistic group, who constitute the largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group.

Area

Aklanon form the majority in the province of Aklan in Panay. They are also found in other Panay provinces such as Iloilo, Antique, and Capiz, as well as Romblon. Like the other Visayans, Aklanons have also found their way to Metro Manila, Mindanao, and even the United States.

History

The Aklanons are descendants of the Austronesian-speaking immigrants who came to the Philippines during the Iron Age. They got their name from the river Akean, which means where there is boiling or frothing.

Minuro it Akean

Aklan, originally known as Minuro it Akean, is considered to be the oldest province in the country and is believed to have been established as early as 1213 by settlers from Borneo. According to the tales of the Maragtas, Aklan once enjoyed primacy among the realms carved out in Panay by the 10 Bornean datus. These datus, after fleeing the tyranny of Rajah Makatunaw of Borneo, purchased the island from the Ati King Marikudo. They then established the sakup (states) of Hamtik, Akean (which includes the Capiz area), and Irong-irong, cultivated the land, and renamed the new nation as the Confederation of Madya-as (Madjaas). The datus supposedly landed in Malandog, Hamtik, where a marker commemorates the event which is reenacted in the Binirayan (literally, "place where the boats landed") Festival.

Tradition holds that the first ruler of Aklan was Datu Dinagandan who was dethroned in 1399, by Kalantiaw. In 1433, Kalantiaw III formulated a set of laws that is known today as the Code of Kalantiaw. William Henry Scott, a well-known American historian, later debunked the Code of Kalantiaw as a fraud.[1][2] However, many Filipinos, including Aklanons and other Visayans continue to believe this legend as true.

The capital of Akean changed several times. Towards the end of the 14th century, Datu Dinagandan moved the capital from the present Batan, which was captured in 1399 by Chinese adventurers under Kalantiaw. Kalantiaw established then a dynasty but it prematurely ended when his successor, Kalantiaw III, was slain in a duel with Datu Manduyog, the legitimate successor to Datu Dinagandan. When Manduyog became the new ruler, he moved the capital back to Bakan (ancient name of Banga) in 1437. Several datus succeeded Manduyog and when Miguel Lopez de Legaspi landed in Batan in 1565, Datu Kabanyag was ruling Aklan from what is now the town of Libacao.

(These historical vignettes have no historical record as credible basis, but have been manufactured in such a way as to acquire a hint of historical veracity and reinforced among school children primarily through yearly programs or shows supposedly commemorating those historical events. Nonetheless, these vignettes have found no support among the established and respected historians of the Philippines, and are thus relegated as folklore of no historical provenance or significance.)

Spanish Era

During the Spanish era, Aklanons were generally peaceful and did not revolt against Spanish rule in the area. However, the situation changed when two Aklanons, Francisco del Castillo and Candido Iban, joined the Katipunan with the intention of regaining the independence of Aklan along with the rest of the Philippines. Both were successful in ridding the area of Spaniards.

Present

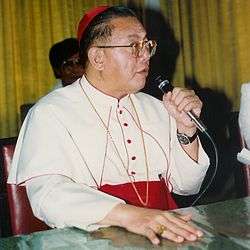

Currently, Aklanons enjoy some form of self-reliance since Aklan is now a province of the Philippines. Some Aklanons have also been active in Philippine politics, which includes Alejandro Melchor, Victorino Mapa, and Cardinal Jaime Sin, who was active in the two People Power Revolutions.

Aklanons are also known throughout the Philippines due to the location of Boracay, one of the major tourist destinations in the country.

Demographics

Aklanons number about 500,000. They are culturally close to the Karay-a and Hiligaynons. This similarity has been shown by customs, traditions, and language.

Languages

Aklanons speak the Aklan languages, which includes Aklanon and Malaynon. Ati is also spoken to some extent. Meanwhile, Hiligaynon is used as a regional language. Tagalog, Aklanon, and Hiligaynon are spoken by Aklanons in Metro Manila, while the official languages of the Philippines, Filipino and English are taught at school.

Religion

Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Aklanons likely practised the "worship" of Anitos. However, after Spanish colonization, the majority of Aklanons have become devout Roman Catholics. They are known by their devotion to the Santo Niño or Child Jesus, as shown in the Ati-atihan festival. Aklanons also practice processions during religious holidays such as the Salubong.

Culture

Most Aklanons engage in agriculture while those in the coastal areas engage in fishing. They also make handicrafts. Music, such as courtship songs or kundiman, wedding hymns, and funeral recitals, are well-developed, as it is with dance.

Historically, Aklanons practised tattooing, sometimes including henna, but abandoned the practice during the Spanish era. Recently, however, there has been a revival of it in Boracay island, which is caused primarily by its popularity with tourists.

They are among the Filipino ancestries that are tolerant to the Negritos, such as the Ati.

Literature

The Aklanons have a long tradition in literature with Marikudo as the most notable. Currently, many writers of Aklanon origin, including Melchor F. Cichon, have been trying to introduce Aklanon literature into the mainstream.

Mythology

Like other Western Visayans, Aklanons are known to believe in the aswang. Tales about these creatures are common among Aklanons and superstitions are practised to ward against the danger brought by the aswang.

See also

References

- ↑ Morrow, Paul (2003-01-30). "The Fraudulent Code of Kalantiáw". Archived from the original on 12 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- ↑ Augusto V. de Viana (2006-06-17). "http://www.manilatimes.net/national/2006/sept/17/yehey/top_stories/20060917top3.html". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10. Retrieved 2006-11-09. External link in

|title=(help)

External links

- Aklanon

- Aklanon Literature (Archived 2009-10-24)

- Precolonial Period (of the Philippines) (Archived 2009-10-24)

- BisayaExpats.com - Bisaya Expat Forum