Alternatives to incarceration

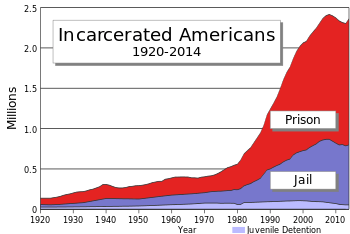

An alternative to incarceration is any kind of punishment or treatment other than time in prison or jail that can be given to a person who is convicted of committing a crime. Alternatives can take the form of capital punishment, exile, fines, restorative justice, corporal punishment, transformative justice, or the abolition of incarceration entirely. Tough sentencing laws, record numbers of drug offenders and high crime rates have contributed to the United States having the largest prison population and the highest rate of incarceration in the world, according to criminal justice experts. The United States’ prison population topped 2 million inmates for the first time in history on June 30, 2002. By this time, America’s jails held 1 in every 142 U.S. residents. Since 1997, there has been a 5.4% increase in prison inmates and the numbers will continue to rise unless alternatives to what are adopted.[1][2]

The prison abolition movement

The prison abolition movement attempts to eliminate prisons and the prison system. Prison abolitionists see the prisons as an ineffective way to decrease crime and reform criminals. They also believe the modern criminal justice system to be racist, sexist, and classist. One of the many arguments made for prison abolition is that the majority of people accused of crime cannot afford to pay a lawyer.[3] The Anarchist Black Cross was a key group involved in the prison abolition movement that still persists today. A variety of proposed alternatives to prisons arose from the prison abolition movement.

Movement for alternatives to incarceration

The prison reform and alternatives to incarceration has been largely supported by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime(UNODC). The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime promotes reform from an argumentative point of view that includes human rights considerations, imprisonment and poverty, public health consequences of imprisonment, detrimental social impacts and the cost of imprisonment. The UNODC highly encourages member nations to adopt alternatives to incarceration, dropping the traditional ways to punishment such as imprisonment and parole.

Human rights issues

Imprisonment often takes away the basic liberties of human rights as declared in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Many inmates in the U.S. prison system have voiced the inhumane conditions that they were subjected to during their time. While prisons enforce and encourage inmates to receive counselling sessions to regain their confidence and find ways to reintegrate into the society again, many inmates expressed that their hard-earned self-esteem is regularly stripped away by the prison policies. Some women prisoners have voiced that even though it seems nice to be able to leave the prison complex for a while, they would rather not leave the penal institutions complex because of the degrading strip search that awaits them upon their return. For those who have experience sexual abuse, the obligatory search brings up traumatic experiences and episodes. Similar to this example, many inmates are subjected to unfair treatments and abuse from prison guards.[4]

Financial and socioeconomic impacts

Incarceration affects the financial circumstances of families by means of taking away financial sources, thus putting the families of incarcerated into an endless cycle of poverty, marginalization and criminality. The socioeconomic situations of nations are thus greatly impacted. Mass incarceration has been found to decrease the overall economic circumstances of families. With the increase and spike of incarceration rates, many families continue to fall below the official poverty rate, thereby magnifying the hourglass economy.[5] Statistics from a study of released inmates show that populations are finding difficulty to re-integrate back into the society, and have a high rearrest rates. This is due in part from the overcrowding of jail cells and the high concentration of diseases and substance abuse. The environment that most of these inmates are exposed to is not a positive influence for motivation to change for the better.[6] Rearrest rates in addition to newly convicted individuals, add on to the burden of taxpayers.[7]

Public health consequences

Financial circumstances are not the only factor affected when one is imprisoned. Many offenders who enter prisons have existing health conditions which they hope to seek treatment for during their time served, as financial circumstances do not allow them to regularly receive medical help. However, their conditions only continue to worsen after their time at penal institutions. Due to the increased, overcrowded populations of prisons and the lack of medical personnels, many of the prisoners' conditions deteriorate. The conditions of these inmates upon release will only further worsen public health rates increasing the incidence of HIV infections, substance abuse and tuberculosis in the society.[8]

Many groups and organizations have stepped forward to push for an end to incarceration. These groups, for example, the Anarchist Black Cross have developed a strong passion to abolish the prison system completely. Research done by many professionals, particularly from that of the legal, political science and criminal justice field, have shown that Alternatives to Incarceration bring more benefits to the society in the long run as compared to imprisonment. The prison abolition movement is not only driven by the benefits that released inmates will have when re-integrating back into larger society but also through the restructuring of the economy and the activation of antiglobalization movements.[9]

Benefits of alternatives to incarceration

There are many benefits of alternatives to incarceration. These benefits can be summarized in four categories: judicial, economic, social, and safety.

All around benefits of Alternative Sentencing.

Alternative Sentencing has many benefits compared to jailing or prison. A person that is put into an Alternative Sentencing system most likely has a lesser offense than those who are sent to be imprisoned or jailed. This program allows offenders to keep a job, and still experience outside life instead of full set isolation. Without Alternative Sentencing jails would become very over crowded. These are just a few examples why Alternative Sentencing has more benefits than jailing or prisons.

Judicial benefits

In the situation where courts are unable to decide which punishment best fits a specific case, a wide array of sentencing options is the best solution. Without other options, limiting both violent and non-violent, serious and non-serious crimes to the same prison sentence will cause not only turbulence in prison, but dissatisfaction in prisoners. Limiting consequences of crime to only imprisonment may lead to oversimplification of diverse and complicated crimes, resulting in the situation above. For a court to truly be cost-effective, fair, and efficient, other options like rehabilitation may be more favorable. For example, in the case of non-violent cases where an offender has some mental health issue, a mental health court would be a better solution.[10]

Economic benefits

It is also possible for alternatives to incarceration to save money and keep government lean. Federal prison and private prison solutions to crime cost over $28,000 per year per inmate.[11] Any option that costs below this price point is a viable way to save money. In addition, cumulative costs resulting from prison overcrowding can be avoided, saving even more money. In comparison, a drug court system costs below $10,000 per year per offender.[12] Less restrictions and better costs overall will overcome the cost of offering and managing multiple options, resulting in a leaner, more efficient economic system in total. Spending the full price as an inmate on each offender is more expensive than tailoring options for each separate case.[13]

Social benefits

The majority of adults, eight out of ten, believe that alternatives to incarceration, including systems like supervised probation and community service are more appropriate sentences for nonviolent, nonserious offenders.[14] In general, the public is inclined towards being more lenient and more helpful for those that do not directly and immediately pose a threat to their communities. A majority believes using an alternative is a better option, which means that any systematic change towards that direction would be well-accepted and approved by citizens. A push for alternatives to incarceration in politics would lead to a more cohesive viewpoint between society and government policy.[15]

Safety benefits

Whereas prison does not have focused efforts designed to reform and redirect criminals towards better futures, oftentimes alternatives to incarceration do. A system like a drug court is a more reasonable way to treat certain types of offenders, ensuring that their behavior improves upon their release. Because these systems are designed specifically to reform and improve an individual's mindset, they lead to better results than a prison, which is solely designed to punish an individual's mindset, and remove them from their personal communities. This leads to a safer environment for everyone when these offenders finish their respective sentences and return to society.

Alternatives to incarceration: examples of restorative and transformative justice approaches

Addressing crimes involving sexual offenders

Although there have been changes in the way sex offenders are treated in the last twenty years, there is a need to differentiate between the different types rather than placing them in the same box. By using a compassionate approach, possible sex offenders (those addicted to pornographic images, for example) would seek help before they commit any kind of crime. Therefore, sex offending needs to be seen within a public health framework rather than a criminal justice one.[16]

Options in lieu of incarcerating mothers and parents

When it comes to incarcerating parents, each case is looked at closely in order to determine what kind of parent he/she is. Parents presenting a positive influence should go through intensive parenting and close monitoring and supervision. If a woman has young children, a shorter sentence should be given so that she can be active in her children’s lives. Meanwhile, those who negatively affect their children would go on probation by providing for their children financially (child support) while working at a different community and undergoing rehabilitation.[17]

Prison nurseries

Mothers being incarcerated are subjected to a form of alternative during their incarceration. Yet, some may view this either as an advantage in having a less intense trial or a disadvantage in having to deal with a child. Studies have provided an alternative to the relationships between children and their mothers whom are incarcerated. Along with the path of foster care, some prison complex have begun the formation of a prison nursery as an aid given to both mothers and children. Around 70% of women incarcerated have children that are minors and many of them include pregnant women.

Since incarcerated pregnant women would have to deal with the birth of a child behind bars, the prison nurseries helps mothers deal with the pregnancy, birth, and postpartum in order to keep the relationship between mothers and infants stable. The productivity of a prison nursery is having the mothers of the infant be the primary caregivers during some or all of their sentence. The attribute these nurseries bring forth is the actual physical closeness between mother and child as well as the infant being in a supportive environment rather than the dullness of prison cells. The program was established to create a positive development in the children’s lives and have mothers avoid recidivism. Some cases have shown a decrease in maternal recidivism and a growth in gender-responsive program offered by the government toward women.[18]

In the case of those opposing prison nurseries, they recognize how these women are placed in community co-residence sites instead of jail sites giving to much comfort to the inmates pregnant. Even though these women have to attend parenting programs, the objective of classes is unknown to be effective to the individuals. Many of the studies that people have seen in correlation with the nurseries have little significance on whether or not they help in a positive or negative manner toward women prisoners. One reason that has been seen as a constant issue with mothers who were sentenced to jail time is related to drug substance abuse. Dealing with drugs is more likely for the individual to be recidivated and go back to jail within three years. Yet, there is insufficient data and studies to actually clarify what would help mothers change their ways after their sentence in prison either with or without the gender response actions from the government aid.[19]

Fathers and child support

Coming from a low income household is already a struggle, as a parent the amount one pays is indefinite. Fathers who have low income and have to pay child support have a high possibility of being incarcerated. It is already a difficult task to have the basic needs, and as a father who is required to pay a certain amount each month is a huge load to carry. The law is simple. If the father does not pay for child support for either reason, the individual can be taken into custody for about six months. While these individuals are at risk of going to jail for not fulfilling their duty, their debt just piles up as they sit in jail. Their relationship with their children fades away for a while as the father becomes absent in his time behind bars. Incarceration prevents them from fulfilling their jobs not just to the economy, but as fathers as well.

Incarceration creates more debt towards the individual than aid to society. Fathers are now given a chance through programs such as the Alternatives to Incarceration(ATI) module to have chance in life rather than punishment. The ATI module attempts to give fathers preparatory skills and confidence of securing a job for themselves. Instead of wasting their times in prison cells, they are placed to work for the skills needed to obtain a job that will help them sustain the life of their children and themselves.

Incarceration for not paying child support had alternatives that did not have a positive outcome. Alternatives such as burying the fathers in debt rather than helping them find a resolution to their problem. The options contained either work release or home detention. As work release has them fulfill their time behind bars and go to work, there is only certain amount of time for the individual to do any and at times they do not have a job coming back to the main reason why they are not paying their child support. Home Detention is another way in which it alters from incarceration. Instead of being inside a prison, the prison comes to the individual at the footsteps of their homes. Fathers are being charged for monitoring expenses and have no employment during that period since they cannot leave their homes. They are not working and not able to see their children. More of a loss than a gain. At the same time, many of them are likely to have more charges as they would violate their home detention in order to seek a job or visit their children. Then they will be re-incarcerated and nothing is beneficiary to either the economy and/or individual.

Programs such as the AIT module helps low-income fathers by giving them life skills, parenting workshops communication abilities, and building healthier relationships between families. The attempt with this module is to build a support system that aids rather than wastes time such as sitting in a jail cell and increasingly in debt. ATI program has eligibility criteria as well as steps to appeal for one. They are reasonable as to give fathers a certain period of time to find a job and start paying the child support. Then there was certain criteria to be eligible to be in this program. The point of this program is to grasp individuals who actually want a chance to be a father and not go the easy way out.[20]

Alternatives for minors (under age of 18)

It is crucial to understand how alternatives to incarceration or detention for minors are developed and implemented. Investigations show that incarceration and education are closely associated. Restorative justice in the forms of boot camps and military programs adopted into public education options is starting to be considered. A variety of programs for anger management, self-esteem, etc. have been developed and those working with academics are called upon to develop such alternatives. It is shown that people in society are willing to pay for rehabilitation for juvenile offenders as opposed to other forms of punishment.[21] Kentucky has passed a bill in which the state encourages community-based treatment over detention for juveniles.[22] Some of the measures introduced early intervention process, evidence-based tools for screening and assessing juveniles, or place limits the maximum out-of-home placement.[23]

Community-based alternatives in Canada

In the Community Based Alternatives to Incarceration in Canada, Richard M. Zubrycki argues that by “the Canadian criminal justice system supporting the safe use of community alternatives (there would be a significant decrease) in the prison populations” (Zubrycki). He discusses mainly about community alternatives such as first time offenders receiving intervention that would help them not to commit the crime again. Another successful alternative is the Canadian government provides families with family group counseling; this is significant because it builds a stronger- closely connected support group that helps to decrease the chances of that person committing the crime again. Canada has also researched and tried to understand what Community Program works best for different types of crime offenders. From there research and perseverance “today their prison population is low and is dropping” (Zubrycki, Community Based Alternatives to incarceration in Canada).[24]

Considering other options for drug abusers

Despite the efforts of organization groups, such as the American Bar Association, in promoting alternatives to imprisonment, they seem to be ignored when it comes to the federal government. Some alternatives introduced in this article include confinement, community service, tracking devices, and expanded terms in halfway houses. Some other ideas include an increase in supervision for a decrease in time as an alternative to long-term imprisonment. This technically wouldn’t be an alternative to incarceration, but rather to full-term supervision. There are often cases such as with parents and drug abusers that need special attention and aren’t so easy to incarcerate. When it comes to parents, the court should determine what kind of parent the defendant is. Actions should be made based on that alone. Those addicted to drugs should be looked at carefully. For less dangerous criminals, treatment facilities should be the first option. The Residential Drug Abuse Program helps inmates addicted to drugs get released early, through the overcoming of their addiction.[25]

Community-based programs for youth as an alternative to incarcerated futures

Nancy Stein emphasizes on deinstitutionalizing young people by creating community-based alternatives. Many of these alternative programs in which Stein suggests are ones that are started by the community as they want to reduce the percentage of adolescents being institutionalized. One of the community programs is the Omega Boys Club where their goal is to build relationships with young people and help them make wise decisions in life. As a result, the Omega Boys Club has contributed in decreasing the rate of juvenile crime. This article shows that there are many people committed in lowering crime rates within their communities and will do whatever they can to help keep the future leaders of our nation out of trouble. The constant involvement with youth in these not well off communities is what John Brown Childs believes as “youth who actively work for peace and against violence as the inspiration for strategic direction and community rebirth.” Thus more community based alternatives to incarceration can help to lower the number of people in prison.[26]

Restorative justice models in Native American communities and the fight for self-determination

Native American communities, particularly reservations in the United States and Canada, have had a reputation for high crime rates. Restorative justice is an important alternative to the Prison Industrial Complex in these communities. Native Americans are largely overrepresented in Western penal systems, and are moving towards self-determination in administering restorative justice to their communities. Some alternatives that have been suggested are community-based programs, participation in Western sentencing circles, and re-institution of traditional corporal punishment. A successful example of this is the Miyo Wahkotowin Community Education Authority, which uses restorative techniques at the three Emineskin Cree nation schools it operates in Alberta, Canada. The Authority has a special Sohki program which has a coordinator work with students with “behavioral issues” rather than punish them and has had successful results.[27][28]

Education in prisons: exploring college preparatory alternatives for prisoners re-entering society

Individuals of underrepresented racial groups have a far larger representation in the prison system in the United States than the educational system. There has long been evidence of an inverse relationship between these two systems. Students and faculty at the University of Wisconsin are trying to use this to their advantage by teaching courses on convict criminology at their university and two of their local prisons: Oshkosh Correctional Facility and Taycheedah Correctional Institution. The course aims to give the prisoners proper tools to become students after leaving prison so that they have a lower chance of returning. Prisoners who took the course received a certificate of completion and were accepted into universities with financial aid included. Many are currently college students, and their acceptance letters were shown to other prisoners which encouraged them to take the course.[29]

Alternatives to incarceration in New York

New York City, the largest city in the United States, has created important alternatives to incarceration (ATI) program for its prison system. Judges have the option of sending those with misdemeanors or felonies to this program instead of giving them a prison sentence. The program has four categories: general population, substance abusers, women, and youth. The program has a 60% success rate, which is relatively high. Offenders who fail the program receive a mandatory prison sentence, which gives them good incentive to succeed. Those who don’t succeed tend to have a past with incarceration. As the biggest city in the United States, New York City is often a trendsetter for other cities. This program could be the first of many in the United States, which could help lower incarceration rates.[30]

See also

- Incarceration in the United States

- List of U.S. state prisons

- Mandatory sentencing

- Carceral state

- Retributive justice

- Corrections Corporation of America

- War on Drugs

- Homeland Security

- Private prison

- Federal Prison

References

- ↑ "Alternatives to incarceration fact sheet." Famm. Families Against Mandatory Minimums, 2010. Web. 9 Apr 2012. <http://www.famm.org/Repository/Files/Alternatives%20in%20a%20Nutshell%207.30.09%5B1%5DFINAL.pdf>

- ↑ SpearIt (2014-01-01). "Economic Interest Convergence in Downsizing Imprisonment". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Herivel, Tara; Wright, Paul (2003). Prison nation : The warehousing of America's poor. London: Taylor & Francis Books Ltd. p. 6. ISBN 0415935385.

- ↑ Springer, Cassie (Jan 31, 2000). "No Safe Heaven: Stories of Women in Prison". Berkeley Women's Law Journal. 15. ISSN 0882-4312.

- ↑ DeFina, Robert; Hannon, Lance (June 2013). "The impact of mass incarceration on poverty". Crime & Delinquency. 58 (4): 562–586. doi:10.1177/0011128708328864. ISSN 0011-1287.

- ↑ Freudenberg, Nicholas; Daniels, Jessie; Crum, Martha; Perkins, Tiffany; Richie, Beth E. "Coming Home From Jail: The Social and Health Consequences of Community Reentry for Women, Male Adolescents, and Their Families and Communities". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (10): 1725–1736. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325.

- ↑ SpearIt (2015-07-09). "Shackles Beyond the Sentence: How Legal Financial Obligations Create a Permanent Underclass". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Young, April M. W. "INCARCERATION AS A PUBLIC HEALTH CRISIS". American Journal of Public Health. 96 (4): 589–589. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.083691.

- ↑ Sudbury, Julia (9 December 2008). "Rethinking Global Justice: Black Women Resist the Transnational Prison-Industrial Complex". Souls. 10 (4): 344–360. doi:10.1080/10999940802523885.

- ↑ Woolredge, John; Jill Gordon (June 1997). "Predicting the Estimated Use of Alternatives to Incarceration". Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 13 (2): 121–142. doi:10.1007/bf02221305.

- ↑ Families Against Mandatory Minimums. "ALTERNATIVES TO INCARCERATION IN A NUTSHELL" (PDF). FAMM. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ Unze, David. "Drug courts offer offenders alternatives" (PDF). USA Today. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ SpearIt (2014-01-01). "Economic Interest Convergence in Downsizing Imprisonment". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Hartney, Christopher; Marchionna, Susan (1 June 2009). "Attitudes of US Voters toward Nonserious Offenders and Alternatives to Incarceration". National Council on Crime and Delinquency. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ Barklow, Rachel E. (May 2005). "Federalism and the Politics of Sentencing". Columbia Law Review. 105 (4): 1276–1314.

- ↑ Soothill, Keith (2010). "Sex Offender Recidivism". Crime and Justice. 39 (1): 145–211. doi:10.1086/652385. JSTOR 10.1086/652385.

- ↑ Osler, Mark (1 October 2009). "Intensive Parenting and Banishment as Sentencing: Alternatives for Defendant Parents". Federal Sentencing Reporter. 22 (1): 44–47. doi:10.1525/fsr.2009.22.1.44.

- ↑ Byrne, Mary W; Goshin, Lorie; Blanchard-Lewis, Barbara (2012). "Maternal separations during the reentry years for 100 infants raised in a prison nursery". Family Court Review. 50 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2011.01430.x. Print.

- ↑ Smith, Goshin L; Woods,Byrne M. (2009). "Converging streams of opportunity for prison nursery programs in the united states". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 48 (4): 271–295. doi:10.1080/10509670902848972. ISSN 1050-9674. Print.

- ↑ Luckey, Irene; Potts, Lisa (2011). "Alternative to incarceration for low-income non-custodial parents". Child & Family Social Work. 16 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00701.x. ISSN 1050-9674.

- ↑ Meiners, Erica R. (2011). "Ending the School-to-Prison Pipeline/Building Abolition Futures". The Urban Review. 43 (4): 547–565. doi:10.1007/s11256-011-0187-9.

- ↑ "New bill takes state juvenile justice system back to drawing board – treatment, not jail". Ky.gov. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ "SB200". Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Zubrycki, Richard M. (2002). "Community-Based Alternatives to Incarceration in Canada" (PDF). United Nations Publications. 61.

- ↑ Demleitner, Nora V. (1 October 2009). "Replacing Incarceration: The Need for Dramatic Change". Federal Sentencing Reporter. 22 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1525/fsr.2009.22.1.1.

- ↑ Stein, Nancy; Katz, S.; Madriz, E.; Shick, S. (1997). "Losing a Generation: Probing the Myths and Realities of Youth and Violence". Social Justice. 24 (4): 1–6. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Wildcat, Matthew (2011). "Restorative Justice at the Miyo Wahkotowin Community Education Authority". Alberta Law Review. 48 (4): 919–943. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Milward, David. (1 January 2008). "Not Just the Peace Pipe but also the Lance: Exploring Different Possibilities for Indigenous Control over Criminal Justice". Wicazo Sa Review. 23 (1): 97–122. doi:10.1353/wic.2008.0003.

- ↑ Richards, Stephen C.; Faggiani, D.; Roffers, J.; Hendricksen, R.; Krueger, J. (Autumn 2008). "Convict Criminology: Voices from Prison". Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts. 2 (1): 121–136. JSTOR 25595002.

- ↑ Porter, Rachel; Lee, S.; Lutz, M. (2011). "Balancing Punishment and Treatment: Alternatives to Incarceration in New York City" (PDF). Federal Sentencing Reporter. 24 (1): 26–29. doi:10.1525/fsr.2011.24.1.26. Retrieved 13 March 2012.