Hex key

| Part of a series on | |

|---|---|

| Screw drive types | |

| Slot | |

| Phillips PH | |

| Pozidriv (SupaDriv) PZ | |

| Frearson | |

| Square | |

| Robertson | |

| Hex | |

| 12-point flange | |

| Hex socket (Allen) | |

| Security hex socket (pin-in-hex-socket) | |

| Torx T & TX | |

| Security Torx TR | |

| TA | |

| Tri-Wing | |

| Torq-set | |

| Spanner head (pig nose) TH | |

| Clutch A & G | |

| One-way | |

| Double-square | |

| Triple square XZN | |

| Polydrive | |

| Spline drive | |

| Double hex | |

| Bristol | |

| Pentalobe | |

A hex key (Allen key or Allen wrench) is a hexagonally shafted tool used to drive bolts and screws with corresponding sockets in their heads.

The "Allen" name is a genericization of a registered trademark of the Allen Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut, currently owned by Apex Tool Group, LLC.

Synonyms

The term "hex key" has various synonyms, which include Allen wrench, Unbrako and Inbus key or wrench. Zeta key or wrench refers to the sixth letter of the Greek alphabet, reflecting the tool's six sides.

In the fastener industry, socket head and hex socket head are used to describe the fasteners a hex key turns. The terms hex-head and hex headed are often used informally.

Features

Some characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of hex keys are:

Characteristics

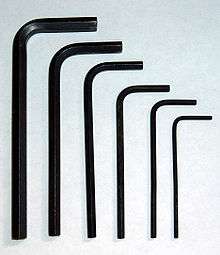

- The tool is simple, small and light

- The tool is L-shaped

- There are six contact surfaces between bolt and driver

Advantages

- The contact surfaces of the screw or bolt are protected from external damage

- The tool can be used with a headless screw

- The screw can be inserted into its hole using the key

- Torque is constrained by the length and thickness of the key

- Very small bolt heads can be accommodated

- The tool can be manufactured very cheaply, allowing inclusion with products requiring end-user assembly

- Either end of the tool can be used to take advantage of reach or torque

- The tool can be reconditioned by filing or grinding off a worn end

Disadvantages

- The hexagon is typically a smaller diameter than would be used with a corresponding external hex cap, making it more likely to round off its contact surfaces if over-torqued.

- It is much more difficult to turn a damaged (rounded or otherwise) internal fastener than an external one.

History

Available records suggest the idea of a hex socket screw drive was probably conceived between the 1860s and 1890s, but manufacture lagged until around 1910.[1] A flurry of US patents for alternative drive types were granted in this span, including those for internal-wrenching square and triangle sockets (U.S. Patent 161,390), but production of such tools and fasteners failed to materialize due to difficulties and expense of manufacture. P. L. Robertson, of Milton, Ontario, Canada, commercialized the square socket in 1908 after perfecting and patenting a cold-forming manufacturing method which used appropriate materials and correct die design.

In 1909–1910, William G. Allen patented a method of cold-forming screw heads around a hexagonal die (U.S. Patent 960,244). Advertisements published in 1910 for the "Allen safety set screw" by the Allen Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut, establish him as the hex key pioneer.[2]

In his autobiography, the founder of the Standard Pressed Steel Company (SPS; now SPS Technologies, Inc.), Howard T. Hallowell Sr, presents a version of events[3] in which SPS developed a hex socket drive in-house, independently of Allen, circa 1911. From this came the Unbrako line of products. This account from Hallowell does not mention the Allen patent of 1910, nor the Allen safety set screw product line. Hallowell does describe, however, the same inspiration also mentioned in connection with Allen for a wave of adoption of the hex socket head, beginning with set screws and followed by cap screws. This was an industrial safety campaign, part of the larger Progressive Movement, to get headless set screws onto the pulleys and shafts of the line shafting that was ubiquitous in factories of the day. The headless set screws would be less likely to catch the clothing of workers and pull them into injurious contact with the running shaft.

SPS at the time was a prominent maker of shaft hangers and collars, the latter of which were set in place with set screws. In pursuit of headless set screws with a better drive than a straight slot, Hallowell said, SPS had sourced set screws of square-socket drive from Britain, but they were very expensive.[4] (This was only 2 years after Robertson's Canadian patent.) This cost problem drove SPS to purchase its first screw machine and make its screws in-house, which soon led to SPS's foray into fastener sales (for which it later became well known within the metalworking industries). Hallowell said that "[for] a while we experimented with a screw containing a square hole like the British screw but soon found these would not be acceptable in this country [the U.S.]. Then we decided to incorporate a hexagon socket into the screw […]."[5] Hallowell does not elaborate on why SPS found that the square hole "would not be acceptable in this country", but it seems likely that it would have to have involved licensing Robertson's patent, which would have defeated SPS's purpose of driving down its cost for internal-wrenching screws (and may have been unavailable at any price, as explained at "List of screw drives > Robertson"). The story, if any, of whether SPS's methods required licensing of Allen's 1910 patent is not addressed by Hallowell's memoir. The book does not mention which method—cold forming or linear broaching—was used by SPS in these earliest years. If the latter was used, then Allen's patent would not have been relevant.

Soon after SPS had begun producing the [hex] socket head set screw, Hallowell had the idea to make a [hex] socket head cap screw (SHCS). Hallowell said, "Up to this moment none of us had ever seen a socket head cap screw, and what I am about to relate concerns what I believe was the first socket head cap screw ever made in this country [the U.S.]."[6] SPS gave their line of screws the Unbrako brand name, chosen for its echoing of the word unbreakable.

Hallowell said that acceptance of the internal-wrenching hexagon drive was slow at first (painfully slow for SPS's sales), but that it eventually caught on quite strongly.[7] This adoption occurred first in tool and die work and later in other manufacturing fields such as defense (aircraft, tanks, submarines), civilian aircraft, automobiles, bicycles, furniture and others.

Concerning the dissemination of the screws and wrenches, Hallowell said that "the transition from a square head set screw [Hallowell refers here to the then-ubiquitous external-wrenching square drive] to a hexagon socket head hollow set screw[,] for which had to be developed special keys or wrenches for tightening or loosening the screw, was the cause of more profanity among the mechanics and machine manufacturers than any other single event that happened. […] I am sure that the old-timers who read this book will remember this period vividly."[8] (These transitional growing pains echo those experienced many decades later with the adoption of the Torx drive).

World War II, with its unprecedented push for industrial production of every kind, is probably the event that first put most laypersons in contact with the internal-wrenching hexagon drive. (Popular Science magazine would note in 1946 that "Cap screws and setscrews with heads recessed to take hexagonal-bar wrenches are coming into increasing use.")[9]

It appears that the internal-wrenching hexagon drive may have been independently reinvented in various countries. At the least, the design (or methods of manufacturing it) was patented in various countries by various patentees, and its name varies. For example, in various European countries, it is known by the name Inbus (often misspelled *Imbus), after the company that patented them in Germany in 1936, Bauer und Schaurte of Neuss (Inbus stands for Innensechskantschraube Bauer und Schaurte). Similarly, there is another name in Italian (brugola), stemming from the name Officine Egidio Brugola, a company who first commercialized Allen's products in Italy.

Hex key standard sizes

Hex keys are measured across-flats (AF), which is the distance between two opposite (parallel) flat sides of the key. Standard metric sizes are defined in ISO 2936:2001 "Assembly tools for screws and nuts—Hexagon socket screw keys", also known as DIN 911, and, measured in millimeters (mm) are:

- 0.7, 0.9, 1.0, 1.25, 1.3, 1.5

- 2 to 6 in 0.5 mm increments

- M2 to M6 in 0.5 mm increments (see below for M1, M2 style designation).

- 7 to 22 in 1 mm increments

- 24, 25, 27, 30, 32, 36, 42 and 46 mm.

Metric hex wrench sizes are sometimes referred to using the designation "M" followed by the size in millimeters of the tool or socket, e.g. "M6", although this may be confused with the standard use of "M6" which refers to the size of a metric screw or bolt.

American sizes are defined in ANSI/ASME standard B18.3-1998 "Socket Cap, Shoulder, and Set Screws (Inch Series)". Values given here are taken from Machinery's Handbook, 26th Edition, section "Fasteners", chapter "Cap and Set Screws", table 4 (p. 1601).

| Screw size (nominal) | Socket size (inches) | Approximate socket size (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| No. 6 | 7/64 | 2.78 |

| No. 8 | 9/64 | 3.57 |

| No. 10 | 5/32 | 3.97 |

| 1/4 | 3/16 | 4.76 |

| 5/16 | 1/4 | 6.35 |

| 3/8 | 5/16 | 7.94 |

| 7/16 | 3/8 | 9.53 |

| 1/2 | 3/8 | 9.53 |

| 5/8 | 1/2 | 12.70 |

| 3/4 | 5/8 | 15.88 |

| 7/8 | 3/4 | 19.05 |

| 1 | 3/4 | 19.05 |

Note that numerous other sizes are defined; these are the most common.

Using a hex wrench on a socket that is too large may result in damage to the fastener or the tool. An example would be using a 5 mm tool in a 5.5 mm socket. Because hex-style hardware and tools are available in both metric and Imperial and customary sizes (the latter sometimes labelled "SAE"), it is also possible to select a tool that is too small for the fastener by using an Imperial/customary tool on a metric fastener, or the converse. There are some exceptions to that. For example, 4 mm keys are almost exactly the same size as 5/32", and 8 mm keys are almost exactly the same size as 5/16", which makes 4 mm and 8 mm preferred numbers for consumer products such as self-assembly particle-board furniture, because end users can successfully use an imperial key on a metric fastener, or vice versa, without stripping. 19 mm keys are so close to the same size as ¾" that they are completely interchangeable in practical use.

Variants

A security version of the hex head includes a pin in the center. These fasteners are said to have a "center pin reject" feature to prevent standard hex wrenches from working. A special driver must be used to fasten or remove these fasteners. The TORX head's security variant also has such a pin for the same reason.

Some hex keys have a ball on one end, which allows the tool to be used at an angle off-axis to the screw. This type of hex key was invented in 1964 by the Bondhus Corporation,[10] and is now manufactured by several other companies.

While providing access to otherwise inaccessible fasteners, thinning of the tool shaft to create the ball shape renders it weaker than the straight-shaft version, limiting the torque that can be applied. The tool also makes point contact with the fastener as opposed to the line contact seen in the straight style tools.

Manufacturing methods

- Hex socket screw heads are usually made by stamping the head with a die, plastically deforming the metal. Other ways to generate the hex socket include linear broaching and rotary broaching. Broaching the heads with a linear broach is essentially the metalworking analog of mortising wood with a mortising machine; a hole is drilled and then the corners are broached out. This operation often leaves little telltale curled chips still attached at the bottom of the socket. These are negligible for most applications.

- Hex keys are made by imparting the hexagon cross-section to steel wire (for example, with a die), then bending and shearing.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hex key. |

- ↑ Rybczynski 2000, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Alloy Artifacts, Various Tool Makers (section on Allen Manufacturing Company), retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ↑ Hallowell 1951, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Hallowell 1951, p. 51.

- ↑ Hallowell 1951, p. 52.

- ↑ Hallowell 1951, p. 57.

- ↑ Hallowell 1951, pp. 54,57–59.

- ↑ Hallowell 1951, p. 54.

- ↑ Burton 1946, p. 149.

- ↑ Premiere ball end tools, Bondhus Corporation

Bibliography

- Burton, Walter E. (February 1946), "Hold Everything", Popular Science, New York, NY, USA, 148 (2).

- Hallowell, Howard Thomas, Sr (1951), How a Farm Boy Built a Successful Corporation: An Autobiography, Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, USA: Standard Pressed Steel Company, LCCN 52001275, OCLC 521866.

- Rybczynski, Witold (2000), One good turn: a natural history of the screwdriver and the screw, Scribner, ISBN 978-0-684-86729-8, LCCN 00036988, OCLC 462234518. Various republications (paperback, e-book, braille, etc).