Allicin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

S-Prop-2-en-1-yl prop-2-ene-1-sulfinothioate | |

| Other names

2-Propene-1-sulfinothioic acid S-2-propenyl ester 3-[(Prop-2-ene-1-sulfinyl)sulfanyl]prop-1-ene S-Allyl prop-2-ene-1-sulfinothioate | |

| Identifiers | |

| 539-86-6 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image Interactive image |

| 1752823 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28411 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL359965 |

| ChemSpider | 58548 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.935 |

| EC Number | 208-727-7 |

| 2419 | |

| KEGG | C07600 |

| MeSH | Allicin |

| PubChem | 65036 |

| UNII | 3C39BY17Y6 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H10OS2 | |

| Molar mass | 162.26 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid |

| Density | 1.112 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | <25 °C |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Allicin is an organosulfur compound obtained from garlic, a species in the family Alliaceae.[1] It was first isolated and studied in the laboratory by Chester J. Cavallito and John Hays Bailey in 1944.[2][3] When fresh garlic is chopped or crushed, the enzyme alliinase converts alliin into allicin, which is responsible for the aroma of fresh garlic.[4] The allicin generated is unstable and quickly changes into a series of other sulfur-containing compounds such as diallyl disulfide.[5] Allicin is part of a defense mechanism against attacks by pests on the garlic plant.[6]

Structure and occurrence

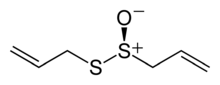

Allicin features the thiosulfinate functional group, R-S(O)-S-R. The compound is not present in garlic unless tissue damage occurs,[1] and is formed by the action of the enzyme alliinase on alliin.[1] Allicin is chiral but occurs naturally only as a racemate.[3] The racemic form can also be generated by oxidation of diallyl disulfide:[7]

- (SCH2CH=CH2)2 + RCO3H → CH2=CHCH2S(O)SCH2CH=CH2 + RCO2H

Alliinase is irreversibly deactivated below pH 3; as such, allicin is generally not produced in the body from the consumption of fresh or powdered garlic.[8][9] Furthermore, allicin can be unstable, breaking down within 16 hours at 23 °C.[10]

Biosynthesis

Allicin is an oily, slightly yellow liquid that gives garlic its unique odor. It is a thioester of sulfenic acid and is also known as allyl thiosulfinate.[11] Its biological activity can be attributed to both its antioxidant activity and its reaction with thiol-containing proteins.[12]

In the biosynthesis of allicin (thio-2-propene-1-sulfinic acid S-allyl ester), cysteine is first converted into alliin (+ S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide). The enzyme alliinase, which contains pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), cleaves alliin, generating allysulfenic acid, pyruvate, and ammonium.[12] At room temperature allysulfenic acid is unstable and highly reactive, which cause two molecules of it to spontaneously combine in a dehydration reaction to form allicin.[11]

Produced in garlic cells, allicin is released upon disruption, producing a potent characteristic scent when garlic is cut or cooked.[5][6]

Research

Allicin has been studied for its potential to treat various kinds of multiple drug resistance bacterial infections, as well as viral and fungal infections in vitro, but as of 2016, the safety and efficacy of allicin to treat infections in people was unclear.[13]

In a small clinical trial, a daily high dose of extracted allicin (20 times the amount in a garlic clove) showed effectiveness to prevent the common cold.[14] A Cochrane review found this to be not sufficient to draw conclusions.[15]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to allicin. |

- Allyl isothiocyanate, the active piquant chemical in mustard, radishes, horseradish and wasabi

- syn-Propanethial-S-oxide, the chemical found in onions

- List of phytochemicals in food

References

- 1 2 3 Eric Block (1985). "The chemistry of garlic and onions". Scientific American. 252 (March): 114–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0385-114. PMID 3975593.

- ↑ Cavallito, Chester J.; Bailey, John Hays (1944). "Allicin, the Antibacterial Principle of Allium sativum. I. Isolation, Physical Properties and Antibacterial Action". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 66 (11): 1950. doi:10.1021/ja01239a048.

- 1 2 Eric Block (2010). Garlic and Other Alliums: The Lore and the Science. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ↑ Kourounakis, PN; Rekka, EA (November 1991). "Effect on active oxygen species of alliin and Allium sativum (garlic) powder". Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 74 (2): 249–252. PMID 1667340.

- 1 2 Ilic, Dusica; Nikolic, Vesna; Nikolic, Ljubisa; Stankovic, Mihajlo; Stanojevic, Ljiljana; Cakic, Milorad (2011). "Allicin and related compounds: Biosynthesis, synthesis and pharmacological activity" (PDF). Facta Universitatis. 9 (1): 9–20. doi:10.2298/FUPCT1101009I.

- 1 2 Borlinghaus, J; Albrecht, F; Gruhlke, M. C.; Nwachukwu, I. D.; Slusarenko, A. J. (2014). "Allicin: Chemistry and biological properties". Molecules. 19 (8): 12591–618. doi:10.3390/molecules190812591. PMID 25153873.

- ↑ Cremlyn, R. J. W. (1996). An introduction to organosulfur chemistry. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-95512-4.

- ↑ Brodnitz, M.H.; Pascale, J.V.; Derslice, L.V. (1971). "Flavor components of garlic extract". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 19 (2): 273–5. doi:10.1021/jf60174a007.

- ↑ Yu, Tung-HSI; Wu, Chung-MAY (1989). "Stability of Allicin in Garlic Juice". Journal of Food Science. 54 (4): 977. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1989.tb07926.x.

- ↑ Hahn, G (1996). Koch, HP; Lawson, LD, eds. Garlic: the science and therapeutic application of Allium sativum L and related species (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins. pp. 1–24. ISBN 0-683-18147-5.

- 1 2 Nikolic, V; Stankovic, M; Nikolic, Lj; Cvetkovic, D (Jan 2004). "Mechanism and kinetics of synthesis of allicin". Pharmazie. 59 (1): 10–4. PMID 14964414.

- 1 2 Rabinkov, A; Miron, T; Konstantinovski, L; Wilchek, M; Mirelman, D; Weiner, L (Feb 1998). "The mode of action of allicin: trapping of radicals and interaction with thiol containing proteins". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1379 (2): 233–44. doi:10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00104-9. PMID 9528659.

- ↑ Marchese, Anna; Barbieri, Ramona; Sanches-Silva, Ana; Daglia, Maria; Nabavi, Seyed Fazel; Jafari, Nematollah Jonaidi; Izadi, Morteza; Ajami, Marjan; Nabavi, Seyed Mohammad (2016). "Antifungal and antibacterial activities of allicin: A review". Trends in Food Science and Technology. 52: 49. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2016.03.010.

- ↑ Nahas, R; Balla, A (January 2011). "Complementary and alternative medicine for prevention and treatment of the common cold.". Canadian Family Physician. 57 (1): 31–6. PMC 3024156

. PMID 21322286.

. PMID 21322286. - ↑ Lissiman, E; Bhasale, AL; Cohen, M (11 November 2014). "Garlic for the common cold". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (11): CD006206. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006206.pub4. PMID 25386977.

.jpg)